Louisville in the American Civil War

Louisville in the American Civil War was a major stronghold of Union forces, which kept Kentucky firmly in the Union. It was the center of planning, supplies, recruiting and transportation for numerous campaigns, especially in the Western Theater. By the end of the war, Louisville had not been attacked once, although skirmishes and battles, including the battles of Perryville and Corydon, Indiana, took place nearby.

Pre-war developments (1850–1860)

[edit]During the 1850s, Louisville became a vibrant and wealthy city, but together with the success, the city also harbored racial and ethnic tensions. It attracted numerous immigrants from Europe such as Irish and Germans, had a large slave market from which enslaved African Americans were sold to the Deep South, and had both slaveholders and abolitionists as residents. By 1850, Louisville became the tenth-largest city in the United States. Louisville's population rose from 10,000 in 1830 to 43,000 in 1850. It became an important tobacco market and pork packing center. By 1850, Louisville's wholesale trade totaled US$20 million in sales. The Louisville–New Orleans river route held top rank in freight and passenger traffic on the entire Western river system.[1]

Not only did Louisville profit from the river, but in August 1855, its citizens greeted the arrival of the locomotive "Hart County" at Ninth and Broadway and connection to the nation via railroad. The first passengers arrived by train on the Louisville and Frankfort Railroad. James Guthrie, president of the Louisville & Frankfort, pushed the railroad along the Shelbyville turnpike (Frankfort Avenue) through Gilman's Point (St. Matthews) and on to Frankfort. The track entered Louisville on Jefferson Street and ended at Brook Street. The state paid tribute to James Guthrie by naming the small railroad community of Guthrie, Kentucky, in Todd County after him.

Leven Shreve, a Louisville civic leader, became the first president of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N), which was to prove more important for trade. It led to the developing western states and linked with Mississippi River traffic. With the railroads, Louisville could manufacture furniture and other goods, and export products to Southern cities. Louisville was on her way to becoming an industrial city. The Louisville Rolling Mill built girders and rails, and other factories made cotton machinery, which was sold to Southern customers. Louisville built steamboats. Louisville emerged with an iron-working industry; the plant at Tenth and Main was called Ainslie, Cochran, and Company.

Louisville also became a meat packing city, becoming the second largest city in the nation to pack pork, butchering an average of 300,000 hogs a year. Louisville led the nation in hemp manufacturing and cotton bagging. Farmington Plantation, owned by John Speed, was one of the larger hemp plantations in Louisville. Hemp was Kentucky's leading agricultural product from 1840 to 1860, and the leading commodity crop of the fertile Bluegrass Region. Jefferson County led all other markets in gardening and orchards. The sales of livestock, quality horses and cattle, was also important.

Attracted by jobs and pushed by political unrest and famine, European immigrants flowed into the city from Germany and Ireland; most of them were Catholic, unlike the Protestants who lived in the city. By 1850, 359,980 immigrants arrived in the United States; by 1854, 427,833 immigrants arrived to seek a new living. With the increase in new immigrants in the city, native Louisville residents felt threatened by change, and began to express anti-foreign, anti-Catholic sentiments. In 1841, the growth in population prompted the Catholic archdiocese to move the bishop's seat from Bardstown to Louisville. The archdiocese began construction on a new Catholic cathedral, which was completed in 1852. This asserted Catholic presence in the city.

In 1843, a new political party arose, called the American Republican Party. On July 5, 1845, the American Republican party changed their name to the Native American Party and held their first national convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The party opposed liberal immigration policies. On June 17, 1854, the Order of the Star Spangled Banner held its second national convention in New York City. The members were "native Americans" and anti-Catholic. When the members answered questions about the group, they responded with "I know nothing about it," giving rise to the nickname Know-Nothing for the Native American Party. The new political party gained national support. The Know-Nothing party encouraged and tapped into the nation's prejudice and fears that Catholic immigrants would take control of the United States. Hostility to Catholics had a long history based on national rivalries in Europe. By 1854, the Know-Nothings gained control of Jefferson County's government.

Ethnic tension came to a boil in 1855, during the mayor's office election. On August 6, 1855, "Bloody Monday" erupted, in which Protestant mobs bullied immigrants away from the polls and began rioting in Irish and German neighborhoods. Protestant mobs attacked and killed at least twenty-two people. The rioting began at Shelby and Green Street (Liberty) and progressed through the city's East End. After burning houses on Shelby Street, the mob headed for William Ambruster's brewery in the triangle between Baxter Avenue and Liberty Street. They set the place ablaze and ten Germans died in the fire. When the mob burned Quinn's Irish Row on the North side of Main between Eleventh and Twelfth Streets, some tenants died in the fire; the mob shot and killed others. The Know-Nothing party won the election in Louisville and many other Kentucky counties.

As in other cities, slavery was a consuming topic; some of Louisville's economy was built on its thriving slave market. Slave traders' revenues, and those from feeding, clothing and transporting the slaves to the Deep South, all contributed to the city's economy. The direct use of slaves as labor in the central Kentucky economy had lessened by 1850. But throughout the 1850s, the state slaveholders sold 2500–4000 slaves annually downriver to the Deep South. Slave pens were located on Second between Market and Main Streets.

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 added to the controversy, as it threatened potentially lucrative expansion of slavery to western states. Louisville also had a free black population, among whom some managed to acquire property. Washington Spradling, freed from slavery in 1814, became a barber. By the 1850s, he owned real estate valued at $30,000. With its agriculture, shipping trade and industry, and slave markets, Louisville was a city that shared in cultures of both the agricultural South and the industrial North.

