Cromford and High Peak Railway

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

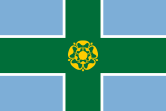

| Locale | Derbyshire, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dates of operation | 1831–1967 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | High Peak Trail cycleway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Cromford and High Peak Railway (C&HPR) was a standard-gauge line between the Cromford Canal wharf at High Peak Junction and the Peak Forest Canal at Whaley Bridge. The railway, which was completed in 1831, was built to carry minerals and goods through the hilly rural terrain of the Peak District within Derbyshire, England. The route was marked by a number of roped worked inclines. Due to falling traffic, the entire railway was closed by 1967.

The remains of the line, between Dowlow and Cromford, has now become the High Peak Trail, a route on the National Cycle Network.

Background

[edit]

The Peak District of Derbyshire has always posed problems for travel, but from 1800 when the Peak Forest Canal was built, an alternative to the long route through the Trent and Mersey Canal was sought, not only for minerals and finished goods to Manchester, but raw cotton for the East Midlands textile industry.

One scheme that had been suggested would pass via Tansley, Matlock and Bakewell. In 1810, a prospectus was published for another route via Grindleford, Hope and Edale, but since it could only promise £6,000 a year, in return for an outlay of £500,000, it was received with little enthusiasm. The problem was not only carrying a canal over a height of around a thousand feet, but supplying it with water on the dry limestone uplands.

Finally Josias Jessop, the son of William Jessop, was asked to survey the route. He, his father and their former partner Benjamin Outram had gained wide experience in building tramways where conditions were unsuitable for canals, and that is what he suggested. Even so, as almost the first long-distance line at 33 miles (53 km), it was a bold venture. Moreover, to its summit at Ladmanlow, it would climb a thousand feet from Cromford, making it one of the highest lines ever built in Britain.

| Cromford and High Peak Railway Act 1825 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for making and maintaining a Railway or Tram Road from Cromford Canal, at or near to Cromford, in the Parish of Wirksworth, in the County of Derby, to the Peak Forest Canal, at or near to Whaley (otherwise Yardsley-cum-Whaley), in the County Palatine of Chester. |

| Citation | 6 Geo. 4. c. xxx |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 2 May 1825 |

The Cromford and High Peak Railway Act 1825 (6 Geo. 4. c. xxx) was obtained for a "railway or tramroad" to be propelled by "stationary or locomotive steam engines," which was remarkably prescient, considering few people considered steam locomotives to be feasible, and George Stephenson's Stockton and Darlington Railway was barely open in far-away County Durham.

Construction

[edit]

The first part of the line from the wharf at High Peak Junction, on the Cromford Canal, to Hurdlow opened in 1830. From the canal it climbed over one thousand feet (305 m) in five miles (8 km), through three inclines ranging from 1 in 14 (7.1%) to 1 in 8 (12.5%): Sheep Pasture incline near Cromford and Middleton and Hopton inclines above Wirksworth. The line then proceeded up the relatively gentle Hurdlow incline at 1 in 16 (6.25%). The second half from Hurdlow to Whaley Bridge opened in 1832 descending through four more inclines, the steepest being 1 in 7 (14.3%). The highest part of the line was at Ladmanlow, a height of 1,266 feet (386 m). For comparison, the present-day highest summit in England is Ais Gill at 1,169 feet (356 m) on the Settle–Carlisle line, although the remaining, freight-only, stub of the CHPR at Dowlow Lime Works reaches a height of 1,250 feet (381 m).

The railway was laid using so-called "fishbelly" rails supported on stone blocks, as was common in those days, rather than timber sleepers, since it would be powered by horses on the flat sections. On the nine inclined planes, stationary steam engines would be used, apart from the last incline into Whaley Bridge, which was counterbalanced and worked by a horse-gin. The engines, rails and other ironwork were provided by the Butterley Company. It would take around two days to complete the journey. It was laid to the Stephenson gauge of 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm), rather than Outram's usual 4 ft 2 in (1,270 mm).

