Mundigak

Mundigak منډیګک | |

|---|---|

Archeological site | |

| |

| Coordinates: 31°54′14″N 65°31′29″E / 31.9039°N 65.5246°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Kandahar |

Mundigak (Pashto: منډیګک) is an archaeological site in Kandahar province in Afghanistan. During the Bronze Age, it was a center of the Helmand culture. It is situated approximately 55 km (34 mi) northwest of Kandahar near Shāh Maqsūd, on the upper drainage of the Kushk-i Nakhud River.

History

[edit]

Mundigak was a large prehistoric town with an important cultural sequence from the 5th–2nd millennia BCE. It was excavated by the French scholar Jean Marie Casal in the 1950s.[1] The mound was nine meters tall at the time of excavation.[2]

Pottery and other artifacts form the later 3rd millennium BCE, when this site became a major urban center, indicate interaction with Turkmenistan, Baluchistan, and the Early Harappan Indus region.

Mundigak flourished during the culture of the Helmand Basin (Seistan), also known as the Helmand culture (Helmand Province).[3]

With an area of 21 hectares (52 acres), this was the second largest centre of the Helmand Culture, the first being Shahr-i-Sokhta which was as large as 150 acres (60 hectares), by 2400 BCE.[4]

Bampur in Iran is a closely related site.

Earlier, it was thought that around 2200 BCE, both Shahr-i-Sokhta and Mundigak started declining, with considerable shrinkage in area and with brief occupation at later dates.[5]

Excavations

[edit]During the French Archaeological Mission (MAI)[6] excavations from 1951 to 1958 in ten campaigns under the direction of Jean Marie Casal[7] with the support of the DAFA,[8] different levels of settlement could be distinguished. The excavations took place in eleven places in the excavation area. On Tépé (hill) A, the highest point in the city, remains of a palace were excavated in Period IV, level 1 and Period V. Urban areas from almost all periods of the place were found here. Area C is northwest of Area A. Only a small area has been excavated here, with the remains reaching back to Period III. In the other parts of the city, various, larger or smaller areas were exposed (areas B, D to I and P and R), whereby mainly remnants of Period IV came to light, which is therefore the best documented layer. In area P, remnants of Period V came to light, which is otherwise only documented in area A. The upper layers in particular had completely disappeared as a result of erosion. In area A, a large palace was uncovered in Period V on the remains of the older palace. Otherwise, however, Period V is not easy to cover in the city.[9] Most of the finds are now in the National Museum in Kabul and in the Museum Guimet in Paris. The excavator Jean Marie Casal had been employed in the latter museum since 1957.

New Research

[edit]The new research shows the site of Mundigak presents four periods of occupation from its early days till its urban development:[10]

| Period | Chronology | Phase |

|---|---|---|

| I | (~4000–3800 BCE) | Ph. 1-2 |

| I | (~3800–3400 BCE) | Ph. 3-4 |

| II | (~3400–3200 BCE) | |

| III | (~3200–2900 BCE) | |

| IV | (~2900–2400 BCE) |

On the other hand, archaeologists Jarrige, Didier, and Quivron considered that Periods III and IV in Mundigak have archaeological links with Periods I, II, and III in Shahr-i Sokhta.[11]

Period I to III

[edit]

The lowest layer of Period I in Mundigak was only excavated in the central mound (area A). It probably dates to the fifth millennium BC.[12] Period I was divided into five layers by the excavator (Period I, layers 1–5). The first evidence of permanent buildings comes from layer 3. House floor plans have only been preserved for layers 4 and 5. In these layers the buildings were rather simple. These are rectangular adobe residential buildings that consisted of one to three small rooms.[13] The ceramic from Period I is mainly made by open forms. In particular, shell fragments have been found. The ceramic is partly painted, with simple geometric patterns predominating. Painted animals are also very rare.[14] Period I.5 and the following Period II were separated by a thick layer of ash, which suggests that the place was uninhabited for a long time, at least in this area.[15]

Period II was divided into four layers by the excavator: II.1, II.2, II.3a and II.3b. The population density in area A increased. Various multi-room buildings could be excavated. There was a deep well in one courtyard. Compared to layer I, however, the quality of the ceramic decreases. There are a lot less painted types. Many pots are rather roughly worked.[16]

Period III is again mainly known from area A, where six layers were distinguished. From area C come the remains of a cemetery that was still occupied by Period IV. The dead lay here in a crouched position. There were hardly any additions. Only in one case were pearls used as a bracelet. The development in area A is now even more dense. They are mostly smaller houses with two or three rooms. Seals with geometric patterns also come from this layer.

