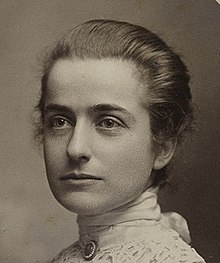

Lydia Weld

Lydia Weld | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1878 Boston |

| Died | January 5, 1962 (aged 83–84) Carmel, California |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

Lydia "Rose" Gould Weld (1878 – January 5, 1962) was one of the first women to graduate with an engineering degree from any college in the United States and the first in Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[1]

Biography

[edit]Lydia Weld was born as one of a pair of identical twins in 1878 in Boston. Her sister Julia always identified with a purple ribbon on her wrist and was known as Violet. Lydia wore pink and was called Rose. The Weld's traveled south for the winters; spent summers in Cape Cod and spending time in Virginia on the James River by houseboat. Weld played tennis, baseball and collected stamps.[2][3][4][5]

Weld was educated by governesses before going to finishing school. Weld was accepted at Bryn Mawr College but she needed to complete a class in English before attending. Instead she applied to MIT against her mother’s wishes. A professor suggested that she would quit after discovering the level of manual labour involved. She began at MIT in 1898 where she learned blacksmithing and locomotive design while completing a degree in Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering.

Upon graduating in 1903, Weld got a job as a draughtsman in the engineering division of Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company. Weld's role was to produce all the plans for machinery to be installed on naval ships. She became a member of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, one of the first two women allowed to join alongside Kate Gleason.[6] She was an associate member until 1935 when women were permitted to join as full members. Weld worked from 1903 to 1917 at the shipyard, in charge of the tracing department. She was forced to resign due to a chronic bronchial condition.[2][3][4][7][8][9][10][11][5][12][13][14][15]

Weld moved to live with her brother in California in 1918 where she managed 320 acres of his ranch until 1933. As usual, she took a course in the University of California Davis before taking on the role. Until 1917 Weld taught Sunday school for St. Paul’s Episcopal in Newport News, and in California she got involved in the League of Women Voters. She also assisted with the Right to Work Campaign. Weld was always involved in her MIT alumni activities.[2][3][4][8][5]

After hearing of the attack on Pearl Harbor Weld volunteered and became a ground observer on a 40-foot tower at Cypress Point in California. She was on duty from 4:00 to 8:00 a.m. She also took a course airplane design in University of California at Berkeley. She became the only engineer working as the senior draughtsman for Moore’s Dry Dock Company in Oakland, California.[16] She retired again in 1945. Weld lived in San Francisco and died on January 5, 1962. She is buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery near Boston.[2][3][4][17][5]

References and sources

[edit]- ^ "woman graduate naval architect". Daily Press. 2 September 1962. p. 39.

- ^ a b c d "The Mariners' Museum" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d "Women engineers. | MIT ArchivesSpace". archivesspace.mit.edu.

- ^ a b c d "TECHNOLOGY REVIEW 1959" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d "Miss Lydia "Rose" Gould Weld". Answering America's Call.

- ^ "The Woman Engineer Vol 1". www2.theiet.org. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- ^ Bix, Amy Sue (31 January 2014). Girls Coming to Tech!: A History of American Engineering Education for Women. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262320276.

- ^ a b Gurba, Norma (2013). Legendary Locals of the Antelope Valley. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-0087-8.

- ^ Alexander, Philip N. (2011). A Widening Sphere: Evolving Cultures at MIT. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-29438-6.

- ^ Tietjen, Jill S. (2016). Engineering Women: Re-visioning Women's Scientific Achievements and Impacts. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-40800-2.

- ^ "The Timeline of Events in the History of Women Engineering | Kibin". www.kibin.com.

- ^ "OTHER WOMEN AND THE WATER" (PDF).

- ^ "ASME" (PDF).

- ^ "MIT Technology Review 1955-11". November 1955.

- ^ "Gals & Guns: Women in American Engineering Pre-World War II". Subway Reads.

- ^ "Collection: Lydia G. Weld papers | MIT ArchivesSpace". archivesspace.mit.edu. Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ Hatch, Sybil E. (2006). Changing Our World: True Stories of Women Engineers. ASCE Publications. ISBN 978-0-7844-0835-3.