The eve of war (1860)

[edit]In the November 1860 Presidential election, Kentucky voters gave native Kentuckian Abraham Lincoln less than one percent of the vote. Kentuckians did not like Lincoln, because he stood for the eradication of slavery and his Republican Party aligned itself with the North. But, neither did they vote for native son John C. Breckinridge and his Southern Democratic Party, generally regarded as secessionists. In 1860, people in the state held 225,000 slaves, with Louisville's slaves comprising 7.5 percent of the population. The voters wanted both to keep slavery and stay in the Union.

Most Kentuckians, including residents of Louisville, voted for John Bell of Tennessee, of the Constitutional Union Party. It stood for preserving the Union and keeping the status quo on slavery. Others voted for Stephen Douglas of Illinois, who ran for the Democratic Party ticket. Louisville cast 3,823 votes for John Bell. Douglas received 2,633 votes.

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina seceded from the Union, and ten other Southern states followed. Kentucky, however, chose to remain neutral and later went with the Union.

War breaks out (1861)

[edit]

On April 12, 1861, Confederate Brigadier General Pierre G. T. Beauregard ordered the firing on Fort Sumter, located in the Charleston harbor, thus starting the Civil War. At the time of the Battle of Fort Sumter, the fort's commander was Union Major Robert Anderson of Louisville.

After the attack on Fort Sumter, President of the United States Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers. Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin refused to send any men to act against the Southern states, and both Unionists and secessionists supported his position. On April 17, 1861, Louisville hoped to remain neutral and spent $50,000 for the defense of the city, naming Lovell Rousseau as brigadier general. Rousseau formed the Home Guard. When Unionists asked Lincoln for help, he secretly sent arms to the Home Guard. The U. S. government sent a shipment of weapons to Louisville and kept the rifles hidden in the basement of the Jefferson County Courthouse.

Louisville residents were divided as to which side they should support. Economic interests and previous relationships often determined alliances. Prominent Louisville attorney James Speed, brother of Lincoln's close friend Joshua Fry Speed, strongly advocated keeping the state in the Union. Louisville Main Street wholesale merchants, who had extensive trade with the South, often supported the Confederacy. Blue-collar workers, small retailers, and professional men, such as lawyers, supported the Union. On April 20, two companies of Confederate volunteers left by steamboat for New Orleans, and five days later, three more companies departed for Nashville on the L & N Railroad. Union recruiters raised troops at Eighth and Main, and the Union recruits left for Indiana to join other Union regiments.

On May 20, 1861, Kentucky declared its neutrality. An important state geographically, Kentucky had the Ohio River as a natural barrier. Kentucky's natural resources, manpower, and the L&N Railroad made both the North and South respect Kentucky's neutrality. President Lincoln and Confederate President Jefferson Davis both maintained hands-off policies when dealing with Kentucky, hoping not to push the state into one camp or the other. From the L&N depot on Ninth and Broadway in Louisville and the steamboats at Louisville wharfs, supporters of the Confederacy sent uniforms, lead, bacon, coffee and war material south. Although Lincoln did not want to upset Kentucky's neutrality, on July 10, 1861, a federal judge in Louisville ruled that the United States government had the right to stop shipments of goods from going south over the L&N railroad.

On July 15, 1861, the War Department authorized United States Navy Lieutenant William "Bull" Nelson to establish a training camp and organize a brigade of infantry. Nelson commissioned William J. Landram, a colonel of cavalry; and Theophilus T. Garrard, Thomas E. Bramlette, and Speed S. Fry colonels of infantry. Landram turned his commission over to Lieutenant Colonel Frank Wolford. When Garrard, Bramlette, and Fry established their camps at Camp Dick Robinson in Garrard County, and Wolford erected his camp near Harrodsburg, Kentucky's neutrality effectively ended.[2] Brigadier General Rousseau established a Union training camp opposite Louisville in Jeffersonville, Indiana, naming the camp after Joseph Holt. Governor Magoffin protested to Lincoln about the Union camps, but he ignored Magoffin, stating that the will of the people wanted the camps to remain in Kentucky.[3]

In August 1861, Kentucky held elections for the State General Assembly, and Unionists won majorities in both houses. Residents of Louisville continued to be divided on the issue of which side to join. The Louisville Courier was very much pro-Confederate, while the Louisville Journal was pro-Union.

On September 4, 1861, Confederate General Leonidas Polk, outraged by Union intrusions in the state, invaded Columbus, Kentucky. As a result of the Confederate invasion, Union General Ulysses S. Grant entered Paducah, Kentucky. Jefferson Davis allowed Confederate troops to stay in Kentucky. General Albert Sidney Johnston, commander of all Confederate forces in the West, sent General Simon Bolivar Buckner of Kentucky to invade Bowling Green, Kentucky. Union forces in Kentucky saw Buckner's move toward Bowling Green as the beginning of a massive attack on Louisville. With twenty thousand troops, Johnston established a defensive line stretching from Columbus in western Kentucky to the Cumberland Gap, controlled by Confederate General Felix Zollicoffer.

On September 7, the Kentucky State legislature, angered by the Confederate invasion, ordered the Union flag to be raised over the state capitol in Frankfort and declared its allegiance with the Union. The legislature also passed the "Non-Partisan Act", which stated that "any person or any person's family that joins or aids the so-called Confederate Army was no longer a citizen of the Commonwealth."[4] The legislature denied any member of the Confederacy the right to land, titles or money held in Kentucky or the right to legal redress for action taken against them.