Period IV

[edit]

In Period IV, Mundigak developed into a fully developed city with a palace and temple. It can be concluded that there is an advanced social structure. However, there is no evidence for the use of writing. The excavator distinguished three layers: IV.1, IV.2 and IV.3.

Palace

[edit]In the center of the city is hill A, on which extensive remains of a palace complex were found. It is uncertain whether it was really a palace as the excavator suspected, but the construction undoubtedly served a public function. The building was extensively surrounded by a wall. To create a platform for the construction, older houses standing on the hill were leveled. The north facade of the palace was decorated with a row of pilasters that were stuccoed and painted white. At the top, these pilasters were bordered by a decorated tile strip. Some of them were still two meters high when they were excavated. The actual palace consisted of various rooms and a courtyard. The east, south and west facades of the building were not preserved, but they may also have been decorated with pilasters. It was possible to distinguish between three renovation phases, all of which date to Period IV, layer 1. The later palace from Period IV, layer 2 and Period IV, layer 3 had completely fallen victim to the renovation work in Period V.

Temple

[edit]About 200 m east of the palace stood a monumental building that was probably a temple built on virgin soil. It stood on a flat, approximately 2.5 m high hill and had a monumental outer wall, which was decorated on the outside with mighty buttresses, triangular in plan. The foundations were made of stone. Inside the complex was a courtyard with the actual temple in the middle.[17]

About 350 m south of hill A, parts of another large adobe building were excavated (excavation area F), which certainly also had a public function. There was a courtyard with a large water basin and various rooms arranged around it.[18]

Wall and residential city

[edit]The residential quarters have only been partially excavated. To the west of the palace the remains of a wall could be traced in various places. It consisted of two outer walls. The interior was divided by partitions; this created a series of interior rooms that were accessible through doors on the inside of the wall. There were supporting pillars on the outer facade. A corner of the wall has been found. Here stood a tower with four interiors and once with perhaps four support pillars on each side. Only on the north side are all four preserved. Even in Period IV, layer 1, the area around the wall was densely built on both sides with simple houses, mostly consisting of a few rooms. The function of this wall is uncertain; it may have enclosed the palace extensively. About 90 m to the west (excavation area E) were again the remains of a second wall, which was constructed similarly and could be traced over a length of about 120 m. This was probably the actual city wall. Residential buildings were mostly found in excavation area D, where the city wall still stood in Period IV.1; on the other hand, the area in Period IV.2 was built on with simple residential buildings.

-

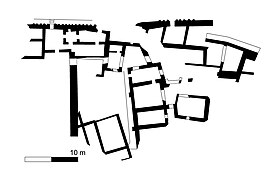

Plan of the palace remains. Period IV.1

-

Plan of Temple, Period IV

Periods V

[edit]

Period V was very poorly preserved due to the erosion of the excavation area. On the main hill, on the remains of the old palace, a large building was erected (called the Monument Massif by the excavators), with the old structures buried and partially preserved under the new and very massive building. A monumental ramp that led to a platform was still preserved during the excavations. This consisted of a number of rooms that could not be entered, so they had a pure support function. The actual building on this platform has completely disappeared. In other parts of the city there is also evidence of development during this period, but the remains are very poorly preserved. It is clear, however, that Mundigak continued to be an important city in Period V, but the remains of it have largely disappeared.[19] After that, the place appears to have been abandoned. After 2500 BCE there was no longer a city here. This is particularly noteworthy as there is no chronological overlap with the Indus culture.[20]

Periods VI and VII

[edit]No structural remains have been preserved from Period VI. In addition to fireplaces, there were primarily numerous ceramics that have similarities with that of the earlier layers. The excavator suspects that these remains came from nomads.[21] It seems that the population gave up their lifestyle in permanent settlements and moved to nomadism. This can also be observed in other places in Afghanistan and India. The last development is called Period VII. These are various agricultural storehouses, which probably date back to the 1st millennium BCE.

