Neoclassicism (music)

Neoclassicism in music was a twentieth-century trend, particularly current in the interwar period, in which composers sought to return to aesthetic precepts associated with the broadly defined concept of "classicism", namely order, balance, clarity, economy, and emotional restraint. As such, neoclassicism was a reaction against the unrestrained emotionalism and perceived formlessness of late Romanticism, as well as a "call to order" after the experimental ferment of the first two decades of the twentieth century. The neoclassical impulse found its expression in such features as the use of pared-down performing forces, an emphasis on rhythm and on contrapuntal texture, an updated or expanded tonal harmony, and a concentration on absolute music as opposed to Romantic program music.

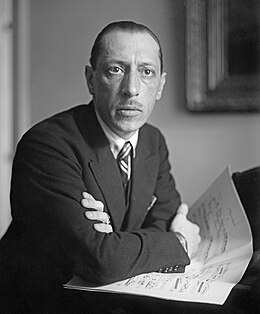

In form and thematic technique, neoclassical music often drew inspiration from music of the eighteenth century, though the inspiring canon belonged as frequently to the Baroque (and even earlier periods) as to the Classical period—for this reason, music which draws inspiration specifically from the Baroque is sometimes termed neo-Baroque music. Neoclassicism had two distinct national lines of development, French (proceeding partly from the influence of Erik Satie and represented by Igor Stravinsky, who was in fact Russian-born) and German (proceeding from the "New Objectivity" of Ferruccio Busoni, who was actually Italian, and represented by Paul Hindemith). Neoclassicism was an aesthetic trend rather than an organized movement; even many composers not usually thought of as "neoclassicists" absorbed elements of the style.

People and works

[edit]Although the term "neoclassicism" refers to a twentieth-century movement, there were important nineteenth-century precursors. In pieces such as Franz Liszt's À la Chapelle Sixtine (1862), Edvard Grieg's Holberg Suite (1884), Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's divertissement from The Queen of Spades (1890), George Enescu's Piano Suite in the Old Style (1897) and Max Reger's Concerto in the Old Style (1912), composers "dressed up their music in old clothes in order to create a smiling or pensive evocation of the past".[1]

Sergei Prokofiev's Symphony No. 1 (1917) is sometimes cited as a precursor of neoclassicism.[2] Prokofiev himself thought that his composition was a "passing phase" whereas Stravinsky's neoclassicism was by the 1920s "becoming the basic line of his music".[3] Richard Strauss also introduced neoclassical elements into his music, most notably in his orchestral suite Le bourgeois gentilhomme Op. 60, written in an early version in 1911 and its final version in 1917.[4]

Ottorino Respighi was also one of the precursors of neoclassicism with his Ancient Airs and Dances Suite No. 1, composed in 1917. Instead of looking at musical forms of the eighteenth century, Respighi, who, in addition to being a renowned composer and conductor, was also a notable musicologist, reached back to Italian music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. His fellow contemporary composer Gian Francesco Malipiero, also a musicologist, compiled a complete edition of the works of Claudio Monteverdi. Malipiero's relation with ancient Italian music was not simply aiming at a revival of antique forms within the framework of a "return to order", but an attempt to revive an approach to composition that would allow the composer to free himself from the constraints of the sonata form and of the over-exploited mechanisms of thematic development.[5]