With Confederate troops in Bowling Green, Union General Robert Anderson moved his headquarters to Louisville. Union General George McClellan appointed Anderson as military commander for the District of Kentucky on June 4, 1861. On September 9, the Kentucky legislature asked Anderson to be made commander of the Federal military force in Kentucky. The Union army accepted the Louisville Legion at Camp Joe Holt in Indiana into the regular army. Louisville mayor John M. Delph sent two thousand men to build defenses around the city.

On October 8, Anderson stepped down as commander of the Department of the Cumberland and Union General William Tecumseh Sherman took charge of the Home Guard. Lovell Rousseau sent the Louisville Legion along with another two thousand men across the river to protect the city. Sherman wrote to his superiors that he needed 200,000 men to take care of Johnston's Confederates. The Louisville Legion and the Home Guard marched out to meet Buckner's forces, but Buckner did not approach Louisville. Buckner's men destroyed the bridge over the Rolling Fork River in Lebanon Junction and with the mission completed, Buckner's men returned to Bowling Green.

Louisville became a staging ground for Union troops heading south. Union troops flowed into Louisville from Ohio, Indiana, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. White tents and training grounds sprang up at the Oakland track, Old Louisville and Portland. Camps were also established at Eighteenth and Broadway, and along the Frankfort and Bardstown turnpikes.

Louisville under threats of attack (1862–63)

[edit]

By early 1862, Louisville had 80,000 Union troops throughout the city. With so many troops, entrepreneurs set up gambling establishments along the north side of Jefferson from 4th to 5th Street, extending around the corner from 5th to Market, then continuing on the south side of Market back to 4th Street. Photography studios and military goods shops, such as Fletcher & Bennett on Main Street, catered to the Union officers and soldiers. Also capitalizing on the troops, brothels were quickly opened around the city.

In January 1862, Union General George Thomas defeated Confederate General Felix Zollicoffer at the Battle of Mill Springs, Kentucky. In February 1862, Union General Ulysses Grant and Admiral Andrew Foote's gunboats captured Fort Henry and Fort Donelson on the Kentucky and Tennessee border. Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston's defensive line in Kentucky crumbled rapidly. Johnston had no choice but to fall back to Nashville. No defensive preparations had been made at Nashville, so Johnson continued to fall back to Corinth, Mississippi.

Although the threat of invasion by Confederates subsided, Louisville remained a staging area for Union supplies and troops heading south. By May 1862, the steamboats arrived and departed at the wharf in Louisville with their cargoes. Military contractors in Louisville provided the Union army with two hundred head of cattle each day, and the pork packers provided thousands of hogs daily. Trains departed for the south along the L&N railroad.

In July 1862, Confederate generals Braxton Bragg, commander of the Army of Mississippi, and Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Army of East Tennessee, planned an invasion of Kentucky. On August 13, Smith marched with 9,000 men out of Knoxville toward western Kentucky and arrived in Barbourville. On August 20, Smith announced that he would take Lexington. On August 28, Bragg's army moved west. At the Battle of Richmond, Kentucky, on August 30, Smith's Confederate forces defeated Union General William "Bull" Nelson's troops, capturing the entire force. This left Kentucky with no Union support. Nelson managed to escape back to Louisville. Smith marched into Lexington and sent a Confederate cavalry force to take Frankfort: Kentucky's capitol.

Union General Don Carlos Buell's army withdrew from Alabama and headed back to Kentucky. Union General Henry Halleck, commander of all Union forces in the West, sent two divisions from General Ulysses Grant's army, stationed in Mississippi, to Buell. Confederate General John Hunt Morgan, of Lexington, Kentucky, managed to destroy the L&N railroad tunnel at Gallatin, Tennessee, cutting off all supplies to Buell's Union army. On September 5, Buell reached Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and headed for Nashville. On September 14, Bragg reached Glasgow, Kentucky. On that same day, Buell reached Bowling Green, Kentucky.

Bragg decided to take Louisville. One of the major objectives of the Confederate campaign in Kentucky was to seize the Louisville and Portland Canal and sever Union supply routes on the Ohio River. One Confederate officer suggested destroying the Louisville canal so completely that "future travelers would hardly know where it was." On September 16, Bragg's army reached Munfordville, Kentucky. Col. James Chalmers attacked the Federal garrison at Munfordville, but Bragg had to bail him out. Bragg arrived at Munfordville with his entire force, and the Union force soon surrendered.

Buell left Bowling Green and headed for Louisville. Fearing that Buell would not arrive in Louisville to prevent Bragg's army from capturing the city, Union General William "Bull" Nelson ordered the construction of a hasty defensive line around the city. He also ordered the placement of pontoon bridges across the Ohio to facilitate the evacuation of the city or to receive reinforcements from Indiana. Two pontoon bridges built of coal barges were erected, one at the location of the Big Four Bridge, and the other from Portland to New Albany. The Union Army arrived in time to prevent the Confederate seizure of the city. On September 25, Buell's tired and hungry men arrived in the city.

Bragg moved his army to Bardstown but did not take Louisville. Bragg urged General Smith to join his forces to take Louisville, but Smith told him to take Louisville on his own.

