Women in Iraq

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 76 (2020)[1] |

| Women in parliament | 26.4% (2021)[2] |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 22.0% (2010) |

| Women in labour force | 13.885% (2023)[3] |

| Gender Inequality Index[4] | |

| Value | 0.577 (2019) |

| Rank | 146th out of 162 |

| Global Gender Gap Index[5] | |

| Value | 0.535 (2021) |

| Rank | 154th out of 156 |

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

|

The status of women in Iraq has been affected by wars, Islamic law, the Constitution of Iraq, cultural traditions, and secularism. Hundreds of thousands of Iraqi women are war widows, and Women's rights organizations struggle against harassment and intimidation while they work to promote improvements to women's status in the law, in education, the workplace, and many other spheres of Iraqi life. Abusive practices such as honor killings and forced marriages persist.

Historical background

[edit]Middle ages

[edit]As a part of their conquest, the Iamas successfully defeated the Persians during the seventh century. Doreen Ingrams, the author of The Awakened: Women in Iraq, stated it was a time when women's help was needed. In particular, a woman called Amina bint Qais "at the age of seventeen was the youngest woman to lead a medical team in one of these early battles."[6]: 21 After their victory, the Arabs that began ruling Mesopotamia named that country Iraq. During the Abbasid Caliphate, it was common for upper-class men to own women as sex slaves,[7] with the Abbasid harem as role model, and a number of enslaved women (qiyan) were known for their wit and charm: “many of the well-known women of the time were slave girls who had been trained from childhood in music, dancing and poetry".[6]: 22 A story featured in One Thousand and One Nights involves Tawaddud, “a slave girl who was said to have been bought at great cost by Harun al-Rashid because she had passed her examinations by the most eminent scholars in astronomy, medicine, law, philosophy, music, history, Arabic grammar, literature, theology and chess”.[8] It was rarer for free women to achieve prominence in Abbasid society,[7] though some notable women did exist. Among the most prominent female figures was a scholar named Shuhda, who was known as “the Pride of Women” during the twelfth century in Baghdad.

In 1258, Baghdad was attacked and captured by the Mongols.[9] With the departure of the Mongols a succession of Persian rivalries followed until 1553, when the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman captured Baghdad and its provinces, which became parts of the Turkish empire. Ingrams states that Turks “had inflexible rules concerning women", leading to a decline in the status of women.[6]: 25 In contrast, Beatrice Forbes Manz states that women were granted a relatively high and public position in Turkic and Mongol societies, and several women in the Turkic dynasties ruling Iraq, like the Timurid Empire, achieved political importance.[10]

Ottoman Iraq

[edit]Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I, Britain was given the Mandate for administering Iraq by the League of Nations and therefore a new era began in Iraq under British rule.[11] The Iraqi Revolt in 1920 included women who participated against British oppression.[12]

Kingdom of Iraq

[edit]The Iraqi women's movement started with the foundation of the Women's Awakening Club, and the first women's magazine, Layla, was first published in 1923, by journalist Paulina Hassoun.[13]

In 1932, Iraq was declared independent and in 1946 was a founding member of the United Nations. Instability was dominating the region until 1968 when the Ba’ath Party took control over the President Al Bakr and Iraq began to enjoy a period of stability.[14] Majda al-Haidari, wife of Raouf al-Chadirchi, has sometimes been said to be the first woman in Baghdad to have appeared unveiled in the 1930s,[15] but the Communist Amina al-Rahal, sister of Husain al-Rahal, have also been named as the first unveiled role model in Baghdad.[16] In the 1930s and 1940s, female College students gradually started to appear unveiled,[15] and most upper- and middle class urban women in Iraq were said to be unveiled by 1963.[17]

A breakthrough in the issue of women's suffrage came in 1958. During the Arab Union of Iraq-Jordan, the Iraqi Constitution was set, in March 1958, to be amended to include women's suffrage later that year, but the matter became moot when the monarchy was abolished in July that year.[18] An unnamed MP to the newspaper al-Hawadith that he could never run against a female candidate, since if he lost he would have lost to a woman, which would have been dishonorable, and if he won, he would only have won over a woman; he claimed many male MPs felt the same, and that voters would also feel dishonored by being represented and ruled by a woman.[19] The MP Tawfq al-Mukhtar commented to a reporter: "Friends, women's rights bother me a lot, and anybody who condemns or criticizes them gives me great pleasure"; he added that he would withdraw if he was put against a female candidate, and he was one of four MPs to vote against the proposed amendment of March 1958.[20]

Baathist regime

[edit]In Ba'athist Iraq (1968-2003), the Secular Socialist Baath Party women were officially stated to be equal to men, and urban women were normally unveiled.[21][22][23]

In 1970, equal rights for women were enshrined in Iraq's Constitution, including the right to vote, run for political office, access education and own property.[24] Article 19 of the Iraqi Provisional Constitution of 1970 granted all Iraqi citizens equal before the law regardless of sex, blood, language, social origin or religion, and the state women's umbrella organization General Foundation of Iraqi Women (GFIW) of 1972 guaranteed women's full equal rights in the professional and educational sphere, prevented all discrimination and recognized women's political participation in principle.[25]

Saddam Hussein succeeded Al Bakr as President in 1979. In 1980 full suffrage was granted and women were given the right to vote and be elected to political office.[26][27] The suffrage reform was granted when the new Iraq National Assembly was formed before the 1980s Elections, and 16 of 250 seats where filled by women.[28]

After the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, there was a surge in threats and harassment of unveiled women, and the use of hijab became common in Iraq.[29]

Education

[edit]Iraq established an education system in 1921 and by the 1970s education became public and free at all levels.[30] Despite education being free until 1970, women had lower literacy rates than men on average.[31] Girls possessed low literacy rates because there were not enough schools to instruct them even though the Iraqi government made education mandatory for everyone.[31] Furthermore, women were required to have completed a basic education to vote in 1957.[31] A census conducted during this time showed that approximately one percent of women could legally vote.[31] This highlights a large disparity in not only women who are educated, but those who are able to vote.

During the 1970s and 1980s, despite Saddam Hussein attempting to use higher education as a form of propaganda, the overall illiteracy rate dropped until the Iran-Iraq War.[32] The progression of women's education has been hampered by the Iran-Iraq War, Gulf War, and the 2003 Iraq War. Throughout these wars, there have been several authoritarian leaders whose government policies negatively affected those in higher education. One those changes in regards to government policy is the severe lack of government funding to those in universities following the costly Iran-Iraq War. Government spending dropped from $620 before the Iran-Iraq War to $47; This decline happened slowly over time as Iraq as a country was suffering from economic challenges and put its budget elsewhere.[33] Consequently, this caused the enrollment rate to drop by 10% and the dropout rate by 20%, of which 31% were females compared to that of 18% of males; There were less women with upper-level jobs since they could not afford them in the first place.[33]

Women's overall literacy rate continued to decline well after the Iran-Iraq War, moreover this decline was more pronounced in the Southern rural provinces where obtaining an education was already difficult to begin with.[34] Overall attendance during the Iraq War was 68% amongst young girls compared to 82% of young boys, while girls in rural areas had a mere 25% attendance rate.[35][34] The wars forced women to work in agriculture rather than pursue a degree as necessary items such as food and water started to become more scarce and expensive.[32] Violence against women, such as rape, became more commonplace during the war period and was another reason as to why women did not pursue education.[32] Wartime violence was less pronounced in the Northern provinces of Iraq since less conflicts occurred in the region, which was under influence by Kurdish leaders.[35] During the Gulf War, the economic situation became so dire that women could not afford transportation fares to go to school in the first place.[32] Furthermore, some of the universities that did operate required women to wear the hijab; Those who didn't were subject to discrimination or sexual harassment by their male peers.[36] These students had to end their education abruptly and take care of their children instead.[32] Outside of wartime violence, there was a common perception that marriage provided better economic security for women than attending school.[35] The reliance on early marriages and the stress and grief caused by the wars on women left them incapable of making positive changes in the country via a political position.[35] Furthermore, the many years of education that women lost because of the wars created more wage and gender inequality for many years to come.[35]