Igor Stravinsky's first foray into the style began in 1919/20 when he composed the ballet Pulcinella, using themes which he believed to be by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (it later came out that many of them were not, though they were by contemporaries). American Composer Edward T. Cone describes the ballet "[Stravinsky] confronts the evoked historical manner at every point with his own version of contemporary language; the result is a complete reinterpretation and transformation of the earlier style".[6] Later examples are the Octet for winds, the "Dumbarton Oaks" Concerto, the Concerto in D, the Symphony of Psalms, Symphony in C, and Symphony in Three Movements, as well as the opera-oratorio Oedipus Rex and the ballets Apollo and Orpheus, in which the neoclassicism took on an explicitly "classical Grecian" aura. Stravinsky's neoclassicism culminated in his opera The Rake's Progress, with a libretto by W. H. Auden.[7] Stravinskian neoclassicism was a decisive influence on the French composers Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc, Arthur Honegger and Germaine Tailleferre, as well as on Bohuslav Martinů, who revived the Baroque concerto grosso form in his works.[8] Pulcinella, as a subcategory of rearrangement of existing Baroque compositions, spawned a number of similar works, including Alfredo Casella's Scarlattiana (1927), Poulenc's Suite Française, Ottorino Respighi's Ancient Airs and Dances and Gli uccelli,[9] and Richard Strauss's Dance Suite from Keyboard Pieces by François Couperin and the related Divertimento after Keyboard Pieces by Couperin, Op. 86 (1923 and 1943, respectively).[10] Starting around 1926 Béla Bartók's music shows a marked increase in neoclassical traits, and a year or two later acknowledged Stravinsky's "revolutionary" accomplishment in creating novel music by reviving old musical elements while at the same time naming his colleague Zoltán Kodály as another Hungarian adherent of neoclassicism.[11]

A German strain of neoclassicism was developed by Paul Hindemith, who produced chamber music, orchestral works, and operas in a heavily contrapuntal, chromatically inflected style, best exemplified by Mathis der Maler. Roman Vlad contrasts the "classicism" of Stravinsky, which consists in the external forms and patterns of his works, with the "classicality" of Busoni, which represents an internal disposition and attitude of the artist towards works.[12] Busoni wrote in a letter to Paul Bekker, "By 'Young Classicalism' I mean the mastery, the sifting and the turning to account of all the gains of previous experiments and their inclusion in strong and beautiful forms".[13]

Neoclassicism found a welcome audience in Europe and America, as the school of Nadia Boulanger promulgated ideas about music based on her understanding of Stravinsky's music. Boulanger taught and influenced over 600 musicians,[14] including many notable composers, including Grażyna Bacewicz, Lennox Berkeley, Elliott Carter, Francis Chagrin, Aaron Copland, David Diamond, Irving Fine, Harold Shapero, Jean Françaix, Roy Harris, Igor Markevitch, Darius Milhaud, Astor Piazzolla, Walter Piston, Ned Rorem, and Virgil Thomson.

In Spain, Manuel de Falla's neoclassical Concerto for Harpsichord, Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Violin, and Cello of 1926 was perceived as an expression of "universalism" (universalismo), broadly linked to an international, modernist aesthetic.[15] In the first movement of the concerto, Falla quotes fragments of the fifteenth-century villancico "De los álamos, vengo madre". He had similarly incorporated quotations from seventeenth-century music when he first embraced neoclassicism in the puppet-theatre piece El retablo de maese Pedro (1919–23), an adaptation from Cervantes's Don Quixote. Later neoclassical compositions by Falla include the 1924 chamber cantata Psyché and incidental music for Pedro Calderón de la Barca's, El gran teatro del mundo, written in 1927.[16] In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Roberto Gerhard composed in the neoclassical style, including his Concertino for Strings, the Wind Quintet, the cantata L'alta naixença del rei en Jaume, and the ballet Ariel.[17] Other important Spanish neoclassical composers are found amongst the members of the Generación de la República (also known as the Generación del 27), including Julián Bautista, Fernando Remacha, Salvador Bacarisse, and Jesús Bal y Gay.[18][19][20][21]

A neoclassical aesthetic was promoted in Italy by Alfredo Casella, who had been educated in Paris and continued to live there until 1915, when he returned to Italy to teach and organize concerts, introducing modernist composers such as Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg to the provincially minded Italian public. His neoclassical compositions were perhaps less important than his organizing activities, but especially representative examples include Scarlattiana of 1926, using motifs from Domenico Scarlatti's keyboard sonatas, and the Concerto romano of the same year.[22] Casella's colleague Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco wrote neoclassically inflected works which hark back to early Italian music and classical models: the themes of his Concerto italiano in G minor of 1924 for violin and orchestra echo Vivaldi as well as sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italian folksongs, while his highly successful Guitar Concerto No. 1 in D of 1939 consciously follows Mozart's concerto style.[23]

