Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center

| Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center | |

|---|---|

| One Brooklyn Health | |

KJMC | |

| Geography | |

| Location | 585 Schenectady Avenue 11203, East Flatbush, Brooklyn, New York, United States |

| Coordinates | 40°39′32″N 73°56′00″W / 40.658777°N 73.933197°W |

| Organization | |

| Care system | Voluntary non-profit – Private |

| Funding | Not-for-profit, Government |

| Type | Teaching hospital, Community |

| Affiliated university | |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | Yes |

| Beds | 303 (Nursing Home 466) |

| Helipad | No |

| History | |

| Opened | 1925 |

| Links | |

| Website | www |

| Lists | Hospitals in New York State |

| Other links | Hospitals in Brooklyn |

Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center was a 303-bed full-service community teaching hospital with an estimated 2,100 full-time employees, located in the neighborhood of East Flatbush in Brooklyn, New York. The hospital was made up of a complex of eight conjoined buildings which are dispersed over a 366,000 square foot city block.

It is currently a member of One Brooklyn Health along with Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center and Interfaith Medical Center and joined the health system since its start in 2016.[1]

Kingsbrook provides ambulatory surgery, cardiology, critical care medicine, emergency/urgent care, gastroenterology, pulmonary, a ventilator dependent unit, wound care including hyperbaric chambers, diagnostic imaging including MRI and CT scanning, and an outpatient center.

The hospital completed a merger of Brooklyn hospitals under the banner of One Brooklyn Health System including Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center and Interfaith Medical Center with which New York State has invested nearly $700 million.[2]

Awards and Recognitions

[edit]The Kingsbrook Rehabilitation Institute is pleased to announce the accreditation of the Stroke and Cancer Rehabilitation programs by CARF (the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities). This accreditation distinguishes Kingsbrook's program as the only one of its kind on the Northeast, the 4th in USA and the 6th site worldwide. This achievement is an indicator of Kingsbrook's commitment to improving the quality of the lives of persons served. This accreditation recognizes the institute's success in delivering excellent patient-centered care that exceeds national and international standards in Stroke & Cancer Rehabilitation.

CARF International announced that Kingsbrook Rehabilitation Institute has been accredited for a period of three years for its Cancer and Stroke Rehabilitation programs. This accreditation decision represents the highest level of accreditation that can be awarded to an organization and shows the organization's substantial conformance to the CARF standards. An organization receiving a Three-Year Accreditation has put itself through a rigorous peer review process. It has demonstrated to a team of surveyors during an on-site visit its commitment to offering programs and services that are measurable, accountable, and of the highest quality.

History

[edit]

The current hospital center can trace its earliest origins to the mid-1920s, when The Daughters of Israel – Home for the Incurables, a relief organization, elected Max Blumberg, a prominent businessman, banker, and philanthropist, as their president, on January 4, 1925.[3] The organization was made up of a small group of women who had been making regular visits to Jewish patients in chronic illness wards of local hospitals, providing food and arranging special holiday services[3][4] By June 1925, Blumberg proposed the development of a facility which would house these ailing residents.[5] He and the organization recognized there was a considerable need for such a facility in Brooklyn and so decided to start an institution in which such long-term patients, who could not be cared for adequately in their homes, might get all the special care and attention they needed.[4] In May 1926, Blumberg decided to change the organization's name to The Jewish Sanitarium For Incurables in preparation for the eventual development of the hospital.[6] A series of fund-raising events which formally began on September 18, 1926, to gather $100,000 needed to finance the project began.[4][7][8][9]