The gender gap with regard to Iraq's literacy rate is narrowing. Overall, 26% of Iraqi women are illiterate, and 11% of Iraqi men. For youth aged 15–24 years, the literacy rate is 80% for young women, and 85% for young men.[37] Girls are less likely than boys to continue their education beyond the primary level, and their enrollment numbers drop sharply after that. Education levels attained by Iraqi women and men in 2007 were:[38]

| Level of education | Female (%) | Male (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | 28.2 | 30.2 | 29.2 |

| Secondary | 9.6 | 13.7 | 11.6 |

| Preparatory (upper secondary) | 5.0 | 8.9 | 6.9 |

| Diploma | 3.8 | 5.4 | 4.6 |

| Higher | 3.1 | 5.6 | 4.4 |

Women's rights

[edit]With an estimated population of 22,675,617 women, Iraq is a male dominated society.[39]

On International Women's Day, 8 March 2011, a coalition of 17 Iraqi women's rights groups formed the National Network to Combat Violence Against Women in Iraq.[40]

The Organization of Women's Freedom in Iraq (OWFI) is another Non-governmental organization committed to the defense of women's rights in Iraq. It has been very active in Iraq for several years, with thousands of members, and it is the Iraqi women's rights organization with the largest international profile. It was founded in June 2003 by Yanar Mohammed, Nasik Ahmad and Nadia Mahmood. It defends full social equality between women and men and secularism, and fights against Islamic fundamentalism and the American occupation of Iraq. Its president is Yanar Mohammed.

OWFI operates multiple shelters across Iraq for victims of domestic abuse and sexual violence, and it provides critical support to vulnerable minorities. The organization has garnered significant international support and recognition, which underscores its extensive network and influence both within and outside Iraq.[41] Notably, OWFI'S shelters have served as a refuge for women escaping honor killings and trafficking, offering them not just a safe place but also vocational training and psychological support.[41]

After the 2003 invasion, the government tried to remove the Personal Law Code, which is the basis for women's legal rights in Iraq. However feminist mobilization blocked this attempt and the law was reinstated.[42] This victory highlighted the growing influence of women's rights organizations like OWFI in creating national policies.

OWFI originated with the Organisation indépendante des femmes, active in Kurdistan from 1992 to 2003 despite government and religious oppression, and the Coalition de défense des droits des femmes irakiennes, founded in 1998 by Iraqi women in exile. OWFI concentrates its activities on the fight against sharia law, against abduction and murder of women and against honour killings. Thousands of members strong, it has at its disposal a network of support from outside Iraq, notably from the United States. It also has members in Great Britain, Canada, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Norway, Finland, and Denmark. Its activists and its directors have many times been the object of death threats from Islamic organizations.

The circumstances resulting from the Gulf War and then the 1991 Iraqi uprisings, gave the Kurdish region of Iraq an essentially autonomous situation for a period, despite the conflicts between zones controlled by the largest nationalist parties. This allowed the development of some claims to women's rights, which in turn influenced some of the women who would become active in founding OWFI. During this period, Kurdish women activists began to demand legal reforms, better education, and protection from violence, laying the groundwork for future national movements.[41]

OWFI's efforts have been recognized globally. In 2014, the organization received the Rafto prize for Human Rights for its effort to protect women's rights in a war-torn society.[43] This recognition has helped OWFI to secure funding and support from international NGOs and human rights groups, enabling it to expand its programs and services.

The founding statement of OWFI contains a mandate in six points:

- To put in place a humanist law founded on equality and the assurance of the greatest freedom for women, and to abolish all forms of discriminatory laws;

- To separate religion from the government and education;

- To put an end to all forms of violence against women and honour killings, and to push for punishment for the murderers of women;

- To abolish mandatory wearing of veils, the veil for children and to protect freedom of dress;

- To put in place the equal participation of women and men in all social, economic, administrative and political spheres, at every level;

- To abolish gender segregation in schools at all levels.

Some militant women's rights advocates in Iraq, who seek to establish a dialogue with Islamist women, maintain a distance from the radical feminism and secularism of OWFI.[45]

Women's rights in Iraqi Kurdistan

[edit]Some reported issues related to women in Kurdish society include genital mutilation,[46] honor killings,[47] domestic violence,[48] female infanticide[48] and polygamy.[49] Majority of reports have come from Iraq where the Kurdish and Iraqi population have been poorly educated and illiteracy is still a big problem among citizens. However, some reported issues have not been taken seriously, because all reported issues are common among the populations with whom they live.

Some Kurds in small populated areas, especially uneducated Kurds are organized in patrilineal clans, there is patriarchal control of marriage and property, women are generally treated in many ways like property.[50][51] Rural Kurdish women are often barred from making their own decisions regarding sexuality or husbands. Arranged marriages, and in some places child marriages, are common.[50][51][52][page needed] Some Kurdish men, especially religious Kurds, also practice polygamy.[52][page needed] However, polygamy has almost disappeared from Kurdish culture,[citation needed] especially in Syria after Rojava made it illegal. Some Kurdish women from uneducated, religious and poor families who took their own decisions with marriage or had affairs have become victims of violence, including beatings, honor killings and in extreme cases pouring acid on faces (very rare) (Kurdish Women's Rights Watch 2007).[51][52][page needed][53] Kurds generally see having large families as the ideal.[50]

Women's rights activists have said that after the elections in 1992, only five of the 105 elected members of parliament were women, and that women's initiatives were even actively opposed by Kurdish male politicians.[54] Women's rights activist Tanya Gilly Khailany, who was a member of the Iraqi Parliament between 2006 – 2010, pushed for the legislation of 25 per cent quota for women in Iraqi provincial councils.[55]

Honor killings and other forms of violence against women have increased since the creation of Iraqi Kurdistan, and "both the KDP and PUK claimed that women's oppression, including ‘honor killings’, are part of Kurdish ‘tribal and Islamic culture’".[54] New laws against honor killing and polygamy were introduced in Iraqi Kurdistan, however it was noted by Amnesty International that the prosecution of honor killings remains low, and the implementation of the anti-polygamy resolution (in the PUK-controlled areas) has not been consistent.[54] On the other hand, women rights activists also had some successes in Iraqi Kurdistan, and it was claimed that "the rise of conservative nationalist forces and the women's movement are two sides of the same coin of Kurdish nationalism."[54]

Scholars like Mojab (1996) and Amir Hassanpour (2001) have argued that the patriarchal system in Kurdish regions has been as strong as in other Middle Eastern regions.[52]: 227 [56][57] In 1996, Mojab claimed that the Iraqi Kurdish nationalist movement "discourages any manifestation of womanhood or political demands for gender equality."[56][58][59][60]

In 2001, Persian researcher Amir Hassanpour claimed that "linguistic, discursive, and symbolic violence against women is ubiquitous" in the Kurdish language, matched by various forms of physical and emotional violence.[52][page needed][58]

In 2005, Marjorie P. Lasky from CODEPINK claimed that since the PUK and KDP parties took power in Northern Iraq 1991, "hundreds of women were murdered in honor killings for not wearing hijab and girls could not attend school", and both parties have “continued attempts to suppress the women's organizations”. Marjorie P. Lasky also said that U.S. military personnel have committed crimes of sexual abuse and physical assault against women and they are one of the reasons why women rights have worsened in Iraq.[61] The honor killing and self-immolation condoned or tolerated by the Kurdish administration in Iraqi Kurdistan has been labeled as "gendercide" by Mojab (2003).[54][62] Lasky concluded: "More widely reported are the Iraqi Kurdish nationalist parties’ "disregard of women's issues and their attempts to suppress women's organizations".[58]

Women's suffrage

[edit]Full women's suffrage was introduced in Iraq in 1980.

