Greenville, Jersey City

Greenville, Jersey City | |

|---|---|

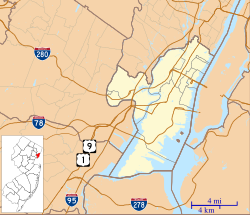

Greenville is located between the Newark Bay and Upper New York Bay | |

| Coordinates: 40°42′01″N 74°05′40″W / 40.70028°N 74.09444°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Hudson |

| City | Jersey City |

| Elevation | 62 ft (19 m) |

| Area code | 201 |

| GNIS feature ID | 876803[1] |

Greenville is the southernmost section of Jersey City in Hudson County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.[2][3][4][5]

Geography

[edit]

In its broadest definition, Greenville encompasses the area south of the West Side Branch of Hudson-Bergen Light Rail and north of the city line with Bayonne, between the Upper New York Bay and the Newark Bay, and corresponds to the postal area ZIP Code 07305.

The central core of Greenville (between Garfield Avenue and West Side Avenue) is primarily residential, consisting mostly of one- and two-family homes and lowrise apartment buildings. Principal thoroughfares include MLK Drive, Old Bergen Road and Danforth Avenue.

East of New Jersey Turnpike Newark Bay Extension (Interstate 78) lie the Greenville Yard, an intermodal facility,[6] Port Jersey, Port Liberté, (a gated residential community), and the Caven Point Section of Liberty State Park. Slightly further inland and parallel to the route of the Turnpike was the route of the Morris Canal until it was abandoned in the 1920s. A small (filled-in) portion of the canal still exists in Country Village,[7] a neighborhood near Droyer's Point and the West Side. The Claremont Section straddles Greenville and Bergen-Lafayette.[citation needed]

Greenville parks include Bayside Park, off Garfield Avenue, Audubon Park, a city square along John F. Kennedy Avenue, Fulton Avenue Park along Martin Luther King Drive, McGovern Park, Columbia Park, and Mercer Park, just north of Interstate 78. Cochrane Athletic Field is located near the Hudson Waterfront.[8] In May 2020, construction started on Mary McLeod Bethune Park.[9]

The Afro-American Historical and Cultural Society Museum is located at the Greenville Branch of the Jersey City Free Public Library,[10] Greenville Hospital, Henry Snyder High School, and New Jersey City University all located on the district's main thoroughfare, Kennedy Boulevard. Greenville Hospital closed in 2008,[11] was renovated, and is now part of Barnabas Health which operates Jersey City Medical Center.[12] Greenville is also home to historic Bayview – New York Bay Cemetery, which includes a Commonwealth war grave, of a World War I seaman and 1800s opera singer, Lillian Nordica.

History

[edit]Minkakwa, Kewan, and Pamrapo

[edit]What became Greenville was the territory of the Hackensack and Raritan Indians at the time of European contact in the 17th century. They called the area on Bergen Neck Minkakwa (alternatively spelled Minelque and Minackqua) meaning "a place of good crossing". This is likely so because it was the most convenient pass between the two bays on either side of the neck. Interpreted as "place where the coves meet", in this case where they are closest to each, it describes a spot advantageous for portage.[13] The area was first settled by New Netherlanders in 1647.[14] The Caven Point settlement on the west shore of the Upper New York Bay between Pamrapo and Communipaw was part of Pavonia, which, upon receiving its municipal charter in 1661 was renamed Bergen. The name Caven is an anglicisation of the Dutch word Kewan,[15] which in turn was a "Batavianized"[16] derivative of an Algonquian word meaning "peninsula".[17]

Bergen, Greenville, Jersey

[edit]

During the British and early American colonial era the area was part of Bergen Township. The 19th century Jersey City and Bergen Point Plank Road (today's Garfield Avenue) ran through Greenville (from Paulus Hook to Bergen Point). Greenville became part of the newly formed Hudson County in 1840. The town grew as a fashionable suburb of New York City.[18] Greenville Township was incorporated as a township by an Act of the New Jersey Legislature on April 14, 1863, from portions of Bergen Town.[19] It was absorbed into Jersey City on February 4, 1873, ending its life as an independent municipality.[19][20] Armbruster's Greenville Schuetzen Park on Hudson Boulevard opened in the 1870s.[21]

20th century

[edit]Greenville was settled by many working-class Irish Catholic families, as well as other ethnic groups. The area's demographics changed dramatically starting in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, with the decline of factories and the collapse of the independent railroad lines. The neighborhood east of Kennedy Boulevard was later settled by African Americans, while that west of Kennedy Boulevard is more diverse with a sizable Filipino population. Greenville also has a sizable Hispanic and Egyptian population, and many of the older Irish residents still remain in the neighborhood.[citation needed]

21st century

[edit]

In 2005, Jersey City enacted a curfew for business owners on some of Greenville, including Martin Luther King Drive and Ocean Avenue.[22] On the West Side of Greenville, New Jersey City University unveiled plans for a $350 million expansion into the West Side neighborhood surrounding the university, including a performance art building with two theaters, retail stores, a restaurant, and student housing.[23]

During the 2010s Greenville underwent a revitalization, with the return of long-term residents and businesses.[24][25] The section around Jackson Hill has seen considerable local and federal infrastructure spending.