Lefrak Pavilion

[edit]After a year of fund-raising the organization finally began construction on September 9, 1926. Ground-breaking ceremonies took place on Rutland Road and East 49th street which is the present day location of the hospital campus. The man of honor selected to break ground was New York State Deputy Attorney General Israel M. Lerner.[10][11] On June 27, 1927, the ceremonial first cornerstone was placed before an audience of 300 people who pledged themselves to help in the construction of the first building and marked the beginning of a reevaluated campaign to raise $250,000 for the cost of construction of the hospital.[12] By February 1928, the shell of the new five-story building which was planned to accommodate 250 beds was built, but another $50,000 was needed to finish the structural work and furnish it with equipment.[13][14][15] On October 14, 1928, a dedication ceremony was attended by 2,000 people to mark the completion of the building which today is called the Lefrak building.[16][17] The building was divided into wards containing 22 to 35 beds, with a sun porch adjacent to every ward.[18] Although the construction of the building was complete finicial setbacks prevented the admission of patients until the spring of 1929. After four months of raising money, the hospital officially opened its doors to patients on April 24, 1929.[4][18][19][20][21][22][23][24] On its opening day, fifty-two men and women were taken by automobile and wheelchair from Kings County Hospital Center[4] The hospital quickly filled to its capacity of 300 patients and decided to expand to deal with the constant pressure of new patients. In a speech given by Blumberg in a fundraising party, he said, "Our wards are always filled to capacity, we are the only institution of this kind in Brooklyn and we must expand if we are to care for the needy who come to us for aid."[25] In April 1930, a new wing containing a physiotherapy and dental laboratory was added.[26][27][28]

Max Blumberg Pavilion

[edit]Almost immediately after the Sanitarium's opening there was a continued demand to admit additional patients. This constant pressure made it necessary to consider plans on an additional building. The construction of a second Pavilion was decided upon and planned in June 1932. The structural design of the building was created by Tobias Goldstone who also designed the present day Leviton Pavilion. The initial design was a six-story building that was connected to the rear of the Lefrak building and have a 300 patient bed capacity containing wards, private rooms, reception, work rooms, clinics, and dietary kitchens. The expected date of completion was set in spring of 1933,[29] although financial setbacks halted the progress of the project, which began only in October 1933. The cornerstone of the building was placed on October 15, with 1200 prominent men and women of the borough in attendance. During the ceremony, four cornerstones were auctioned and the name Blumberg Pavilon was announced, in honor of its founder.[23][30] At its completion the building cost $250,000 to build and depended largely on public and private donated money. In addition to the 300 beds, the building contained an X-ray unit, examination and sterilization rooms, an occupational therapy division, and dental and physiotherapy units.[30]

Isidor and Lina Leviton Pavilion

[edit]

The first mention of a plan to construct a third building was announced on May 17, 1936, by Max Blumberg in a ceremonial event which dedicated a new 40 bed ward and the unveiling of a name change for the hospital. Max Blumberg said, "We will now be able to accommodate 500 patients, which is still not nearly enough to meet the needs of Brooklyn. Therefore the home has bought the property immediately adjoining its grounds at Rutland Road and East 49th street and is planning to construct a new building to produce facilities for the care of 250 crippled children."[31] Construction was initially planned in January 1937[31] but began in July of that year. The architect was Tobias Goldstone, who designed the original structure to be six stories and estimated its completion in nine months[32] at an estimated cost of $150,000.[33] Due to several factors, the building ended up costing $250,000 and was redesigned to be four stories. The money was to be raised by contributions and donations through fund raising bazaars,[34][35][36] dinners,[37][38] and other planned events.[39][40][41][42][43]

Although Blumberg's plan was to create a facility for children, it was reconsidered based on the portions of donations the hospital received for the project. It was decided that the new building was to be a home for nurses and ancillary staff. This was in part because of the financial influence the branches of the women's auxiliaries had on the hospital at the time.[44][45] The groundbreaking ceremonies were held on July 25, 1937. Blumberg did the honors by running a steam shovel into the ground.[32][46] The cornerstone ceremonies took place on June 19, 1938. One thousand people attended and a congratulatory massage was read from President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[47] On September 29, 1940, the structure was officially opened. More than 700 people gathered to celebrate the ceremonies, which were held in the main auditorium of the new building. At its completion, the building stood 4.5 stories high and contained facilities for 150 nurses and orderlies and provided 100 additional beds to patients.[48]

Shirley Joyce Katz Pavilion

[edit]