The campaign for women's suffrage started in the 1920s. The women's movement in Iraq organized in 1923 with the Nahda al-Nisa (Women's Awakening Club), lead by Asma al-Zahawi and with elite women such as Naima a-Said, and Fakhriyya al-Askari among their members.[63] King Faysal himself had supported women's suffrage during his prior short tenure as king in Syria. Feminists such as Mary Wazir and Paulina Hasun raised the issue in the 1920s.[64] Paulina Hassan published the first Iraqi women's magazine, Layla, in 1923-1925, followed by a number of women's magazines in the 1930s and 1940s that voiced feminist demands.[65] When the Constituent Assembly of Iraq was inaugurated in 1924, Paulina Hassun appealed to the Assembly that women should not be excluded from political participation in the new nation, and one of the members, Amjad al-Umari, unsuccesfully proposed that the word "male" be erased from the Electoral Law to include women in it.[66]

The Women's suffrage reform was primarily supported by the opposition parties, notably the Iraq Communist Party.[67] During the 1930s, the Communist ICP and the leftist al-Ahali supported women's suffrage.[68] Even those supporting the reform, however, often did so with the reservation that woman should reach a higher level of education before they were ready for it.[69]

The Iraqi monarchy prioritized foreign policy rather than internal issues and showed little enthusiasm to adress the issue of women's suffrage.[70] The monarchy was careful to avoid alienating conservative and religious circles, who considered women's suffrage as imcompatible with the "nature" of women, the proper social order and gender hierarchies, and women's suffrage was not given refused serious consideration.[71] Both the Sunni and Shia clergy rejected women's suffrage as being in opposition to the natural roles of gender, as the "joke of the day", an attack on the law of nature and the proper way of life, since women were the weaker sex and "lesser persons" similar to children.[72] When women's suffrage in Syria was introduced in 1949, MP Farhan al-Irs of al-Amara commented: "Women are shameful. How could they possibly sit with men?"[73]

In 1951 a motion to include women in the Electoral Law was rejected in the Chamber of Deputies.[74] During the discussion to change the electoral law to include women's suffrage in March-April 1951, the MP Abd al-Abbas of Diwaniyya oposed suffrage as this would contradict Islamic sex segregation, as elected women MP would then sit among male MPs in the Chamber of Deputies: "Is this not forbidden? Are we not all of Islam?"[75]

An electoral decree in December 1952 provided direct elections but did not include women.[76] A Sunni scholar published an article in the paper al-Sijill in October 1952 named "The Crime of Equality Between Men and Women": as an imam and khatib of the mosques of Baghdad and scholar of the al-Azhar University, he stated that women's suffrage was a plot against Islam and contrary to Quranic verses which delineated gender hierarchies that made women in politics incompatible.[77]

A number of women's organization was founded in the 1940s and 1950s that campaigned for women's rights including suffrage, notably the Iraqi Union for Women's Rights (1952).[78] Naziha al-Dulaimi of the League for Defence of Women's Rights (Iraqi Women's League), which gathered 42,000 members, campaigned for gender equality (including suffrage), organized educational programs, provided social services, established 78 literacy centers, and drafted the 1959 Personal Status Law, which was accepted and introduced by the Government.[79] In the 1950s the Iraqi Women's Union petitioned senior state figures including the prime minister and wrote articles in the press.[80]

A Week of Women's Rights was launched in October 1953 by Iraqi Women's Union suffrage, who arranged a sumposium and voiced their demand in radio programs and articles in the press to campaigned for women's suffrage.[81] As a response, the Islamic clergy launched a Week of Virtue and called for a general strike against women's suffrage and called for women to "stay at home" since women's suffrage was against Islam.[82] During the Week of Virtue, the Sunni Nihal al-Zahawi, daughter of Amjad al-Zahawi, head of the Muslim Sisters Society (Jamiyyat al-Aukht al-Muslima), spoke on the radio against women's suffrage: she described the suffragists as women who revolted against the very Islam that gave them rights, and that women's suffrage was lamentable since it broke sex segregation and resulted in gender mixing, which was an unrestricted liberty that broke the rules of against islam.[83]

A breakthrough came in 1958. During the Arab Union of Iraq-Jordan, the Iraqi Constitution was set, in March 1958, to be amended to include women's suffrage later that year, but the matter became moot when the monarchy was abolished in July that year.[84] An unnamed MP to the newspaper al-Hawadith that he could never run against a female candidate, since if he lost he would have lost to a woman, which would have been disonorable, and if he won, he would only have won over a woman; he claimed many male MPs felt the same, and that voters would also feel dishonored by being represented and ruled by a woman.[85] The MP Tawfq al-Mukhtar commented to a reporter: "Friends, women's rights bother me a lot, and anybody who condemns or criticizes them gives me great pleasure"; he added that he would withdraw if he was put against a female candidate, and he was one of four MPs to vote against the proposed amendment of March 1958.[86]

In 1958 the Iraqi Monarchy was replaced by the Baathis regime. The early Baathist regime saw women's emancipation in many aspects, with urban liberal modernist women enjoying professional and educational equality and appearing unveiled.[87] The Baathist Party supported women's rights by principle, though it initially focused in expanding women's educational and professional rights rather than their political rights.[88] Article 19 of the Iraqi Provisional Constitution of 1970 granted all Iraqi citizens equal before the law regardless of sex, blood, language, social origin or religion, and the state women's umbrella organization General Foundation of Iraqi Women (GFIW) of 1972 guaranteed women's full equal rights in the professional and educational sphere, prevented all discrimination and recognized women's political participation in principle.[89] However, while women's rights progressed in other aspects, the political rights was delayed. The regime was unstable and saw four regime changes in the 1960s.[90]

In 1980 full suffrage was granted and women were given the right to vote and be elected to political office.[91][92] The suffrage reform was granted when the new Iraq National Assembly was formed before the 1980s Elections, and 16 of 250 seats where filled by women.[93]

Marriage

[edit]By law, a woman has to be eighteen years or older to get married. Marriage and family are necessities for economic needs, social control and mutual protection within the family.

Divorce is a very common practice in Iraq.[94]

Legal system

[edit]The Iraqi Constitution of 2005 states that Islam is the main source of legislation and laws must not contradict Islamic provisions. The family law is discriminatory towards women, particularly with regard to divorce, child custody, and inheritance. In a court of law, a woman's testimony is worth in some cases half of that of a man, and in some cases it is equal.[95]

In March 2008 an Iraqi 17-year-old girl was violently murdered by her father and two older brothers for becoming friendly with a British soldier. When her mother ran away out of defiance, she was found dead on her street, shot in the head twice. The father was released after two hours of questioning from the Iraqi police force and was neither charged nor tried with the murder of his daughter, although he had confessed to killing her.[96]

Sharia law

[edit]Islam is the official religion of Iraq with about 97% of the population practice this religion.[97]

On January 29, 2004, the interim Iraqi government, supported by the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq and despite the strong opposition of the American Administrator Paul Bremer, launched Resolution 137 which introduced sharia law in the "law on personal civil status", which since 1958 established rights and freedoms for Iraqi women. This resolution permitted very different interpretations from the law of 1958 on the part of religious communities. It opened an additional breach in the civil law and risked exacerbating inter-religious tensions in Iraq.[98] In a statement, OWFI affirmed:

Iraq is a secular society. Women and men in Iraq never imagined that they would defeat Ba'athist Fascism only to have it replaced with an Islamic dictatorship.[99]

Despite its reputation for being relatively secular, sharia law was never totally absent from Iraq before 2003. The "law on personal civil status" provided that, in the case that it was not expressly forbidden in the law, it would be sharia law that would prevail.[100] A coalition of 85 women's organizations, through means of international communication, launched a protest movement.[100] One month later, on January 29, 2004, the resolution was withdrawn.[101]

Beginning in September 2004, OWFI launched a new campaign against the forced wearing of the veil being enforced by Islamic militias, notably in the universities.[102]

In 2005, there was once again debate over the new constitution, which considered Islam as one of the sources of Iraqi law. Yanar Mohammed wrote:[103]

The outline of the constitution proposes, in article 14, the repeal of existing law and to refer merely to family law, in concordance with Islamic sharia law and other religious codes in Iraq. In other words, it makes women vulnerable to all forms of inequality and social discrimination. and makes them second class citizens, lesser human beings

For the same reasons, OWFI denounced the 2005 elections, dominated by parties hostile to women's rights.[104]

Women's groups also denounce "pleasure marriages", based on a practise commonly believed to be founded on Islamic law, which was revived during the occupation of Iraq: it authorizes a man to marry a woman, through a money gift, for a determined period of time. In most cases, groups such as OWFI charge, it provides a legal cover for prostitution.[105]