Portuguese representatives of neoclassicism include two members of the "Grupo de Quatro", Armando José Fernandes and Jorge Croner de Vasconcellos, both of whom studied with Nadia Boulanger.[24]

In South America, neoclassicism was of particular importance in Argentina, where it differed from its European model in that it did not seek to redress recent stylistic upheavals which had simply not occurred in Latin America. Argentine composers associated with neoclassicism include Jacobo Ficher, José María Castro, Luis Gianneo, and Juan José Castro.[25] The most important twentieth-century Argentine composer, Alberto Ginastera, turned from nationalistic to neoclassical forms in the 1950s (e.g., Piano Sonata No. 1 and the Variaciones concertantes) before moving on to a style dominated by atonal and serial techniques. Roberto Caamaño, professor of Gregorian chant at the Institute of Sacred Music in Buenos Aires, employed a dissonant neoclassical style in some works and a serialist style in others.[26]

Although the well-known Bachianas Brasileiras of Heitor Villa-Lobos (composed between 1930 and 1947) are cast in the form of Baroque suites, usually beginning with a prelude and ending with a fugal or toccata-like movement and employing neoclassical devices such as ostinato figures and long pedal notes, they were not intended so much as stylized recollections of the style of Bach as a free adaptation of Baroque harmonic and contrapuntal procedures to music in a Brazilian style.[27][28] Brazilian composers of the generation after Villa-Lobos more particularly associated with neoclassicism include Radamés Gnattali (in his later works), Edino Krieger, and the prolific Camargo Guarnieri, who had contact with but did not study under Nadia Boulanger when he visited Paris in the 1920s. Neoclassical traits figure in Guarnieri's music starting with the second movement of the Piano Sonatina of 1928, and are particularly notable in his five piano concertos.[27][29][30]

The Chilean composer Domingo Santa Cruz Wilson was so strongly influenced by the German variety of neoclassicism that he became known as the "Chilean Hindemith".[31]

In Cuba, José Ardévol initiated a neoclassical school, though he himself moved on to a modernistic national style later in his career.[32][33][31]

Even the atonal school, represented for example by Arnold Schoenberg, showed the influence of neoclassical ideas. After his early style of 'Late Romanticism' (exemplified by his string sextet Verklärte Nacht) had been supplanted by his Atonal period, and immediately before he embraced twelve-tone serialism, the forms of Schoenberg's works after 1920, beginning with opp. 23, 24, and 25 (all composed at the same time), have been described as "openly neoclassical", and represent an effort to integrate the advances of 1908 to 1913 with the inheritance of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[34] Schoenberg attempted in those works to offer listeners structural points of reference with which they could identify, beginning with the Serenade, op. 24, and the Suite for piano, op. 25.[35] Schoenberg's pupil Alban Berg actually came to neoclassicism before his teacher, in his Three Pieces for Orchestra, op. 6 (1913–14), and the opera Wozzeck,[36] which uses closed forms such as suite, passacaglia, and rondo as organizing principles within each scene. Anton Webern also achieved a sort of neoclassical style through an intense concentration on the motif.[37] However, his 1935 orchestration of the six-part ricercar from Bach's Musical Offering is not regarded as neoclassical because of its concentration on the fragmentation of instrumental colours.[9]

Other neoclassical composers

[edit]Some composers below may have only written music in a neoclassical style during a portion of their careers.