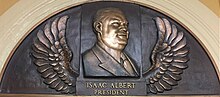

The first mention of a fourth building was on October 8, 1944. The hospital was planning its annual fundraising bazaar, which was to be held on November 21 and 22 of that year, and agreed to use the proceeds towards a $1,000,000 fund for the construction of a new building.[49] The building was initially designed to be built on land adjacent to the existing three buildings and adjoin them.[50][51][52] By December 1945, the original goal of $1,000,000 was raised to $1,500,000 due to the increase in cost of materials and labor, and a redesign was mentioned that was to add two more floors to the Anna J. Freeman Pavilion.[50] Groundbreaking ceremonies were held on June 16, 1946, and Mayor William O'Dwyer did the honors by operating a steam shovel to begin work on the building that was then mentioned to have six stories.[52][53] During the ceremonies, Isaac Albert, president of the institution at the time, stated, "Regardless of the cost of materials, we have been promised all proprieties and the help of all the contractors."[52] In October 1948, the institution's finance committee reevaluated the building's completion at a cost of $2,500,000.[54] By the fall of 1949, the building was ready for occupancy[55] and its final design was six stories, which included research laboratories, clinics, lecture halls, a hydrotherapy suit, two wings devoted to the care of children suffering from poliomyelitis and rheumatic heart conditions, and a total of 350 beds.[52] The building did not include a connection to the Anna J. Freeman Pavilion that was originally planned.

Morris and Bessie Masin Pavilion

[edit]In 1958, a four-story building named the Morris and Bessie Masin Pavilion was constructed for the purpose of researching chronic medical diseases. The construction cost of the building amounted to $2,000,000[56] An additional $1,500,000 gathered from federal government grants, various research foundations, and pharmaceutical firms was utilized for the purchase of instruments and research equipment. The institute had two electron microscopes that were capable of magnifying up to 200,000 times. The new medical research building also included administrative offices, offices for growing social service staff, a medical library, and meeting rooms for the more than thirty women's auxiliary groups which raise funds to support services to the patients. The Isaac Albert Research Institute produced 200 scientific papers.

On April 27, 1958, more than 2,500 people including political, civic, and business leaders attended the opening ceremonies.[56] Congratulatory massages came from President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Marion B. Folsom, U.S. Surgeon General Leroy Edgar Burney, New York State Governor W. Averell Harriman, and New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner.[56] Morris Masin, a member of the hospital's board of directors, in whose name and that of his late wife, Bessie, the building was named, pledged $30,000 towards the equipment fund drive, in addition to the $100,000 he had already contributed.[56] Speakers included New York City Council President Abe Stark, Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore, Deputy Commissioner of Hospitals Maurice H. Matzkin, Issac Albert, president of the hospital, and David Masin. Following the formal cutting of the ribbon, a tour of the new pavilion, which housed the Isaac Albert Research Institute, was made.[56]

Bernard and Rose Minkin Pavilion

[edit]

David Minkin spearheaded the construction of the pavilion which opened in 1967, in memory of his parents.[57]

Rutland Nursing Home/ David Minkin Rehabilitation Institute

[edit]

In August 1973, the institute began construction of a ten-floor 600-bed building to replace and add more room for long-term patients and their rehabilitation. The cost of construction was estimated to be $25,000,000.[58]

Lillian Minkin Briger‐Dr. Sigmund S. Briger Pavilion

[edit]On April 29, 1985, hospital officials unveiled a preliminary plans to construct a four-story building to meet the increasing demands on the institution.[59] The pavilion was to be a four-story building, connected to the existing Bernard and Rose Minkin Pavilion, containing 120 general and medical beds, supplementing another 20 beds for intensive care and coronary care patients.[59] An expanded medical library for advanced research was also proposed.[59] David Minkin, president at the time, named the building after his sister Mrs. Lillian Minkin Briger and her husband Dr. Sigmund S. Briger. In September 1985, the New York State Department of Health approved the project and construction then immediately began.[60] The construction of the pavilion was estimated to cost $20,000,000 (equivalent to $58,000,000 in 2024), of which $3,000,000 was donated by David Minkin.[61] The contribution was announced on his election to a 14th term as president of Kingsbrook. Over 50 years, Minkin had donated and raised millions of dollars for the institution.[61] The remaining funds for the construction and operation of the building were raised through dinners and fundraisers.[59][62] During the construction of the pavilion, the institution implemented a broader $35,000,000 capital improvement program which focused on a major overhaul to update all its facilities.[63][64] In addition to holding his presidential position, David Minkin was a philanthropist, builder, and real estate developer.[65] and had been the hospital's major benefactor to date.[65]