Crimes against women

[edit]Female genital mutilation

[edit]

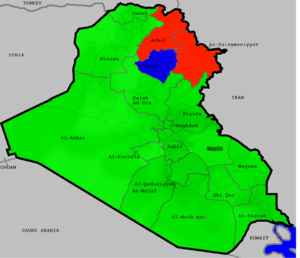

Female genital mutilation (FGM) was an accepted part of Sorani speaking Kurdish culture in Iraq, including Erbil and Sulaymaniyah.[106] A 2011 Kurdish law criminalized FGM practice in Iraqi Kurdistan and law was accepted four years later.[48][107][108] MICS reported in 2011 that in Iraq, FGM was found mostly among the Kurdish areas in Erbil, Sulaymaniyah and Kirkuk, giving the country a national prevalence of eight percent. However, other Kurdish areas like Dohuk and some parts of Ninewa were almost free from FGM.[109][110]

In 2014, a small survey of 827 households conducted in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah assessed a 58.5% prevalence of FGM in both cities. According to the same survey, FGM has declined in recent years.[110][111][112] In 2016, the studies showed that there is a trend of general decline of FGM among those who practiced it before. Kurdish human rights organizations have reported several times that FGM is not a part of Kurdish culture and authorities aren't doing enough to stop it completely.[113]

According to a 2008 report in The Washington Post, the Kurdistan region of Iraq is one of the few places in the world where female genital mutilation had been rampant.[114] According to one study carried out in 2008, approximately 60% of all women in Kurdish areas of northern Iraq had been mutilated.[114] It was claimed that at least one Kurdish territory, female genital mutilation had occurred among 95% of women.[114] The Kurdistan Region has strengthened its laws regarding violence against women in general and female genital mutilation in particular,[48] and is now considered to be an anti-FGM model for other countries to follow.[115]

Female genital mutilation was prevalent in Iraqi Kurdistan. In 2010, WADI published a study that 72% of all Kurdish women and girl were circumcised that year. Two years later, a similar study was conducted in the province of Kirkuk with findings of 38% FGM prevalence giving evidence to the assumption that FGM was not only practiced by the Kurdish population but also existed in central Iraq. According to the research, FGM is most common among Sunni Muslims, but is also practiced by Shi’ites and Kakeys, while Christians and Yezidi don't seem to practice it in northern Iraq.[116] In Erbil Governorate and Suleymaniya Type I FGM was common; while in Garmyan and New Kirkuk, Type II and III FGM were common.[117][118] There was no law against FGM in Iraq, but in 2007 a draft legislation condemning the practice was submitted to the Regional Parliament, but was not passed.[119] A field report by Iraqi group PANA Center, published in 2012, shows 38% of women in Kirkuk and its surrounding districts areas had undergone female circumcision. Of those circumcised, 65% were Kurds, 26% Arabs and rest Turkmen. On the level of religious and sectarian affiliation, 41% were Sunnis, 23% Shiites, rest Kaka’is, and none Christians or Chaldeans.[120] A 2013 report finds FGM prevalence rate of 59% based on clinical examination of about 2000 Iraqi Kurdish women; FGM found were Type I, and 60% of the mutilation were performed to girls in 4–7 year age group.[110]

Female genital mutilation is prevalent in Iraqi Kurdistan, with an FGM rate of 72% according to the 2010 WADI report[116] for the entire region and exceeding 80% in Garmyan and New Kirkuk. In Erbil Governorate and Suleymaniya Type I FGM is common; while in Garmyan and New Kirkuk, Type II and III FGM are common.[117][118] There was no law against FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan, but in 2007 a draft legislation condemning the practice was submitted to the Regional Parliament, but was not passed.[119] A 2011 Kurdish law criminalized FGM practice in Iraqi Kurdistan,[121] however this law is not being enforced.[108] A field report by Iraqi group PANA Center, published in 2012, shows 38% of women in Kirkuk and its surrounding districts areas had undergone female circumcision. Of those circumcised, 65% were Kurds, 26% Arabs and rest Turkmen. On the level of religious and sectarian affiliation, 41% were Sunnis, 23% Shiites, rest Kaka’is, and none Christians or Chaldeans.[120] A 2013 report finds FGM prevalence rate of 59% based on clinical examination of about 2000 Iraqi Kurdish women; FGM found were Type I, and 60% of the mutilation were performed to girls in 4–7 year age group.[110]

Honour crimes

[edit]In 2008 the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) has stated that honor killings are a serious concern in Iraq, particularly in Iraqi Kurdistan.[122] The Free Women's Organization of Kurdistan (FWOK) released a statement on International Women's Day 2015 noting that "6,082 women were killed or forced to commit suicide during the past year in Iraqi Kurdistan, which is almost equal to the number of the Peshmerga martyred fighting Islamic State (IS)," and that a large number of women were victims of honor killings or enforced suicide – mostly self-immolation or hanging.[123]

About 500 honour killings per year are reported in hospitals in Iraqi Kurdistan, although real numbers are likely much higher.[124] It is speculated that alone in Erbil there is one honour killing per day.[125] The UNAMI reported that at least 534 honour killings occurred between January and April 2006 in the Kurdish Governorates.[126][127] It is claimed that many deaths are reported as "female suicides" in order to conceal honour-related crimes.[126][128] Aso Kamal of the Doaa Network Against Violence claimed that they have estimated that there were more than 12,000 honor killings in Iraqi Kurdistan from 1991 to 2007. He also said that the government figures are much lower, and show a decline in recent years, and Kurdish law has mandated since 2008 that an honor killing be treated like any other murder.[129]

Attitudes towards domestic violence are ambivalent even among women. A UNICEF survey of adolescent girls aged 15–19, covering the years 2002–2009, asked them if they think that a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife under certain circumstances; 57% responded yes.[37]

Under the Criminal Code of Iraq, honor killings can only be punished with a maximum of three years. According to paragraph 409 "Any person who surprises his wife in the act of adultery or finds his girlfriend in bed with her lover and kills them immediately or one of them or assaults one of them so that he or she dies or is left permanently disabled is punishable by a period of detention not exceeding 3 years. It is not permissible to exercise the right of legal defence against any person who uses this excuse nor do the rules of aggravating circumstance apply against him".[130] In addition to this, a husband also has a legal right to "punish" his wife: paragraph 41 states that there is no crime if an act is committed while exercising a legal right. Examples of legal rights include: "The punishment of a wife by her husband, the disciplining by parents and teachers of children under their authority within certain limits prescribed by law or by custom".[130]

Information supplied by OWFI on the resurgence of honour crimes since 2003 was included in the September 2006 report by the UN Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI).[131]

Shelters

[edit]OWFI created shelters in Baghdad, Kirkuk, Erbil and Nassiriya for women and couples whose families have threatened them with honour crimes.[132] The location of shelters was kept secret and they were under permanent guard. A crisis phone line number was available in each issue of 'al-Moussawat. An "underground railroad" was put in place, with the help of the American association Madre, to allow some women to clandestinely escape the country.[132] Several other organizations from abroad assisted this initiative.[102][133][134]

Since the end of 2007, the shelters, determined to be too dangerous for the residents, were closed and many of the women were accommodated in host families. The operation costs OWFI around $60,000 per year.[135]

Forced prostitution, abductions and killings of women

[edit]Beginning in August 2003, OWFI organized a protest to attract attention to the rapid growth in rapes and abductions.[102] A letter sent by OWFI to Paul Bremer, in charge of the American administration in Iraq, on the question of violence against women, remained unanswered.[136]

An inquiry was initiated by OWFI to examine abductions and killings of women. Yanar Mohammed comes to the following conclusion:

According to our estimates, no fewer than 30 women were executed by the militias in Baghdad and in the suburbs. During the first ten days of November 2007, more than 150 unclaimed women's corpses, most of them decapitated, mutilated, or having evidence of extreme torture, were processed through the Bagdad morgue.[132]

For OWFI, these deaths are linked to honour crimes,[137] but in this case, in a new form, since the killings are taken beyond the family circle to become the business of paramilitary groups.