- Arthur Berger (1912–2003)

- Carlos Chávez (1899–1978)[38]

- Salvador Contreras (1910–1982)

- Einar Englund (1916–1999)

- Pierre Gabaye (1930–2019)

- Harald Genzmer (1909–2007)

- Giorgio Federico Ghedini (1892–1965)

- Vagn Holmboe (1909–1996)

- Stefan Kisielewski (1911–1991)

- Iša Krejčí (1904–1968)

- Ernst Krenek (1900–1991)

- Franco Margola (1908–1992)

- Marcel Mihalovici (1898–1985)

- Giorgio Pacchioni (born 1947)

- Goffredo Petrassi (1904–2003)

- Gabriel Pierné (1863–1937)[39][40][41]

- Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

- Knudåge Riisager (1897–1974)

- Albert Roussel (1869–1937)

- Alexandre Tansman (1897–1986)

- Michael Tippett (1905–1998)

- Dag Wirén (1905–1986)

See also

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Bónis, Ferenc (1983). "Zoltán Kodály, a Hungarian Master of Neoclassicism". Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 25 (1–4): 73–91.

- Cone, Edward T. (July 1962). "The Uses of Convention: Stravinsky and His Models". The Musical Quarterly. XLVIII (3): 287–299. doi:10.1093/mq/XLVIII.3.287.

- Cowell, Henry (March–April 1933). "Towards Neo-Primitivism". Modern Music. 10 (3): 149–53. Reprinted in Essential Cowell: Selected Writings on Music by Henry Cowell 1921–1964, edited by Richard Carter Higgins and Bruce McPherson, preface by Kyle Gann, pp. 299–303. Kingston, New York City: Documentext, 2002. ISBN 978-0-929701-63-9.

- Hess, Carol A. (Spring 2013). "Copland in Argentina: Pan Americanist Politics, Folklore, and the Crisis in Modern Music". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 66 (1): 191–250. doi:10.1525/jams.2013.66.1.191.

- Malipiero, Gian Francesco. 1952. [Essay?]. In L'opera di Gian Francesco Malipiero: Saggi di scrittori italiani e stranieri con una introduzione di Guido M. Gatti, seguiti dal catalogo delle opere con annotazioni dell'autore e da ricordi e pensieri dello stesso, edited by Guido Maggiorino Gatti, [page needed] Treviso: Edizioni di Treviso.

- Moody, Ivan (1996). "'Mensagens': Portuguese Music in the 20th Century". Tempo, new series, no. 198 (October): 2–10.

- Rosen, Charles (1975). Arnold Schoenberg. Modern Masters. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-13316-7 (cloth) ISBN 0-670-01986-0 (pbk). UK edition, titled simply Schoenberg. London: Boyars; Glasgow: W. Collins ISBN 0-7145-2566-9 Paperback reprint, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-691-02706-4.

- Ross, Alex (2010). "Strauss's Place in the Twentieth Century". In Charles Youmans (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Richard Strauss. Cambridge Companions to Music Series. Cambridge and New York City: Cambridge University Press. pp. 195–212. ISBN 9780521728157.

- Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 9780195170672.

- Sorce Keller, Marcello (1978). "A Bent for Aphorisms: Some Remarks about Music and about His Own Music by Gian Francesco Malipiero". The Music Review. 39 (3–4): 231–239.

Footnotes

- ^ Albright, Daniel (2004). Modernism and Music: An Anthology of Sources. University of Chicago Press. p. 276. ISBN 0-226-01267-0.

- ^ Whittall, Arnold (1980). "Neo-classicism". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- ^ Prokofiev, Sergey (1991). "Short Autobiography", translated by Rose Prokofieva, revised and corrected by David Mather. In Soviet Diary 1927 and Other Writings. London: Faber and Faber. p. 273. ISBN 0-571-16158-8.

- ^ Ross 2010, p. 207.

- ^ Malipiero 1952, p. 340, cited from Sorce Keller 1978.[page needed][failed verification]

- ^ Cone 1962, p. 291.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Stravinsky, Igor" (§8) by Stephen Walsh.

- ^ Large, Brian (1976). Martinu. Teaneck NJ: Holmes & Meier. p. 100. ISBN 978-0841902565.

- ^ a b Simms, Bryan R. 1986. "Twentieth-Century Composers Return to the Small Ensemble". In The Orchestra: A Collection of 23 Essays on Its Origins and Transformations, edited by Joan Peyser, 453–74. New York City: Charles Scribner's Sons p. 462. Reprinted in paperback, Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4234-1026-3.