While its function was to provide a shorter route for Derbyshire coal than the Trent and Mersey Canal, it figured largely in early East Midlands railway schemes because it was seen as offering a path into Manchester for proposed lines from London. However, the unsuitability of cable railways for passengers became clear within a few years.

Part of the route included the Hopton Incline. This was a very steep section of the railway about a mile north of the small village of Hopton. It was originally worked by a stationary steam engine but was modified later to be adhesion worked by locomotives. At 1 in 14 (7%), it was the steepest in Britain and trains frequently had to be split and pulled up a few wagons at a time. The route also required the construction of a number of tunnels, including those at Hopton and at Newhaven.[1][2]

Dozens of small sidings were added along the length of the railway to accommodate the wagons that worked the line. Towards the Cromford end, between Sheep Pasture Top and Friden there were over 15 sidings, mostly grouped between Sheep Pasture and Longcliffe, primarily serving quarries. One was built in 1883 from Steeplehouse to serve the Middleton Quarry north of Wirksworth. The branch closed in 1967 but the trackbed was later used for the 18 in (457 mm) Steeple Grange Light Railway in 1985.

Towards the Whaley Bridge end of the line, another profusion of sidings lay between Dowlow Halt and Ladmanlow, mostly serving quarries and limeworks. This included some dozen sidings in the short section between Harpur Hill and Old Harpur.

The following table lists the inclines as originally built:[3]

| Incline | Length | Gradient | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cromford | 580 yards (530 m) | 1 in 9 (11.1%) | Combined with Sheep Pasture in 1857,[4] combined name "Sheep Pasture Incline" |

| Sheep Pasture | 711 yards (650 m) | 1 in 8 (12.5%) | Combined with Cromford in 1857,[4] combined name "Sheep Pasture Incline" |

| Middleton | 708 yards (647 m) | 1 in 8+1⁄2 (11.8%) | |

| Hopton | 457 yards (418 m) | 1 in 14 (7.1%) | Chain-hauled until 1877, adhesion thereafter[5][6] |

| Hurdlow | 850 yards (777 m) | 1 in 16 (6.3%) | Bypassed and abandoned 1869[7] |

| Bunsall Upper | 660 yards (604 m) | 1 in 17+1⁄2 (5.7%) | Combined with Bunsall Lower in 1857,[4] combined name "Bunsall Incline", abandoned 1892 |

| Bunsall Lower | 455 yards (416 m) | 1 in 7 (14.2%) | Combined with Bunsall Upper in 1857,[4] combined name "Bunsall Incline", abandoned 1892 |

| Shallcross | 817 yards (747 m) | 1 in 10+1⁄4 (9.8%) | Abandoned 1892 |

| Whaley Bridge | 180 yards (165 m) | 1 in 13+1⁄2 (7.4%) | Abandoned 1952 |

Expansion

[edit]

The line had been built on the canal principle of following contours across the plateau and the many tight curves hampered operations in later years. Not only did the C&HPR have the steepest adhesion worked incline of any line in the country, the 1 in 14 of Hopton, it also had the sharpest curve, 55 yards (50 m) radius through eighty degrees at Gotham.[8]

The line was isolated until 1853 when, in an effort to improve traffic, a connection was made with the Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midland Junction Railway at High Peak Junction a short way south of the terminus at Cromford. In 1857 the northern end was connected to the Stockport, Disley and Whaley Bridge Railway. Around this time, the people of Wirksworth were agitating for a line and an incline was built between the two. However, the Midland Railway began surveying a line from Duffield[9] in 1862 but it was never used.[10]

The C&HPR was leased by the London and North Western Railway in 1862, being taken over fully in 1887. By 1890 permission had been obtained to connect the line directly to Buxton by building a new line from Harpur Hill the two or three miles into the town centre, thus frustrating the Midland Railway's original plans for a route to Manchester.

The old north end of the line from Ladmanlow (a short distance from Harpur Hill) to Whaley Bridge via the Goyt Valley was largely abandoned in 1892, though the track bed is still visible in many places and one incline forms part of a public road.