Beginning in 2006, OWFI initiated an inquiry into the link between widespread abductions of women and prostitution networks. Activists for women's rights in Iraq have mapped and studied prostitution in their country to understand how it functions and how trafficking spreads, showing that the majority of prostitutes are minors and that the trafficking networks extend throughout the Middle East. This campaign of enquiry, publicized by an interview on the channel MBC in May 2009, was denounced by the pro-government channel Al-Iraqia, which held that it constituted a "humiliation for Iraqi women".[138] Indeed, shortly before his resignation, Minister of Women's Affairs Nawal al-Samarraie had declared that the traffic in prostitution was limited and that the young women were involved voluntarily, which Yanar Mohammed had denounced.[139]

The Iraqi Kurdistan region has reportedly received "women and children trafficked from the rest of Iraq for prostitution".[140] Criminal gangs have prostituted girls from outside of the Iraqi Kurdistan Region in the provinces of Erbil, Dahuk, and Sulaymaniyah.[141] NGOs have alleged that some personnel from the Kurdistan Regional Government's Asayish internal security forces have facilitated prostitution in Syrian refugee camps in Iraqi Kurdistan.[142] Iraqi women were sold into “temporary marriages” and Syrian girls from refugee camps in Iraqi Kurdistan were forced into early or “temporary marriages”, and it was alleged that KRG authorities ignored such cases.[142][143]

On October 2, 2020, a UN special rapporteur urged the Iraqi authorities to investigate the murder of a woman human rights defender, and the attempted killing of another, targeted “simply because they are women”.[144]

Abuse of women since the invasion

[edit]The many conflicts in Iraq came with an increase of oppression against women. Prior to the arrival of forces in Iraq in 1991, Iraqi women were free to wear whatever they liked and go wherever they chose.[145]: 105–107 The Iraqi constitution of 1970 gave women equality and liberty in the Muslim world, but since the invasion, women's rights have fallen to the lowest in Iraqi history.[145]: 105–107

Since the invasion in 2003 "Iraqi women have been brutally attacked, kidnapped and intimidated from participating in the Iraqi society".[146] Yanar Mohammed, an Iraqi feminist, "asserts unequivocally that war and occupation have cost Iraqi women their legal standing and their everyday freedom of dress and movement".[147] She continues by arguing that "The first losers in all these were women".[147]

Arising from their fear of being raped and harassed, women have to wear not only the veil, but must also to wear chador in order not to attract attention. In an online edition of The Guardian, Mark Lattiner reports that despite promises and hopes given to the Iraqi population that their lives were going to improve, Iraqi women's lives "have become immeasurably worse, with rapes, burnings and murders [now] as a daily occurrence."[148]

Yazidi women

[edit]The invasion by the Islamic State in 2014 further exacerbated gender violence and discrimination against women in Iraq, limiting women's movement and opportunities. The Yazidi women have been severely affected by ISIS conflicts and the Yazidi genocide in 2014. The Yazidis, a Kurdish minority, in northern Iraq and western Kurdistan have beceome victims of ISIS violence. The rise of ISIS in 2014 led to human rights violations, including a 2014 attack on Mount Sinjar that resulted in about 3,100 deaths and 6,800 abductions.[149] Women and girls were targeted for abduction and sexual violence. Approximately 300,000 Yazidis have been displaced in Kurdistan, mainly in refugee camps, with many still missing. Displaced Yazidis suffer from high levels of physical and mental health issues, with women experiencing especially high rates of trauma, PTSD, and depression due to war-related and gender-based violence.[149]

Women's prisons

[edit]OWFI has set up an observation group of activists, directed by Dalal Jumaa, which focuses its action on the defense of the rights of women in prison and in police detention. It has notably obtained authorization to regularly visit the Khadidimya prison, in Baghdad, and to denounce the detention conditions: rapes during interrogations, poor treatment, and the presence of children in the cells. OWFI has taken part in negotiations with the municipality of Bagdad to open a daycare in proximity to the prison.[150]

In 2009, OWFI was alerted to the situation of 11 women condemned to death, detained in this prison, after the execution of one among them.[151] In 2010, OWFI observers met young girls aged 12 years, expelled from Saudi Arabia for prostitution and imprisoned in Iraq.[138] In February 2014 Human Rights Watch released a 105-page report 'No One is Safe' alleging there are thousands of Iraqi women in jails being held without charge, that are being routinely tortured, beaten, and raped.[152]

1990 Iraq Sanctions

[edit]The United Nations implemention of strict economic sanctions on trade to and from on Iraq in 1990, following Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, impacted women's lives in Iraq more than men.[153] The gendered impact of the international sanctions on Iraq in 1990 significantly increased the challenges faced by women in all fields. In the labor market, sanctions severely restricted economic prospects. This led to a dramatic decline in women's labor participation and employment. Women's positions and jobs were undermined in the labor market, which provided stable employment for many Iraqi women in the 1970s and 1980s, as the public sector deteriorated, resulting in lost opportunities and reduced incentives for female workers, forcing them to stay at home and become dependant on their male family members or partners.[153] The sanctions also decimated Iraq’s educational system, once was the best in the Middle East before the sanctions, causing a drop in female enrollment in primary, secondary and higher education levels and an increase in illiteracy among women. The quality of education worsened amid the sanctions due to the destruction of educational institutions and a severe shortage of resources, such as educational materials and teachers.[153] In addition, the psychological impact on women was immense as their domestic responsibilities increased. The combination of economic, educational, and psychological pressures hindered the progress and well-being of Iraqi women during this period.[153]

Women's workplace rights

[edit]In February 2004, OWFI launched a campaign to support fifty female bank employees held on charges of embezzling millions during exchange operations involving banknotes. Embarrassed by the affair, U.S. authorities freed them and their informant was arrested.[154]

OWFI has denounced the Islamist-influenced licensing process for women in professions. Nuha Salim declared:

The insurgents and militias do not want us in the professional sphere for various reasons: some because they believe women were born to stay at home – and cook and clean -- and others because they say that it is contrary to Islam that a man and woman should find themselves in the same place if they are not related.[155]

Women's social life

[edit]In a speech on April 17, 1971, vice-president Saddam Hussein proclaimed that:[156]

Women make up one half of society. Our society will remain backward and in chains unless its women are liberated, enlightened and educated.

Until the 1990s, Iraqi women played an active role in the political and economic development of Iraq.[157] In 1969, the Ba'ath Party established the General Federation of Iraqi Women, which offered many social programs to women, implementing legal reforms advancing women's status under the law and lobbying for changes to the personal status code.[157] In 1986, Iraq became one of the first countries to ratify the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.[157]

During the 1970s and 1980s, Saddam Hussein urged women to fill men's places in schools, universities, hospitals, factories, the army, and the police. However, women's employment subsequently decreased as they were encouraged to make way for returning soldiers in the late 1980s and the 1990s.[158] In general in cases of war, as Nadje Sadig Al-Ali, author of Iraqi Women: Untold Stories from 1948 to the Present, argues, "women carried the conflicting double burden of being the main motors of the state bureaucracy and the public sector, the main breadwinners and heads of households but also the mothers of 'future soldiers.'[159]: 168

In the years following the 1991 Gulf War, many of the positive steps that had been taken to advance women's and girls’ status in Iraqi society were reversed due to a combination of legal, economic, and political factors.[157] As the economy constricted due to sanctions, women were pushed into more traditional roles.[157] Moreover, Saddam Hussein, in an attempt to maintain legitimacy with conservative Islamic fundamentalists, brought in anti-woman legislation, such as the 1990 presidential decree granting immunity to men who had committed honour crimes.[159]: 202 However, despite Saddam's appeals to the anti-women elements of Iraqi society, according to local NGOs, they concluded that "women were treated better during the Saddam Hussein era and their rights were more respected than they are now."[160]

As noted by Yasmin Husein, author of Women in Iraq, the traditional role of women in Iraq is confined mainly to domestic responsibilities and nurturing the family. The wide scale destruction of Iraq's infrastructure (i.e., sanitation, water supply and electricity) as a result of war and sanctions, worsened women's situation. Women, in the process, assumed extra burdens and domestic responsibilities in society, as opposed to their male counterparts.[161]

Hijab and choice of clothing

[edit]In the 1920s, when the Iraqi women's movement begun under the Women's Awakening Club, the opposing conservatives accused it of wanting to unveil women.[162]