Indus Valley links

[edit]Mundigak has some material related to the Indus Valley civilization. This material consists in part of ceramic figurines of snakes and humped bulls, and other items, similar to those found at other Indus Valley sites.[22]

Pottery found at Mundigak had number of similarities with such material found at Kot Diji.[23] This material shows up at the earliest layer of Kot Diji.

Architecture

[edit]

Remains of a "palace" have been found in one mound. Another mound revealed a large "temple", indicating urban life.[22]

An extensive series of mounds marks the site of a town. The chronology is still uncertain, but it has tentatively been divided into seven main periods with many subdivisions. The main period seems to be Period IV, which saw a massive rebuilding after an earlier destruction. Both the "palace" and the "temple" and possibly the city walls as well date from this period. Another destruction layer and a marked ceramic change indicate a gap of abandonment between Periods IV and V, followed by a period of further building and construction of new monuments, including the "massive monument". Periods VI and VII saw only periodic occupation on a small scale.

Mundigak and Deh Morasi provide early developments in what may be now called religious activities. A white-washed, pillared large building with its door way outlined with red, dating around 3,000 BC is related to religious activities.[2]

Early houses were constructed at Mundigak (during Period I.4) in the form of tiny oblong cells with pressed earth walls. In the following layer (Period I.5) larger houses with square and oblong houses with sun dried bricks were found. Ovens for cooking and wells for water storage were found during later phases.[24]

Artifacts found

[edit]

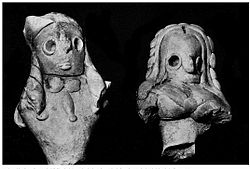

The finds include numerous terracotta figures, which often represent people, mostly women, but also men. There are also frequent depictions of cattle. In addition, in the remains of Period IV, the head of a limestone man's statue was found.[25] It is the only object that can be called a work of art in the narrower sense. The face is rather roughly worked. The eyes and eyebrows are heavily stylized. The man has short hair and a headband that ends in two falling strips of fabric on the back. Statues were also found sporadically in the Indus culture, in the oasis culture spread around the same time in the north and in Shahr-i Sukhta, which is also attributed to the Helmand culture. The statues show a man kneeling on the floor, often described as a priest-king. It has been suggested that Mundigak's head also belonged to such a figure,[26] but this cannot be proven.

Pottery is particularly important for small finds. Most of the ceramics are painted, some of them polychrome. Various decoration traditions can be proven that are also known from other places and thus help to locate Mundigak in the context of other cultures and thus also in time. The excavation report largely focuses on decorated forms, so the undecorated pottery is less well known. There were hand-formed vessels, but also those that were made on the potter's wheel. Periods I and II are dominated by simple, painted geometric patterns, often on the upper edge of bowls; in Period III the painting becomes more complex. There are still predominantly geometric patterns that belong to the so-called Quetta style. Others are painted in the style of the Nal culture or have similarities with ceramics of the Amri culture. In Period IV there are also isolated figurative representations, especially cattle.[27] Various clay chalices come from Period IV, decorated with rows of animals painted in black, but also with individual plants. A group of these chalices was found in room XXII in the palace. The goblets exposed there were intact.[28]

From Period IV there are two larger ceramic vessels with a sliding lid that may have served as mouse traps.[29] Comparable mouse traps are known from Mohenjo-Daro in the Indus Valley. The corresponding finds from Mundigak are probably several centuries older.[30]

Spinning whorls are from Period I.4. attested, of which there were two types: one is conical in shape and made of clay, the other is disc-shaped and carved from stone.[31] Stone vessels are attested in almost all layers.[32]

From Period I, level 2 onwards, bronze objects are attested. Initially, they are simple tools such as needles and weapons. However, the remains of a mirror also come from Period IV. An investigation showed that these artifacts were mostly made of bronze with a low tin content.[33] Five objects with iron elements from Period IV are noteworthy.[34] The iron always served as a decoration for bronze objects; there were no artifacts made entirely of iron.[35]