- ^ Heisler, Wayne (2009). The Ballet Collaborations of Richard Strauss. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-58046-321-8.

- ^ Bónis 1983, pp. 73–4.

- ^ Samson, Jim (1977). Music in Transition: A Study of Tonal Expansion and Atonality, 1900–1920. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 28. ISBN 0-393-02193-9.

- ^ Busoni, Ferruccio (1957). The Essence of Music, and Other Papers. Translated by Rosamond Ley. London: Rockliff. p. 20.

- ^ Tobin, R. James (2014). Neoclassical Music in America: Voices of Clarity and Restraint. Modern Traditionalist Classical Music. Blue Ridge Summit: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-8108-8440-3.

- ^ Hess, Carol A. (2001). Manuel de Falla and Modernism in Spain, 1898–1936. University of Chicago Press. pp. 3–8. ISBN 9780226330389.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Falla (y Matheu), Manuel de" by Carol A. Hess.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Gerhard, Roberto [Gerhard Ottenwaelder, Robert]" by Malcom MacDonald.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Spain" (§I: Art Music 6: 20th Century) by Belén Pérez Castillo.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Bacarisse (Chinoria), Salvador" by Christiane Heine.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Remacha (Villar), Fernando" by Christiane Heine.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Bautista, Julián" by Susana Salgado.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Casella, Alfredo" by John C. G. Waterhouse and Virgilio Bernardoni.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Mario" by James Westby.

- ^ Moody 1996, p. 4.

- ^ Hess 2013, pp. 205–6.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Argentina" (i) by Gerard Béhague and Irma Ruiz.

- ^ a b New Grove Dict. 2001, "Brazil" by Gerard Béhague.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Villa-Lobos, Heitor" by Gerard Béhague.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Guarnieri, (Mozart) Camargo" by Gerard Béhague.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Krieger, Edino" by Gerard Béhague.

- ^ a b Hess 2013, p. 205.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Cuba, Republic of" by Gerard Béhague and Robin Moore.

- ^ New Grove Dict. 2001, "Ardévol (Gimbernat), José" by Victoria Eli Rodríguez.

- ^ Cowell 1933, p. 150; Rosen 1975, pp. 70–3.

- ^ Keillor, John (2009). "Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31". Allmusic.com website. (Accessed 4 April 2010).

- ^ Rosen 1975, p. 87.

- ^ Rosen 1975, p. 102.

- ^ Oja, Carol J. 2000. Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 275–9. ISBN 978-0-19-516257-8.

- ^ Hurwitz, David (n.d.). "Pierne Timpani TEN C". ClassicsToday.com (accessed 1 July 2015).

- ^ Lewis, Uncle Dave (n.d.). “Christian Ivaldi / Solistes de l'orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg: Gabriel Pierné: La Musique de Chambre, Vol. 2” AllMusic Review (accessed 1 July 2015).

- ^ Sharpe, Roderick L. (2009). "Gabriel Pierné (b. Metz, Loraine, 16 August 1863 – d. Ploujean, Finistère, 17 July 1937): Voyage au Pays du Tendre (d'après la Carte du Tendre)". Konrad von Abel & Phenomenology of Music: Repertoire & Opera Explorer: Vorworte—Prefaces. Munich: Musikproduktion Jürgen Höflich.

Further reading

[edit]- Lanza, Andrea (2008). "An Outline of Italian Instrumental Music in the 20th Century". Sonus: A Journal of Investigations into Global Musical Possibilities 29, no. 1:1–21. ISSN 0739-229X

- Messing, Scott (1988). Neoclassicism in Music: From the Genesis of the Concept Through the Schoenberg/Stravinsky Polemic. Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-878822-73-4.

- Salgado, Susana (2001b). "Caamaño, Roberto". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Stravinsky, Igor (1970). Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons (from the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures delivered in 1939–1940). Harvard College, 1942. English translation by Arthur Knodell and Ingolf Dahl, preface by George Seferis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-67855-9.

- New Grove Dict. 2001, "Neo-classicism" by Arnold Whittall.