Then, built by the LNWR, the branch line to Ashbourne was opened in 1899. This used the section of the C&HP line from Buxton as far as Parsley Hay, from where a single line ran south to Ashbourne, where it connected with the North Staffordshire Railway. The formation was constructed to allow for double tracking if necessary, but this never happened.

Operation

[edit]

The line was worked by independent contractors until long after other lines, which had taken operations in house upon the introduction of locomotives. The line was initially under-capitalised because many of the subscribers did not meet their dues, and it was mainly funded by the Butterley Company, a major supplier and its main creditor. The final cost was £180,000, more than Jessop's estimate of £155,000, but still much cheaper than a canal. Nevertheless, the line never achieved a profit. Francis Wright, the Chairman, was later to say, in 1862 "We found ourselves getting into difficulties from the third year of our existence," and added it was clear in retrospect that the line "never had a remote chance of paying a dividend on the original shares."[11]

The railway's first steam locomotive arrived in 1841 with Peak, built by Robert Stephenson and Company. By 1860 the line had six more locomotives gradually displacing the horses. Because the inclines were too steep for adhesion traction by these early locomotives they were hauled up and down the inclines, along with their trains, by static steam engines. The hemp rope or chains initially used for hauling trains were later replaced by steel cables.

| Cromford and High Peak Railway Act 1855 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to alter and extend the Line of the Cromford and High Peak Railway, and to amend and consolidate the Provisions of the Acts relating thereto. |

| Citation | 18 & 19 Vict. c. lxxv |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 26 June 1855 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

The Cromford and High Peak Railway Act 1855 (18 & 19 Vict. c. lxxv) authorised the carriage of passengers. However the one train per day each way did little to produce extra revenue and, when a passenger was killed in 1877, the service was discontinued. The line's prosperity depended on that of the canals it connected but, by the 1830s, they were in decline. This was, to a degree, offset by the increase in the trade for limestone from the quarries.

There were, in fact, very few accidents. In 1857, the Cromford and Sheep Pasture inclines had been merged into one, and in 1888, a brake van broke away from a train near the summit. Gathering speed, it was unable to round the curve into Cromford Wharf. It passed over both the canal and the double track railway line, and landed in a field. A catch pit was therefore installed near the bottom. This can still be seen from the A6[12] with a (more recent) wrecked wagon still in it.

The most serious accident occurred in 1937. The line was fairly level on the approach to the Hopton Incline and it was custom to gain speed for the uphill gradient. There was a shallow curve immediately before and on this occasion the locomotive spread the track, rolled over and down the embankment with four wagons. The driver was killed and thereafter a speed limit of 40 mph (64 km/h) was strictly enforced.

During World War II, the line was used to transport bombs to the large underground munitions store at RAF Harpur Hill. The railway line ran directly through the site.[13]

Demise

[edit]Traffic – by now almost exclusively from local quarries – was slowly decreasing during the Beeching era, the first section of the line being closed in 1963. This was the rope-worked 1 in 8 Middleton Incline. The Middleton Top-Friden section, including the 1 in 8 Sheep Pasture Incline and the Hopton Incline, closed on 21 April 1967[14] and Friden to Hindlow closed on 2 October 1967.[15]

Preservation

[edit]The High Peak Trail

[edit]

In 1971 the Peak Park Planning Board and Derbyshire County Council bought part of the track bed (from Dowlow, near Buxton, to High Peak Junction, Cromford) and turned it into the High Peak Trail, now a national route of the National Cycle Network and popular with walkers, cyclists and horse riders.

The High Peak Trail and part of the Tissington Trail (see below) are now also designated as part of the Pennine Bridleway, a leisure route that starts at Middleton Top, near Cromford, and includes 73 miles (117 km) through Derbyshire to the South Pennines.

The Middleton Incline Engine House has also been preserved, and the ancient engine once used to haul loaded wagons up is often demonstrated.[16] Another attraction along the route is the Steeple Grange Light Railway, a narrow-gauge railway running along the trackbed of a branch line off the C&HPR.

Near Cromford at the top of the town of Wirksworth the railway passed under Black Rocks, a popular gritstone climbing ground, and gave the name to the 'railway slab', a short tricky 'boulder problem' by the railway track.