With the Confederate army under Bragg preparing to attack Louisville, the citizens of Louisville panicked. On September 22, 1862, General Nelson issued an evacuation order: "The women and children of this city will prepare to leave the city without delay." He ordered the Jeffersonville ferry to be used for military purposes only. Private vehicles were not allowed to go aboard the ferry boats without a special permit. Hundreds of Louisville residents gathered at the wharf for boats to New Albany or Jeffersonville. With Frankfort in Confederate hands for about a month, Governor Magoffin maintained his office in Louisville and the state legislature held their sessions in the Jefferson County Courthouse. Troops, volunteers and impressed labor worked around the clock to build a ring of breastworks and entrenchments around the city. New Union regiments flowed into the city. General William "Bull" Nelson took charge of the defense of Louisville. He sent Union troops to build pontoon bridges at Jeffersonville and New Albany to speed up the arrival of reinforcements, supplies and, if needed, the emergency evacuation of the city.

Instead of taking Louisville, Bragg left Bardstown to install Confederate Governor Richard Hawes at Frankfort. On September 26, five hundred Confederate cavalrymen rode into the area of Eighteenth and Oak, capturing fifty Union soldiers. Confederates placed pickets around Middletown on the 26th, and on the 27th their soldiers repelled Union forces from Middletown near Shelbyville Pike.[5] Southern forces reached two miles from the city, but were not numerous enough to invade it. On September 30, Confederate and Union pickets fought at Gilman's Point in St. Matthews and pushed the Confederates back through Middletown to Floyd's Fork.[6]

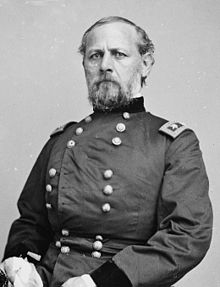

The War Department ordered "Bull" Nelson to command the newly formed Army of the Ohio. When Louisville prepared for the Confederate army under Bragg, General Jefferson C. Davis (not to be confused with Confederate President Jefferson Davis), who could not reach his command under General Don Carlos Buell, met with General Nelson to offer his services. General Nelson gave him the command of the city militia. General Davis opened an office and assisted organizing the city militia. On Wednesday, General Davis visited General Nelson in his room at the Galt House. General Davis told General Nelson that his brigade he assigned Davis was ready for service and asked if he could obtain arms for them. This led to an argument in which Nelson threatened Davis with arrest. General Davis left the room, and, in order to avoid arrest, crossed over the river to Jeffersonville, where he remained until the next day, when General Stephen G. Burbridge joined him. General Burbridge had also been relieved of command by General Nelson for a trivial cause. General Davis went to Cincinnati with General Burbridge and reported to General Wright, who ordered General Davis to return to Louisville and report to General Buell, and General Burbridge to remain in Cincinnati.

General Davis returned to Louisville and reported to Buell. When General Davis saw General Nelson in the main hall of the Galt House, fronting the office, he asked the Governor of Indiana, Oliver Morton to witness the conversation between him and General Nelson. The Governor agreed and the two walked up to General Nelson. General Davis confronted General Nelson and told him that he took advantage of his authority. Their argument escalated and Nelson slapped Davis in the face, challenging him to a duel. In three minutes, Davis returned, with a pistol he had borrowed, and shot and killed Nelson. The General whispered: "It's all over," and died fifteen minutes later.[7]

With General Nelson dead, the command switched over to General Don Carlos Buell. On October 1, the Union army marched out of Louisville with sixty thousand men. Buell sent a small Federal force to Frankfort to deceive Bragg as to the exact direction and location of the Federal army. The ruse worked. On October 4, the small Federal force attacked Frankfort and Bragg left the city and headed back for Bardstown, thinking the entire Federal force was headed for Frankfort. Bragg decided that all Confederate forces should concentrate at Harrodsburg, Kentucky, ten miles (16 km) northwest of Danville. On October 8, 1862, Buell and Bragg fought at Perryville, Kentucky. Bragg's 16,000 men attacked Buell's 60,000 men. Federal forces suffered 845 dead, 2,851 wounded and 515 missing, while the Confederate toll was 3,396. Although Bragg won the Battle of Perryville tactically, he wisely decided to pull out of Perryville and link up with Smith. Once Smith and Bragg joined forces, Bragg decided to leave Kentucky and head for Tennessee.

After the battle, thousands of wounded men flooded into Louisville. Hospitals were set up in public schools, homes, factories and churches. The Fifth Ward School, built at 5th and York Streets in 1855, became Military Hospital Number Eight. The United States Marine Hospital also became a hospital for the wounded Union soldiers from the battle of Perryville. Constructed between 1845 and 1852, the three-story Greek revival style Louisville Marine Hospital contained one hundred beds. It became the prototype for seven U.S. Marine Hospital Service buildings, including Paducah, Kentucky, which later became Fort Anderson. Union surgeons erected the Brown General Hospital, located near the Belknap campus of the University of Louisville, and other hospitals were erected at Jeffersonville and New Albany, Indiana. By early 1863, the War Department and the U.S. Sanitary Commission erected nineteen hospitals. By early June 1863, 930 deaths had been recorded in the Louisville hospitals. Cave Hill Cemetery set aside plots for the Union dead.

Louisville also had to contend with Confederate prisoners. Located at the corner of Green Street and 5th Street, the Union Army Prison, also called the "Louisville Military Prison", took over the old "Medical College building." Union authorities moved the prison near the corner of 10th and Broadway Streets. By August 27, 1862, Confederate prisoners of war were taken to the new military prison. The old facility continued to house new companies of Provost Guards. From October 1, 1862, to December 14, 1862, the new Louisville Military Prison housed 3,504 prisoners. In December 1863, the prison held over 2,000 men, including political prisoners, Union deserters, and Confederate prisoners of war.