Apart from pottery and painted pottery, other artifacts found include crude humped bulls, human figures, shaft hole axes, adzes of bronze and terracotta drains.[22] Painting on pots include pictures of sacred fig leaves (ficus religiosa) and a tiger-like animal.[36] Several stone button seals were also found at Mundigak.[37] Disk Beads and faience barrel beads,[38] copper stamp seals, copper pins with spiral loops were also found.[39]

The female-looking human figurines (5 cm (2.0 in) in height) found at Mundigak are very similar to such figurines found at another archeological site in Afghanistan, Deh Morasi Ghundai (circa 3000 BCE).[2]

Collection:

- BIAS and DAFA – sherds;

- Kabul Museum and Musée Guimet – excavated material.

Field work:

- 1951-58 Casal, MAI – excavations.[40]

Finds in the Musée Guimet, mainly from Period IV

[edit]-

Stone vessels

-

Cup

-

Cup

-

Cup

-

Animal figures

-

Bull head

-

Seals

See also

[edit]- List of Indus Valley Civilization sites

- List of inventions and discoveries of the Indus Valley Civilization

- Hydraulic engineering of the Indus Valley Civilization

- Mehrgarh — archaeological site in Bolan near Quetta

- Sheri Khan Tarakai — archaeological site in Bannu

- Hadda — archaeological site in Nangarhar Province

- Surkh Kotal — archaeological site in Baghlan Province

- Mes Aynak — archaeological site in Logar Province

References

[edit]- ^ Casal, Jean Marie (1961): Fouilles de Mundigak, Paris

- ^ a b c "Afghanistan Prehistory". Archived from the original on February 18, 2012.

- ^ McIntosh, Jane. (2008) The Ancient Indus Valley, New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. Page 86.[1]

- ^ McIntosh, Jane. (2008) The Ancient Indus Valley, New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. Page 87.[2]

- ^ McIntosh, Jane. (2008) The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. Page 86.[3]

- ^ MSH Mondes, Service des Archives. "Fonds MAI1-MAI955 - Missions archéologiques des Indes et de l'Indus". Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ Casal, Jean-Marie (1954). "Quatre campagnes de fouilles à Mundigak 1951-1954". Arts Asiatiques. 1 (3): 163–178. ISSN 0004-3958.

- ^ Casal, Jean-Marie (1952). "Mundigak : un site de l'Âge de Bronze en Afghanistan". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 96 (3): 382–388. doi:10.3406/crai.1952.9959.

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 23–27.

- ^ Lyonnet, Bertille, and Nadezhda A. Dubova, (2020). "Questioning the Oxus Civilization or Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Culture (BMAC): An overview", in The World of Oxus Civilization, Routledge, p. 8, Table 1.1.

- ^ Jarrige, J.-F., A. Didier, and G. Quivron, (2011). "Shahr-i Sokhta and the Chronology of the Indo-Iranian Borderlands", in Paléorient 37 (2), p. 17: "...We agree with the links, which we ourselves often observed, between Shahr-i Sokhta I, II and III and Mundigak III and IV and between the sites of Balochistan and the Indus valley at the end of the 4th millennium and in the first half of the 3rd millennium BC..."

- ^ Schaffer, Jim G., and Cameron A. Petrie, (2019), "The development of a "Helmand Civilisation" south of the Hindu Kush", in Raymond Allchin, Warwick Ball, and Norman Hammond (eds.), The Archaeology of Afghanistan, From earliest Times to the Timurid Period, New Edition, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, ISBN 9780748699179, pp. 189–191.

- ^ Schaffer, Jim G., and Cameron A. Petrie, (2019), "The development of a "Helmand Civilisation" south of the Hindu Kush", in Raymond Allchin, Warwick Ball, and Norman Hammond (eds.), The Archaeology of Afghanistan, From earliest Times to the Timurid Period, New Edition, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, ISBN 9780748699179, pp. 166–173.

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 29–32, Figs. 6–7.

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 126–28, Figs. 49–50.

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 33–36.

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 126–28, Figs. 63–65.

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 79–81, Figs. 42.