Name changes

[edit]The Daughters of Israel – Home for the Incurables was the organization from which the original opening hospital derived its name from. In May 1926 it was announced by Max Blumberg, the President of the organization, the hospital was to be named The Jewish Sanitarium for Incurables. The original name of the hospital represented the very nature of the patients the organization and its founder were seeking to admit. During the period of 1926 to 1936 the media outlet occasionally referred to the hospital as the Jewish Home for Incurables, and the Jewish Sanitarium for Chronics and Incurables. By the mid-1930s the hospital recognized there was no longer the need to emphasize the position as only harboring terminal and incurable patients and therefore decided to officially change its name. on May 17, 1936, the hospital changed its name to the Jewish Hospital and Sanitarium for Chronic Diseases.[31] The announcement came from Bernard Lebovitz, the Vice President at the time, during the dedication ceremonies of a new 40-bed ward.[31] In a speech addressing the name change Mr. Lebovitz stated " Only a Few years ago, hospitals and doctors were in the habit of giving up many patients and deciding that medial science could do nothing more for them, but no cases are given up as hopeless nowadays".[31] He went on to say " Patients in the Sanitarium suffer from severe cancer, paralysis, heart disease, and 45 other diseases from which patients rarely recover all live in the hope that medical science will one day discover a cure for their ailment".[31] On July 8, 1954, Isaac Albert announced that The Jewish Hospital and Sanitarium for Chronic Diseases had changed its name to Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital.[19] "This change is in keeping with the services which the institution renders. The term 'Sanitarium' connotes a rest or convalescent home or institution.".[19] By the mid-1950s the Jewish Chronic Disease hospital was an 810-bed institution dedicated to the treatment and rehabilitation patients with chronic diseases such as cancer, arthritis, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, polio, and heart conditions. It became the nation's largest voluntary, non-sectarian hospital for chronically sick and had patients ranging in age from infants to aged men and women.[19] It had facilities for occupational therapy, physiotherapy, hydrotherapy, inpatient and outpatient cerebral palsy clinics, a rheumatic fever division, cardiology division, medical research laboratories, tumor detection clinic, and other departments for the treatment and study of long-term ailments.[19] For many years, while the institution was known as the 'Home for Incurables."[19] Mr. Albert pointed out. "Today, however, the hospital is endeavoring to be an interim point between physical rehabilitation and discharge, now 'A Haven of Hope'."[19] On May 21, 1968, the hospital was renamed yet again to the current name Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center at the annual anniversary dinner for the hospital.[66] In 2010 the hospital attained corporate status effectively becoming a separate entity from the David Minkin Rehabilitation Institute/ Rutland Nursing Home. The Corporation of Kingsbrook Medical Center system to govern these bodies. This change caused Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center to go from an 864-bed facility to 326 beds splitting the remaining 538 beds to the David Minkin Rehabilitation Institute/ Rutland Nursing Home. It is of note that even though these two facilities are by definition separate they still share many services and protocols.

Services

[edit]The hospital offers several Clinical Centers:

- The Comprehensive Behavioral Health Center, comprising Inpatient Psychiatry, Geriatric Psychiatry and Outpatient Behavioral Health, specializes in the care and treatment of a variety of behavioral health issues.

- The Bone & Joint Center; offering joint replacement, sports medicine, foot/ankle and upper extremity services, treatment of hip fractures, and arthritis.

- The Neurosciences Institute; offering comprehensive care for conditions ranging from brain tumors, aneurysms, pituitary tumors, to conditions of the spine including spinal tumors, disc herniations, and spinal fractures.

- Kingsbrook Rehabilitation Institute; treating the most complicated neurological and musculo-skeletal conditions, the institute also is home to Brooklyn's only New York State approved Brain Injury & Coma Recovery Unit.