Made of wood, the prison covered an entire city block, stretching from east to west between 10th and 11th Streets and north to south between Magazine and Broadway Streets. Its main entrance was located on Broadway near 10th Street. A high fence surrounded the prison with at least two prison barracks. The prison hospital was attached to the prison and consisted of two barracks on the south and west sides of the square with forty beds in each building. The Union commander at the Louisville Military Prison was Colonel Dent. In April 1863, Captain Stephen E. Jones succeeded him. In October 1863, military authorities replaced Captain Jones with C. B. Pratt.[8]

A block away, Union authorities took over a large house on Broadway between 12th and 13th Streets and converted it into a military prison for women.

Emancipation Proclamation

[edit]On September 22, 1862, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that as of January 1, 1863, all slaves in the rebellion states would be free. Although this did not affect slaveholding in Kentucky at the time, owners felt threatened. Some Kentucky Union soldiers, including Colonel Frank Wolford of the 1st Kentucky Cavalry, quit the army in protest of freeing the slaves. The proclamation presaged an end to slavery.

So many slaves arrived at the Union camp that the Army set up a contraband camp to accommodate them. The Reverend Thomas James, an African Methodist Episcopal minister from New York, supervised activities at the camp and set up a church and school for the refugees. Both adults and children started learning to read. Under direction by generals Stephen G. Burbridge and John M. Palmer, James monitored conditions at prisons and could call on US troops to protect slaves from being held illegally, which he did several times.[9]

The Union's recruitment of slaves into the army (which gained them freedom) turned some slaveholders in Kentucky against the US government. In later years, the depredations of guerrilla warfare in the state, together with Union measures to try to suppress it, and the excesses of General Burbridge as military governor of Kentucky, were probably more significant in alienating more citizens. Civic rights were overridden during the crisis. These issues turned many against the Republican administration.

After the war ended, the Democrats regained power in central and western Kentucky, which the former slaveholders and their culture dominated. Because this area was the more populous and the Democrats also passed legislation essentially disfranchising freedmen, the white Democrats controlled politics in the state and sent mostly their representatives to Congress for a century.[10] In the mid-1960s, the federal Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act ended legal segregation of public facilities and protected voting rights of minorities.

The Taylor Barracks at Third and Oak in Louisville recruited black soldiers for the United States Colored Troops. Slaves gained freedom in exchange for service to the Union. Slave women married to USCT men received freedom, as well. To secure legal freedom for the many slave women arriving alone at the contraband camp, Burbridge directed James to marry them to available USCT soldiers, if both parties were willing.[9] Black Union soldiers who died in service were buried in Louisville's Eastern Cemetery.

In the Summer of 1863, Confederate John Hunt Morgan violated orders and led his famous raid into Ohio and Indiana to give the northern states a taste of the war. He traveled with his troops through north-central Kentucky, trekking from Bardstown to Garnettsville, a now defunct town in Otter Creek Park. They took the Lebanon garrison, capturing hundreds of Union soldiers and then releasing them on parole. Before crossing the Ohio River into Indiana, Morgan and his crew arrived in Brandenburg, where they proceeded to capture two steamers, the John B. McCombs and the Alice Dean; the Alice Dean burned after their crossing.

After the fall of New Orleans and the capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi, on July 4, 1863, the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers were open to Union boats without harassment. On December 24, 1863, a steamboat from New Orleans reached Louisville.

In late 1863, General Hugh Ewing, brother-in-law to General Sherman, was appointed Military Commander of Louisville.

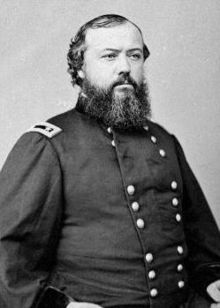

Military rule (1864)

[edit]Widespread guerrilla warfare in the state meant a widespread breakdown in the society, causing residents to suffer. In Kentucky, the Union defined a guerrilla as any member of the Confederate army who destroyed supplies, equipment or money. On January 12, 1864, Union General Stephen G. Burbridge, formerly supervising Louisville, succeeded General Jeremiah Boyle as Military Commander of Kentucky.

On February 4, 1864, at the Galt House, Union generals Ulysses S. Grant, William S. Rosecrans, George Stoneman, Thomas L. Crittenden, James S. Wadsworth, David Hunter, John Schofield, Alexander McCook, Robert Allen, George Thomas, Stephen Burbridge and Read Admiral David Porter met to discuss the most important campaign of the war. It would divide the Confederacy into three parts. In a follow-up meeting on March 19, generals Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman met at the Galt House to plan the Spring campaign. (As of 2014[update], that these meetings actually occurred has fallen into dispute.[11]) Grant took on Confederate General Robert E. Lee at Richmond and Sherman confronted General Joseph E. Johnston, capturing Atlanta, Georgia, in the process.[12]

On February 21, 1864, Jefferson General Hospital, the third-largest hospital during the Civil War, was established across the Ohio River at Port Fulton, Indiana, to tend to soldiers injured due to the war.

On July 5, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln temporarily suspended the writ of habeas corpus, which meant a person could be imprisoned without trial, his house searched without warrant, and the individual arrested without charge. Lincoln also declared martial law in Kentucky, which meant that military authorities had the ultimate rule. Civilians accused of crimes would be tried not in a civilian court, but instead a military court, in which the citizen's rights were not held as under the Constitution. On the same day, General Burbridge was appointed military governor of Kentucky with absolute authority.[13]

On July 16, 1864, Burbridge issued Order No. 59: "Whenever an unarmed Union citizen is murdered, four guerrillas will be selected from the prison and publicly shot to death at the most convenient place near the scene of the outrages."[14] On August 7, Burbridge issued Order No. 240 in which Kentucky became a military district under his direct command. Burbridge could seize property without trial from persons he deemed disloyal. He could also execute suspects without trial or question.