- ^ Schaffer, Jim G., and Cameron A. Petrie, (2019), "The development of a "Helmand Civilisation" south of the Hindu Kush", in Raymond Allchin, Warwick Ball, and Norman Hammond (eds.), The Archaeology of Afghanistan, From earliest Times to the Timurid Period, New Edition, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, ISBN 9780748699179, pp. 187–189.

- ^ E. Cortesi, Maurizio, Tosi, A. Lazzari, Massimo Vidale: Cultural Relationships beyond the Iranian Plateau: The Helmand Civilization, Baluchistan and the Indus Valley in the 3rd Millennium BCE. In: Paléorient, 2008, Bd. 34, Nr. 2, pp. 26.

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c Ghosh, Amalananda (1990). An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology. ISBN 9004092641. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ McIntosh, Jane. (2008) The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. Page 75.[4]

- ^ Bridget and Raymond Allchin. The Birth of Indian Civilization. Penguin Books. 1968. Page 237

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 76–77, 255, Tables XLIII, XLIV; Victor Sarianidi: Die Kunst des alten Afghanistan. Architektur, Keramik, Siegel, Kunstwerke aus Stein und Metall. VCH, Acta Humaniora, Weinheim 1986, ISBN 3-527-17561-X, S. 113, Tables 28, 29 auf 117, Table 36 of pp. 124; Image of the head up, Harappa.com.

- ^ Massimo Vidale: A Priest King at Shahr-i Sokhta?, in: Archaeological Research in Asia 15 (2018), pp. 111

- ^ Schaffer, Jim G., and Cameron A. Petrie, (2019), "The development of a "Helmand Civilisation" south of the Hindu Kush", in Raymond Allchin, Warwick Ball, and Norman Hammond (eds.), The Archaeology of Afghanistan, From earliest Times to the Timurid Period, New Edition, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, ISBN 9780748699179, pp. 192–216.

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 182–184, Figs. 62–65, PL. XXXII.

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 145, Nrn. 314, 314a, pp. 197. Fig. 84.

- ^ E. Cortesi, Tosi, Lazzari, M. Vidale: Cultural Relationships beyond the Iranian Plateau: The Helmand Civilization, Baluchistan and the Indus Valley in the 3rd Millennium BCE, in: Paléorient, 2008, Bd. 32, Nr. 3, pp. 5–35; see also the website of Yves Traynard with a picture of the mousetrap that is exhibited today in the Musee Guimet.

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 232, Fig. 133.

- ^ Casal: Fouilles de Mundigak, pp. 233–234, Fig. 134.

- ^ Schaffer, Jim G., and Cameron A. Petrie, (2019), "The development of a "Helmand Civilisation" south of the Hindu Kush", in Raymond Allchin, Warwick Ball, and Norman Hammond (eds.), The Archaeology of Afghanistan, From earliest Times to the Timurid Period, New Edition, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, ISBN 9780748699179, pp. 218–221.

- ^ V. C. Pigott: The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World, Philadelphia 1999, ISBN 0-924171-34-0, p. 159.

- ^ Jonathan M. Kenoyer, Heather M.-L. Miller: Metal Technologies of the Indus Valley Tradition in Pakistan and Western India, V. C. Pigott (eds.): The archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World, Philadelphia: The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-0-924171-34-5, p. 121.

- ^ Bridget and Raymond Allchin. The Birth of Indian Civilization. Penguin Books.1968. Plate 5 B

- ^ Bridget and Raymond Allchin. (1982) The Rise of Civilisation in India and Pakistan. Page 139

- ^ Bridget and Raymond Allchin. (1982) The Rise of Civilisation in India and Pakistan. Page 202 [5]

- ^ Bridget and Raymond Allchin. (1982) The Rise of Civilisation in India and Pakistan. Page 232

- ^ Casal, Jean-Marie (1954). "Quatre campagnes de fouilles à Mundigak 1951-1954". Arts Asiatiques. 1 (3): 163–178. ISSN 0004-3958. JSTOR 43483921.

- Archaeological Gazetter of Afghanistan / Catalogue des Sites Archéologiques D'Afghanistan, Volume I, Warwick Ball, Editions Recherche sur les civilisations, Paris, 1982.