The area is considered, relative to Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens, to be an affordable part of the New York City region. A number of Ultra-Orthodox Jews and young Jewish and Hispanic families have purchased homes and built a growing community in Greenville.[26][27] Since the mid-2010s Jersey City has experienced a rise in Hasidic Orthodox Jews, who are moving to Greenville from Williamsburg, Brooklyn, attracted by the relatively low housing price. While the relationship between the local African American community and the Orthodox Jewish community is good, there have been complaints that Jewish buyers solicited them to sell their houses, prompting the city council to pass a no-knock ordinance that barred investors from going door-to-door.[26][28] A kosher market in the community was the site of a shootout in the 2019 Jersey City shooting.[29][30][31][32]

Increasing gentrification continues to make Greenville more multicultural.[33]

Public transportation

[edit]

The Richard Street and Danforth Avenue stations of the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail are located on the district's east side east of Garfield Avenue, while West Side Branch Hudson-Bergen Light Rail stations (including the MLK Station) are on its northern perimeter, which overlaps Bergen-Lafayette. Several New Jersey Transit bus routes serve this area. The Greenville Bus Garage on Old Bergen Road is one of the largest in Hudson, housing more than 120 buses for several New Jersey Transit Routes.

Notable residents

[edit]- George McAneny (1869–1953), Manhattan Borough President and New York City Comptroller

See also

[edit]- Bergen Neck

- Black Tom explosion

- Canal Crossing

- Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel

- Hackensack RiverWalk

- Hudson River Waterfront Walkway

- Greenville and Hudson Railway

- Liberty National Golf Club

- Liberty State Park

- List of neighborhoods in Jersey City, New Jersey

- New Jersey Route 185

- Red & Tan in Hudson County

- Roosevelt Stadium

- Route 440

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Greenville". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ Locality Search, State of New Jersey; accessed February 7, 2015.

- ^ "Jersey City's Districts". Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ "Greenville". Jersey City A to Z. New Jersey City University. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ Hudson County New Jersey Street Map. Hagstrom Map Company, Inc. 2008. ISBN 978-0-88097-763-0.

- ^ NY Harbor Intermodal Facilities Archived June 12, 2011, at archive.today, panynj.gov; accessed May 3, 2020.

- ^ Morris Canal Archived December 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, JerseyCityonline.com; accessed May 3, 2020.

- ^ "Parks".

- ^ "Construction Starts on Mary McLeod Bethune Park in Jersey City". Jersey Digs. May 19, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Afro-American Historical Society Museum, cityofjerseycity.org; accessed May 3, 2020.

- ^ Jersey City Medical Center, nj.com; accessed May 3, 2020.

- ^ "New Jersey Health System".

- ^ http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=moa&cc=moa&sid=95e3f6e828e116b80d4cccd93c806bc1&view=text&rgn=main&idno=AFJ8379.0001.001 page 50

- ^ Klett, Joseph. "An Account of East Jersey's Seven Settled Towns, circa 1684" (PDF). The Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey. 80 (September 2005): 106–114. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ Ferretti, Fred (June 10, 1979), "Jersey City Hopes to Save Caven Point", The New York Times

- ^ Shorto, Russell (2004). The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony that Shaped America. Random House. ISBN 1-4000-7867-9.

- ^ Winfield, Charles (1874). HISTORY OF THE COUNTY OF HUDSON, NEW JERSEY: From its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time. New York: Kennaud & Hay Stationery M'fg and Printing Company. p. 51.

- ^ "High Fares In Jersey.; Steps Taken By The Residents Of Greenville To Remedy Them" (PDF). The New York Times. May 13, 1881.

- ^ a b "The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968", John P. Snyder, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 146.

- ^ "Municipal Incorporations of the State of New Jersey (according to Counties)" prepared by the Division of Local Government, Department of the Treasury (New Jersey); December 1, 1958, p. 78 - Extinct List.

- ^ "Armbruster's Greenville Schuetzen Park - Jersey City Past and Present - Library Guides at New Jersey City University". njcu.libguides.com. Archived from the original on June 2, 2019.

- ^ Jersey City Curfew Tackles Crime, but May Hit Profits, Too, The New York Times, March 25, 2005

- ^ "Jersey City building boom coming to NJCU campus with $350M plan". NJ.com. September 3, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ "GSECDC's Home Ownership Initiative is Revitalizing Greenville One Home at a Time". July 5, 2017.

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b Berger, Joseph (August 2, 2017). "Uneasy Welcome as Ultra-Orthodox Jews Extend Beyond New York". The New York Times. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ "Orthodox Jews Arrive in Jersey City Neighborhood, Raising Hopes and Fears". m.youtube.com. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ "Orthodox Jews Arrive in Jersey City Neighborhood, Raising Hopes and Fears". NJTV. April 22, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ Knoll, Corina (December 15, 2019). "How 2 Drifters Brought Anti-Semitic Terror to Jersey City". The New York Times. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ De Avila, Joseph; Blint-Welsh, Tyler (December 11, 2019). "New Jersey Shooters Targeted Kosher Grocery Store, Jersey City Mayor Says". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ Helfand, Zach (December 11, 2019). "Untangling the Hate at the Heart of the Mass Shooting in Jersey City". The New Yorker. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ Sales, Ben; Adkins, Laura E. (December 11, 2019). "Orthodox Jews tried to build a home in Jersey City. Then a shooting terrorized their community". Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

- ^ "Gentrification In The Making For 40 Years In Jersey City & It Might Have Saved The City". Hudson County Chronicles. Retrieved April 2, 2021.