Kingsbrook's unique range of care offerings includes a long-term care division, Rutland Nursing Home. Rutland is 466-bed adult and pediatric long-term care facility that provides on-site dialysis care, ventilator dependent treatment and subacute rehab to name a few. Kingsbrook and Rutland Nursing Home are each accredited by the Joint Commission and are members of the Greater New York Hospital Association and the Healthcare Association of New York State.

The hospital is affiliated with SUNY Downstate Medical Center and serves as a training facility for a large residency training program including medical, surgery, dentistry, podiatry, and pharmacy.

Presidents in Office

[edit]Notable Research

[edit]In the 1960s, Chester M. Southam, a leading virologist and cancer researcher, conducted research on human subjects at the Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center, formerly known as the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital.[67] In this experiment, Southam, along with his colleague, Emanuel Mandel, injected HeLa cancer cells into elderly patients at the hospital without their consent.[67] Three of the hospital's doctors refused to inject the cells without the patients' consent.[68] A public suit followed in which New York State Attorney General Louis J. Lefkowitz encouraged the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York to take away Southam and Mandel's medical licenses.[69] The Board of Regents decided to suspend both of their medical licenses for a year, however, they were instead only placed on a one-year probation.[69]

References

[edit]- ^ "About OBH". Retrieved February 16, 2025.

- ^ "New Brooklyn Health system forms with 700M cash infusion". Modern Healthcare. January 25, 2018.

- ^ a b "Home For Incurables Directors Elected". The Daily Eagle. January 4, 1925.

- ^ a b c d e Levitan, Tina (April 1988). Islands of Compassion: a History of the Jewish Hospitals of New York. Olympic Marketing Corp. ISBN 9997355784.

- ^ "Raise $1,000 for Incurables". The Daily Eagle. June 6, 1925.

- ^ "Jewish Leaders Laud Blumbergs". The Daily Eagle. May 17, 1926.

- ^ "The Juive cite news". The Daily Eagle. September 5, 1926.

- ^ "$25,000 is Raised For Jewish Home As Drive Begins". The Daily Eagle. November 4, 1926.

- ^ "Plan Concert at Academy to Aid Incurables". No. February 2, 1927. The Daily Eagle.

- ^ "Lerner to Break Ground For New Incurables Home". The Daily Eagle. September 19, 1926.

- ^ "Open-Air Overture Aids Jewish Drive for Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. September 16, 1926.

- ^ "Cornerstone Laid for Jewish Home for Incurables". The Daily Eagle. June 21, 1927.

- ^ "Hospital Seeks $ 50,000". The Daily Eagle. February 19, 1928.

- ^ "$20,000 Realized to Annual Dinner for Jewish Home". The Daily Eagle. May 7, 1928.

- ^ "Annual Boat Ride Nets $1000". The Daily Eagle. July 9, 1928.

- ^ "New Hospital in Flatbush". The Daily Eagle. October 7, 1928.

- ^ "Jews Dedicate $250,000 Home For Incurables". The Daily Eagle. October 15, 1928.

- ^ a b "Jews Will Open New Sanitarium Before Passover". The Daily Eagle. February 26, 1929.

- ^ a b c d e f g "25-Year-Old Hospital Employing New Name". The Daily News. July 8, 1954.

- ^ "To Aid Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. December 9, 1928.

- ^ "Jews Further Plans to Open Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. January 22, 1929.

- ^ "Open Meeting". The Daily Eagle. April 7, 1929.

- ^ a b "To Lay Cornerstone of Jewish Hospital". The Daily Eagle. September 17, 1933.

- ^ "Jewish Sanitarium to Mark 9th Year". The Daily Eagle. March 20, 1938.

- ^ "Sanitarium Need for Funds Cited At Annual Dinner". The Daily Eagle. April 27, 1931.

- ^ "New Wing Planned By Jewish Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. February 19, 1930.

- ^ "Jewish Sanitarium Opens A New Wing This Week". The Daily Eagle. February 24, 1930.

- ^ "GetPhysio-Therapy Unit". The Daily Eagle. April 1, 1930.