During the months of July and August, Burbridge initiated building more fortifications in Kentucky, although Sherman's march through Georgia effectively reduced the Confederate threat to Kentucky. Burbridge received permission from Union General John Schofield to build fortifications in Mount Sterling, Lexington, Frankfort and Louisville. Each location was to have a small enclosed field work of about two hundred yards along the interior crest, except for Louisville, which would be five hundred yards. Other earthworks were planned to follow in Louisville. All the works were to be built by soldiers, except at Frankfort, where the state would assign workers, and at Louisville, where the city would manage it. Lt. Colonel. J. H, Simpson, of the Federal Engineers, furnished the plans and engineering force.

Eleven forts protected the city in a ring about ten miles (16 km) long from Beargrass Creek to Paddy's Run. The first work built was Fort McPherson, which commanded the approaches to the city via the Shepherdsville Pike, Third Street Road, and the L&N Railroad. The fort was to serve as a citadel if an attack came before the other forts were completed. The fort could house one thousand men. General Hugh Ewing, Union commander in Louisville, directing that municipal authorities furnish laborers for fortifications, ordered the arrest of all "loafers found about gambling and other disreputable establishments" in the city for construction work, and assigned military convicts as laborers. It was typical of military commanders to press citizens into service.

Each fort was a basic earth-and-timber structure surrounded by a ditch with a movable drawbridge at the entrance to the fort. Each was furnished with an underground magazine to house two hundred rounds of artillery shells. The eleven forts occupied the most commanding positions to provide interlocking cross fire between them. A supply of entrenching tools was collected and stored for emergency construction of additional batteries and infantry entrenchments between the fortifications. As it happened, the guns in the Louisville forts were never fired except for salutes.

With orders No. 59 and No. 240, Burbridge began a campaign to suppress guerrilla activity in Kentucky and Louisville. On August 11, Burbridge commanded Captain Hackett of the 26th Kentucky to select four men to be taken from prison in Louisville to Eminence, Henry County, Kentucky, to be shot for unidentified outrages. On August 20, suspected Confederate guerrillas J. H. Cave and W. B. McClasshan were taken from Louisville to Franklin, Simpson County, to be shot for an unidentified reason. The commanding officer General Ewing declared that Cave was innocent and sought a pardon from Burbridge, but he refused. Both men were shot.[15]

On October 25, Burbridge ordered four men, Wilson Lilly, Sherwood Hartley, Captain Lindsey Dale Buckner and M. Bincoe, to be shot by Captain Rowland Hackett of Company B, 26th Kentucky for the alleged killing of a postal carrier near Brunerstown (present day Jeffersontown). This was in retaliation for the killing by guerrillas allegedly led by Captain Marcellus Jerome Clarke, sometimes called "Sue Mundy". On November 6, two men named Cheney and Morris were taken from the prison in Louisville and transported to Munfordville and shot in retaliation for the killing of Madison Morris, of Company A, 13th Kentucky Infantry. James Hopkins, John Simple and Samuel Stingle were taken from Louisville to Bloomfield, Nelson County, and shot in retaliation for the alleged guerrilla shooting of two black men. On November 15, two Confederate soldiers were taken from prison in Louisville to Lexington and hung at the Fair Grounds in retaliation. On November 19, eight men were taken from Louisville to Munfordville to be shot for retaliation for the killing of two Union men.[16]

By the end of 1864, Burbridge ordered the arrest of twenty-one prominent Louisville citizens, plus the chief justice of the State Court of Appeals, on treason charges. He had captured guerrillas brought to Louisville and hanged on Broadway at 15th or 18th Streets. General Ewing was effectively out of the loop and often bedridden from attacks of rheumatism. As he was ordered to rejoin his brother-in-law General Sherman, Ewing has escaped the condemnation of Burbridge's actions in Louisville.

By the November elections of 1864, Burbridge tried to interfere with the election for president. Despite military interference, Kentucky citizens voted overwhelmingly for Union General George B. McClellan over Lincoln. Twelve counties were not allowed to post their returns.[17] In December 1864, President Lincoln appointed James Speed as the U.S. Attorney General.[18]

War comes to a close (1865–66)

[edit]

Although the Confederacy began to fall apart in January 1865, Burbridge continued executing guerrillas. On January 20, 1865, Nathaniel Marks, formerly of Company A, 4th Kentucky, C.S. was condemned as a guerrilla. He claimed his innocence, but was shot by a firing squad in Louisville. On February 10, Burbridge's term as military governor came to an end. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton replaced Burbridge with Major General John Palmer.

On March 12, Union forces captured 20-year-old Captain M. Jerome Clarke, the alleged "Sue Mundy", along with Henry Medkiff and Henry C. Magruder, ten miles (16 km) south of Brandenburg near Breckinridge County. The Union Army hanged Clarke three days later just west of the corner of 18th and Broadway in Louisville, after a military trial in which he was charged as a guerrilla. During the secret three-hour trial, Clarke was not allowed counsel or witnesses for his defense, although he asked to be treated as a prisoner of war. Magruder was allowed to recover from war injuries before being executed by hanging on October 29.[19]

On April 9, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses Grant, and on April 14, Confederate General Joseph Johnston surrendered to Union General William T. Sherman, ending the Civil War.