The Tissington Trail

[edit]At the hamlet of Parsley Hay, about 5 miles (8 km) SW of Bakewell, the C&HPR/High Peak Trail is joined by the Tissington Trail, another route of the National Cycle Network, and formerly the railway line from Buxton to Ashbourne. This 13-mile (21 km) recreational route runs from Parsley Hay to Ashbourne on a gently descending gradient.

Station locations

[edit]Cromford and High Peak Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Harpur Hill–Ladmanlow

straightening (1875) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Harpur Hill–Hindlow

realignment (1892) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hurdlow Incline

deviation (1869) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Passenger services were introduced in stages with there being only one service a day each way between Cromford and Landmanlow in 1856. Stations were included at:

- Whatstandwell

- Cromford

- Steeple House

- Middleton

- Hopton Top Wharf

- Longcliffe

- Friden

- Hurdlow

- Hindlow

- Ladmanlow

The following additional stations were added in 1874. However, this was short-lived and the line was closed to passengers along with the outlying halts and minor stations in 1876.

- Whatstandwell

- Cromford

- Sheep Pasture

- Steeple House

- Middleton

- Hopton Top Wharf

- Longcliffe

- Friden

- Hurdlow

- Parsley Hay

- Hindlow

- Harpur Hill

- Ladmanlow

- Bunsail

- Shallcross

- Whaley Bridge

When in operation the services offered interchanges with the Derwent Valley Line, Ashbourne Line and Manchester, High Peak and Derbyshire Railway. [17]

References

[edit]- ^ "Hopton Tunnel: Derbyshire Historic Environment Record MDR9474". Derbyshire County Council. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ "Newhaven Tunnel: Derbyshire Historic Environment Record MDR1592". Derbyshire County Council. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ Marshall 2011, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Marshall 2011, p. 28.

- ^ Jones & Bentley 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Rimmer 1956, p. 17.

- ^ Marshall 2011, p. 57.

- ^ Kingscott 2007, p. 32.

- ^ see Ecclesbourne Valley Railway

- ^ Kingscott 2007, p. 27.

- ^ Moorsom and the Attempt to Revive the Cromford And High Peak Railway Derbyshire Archaeological Journal 1983 doi:10.5284/1066470

- ^ "Geograph:: Runaway crash tunnel on the High Peak... © Andrew Abbott". www.geograph.org.uk. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ Neville, Lea (2002). Return To Buxton - 28 MU RAF Harpur Hill. Woodcote Press. pp. 57, 70.

- ^ Modern Railways. July 1967. p. 398.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Parsley Hay Station". disused-stations.org.uk. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ "Middleton Top Engine". Archived from the original on 21 October 2005. Retrieved 7 October 2005.

- ^ "Disused Stations: Parsley Hay Station".

Sources

[edit]- Jones, Norman; Bentley, J. M. (2001). Railways of the High Peak: Onwards to Cromford and High Peak Junction. Scenes from the Past. Stockport: Foxline. ISBN 978-1-870119-67-2. No. 37 (Part 2).

- Kingscott, Geoffrey (2007). Lost Railways of Derbyshire. Newbury, Berkshire: Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-84674-042-8.

- Marshall, John (2011). The Cromford & High Peak Railway. Leeds: Martin Bairstow. ISBN 978-1-871944-39-6.

- "The High Peak Railway in Wartime". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 90, no. 551. London: Tothill Press Limited. May 1944. pp. 152, 164–165. ISSN 0033-8923.

- Rimmer, A. (1956). The Cromford & High Peak Railway. Lingfield, Surrey: Oakwood Press. OCLC 6091497. Locomotion Papers 10.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cromford and High Peak Railway at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cromford and High Peak Railway at Wikimedia Commons

- Railway companies established in 1825

- Railway companies disestablished in 1887

- Railway lines opened in 1831

- British companies established in 1825

- Early British railway companies

- London and North Western Railway

- Railway inclines in the United Kingdom

- Rail transport in Derbyshire

- Closed railway lines in the East Midlands

- Horse-drawn railways

- Portage railways

- Peak District