Majda al-Haidari, wife of Raouf al-Chadirchi, has sometimes been said to be the first woman in Baghdad to have appeared unveiled in the 1930s,[163] but the Communist Amina al-Rahal, sister of Husain al-Rahal, have also been named as the first unveiled role model in Baghdad.[164] In the 1930s and 1940s, female College students gradually started to appear unveiled,[163] and most upper- and middle class urban women in Iraq were said to be unveiled by 1963.[165] In early Ba'athist Iraq (1968-1979), the Secular Socialist Baath Party women were officially stated to be equal to men, and urban women were normally unveiled.[166][153][167]

In Ba'athist Iraq (1968-2003), the Secular Socialist Baath Party officially stated women to be equal to men, and urban women were normally unveiled.[166][153][167]

After the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, there was a surge in threats and harassment of unveiled women, and the use of hijab became common in Iraq.[168] In 2017, the Iraqi army imposed a burqa ban in the liberated areas of Mosul for the month of Ramadan. Police stated that the temporary ban was for security measures, so that ISIS bombers could not disguise themselves as women.[169]

Women in the 2019 Iraq Protests

[edit]As Zahra Ali said in an interview on transnational feminism in Iraq, the 2019 Iraq protest were primarily organized by young people. Women were included and played a big role in organizing and voicing their protest.[170] Women from all classes, ages, religious affiliations and educational backgrounds participated in the protests, through debating, protesting, organizing or cooking for the protestors. Women-led grassroots movement, such as the Organization of Women’s Freedom in Iraq and the Iraqi Women Network, which emerged after the 2003 invasion, have included demands for justice of social and political issues during the protests and during other actions, amongst pre-existing challenges.[171]

Repression by the government during the protest were in many forms by undermining the uprising with fear tactics which targeted women specifically. Their presence in the demonstrations were considered subversive but one of their many chants were "Do not say it's shameful! A woman's voice is Revolution!"[172]

Women in the government and military

[edit]The Iraqi Constitution states that a quarter of the government must be made up of women.

In the 1950s Iraq became the first Arab country to have a female minister and to have a law that gave women the ability to ask for divorces.[173] Women attained the right to vote and run for public office in 1980. Under Saddam Hussein, women in government got a year's maternity leave.[174]

There is also a large divide among the women themselves, some more modern women wanting a larger percent of women in the Iraqi government still, and some more traditional women believing that they and others are not qualified enough to hold any sort of position in the Iraqi government. Another existing issue is the increasing number of illiterate women in the country. In 1987 approximately 75 percent of Iraqi women were literate. In 2000, Iraq had the lowest regional adult literacy levels, with the percentage of literate women at less than 25 percent. This makes it increasingly difficult to put educated women in a position of power.[175]

Although there are many issues with the current spread of power among genders in Iraq, they are one of the more westernized Arab countries. However, there is hope for women in Iraq. After Hussein's fall in 2003, women's leaders in Iraq saw it as a key opportunity to gain more power in Parliament. The leaders asked for a quota that would have seen that at least 40 percent of the Parliament to be women. In the 2010 National Elections, a group of twelve women started their own party based on women's issues, such as a jobs program for Iraq's 700,000 widows.[176] The United States' involvement in Iraq was seen as detrimental to women. Since Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki was elected as Prime Minister of Iraq, not one woman has been appointed to his senior cabinet.[177] In 2011, Ibtihal al-Zaidi was appointed Minister of State for Women's Affairs, but was strongly criticized after she made remarks declaring that women were not equal to men.[178]

Many women across the country, especially young women, are afraid to voice their political voices for fear of harming their reputations. When they do become active politically, they are seen as being influenced by the United States and trying to push a liberal agenda.[176]

Constitutionally, women lost a number of key rights after the United States entered Iraq. The Family Statutes law, which guarantees women equal rights when it comes to marriage, divorce, inheritance, and custody, was replaced by one that gave power to religious leaders and allowed them to dictate family matters according to their interpretation of their chosen religious text.[177]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Maternal Mortality Ratio (Modeled Estimate, per 100,000 Live Births) - Iraq". data.worldbank.org.

- ^ "Iraq". Women Count Data Hub. UN Women.

- ^ "World Bank Open Data". data.worldbank.org.

- ^ "Index" (PDF). HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORTS. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ "Global Gender Gap Report 2021" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Doreen Insgrams, The Awakened: Women in Iraq. (Third World Centre for Research and Publishing Ltd., Lebanon, 1983)

- ^ a b Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate. Yale University Press. pp. 79–85. ISBN 9780300055832.

- ^ Guillaume, J.P. (2012). "Tawaddud". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ Anthony Nutting, The Arabs. (Hollis and Carter, 1964), p. 196

- ^ Forbes Manz, Beatrice (2003). "Women in Timurid Dynastic Politics". In Guity Nashat; Lois Beck (eds.). Women in Iran from the Rise of Islam to 1800. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252071218.

- ^ "Iraq - British Occupation, Mandatory Regime | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ Efrati, Noga (August 2008). "COMPETING NARRATIVES: HISTORIES OF THE WOMEN'S MOVEMENT IN IRAQ, 1910–58". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 40 (3): 445–466. doi:10.1017/S0020743808081014. ISSN 0020-7438.

- ^ "Layla". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ "The Iraqi Revolution — of 1958 – Association for Diplomatic Studies & Training". adst.org. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ a b Haifa Zangana: City of Widows: An Iraqi Woman's Account of War and Resistance

- ^ Zahra Ali: Women and Gender in Iraq: Between Nation-Building and Fragmentation

- ^ Gustav Adolph Sallas, United States. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Labor Law and Practice in Iraq, 1963, s. 5

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Sonia Corrêa, Rosalind Petchesky, Richard Parker: Sexuality, Health and Human Rights, s. 258

- ^ Jennifer Heath: The Veil: Women Writers on Its History, Lore, and Politics, s. 37.

- ^ Brian Glyn Williams: Counter Jihad: America's Military Experience in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, s. 21

- ^ "Was Life for Iraqi Women Better Under Saddam?". 19 March 2013.

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.25

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.65

- ^ The Crisis of Citizenship in the Arab World. (2017). Nederländerna: Brill. p.435

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.26

- ^ Sherifa Zuhur: Iraq, Women's Empowerment, and Public Policy

- ^ Lancasten, Janine L. "Iraq - Education". www.nationsencyclopedia.com.

- ^ a b c d Efrati, Noga. Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012. Web.

- ^ a b c d e Al-Ali, Nadje. “Reconstructing Gender: Iraqi Women between Dictatorship, War, Sanctions and Occupation.” Third World Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 4/5, 2005, pp. 739–758

- ^ a b Jawad, Al-Assaf. “The Higher Education System in Iraq and Its Future.” International Journal of Contemporary Iraqi Studies 8.1 (2014): 55–72. Web

- ^ a b Press, World. Iraq Women in Culture, Business & Travel: A Profile of Iraqi Women in the Fabric of Society. Petaluma: World Trade Press, 2010. Print.

- ^ a b c d e Enloe, Cynthia. Nimo's War, Emma's War: Making Feminist Sense of the Iraq War. 1st ed. Berkerley: University of California Press, 2010. Web.

- ^ Zuhur, Sherifa. Iraq, Women's Empowerment, and Public Policy. Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2006. Print.

- ^ a b "UNICEF – Iraq – Statistics". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 3 June 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ "Life for Iraq". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ "Iraqi Women: Facts and Figures Ed. Jon Holmes. Inter-Agency Information and Analysis Unit" (PDF). 18 February 2004. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "Founding Statement, National Network to Combat Violence Against Women in Iraq". Women's Leadership Institute. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ a b c "The Organisation of Women's Freedom in Iraq (OWFI)". Front Line Defenders. 15 September 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ جدلية, Jadaliyya. "Women and the Iraqi Revolution". Jadaliyya - جدلية. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ "Organization of Women's Freedom in Iraq (OWFI)". Iraq Business News. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ "Organization of Women's Freedom in Iraq (OWFI) Founding Statement". Worker-communist Party of Iran. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ Nadje Al-Ali, Nadje Sadig Al-Ali, Nicola Christine Pratt, What kind of liberation? Women and the occupation of Iraq, University of California Press, 2009 p. 130.