On May 15, Louisville became a mustering-out center for troops from midwestern and western states. On June 4, 1865, military authorities established the headquarters of the Union Armies of the West in Louisville. During June 1865, 96,796 troops and 8,896 animals left Washington, D.C., for the Ohio Valley. There 70,000 men took steamboats to Louisville and the remainder embarked for St. Louis and Cincinnati. The troops boarded ninety-two steamboats at Parkersburg and descended the river in convoys of eight boats, to the sounds of cheering crowds and booming cannon salutes at every port city. For several weeks, Union soldiers crowded Louisville. On July 4, 1865, Union General William T. Sherman visited Louisville to conduct a final inspection of the Armies of the West. By mid-July the Armies of the West disbanded and the soldiers headed home.

Due to the Emancipation Proclamation, the severity of martial law under Burbridge and the enlistment of Kentucky slaves into Union regiments (Kentucky had the 2nd largest African American Union enlistment only behind Louisiana), Union support among native Kentuckians greatly diminished by war's end. This is documented in Louisville by prominent Washington, D.C. journalist Whitelaw Reid, who accompanied Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase for a tour of the south from May 1, 1865, to May 1, 1866. Reid observed in 1865 "At Louisville a pleasant dinner party enabled us to meet the last collection of men from the midst of a Rebel community. At that time there was more loyalty in Nashville than in Louisville, and about as much in Charleston as in either. For the first and only time on the trip, save while we were under the Spanish flag, slaves waited on us at dinner. They were the last any of us were ever to see on American soil." This sentiment is also evident in the daily violence between Louisville citizens and the Union soldiers mustering out of the city to their home states during this period in what was known as the "war after the war" throughout the state.[20][21]

On December 18, the Kentucky legislature repealed the Expatriation Act of 1861, allowing all who served in the Confederacy to have their full Kentucky citizenship restored without fear of retribution. The legislature also repealed the law that defined any person who was a member of the Confederacy as guilty of treason. The Kentucky legislature allowed former Confederates to run for office. On February 28, 1866, Kentucky officially declared the war over.[22]

Post-war

[edit]

After the war, Louisville returned to growth, with an increase in manufacturing, establishment of new factories, and transporting goods by train. The new industrial jobs attracted both black rural workers, including freedmen from the South, and foreign immigrants. It was a city of opportunity for them. Ex-Confederate officers entered law, insurance, real estate and political offices, largely taking control of the city. This led to the jibe that Louisville joined the Confederacy after the war was over.

Women sympathizing with the Confederacy organized many groups, including in Kentucky. During the postwar years, Confederate women ensured the burial of the dead, including sometimes allocating certain cemeteries or sections to Confederate veterans, and raised money to build memorials to the war and their losses. By the 1890s, the memorial movement came under the control of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and United Confederate Veterans (UCV), who promoted the "Lost Cause". Making meaning after the war was another way of writing its history.[23] In 1895, the women's group supported the erection of a Confederate monument near the University of Louisville campus.

"The Lost Cause" movement in Louisville primarily occurred between 1865 and 1935. This is due to most native Kentuckians coming to regret their decision to support the Union due to the war's upending of the antebellum racial and social hierarchy in Kentucky. One of the most notable personalities of Louisville during this time was that of Henry Watterson, a Confederate veteran and editor in chief of the newly formed Courier-Journal (1868). He was a major proponent of the New South Creed which emphasized a vision of a prosperous and independent South within an expanding American empire. He is the person who coined Louisville as being "The Gateway to the South". Watterson was one of the most important and widely read newspaper editors in American history. In the late 19th century the Courier-Journal had the largest circulation of any paper outside of New York and was the paper of record for Kentucky and that of the entire south. The Courier-Journal had four times the circulation of fellow New South advocate Henry W. Grady's Atlanta Constitution.[24][25]

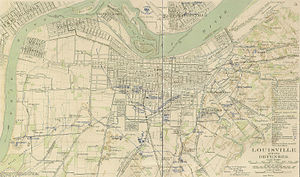

Civil War defenses of Louisville (1864–65)

[edit]Around 1864–65, city defenses, including eleven forts ordered by Union General Stephen G. Burbridge, formed a ring about ten miles (16 km) long from Beargrass Creek to Paddy's Run. Nothing remains of these constructions.[26] They included, from east to west:

- Fort Elstner between Frankfort Ave. and Brownsboro Road, near Bellaire, Vernon and Emerald Aves.

- Fort Engle at Spring Street and Arlington Ave.

- Fort Saunders at Cave Hill Cemetery.

- Battery Camp Fort Hill (2) (1865) between Goddard Ave., Barrett and Baxter Streets, and St. Louis Cemetery.

- Fort Horton at Shelby and Merriweather Streets (now site of city incinerator plant).

- Fort McPherson on Preston Street, bounded by Barbee, Brandeis, Hahn and Fort Streets.

- Fort Philpot at Seventh Street and Algonquin Parkway.

- Fort St. Clair Morton at 16th and Hill Streets.

- Fort Karnasch on Wilson Ave. between 26th and 28th Streets.

- Fort Clark (1865) at 36th and Magnolia Streets.

- Battery Gallup (1865) at Gibson Lane and 43rd Street.

- Fort Southworth on Paddy's Run at the Ohio River (now site of city sewage treatment plant). Marker at 4522 Algonquin Parkway.

Also in the area were Camp Gilbert (1862) and Camp C. F. Smith (1862), both at undetermined locations.