- ^ "New Jewish Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. June 6, 1932.

- ^ a b "Jewish Sanitarium Cornerstone Laid: $45,000 Is pledged". The Daily Eagle. October 16, 1933.

- ^ a b c d e f "No Incurables, Declares Chief of Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. May 18, 1936.

- ^ a b "Break Ground At Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. July 26, 1937.

- ^ "Leaders in Jewish Hospital Dinner". The Daily Eagle. December 13, 1936.

- ^ "Bazaar to Aid Fund for Boro Hospital Wing". The Daily Eagle. October 15, 1939.

- ^ "Jews Set $20,000 As Goal of Bazaar". The Daily Eagle. November 12, 1939.

- ^ "Net $20,000 Goal To Aid Hospital". The Daily Eagle. November 15, 1939.

- ^ "Dinner to Benefit Boro Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. April 14, 1940.

- ^ "1,200 Expected A Dinner-Dance for Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. May 3, 1940.

- ^ "Hospital Seeks Funds for Wing". The Daily Eagle. August 9, 1937.

- ^ "Annual Luncheon". November 28, 1937.

- ^ "Jewish Hospital Dance Saturday". The Daily Eagle. December 8, 1937.

- ^ "Jewish Sanitarium Plans $25 Dinner". The Daily Eagle. April 9, 1939.

- ^ "Install Sanitarium Officers Thursday". The Daily Eagle. April 16, 1939.

- ^ "Hospital Wing Is Planned for Polio Victims". The Daily Eagle. January 11, 1937.

- ^ "Paralysis Wing Plan Denied By Hospital Board". The Daily Eagle. January 13, 1937.

- ^ "To Break Ground for Hospital Wing". The Daily Eagle. July 22, 1937.

- ^ "Hospital Wing Cornerstone Is Set in Flatbush". The Daily Eagle. June 20, 1938.

- ^ "$300,000 Wing of Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. September 30, 1940.

- ^ "Jewish Group Plans Bazaar". The Daily Eagle. October 8, 1944.

- ^ a b "Aids Appointed to Raise Funds For Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. December 14, 1945.

- ^ "2-Day Bazaar Will Aid Jewish Sanitarium". The Daily Eagle. November 11, 1944.

- ^ a b c d "Jewish Hospital Ground-Breaking Symbol of World Hope to Mayor". The Daily Eagle. June 17, 1946.

- ^ "Jewish Hospital Annex Work to Begin June 16". The Daily Eagle. May 6, 1946.

- ^ "I. Albert, Friend of The Sick, Has Need for $500,000". The Daily Eagle. October 10, 1948.

- ^ "Jewish Sanitarium to Note 24th Year A Dinner May 8". The Daily Eagle. May 10, 1949.

- ^ a b c d e "Open Hospital Pavilion". The Daily News. April 28, 1958.

- ^ Farrell, Bill (June 29, 1989). "Kingsbrook Jewish Begins a $25M Building". Daily News.

- ^ Wetherington, Roger (August 12, 1973). "Long-Term Growth for Long Term Care". The Daily News.

- ^ a b c d "Growing health needs spawn plan for building". The Daily News. April 29, 1985.

- ^ "State approves new $20M building for Crown Heights medical center". The Daily News. September 4, 1985.

- ^ a b Seaton, Charles (November 22, 1985). "Kingsbrook Med gets $3M gift". The Daily news.

- ^ "Dinner at Kingsbrook". The Daily News. August 16, 1987.

- ^ "East Flatbush Event To Help Hospital Expand". Newsday. September 19, 1988.

- ^ McKenna, Sheila (September 23, 1987). "Brooklyn Profile". Newsday.

- ^ a b "At med center". Daily News. December 10, 1987.

- ^ "1,200 to Attend Hospital Fete". The Daily News. May 16, 1968.

- ^ a b Skloot, Rebecca (2010). The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Broadway Paperbacks. p. 130.

- ^ Skloot, Rebecca (2010). The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Broadway Paperbacks. p. 132.

- ^ a b Skloot, Rebecca (2010). The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Broadway Paperbacks. pp. 134–135.