- ^ "KWRW: Kurdish Women Rights Watch". www.kwrw.org. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ "KWRW: Kurdish Women Rights Watch".

- ^ a b c d "KRG looks to enhance protection of women, children". Al-Monitor. 20 April 2015.

- ^ "KWRW: Kurdish Women Rights Watch".

- ^ a b c "Refugee Health 2007 - Kurdish Refugees From Iraq". www3.baylor.edu. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Backed Turkish Government Bombin... - Che Guevara Lives! - tribe.net". Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Hassanpour, Amir (2001). "The (Re)production of Kurdish Patriarchy in the Kurdish Language". Women of a Non-state Nation (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ "Banaz could have been saved". Kurdish Women's Rights Watch. 20 March 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "Between Nationalism and Women's Rights: The Kurdish Women's Movement in Iraq" (PDF). Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ "New Jersey woman takes on traffickers in Iraq's Kurdistan region - Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East". www.al-monitor.com. 12 February 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ a b Mojab 1996:73, Nationalism and Feminism: The Case of Kurdistan, p 70-71)

- ^ "Pratt writes similarly: "Shahrzad Mojab (2004, 2009), referring to the Iraqi Kurdish context, argues that Islamist-nationalist movements and secular nationalism both stand in the way of transformative gender politics and hinder a feminist analysis of and struggle against gender-based violence and inequalities."" (PDF).

- ^ a b c Lasky, Marjorie P. (22 December 2020). Iraqi Women Under Siege (PDF). Atria (Report). CODEPINK: Women for Peace and Global Exchange. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ Houzan Mahmoud, representative of the Organisation of Women's Freedom in Iraq, voiced similar criticism in 2004, stating that "the Kurdish nationalist parties have violated women's rights and tried to suppress progressive women's organisations. In July 2000, they attacked a women's shelter and the offices of an independent women's organisation. Both were saving the lives of Kurdish women fleeing "honour" killings and domestic violence. More than 8,000 women have died in "honour" killings since the (Kurdish) nationalists have been in control." The Guardian

- ^ Pratt writes similarly: "There is a link between the Kurdish national struggle and the neglect of women's rights". What Kind of Liberation?: Women and the Occupation of Iraq, Nadje Al-Ali, Nicola Pratt, p.108ff ISBN 978-0-520-26581-3

- ^ Dr. Yasmine Jawad. "The Plight of Iraqi Women, 10 years of suffering" (PDF). www.s3.amazonaws.com.

- ^ Shahrzad, Mojab (2003). "Kurdish Women in the Zone of Genocide and Gendercide" (PDF). Al-Raida. 21 (103): 20–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ Zuhur, S. (2006). Iraq, Women's Empowerment, and Public Policy. USA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College. p. 12-13

- ^ Zuhur, S. (2006). Iraq, Women's Empowerment, and Public Policy. USA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College. p. 12-13

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.20

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.21

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.21

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.22

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.21

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.22-25

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Efrati, N. (2012). Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present. Tyskland: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.23

- ^ Zuhur, S. (2006). Iraq, Women's Empowerment, and Public Policy. USA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College. p. 12-13

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.25

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.23

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.65

- ^ The Crisis of Citizenship in the Arab World. (2017). Nederländerna: Brill. p.435

- ^ Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Women and Democracy in Iraq: Gender, Politics and Nation-Building. Indien: Bloomsbury Publishing. p.26

- ^ Al-Jawaheri, Yasmin H. Women in Iraq. New York: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2008. 37-51. Print.

- ^ "Gender equality". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Sarhan, Afif; Davies, Caroline (11 May 2008). "My Daughter Deserved to Die for Falling in Love". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ "Iraq". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ Isobel Coleman, Women, Islam, and the New Iraq, Foreign affairs, January / February 2006.

- ^ OWFI, Statement of the Organization of Women's Freedom in Iraq on the Governing Council's adoption of Islamic Shari’a, January 14, 2004

- ^ a b Nicolas Dessaux, La lutte des femmes en Irak avant et depuis l’occupation, Courant Alternatif, n° 148, avril 2005.

- ^ "Chaos de la societe civile". Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Laurent Scapin, Interview d’Houzan Mahmoud : Irak, Résistance ouvrière et féministe (2/2), Alternative libertaire, novembre 2004.

- ^ Yanar Mohammed, Irak : une constitution inhumaine pour les femmes.

- ^ Nadje Al-Ali, Nadje Sadig Al-Ali, Nicola Christine Pratt, What kind of liberation? Women and the occupation of Iraq, University of California Press, 2009 p. 105.

- ^ Jervis, Rick (4 May 2005). "'Pleasure marriages' regain popularity in Iraq". USA Today. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ "Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change - UNICEF DATA" (PDF). 22 July 2013.

- ^ "Human Rights Watch lauds FGM law in Iraqi Kurdistan". Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b Iraqi Kurdistan: Law Banning FGM Not Being Enforced Human Rights Watch, August 29, 2012

- ^ UNICEF 2013, pp. 27 (for eight percent), 31 (for the regions).

- ^ a b c d Yasin, Berivan A.; Al-Tawil, Namir G.; Shabila, Nazar P.; Al-Hadithi, Tariq S. (8 September 2013). "Female genital mutilation among Iraqi Kurdish women: A cross-sectional study from Erbil city". BMC Public Health. 13: 809. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-809. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 3844478. PMID 24010850.

- ^ "Female Genital Mutilation (FGM): A Survey on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice among Households in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ "Female genital mutilation among Iraqi Kurdish women: a cross-sectional study from Erbil city". 7thspace.com.

- ^ "Female Genital Mutilation: It's a crime not culture". Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Paley, Amit R. (29 December 2008). "For Kurdish Girls, a Painful Ancient Ritual: The Widespread Practice of Female Circumcision in Iraq's North Highlights The Plight of Women in a Region Often Seen as More Socially Progressive". Washington Post Foreign Service. p. A09. Actual quotes: "Kurdistan is the only known part of Iraq --and one of the few places in the world--where female genital mutilation is widespread. More than 60 percent of women in Kurdish areas of northern Iraq have been mutilated, according to a study conducted this year. In at least one Kurdish territory, 95 percent of women have undergone the practice, which human rights groups call female genital mutilation.

- ^ "Kurdish FGM campaign seen as global model". Rudaw. 16 June 2015.

- ^ a b "» Iraq". Stopfgmmideast.org. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Female Genital Mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan – A Study", WADI, accessed 15 February 2010.

- ^ a b Burki, T. (2010), Reports focus on female genital mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan. The Lancet, 375(9717), 794

- ^ a b "Draft for a Law Prohibiting Female Genital Mutilation is submitted to the Kurdish Regional Parliament", Stop FGM in Kurdistan, accessed 21 November 2010.

- ^ a b Memorandum to prevent female genital mutilation in Iraq PUK, Kurdistan (May 2, 2013)

- ^ "Iraqi Kurdistan: Law Banning FGM Not Being Enforced | Human Rights Watch". Hrw.org. 29 August 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "At a Crossroads". Human Rights Watch. 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Kurdistan: Over 6,000 Women Killed in 2014". BasNews. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- ^ Kurdish Human Rights Project European Parliament Project: The Increase in Kurdish Women Committing Suicide Final Report Vian Ahmed Khidir Pasha, Member of Kurdistan National Assembly, Member of Women's Committee, Erbil, Iraq, 25 January 2007

- ^ Kurdish Human Rights Project European Parliament Project: The Increase in Kurdish Women Committing Suicide Final Report Reported by several NGOs and members of Kurdistan National Assembly over course of study to Project Team Member Tanyel B. Taysi.

- ^ a b Kurdish Human Rights Project European Parliament Project: The Increase in Kurdish Women Committing Suicide Final Report

- ^ "Human Rights Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ "Human Rights Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ "A Killing Set Honor Above Love". The New York Times. 21 November 2010.

- ^ a b "The Penal-Code with Amendments" (PDF). 21 October 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ Iraq: Analysts say violence will continue to increase, IRIN, 21 September 2006.

- ^ a b c Madre's Sister Organization in Iraq. The Organization of Women's Freedom in Iraq, Madre, 2007.