See also

[edit]- Louisville Mayors during the Civil War

- John M. Delph (1861–1863)

- William Kaye (1863–1865)

- Philip Tomppert (1865)

- Louisville-area Civil War monuments

- 32nd Indiana Monument within Cave Hill Cemetery

- Confederate Martyrs Monument in Jeffersontown

- Confederate Monument of Bardstown

- Confederate Soldiers Martyrs Monument in Eminence

- Confederate Monument in Louisville

- Louisville-area museums with Civil War artifacts

- Other Kentucky cities in the Civil War

Notes

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2009) |

- ^ Yater, p. 61.

- ^ Beach, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Beach, p. 18.

- ^ Beach, p. 20.

- ^ White, p. 11.

- ^ White, pp. 20, 36.

- ^ The Murder of General Nelson, Harper's Weekly, October 18, 1862.

- ^ Head, pp. 155–158.

- ^ a b James, Thomas. Life of Rev. Thomas James, by Himself Archived March 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Rochester, N.Y.: Post Express Printing Company, 1886, at Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, accessed June 3, 2010.

- ^ Pildes, Richard H., "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon" Archived November 21, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, pp. 12–13, accessed March 10, 2008.

- ^ Bullard, Gabe (March 16, 2014). "No, Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman Didn't Plan the March to the Sea in Louisville". Louisville, Kentucky: WFPL. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ McDowell, Robert E. (1962). City of Conflict: Louisville in the Civil War 1861–1865. Louisville Civil War Roundtable Publishers. p. 159.

- ^ Beach, pp. 154–156.

- ^ Beach, p. 177.

- ^ Beach, p. 184.

- ^ Beach, pp. 198, 201, 202.

- ^ Beach, p. 202.

- ^ Holmberg, James J. (2001). "Speed, James". In Kleber, John E. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Louisville. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 842. ISBN 0-8131-2100-0. OCLC 247857447.

- ^ Vest, Stephen M., "Was She or Wasn't He?," Kentucky Living, November 1995, pp. 25–26, 42.

- ^ Reid, Whitelaw (1866). After the War: A Southern Tour, May 1, 1865 to May 1, 1866. S. Low, Son, & Marston.

- ^ Courier Journal "Thanksgiving 1866: Ky's wounds of war unhealed" November 21, 2016

- ^ Beach, p. 228.

- ^ Blight, David, Race and Reunion: Civil War in American Memory, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001, pp. 258–260.

- ^ Marshall, Anne Elizabeth (2010). Creating a Confederate Kentucky: The Lost Cause and Civil War Memory in a Border State. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ Margolies, Daniel S. (November 24, 2006). Henry Watterson and the New South: The Politics of Empire, Free Trade, and Globalization. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky.

- ^ Johnson, Leland R. (1984). The Falls City Engineers a History of the Louisville District Corps of Engineers United States Army 1870–1983. United States Army Engineer District.

References

[edit]- Beach, Damian (1995). Civil War Battles, Skirmishes, and Events in Kentucky. Louisville, Kentucky: Different Drummer Books.

- Bush, Bryan S. (1998). The Civil War Battles of the Western Theatre (2000 ed.). Paducah, Kentucky: Turner Publishing, Inc. pp. 22–23, 36–41. ISBN 1-56311-434-8.

- Head, James (2001). The Atonement of John Brooks: The Story of the True Johnny "Reb" Who Did Not Come Marching Home. Florida: Heritage Press. ISBN 1-889332-42-9.

- Johnson, Leland R. A History of the Louisville District Corps of Engineers United States Army. pp. 103–120.

- McDowell, Robert E. (1962). City of Conflict: Louisville in the Civil War, 1861–1865. Louisville, Kentucky: Louisville Civil War Roundtable.

- Nevin, David (1983). The Road to Shiloh: Early Battles in the West. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books, Inc. pp. 11–12, 42–103. ISBN 0-8094-4712-6.

- Street, James (1985). The Struggle for Tennessee: Tupelo to Stones River. Richmond, Virginia: Time-Life Books, Inc. pp. 8–67. ISBN 0-8094-4760-6.

- Thomas, Samuel, ed. (1992) [1971]. Views of Louisville Since 1766. Louisville, Kentucky: Merrick Printing Company.

- White, J. Andrew (1993). Louisville on the Fingertips of an Invasion.

- Yater, George H. (1979). Two Hundred Years at the Falls of the Ohio: A History of Louisville and Jefferson County. Louisville, Kentucky: The Heritage Corporation. pp. 82–96. ISBN 0-9603278-0-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Bush, Bryan S. (2008). Lincoln and the Speeds: The Untold Story of a Devoted and Enduring Friendship. Morley, Missouri: Acclaim Press. ISBN 978-0-9798802-6-1.

- Bush, Bryan S. (2008). Louisville and the Civil War: A History & Guide. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-554-4.

- Cotterill, R. S. "The Louisville and Nashville Railroad 1861–1865," American Historical Review (1924) 29#4 pp. 700–715 in JSTOR

- Coulter, E. Merton (1926). The Civil War and Readjustment in Kentucky. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press.

- Reinhart, Joseph R. (2000). A History of the 6th Kentucky Volunteer Infantry, U.S.: The Boys Who Feared No Noise. Louisville, Kentucky: Beargrass Press.

External links

[edit]- "Joshua and James Speed" – Article by Civil War historian/author Bryan S. Bush (archived)

- Brief History of the 5th Kentucky Infantry from The Union Regiments of Kentucky