- ^ Shelter gives strength to women Archived 2008-10-15 at the Wayback Machine, IRIN, 12 December 2003.

- ^ Nadia Mahmoud, Supporting a Women's Shelter in Baghdad is a humanitarian task!, 25 août 2003.

- ^ Anna Badkhen, Baghdad Underground, Summer 2009.

- ^ Enloe, Cynthia (2004). The curious feminist. Searching for Women in a new Age of Empire. University of California Press. pp. 301–302.

- ^ Vidéo : Fighting for women's rights in Iraq, interview de Yanar Mohammed au sujet du meurtre de Dua Khalil Aswad, 26 juin 2007, sur le site CNN.

- ^ a b OWFI, Prostitution and Trafficking of Women and Girls in Iraq, March 2010.

- ^ "Iraq's unspeakable crime: Mothers pimping daughters". Time Magazine. 7 March 2009. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ What Kind of Liberation?: Women and the Occupation of Iraq, Nadje Al-Ali, Nicola Pratt, p. 108ff

- ^ "Iraq – 2013 Trafficking in Persons Report". U.S. Department of State.

- ^ a b "Iraq – 2015 Trafficking in Persons Report". U.S. Department of State.

- ^ "EXCLUSIVE: Report exposes rampant sexual violence in refugee camps".

- ^ "Iraq urged to investigate attacks on women human rights defenders". UN News. 2 October 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ a b Al-Ali, Nadje, and Nicola Pratt. What Kind of Liberation: Women and the Occupation of Iraq. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2009. Print.

- ^ Ghali Hassan, 'How to Erase Women's Rights in Iraq' (Global Research, October, 2005)[better source needed]

- ^ a b Guernica, 'First Victims of Freedom (Magazine of Arts and Politics, May, 2007)

- ^ Mark Lattimer (13 December 2007). "Freedom Lost". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016.

- ^ a b Goessmann, Katharina; Ibrahim, Hawkar; Neuner, Frank (18 September 2020). "Association of War-Related and Gender-Based Violence With Mental Health States of Yazidi Women". JAMA Network Open. 3 (9): e2013418. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13418. ISSN 2574-3805. PMC 7501539. PMID 32945873.

- ^ Organisation pour la liberté des femmes, Rapport été 2006

- ^ Organization of Women's Freedom in Iraq, The Organisation for Women's Freedom in Iraq (OWFI) has launched an on-line petition calling on the Iraqi Government to end capital punishment., 25 juillet 2009.

- ^ "Abu Ghraib culture lives on in Iraq prisons". Iraq Sun. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Al-Jawaheri, Yasmin Husein (30 January 2008). Women in Iraq: The Gender Impact of International Sanctions. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85771-834-1. Cite error: The named reference "books.google.com" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Eyewitness view of women in Iraq". News and Letters. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ Irakiennes forcées au chômage et au divorce, IRIN, June 1, 2007.

- ^ Women - One half of our society. Wikisource

- ^ a b c d e Background on Women's Status in Iraq Prior to the Fall of the Saddam Hussein Government. Human Rights Watch

- ^ Women's Rights in the Middle East and North Africa 2010 - Iraq. Refworld

- ^ a b Nadje Sadig Al-Ali. Iraqi Women: Untold stories from the 1948 to the Present (Zed Books, London, 2007)

- ^ Women were more respected under Saddam, say women's groups. The New Humanitarian

- ^ Yasmine Hussein, Al Jawaheri (2008), Women in Iraq, London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 118-119

- ^ Noga Efrati: Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present

- ^ a b Haifa Zangana: City of Widows: An Iraqi Woman's Account of War and Resistance

- ^ Zahra Ali: Women and Gender in Iraq: Between Nation-Building and Fragmentation

- ^ Gustav Adolph Sallas, United States. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Labor Law and Practice in Iraq, 1963, s. 5

- ^ a b Sonia Corrêa, Rosalind Petchesky, Richard Parker: Sexuality, Health and Human Rights, s. 258

- ^ a b Brian Glyn Williams: Counter Jihad: America's Military Experience in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, s. 21

- ^ Sherifa Zuhur: Iraq, Women's Empowerment, and Public Policy

- ^ "Iraqi army imposes Ramadan 'burqa ban' in Mosul fearing Isis will use it for attacks". The Independent. 1 June 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ "x.com". X (formerly Twitter). Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ "Women, Gender, and the Iraqi Uprising: Inequality, Space, and Feminist Prospects (In Arabic)". Economic Research Forum (ERF). Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ Bivins, Alyssa (4 April 2023). "Iraqi Women's Activism—20 Years After the US Invasion". MERIP. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ Coughlin, Kathryn M. "Muslim Women and the Family in Iraq: Modern World". ABC-CLIO. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ IRAQ: Women Miss Saddam. Inter Press Service

- ^ "Background on Women's Status in Iraq Prior to the Fall of the Saddam Hussein Government". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ a b Leland, John (17 February 2010). "Iraqi Women Are Seeking Greater Political Influence". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ a b Salbi, Zainab (18 March 2013). "Why Women Are Less Free 10 Years after the Invasion of Iraq". CNN. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ AFP (5 March 2012). "Decades before Iraq has woman PM: minister". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 27 March 2025.

Bibliography

[edit]- Nicolas Dessaux, Résistances irakiennes : contre l'occupation, l'islamisme et le capitalisme, Paris, L'Échappée, coll. Dans la mêlée, 2006. Critiques par le Monde Diplomatique, Dissidences, Ni patrie, ni frontières. Publié en Turc sous le titre Irak'ta Sol Muhalefet İşgale, İslamcılığa ve Kapitalizme Karşı Direnişle, Versus Kitap / Praxis Kitaplığı Dizisi, 2007. ISBN 978-2-915830-10-1 [Interviews de personnalités de la résistance civile irakienne, don't Surma Hamid, Houzan Mahmoud et Nadia Mahmood, avec notes et introduction permettant de les contextualiser]

- Yifat Susskind, Promising Democracy, Imposing Theocracy: Gender-Based Violence and the US War on Iraq, Madre, 2007 (lire en ligne, lire en format .pdf) [Bilan de la situation des femmes en Irak depuis 2003]

- Houzan Mahmoud, Genre et développement. Les acteurs et actrices des droits des femmes et de la solidarité internationale se rencontrent et échangent sur leurs pratiques. Actes du colloque 30 et 31 mars, Lille , Paris, L'Harmattan, 2008, p. 67-76.

- Osamu Kimura, Iraqi Civil Resistance, Video series « Creating the 21th [sic?] Century » n° 8, VHS/DVD, Mabui-Cine Coop Co. Ltd, 2005 [DVD produced in Japan profiling several civil rights activist organizations in Iraq, one of which is OWFI.]

- Osamu Kimura, Go forward, Iraq Freedom Congress. Iraq Civil Resistance Part II, Video series « Creating the 21th [sic?] Century » n° 9, VHS/DVD, Mabui-Cine Coop Co. Ltd, 2005 [durée : 32 mn] (DVD documentary produced in Japan focussed on civil resistance in Iraq, notably includes an interview with Yanar Mohammed.)

- Al-Ali, Nadje, and Nicola Pratt. What Kind of Liberation: Women and the Occupation of Iraq. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2009. Print.

- Al-Jawaheri, Yasmin H. Women in Iraq. New York: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2008. 37-51. Print.

- Fernea, Elizabeth W. Guests of the Sheik. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1969. 12-13. Print.

- Harris, George L. Iraq: Its People, Its Society, Its Culture. New Haven, CT: Hraf Press, 1958. 11-17. Print.Iraq . Baltimore: The Lord Baltimore Press, 1946. 26-34. Print.

- Khan, Noor, and Heidi Vogt. Taliban Throws Acid on Schoolgirls Sweetness & Light, Nov. 2001. Web. 20 Jan. 2010.

- Raphaeli, Nimrod. Culture in Iraq Middle East Forum, July 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2010.

- Stone, Peter G., and Joanne F. Bajjaly, eds. The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq. Rochester, NY: The Boydell Press, 2008. 24-40. Print.

External links

[edit]- Official website of OWFI (archived)

- Solidarité Irak[usurped]