Neurogenic bowel dysfunction

| Neurogenic bowel dysfunction | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Neurogenic bowel |

| |

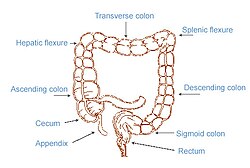

| The image shows the 4 parts of the colon (ascending, transverse, descending and sigmoid) and the rectum. Feces are transported along and stored in the rectum before excretion. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

Neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) is reduced ability or inability to control defecation due to deterioration of or injury to the nervous system, resulting in fecal incontinence or constipation.[1] It is common in people with spinal cord injury (SCI), multiple sclerosis (MS) or spina bifida.[2]

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract) has a complex control mechanism that relies on coordinated interaction between muscular contractions and neuronal impulses (nerve signals).[3] Fecal incontinence or constipation occurs when there is a problem with normal bowel functioning. This could be for a variety of reasons. The normal defecation pathway involves contractions of the colon which helps mix the contents, absorb water and propel the contents along. This results in feces moving along the colon to the rectum.[4] The presence of stool in the rectum causes reflexive relaxation of the internal anal sphincter (rectoanal inhibitory reflex), so the contents of the rectum can move into the anal canal. This causes the conscious feeling of the need to defecate. At a suitable time the brain can send signals causing the external anal sphincter and puborectalis muscle to relax as these are under voluntary control and this allows defecation to take place.[4][5]

Spinal cord injury and other neurological problems mostly affect the lower GI tract (i.e., jejunum, ileum, and colon) leading to symptoms of incontinence or constipation. However, the upper GI tract (i.e., esophagus, stomach, and duodenum) may also be affected and patients with NBD often present with multiple symptoms.[6][7] Research shows there is a high prevalence of upper abdominal complaints, for example a study showed that approximately 22% of SCI patients reported feeling bloated,[6][8] and about 31% experienced abdominal distension.[6][9]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]In NBD there may be fecal incontinence, constipation, or both combined.[10] One type of constipation which may occur in people with NBD is obstructed defecation.[10]

NBD can have an impact on a person's life as it often leads to difficulties with self-esteem, personal relationships, employment, social life and can also reduce a person's independence.[11][12] There is also evidence from studies showing that faecal incontinence can increase the risk of depression and anxiety.[13]

Causes

[edit]Different neurological disorders affect the GI tract in different ways:

Spinal cord injury

[edit]Bowel dysfunction caused by a spinal cord injury will vary greatly depending on the severity and level of the spinal cord lesion. In complete spinal cord injury both sensory and motor functions are completely lost below the level of the lesion so there is a loss of voluntary control and loss of sensation of the need to defecate.[14] An incomplete spinal cord injury is one where there may still be partial sensation or motor function below the level of the lesion.[14]

Colorectal dysfunction due to spinal cord injury can be classified in to two types: an upper motor neuron lesion or lower motor neuron lesion. Problems with the upper motor neuron in a neurogenic bowel results in a hypertonic and spastic bowel because the defecation reflex centre, which causes the involuntary contraction of muscles of the rectum and anus, remains intact.[5] However, the nerve damage results in disruption to the nerve signals and therefore there is an inability to relax the anal sphincters and defecate, often leading to constipation.[5] An upper motor neuron lesion is one that is above the conus medullaris of the spinal cord and therefore above vertebral level T12.[15] On the other hand, a lower motor neuron lesion can cause areflexia and a flaccid external anal sphincter so most commonly leading to incontinence. Lower motor neuron lesions are damage to nerves that are at the level of or below the conus medullaris and below vertebral level T12. However, both upper and lower motor neuron disorders can lead to constipation and/ or incontinence.[16][15]

Spinal cord injury above the S2, S3, S4 level results in preserved reflexes in the rectum and anal canal. Hence the sphincter will remain contracted.[14] Spinal cord injury below this level results in absent reflexes. In this situation, the rectum will be flaccid and the sphincter will be relaxed.[14]

Spina bifida

[edit]Individuals with spina bifida myelomeningocele have a neural tube that has failed to completely form.[17][18] This is most commonly in the lower back area in the region of the conus medullaris or cauda equina. Nervous system lesions above the conus medullaris result in upper motor neurogenic bowel dysfunction leading to failure to evacuate the bowel, resulting in constipation or impaction. Lesions at or below the level of the conus medullaris result in lower motor neurogenic bowel dysfunction, resulting in failure to contain stool and thus fecal incontinence.[19] This affects the bowel similarly to a spinal cord injury affecting the lower motor neuron resulting in a flaccid unreactive rectal wall and means the anal sphincter doesn't contract and close therefore leading to stool leakage.[18] Many patients with spina bifida also have hydrocephalus.[20] Less-recent research implies that intellectual deficits that may result from hydrocephalus may contribute to faecal incontinence.[21]

Additional complications that accompany neurogenic bowel dysfunction in individuals with spina bifida are likely to include urinary incontinence, urinary tract infections, shunt malfunction, potential for skin breakdown, hemorrhoids, and anal fissures. When individuals with Spina Bifida are not able to develop and maintain a bowel management program, they face challenges with finding and keeping a job, social isolation, and report a decreased quality of life.[22] [23][24]

Multiple sclerosis

[edit]There are a variety of symptoms associated with multiple sclerosis that are all caused by a loss of myelin, the insulating layer surrounding the neurons (nerve cells). This means the nerve signals are interrupted and are slower. This causes muscle contractions to be irregular and fewer, resulting in an increased colon transit time.[14] The feces stay in the colon for a longer period of time, meaning that more water is absorbed. This leads to harder stools and therefore increases the symptoms of constipation. This neurological problem can also result in reduced sensation of rectal filling and weakness of the anal sphincter because of weak muscular contraction so can cause stool leakage.[14] In patients with multiple sclerosis, constipation and fecal incontinence often coexist, and they can be acute, chronic or intermittent due to the fluctuating pattern of MS.[5]

Brain lesion

[edit]Damage to the defecation centre within the medulla oblongata of the brain can lead to bowel dysfunction. A stroke or acquired brain injury may lead to damage to this centre in the brain. Damage to the defecation centre can lead to a loss of coordination between rectal and anal contractions and also a loss of awareness of the need to defecate.[14]

Parkinson's disease

[edit]This condition differs as it affects both the extrinsic and enteric nervous systems due to the decreased dopamine levels in both. This results in less smooth muscle contraction of the colon, increasing the colon transit time.[14] The reduced dopamine levels also causes dystonia of the striated muscles of the pelvic floor and external anal sphincter. This explains how Parkinson's disease can lead to constipation.[16][non-primary source needed]

Diabetes mellitus

[edit]Twenty percent of people with diabetes mellitus experience fecal incontinence due to irreversible autonomic neuropathy. This is due to the high blood glucose levels over time damaging the nerves, which can lead to impaired rectal sensation.[14]

Mechanism

[edit]There are different types of neurons involved in innervating the lower GI tract these include: the enteric nervous system; located within the wall of the gut, and the extrinsic nervous system; comprising sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation.[3] The enteric nervous system directly controls the gut motility, whereas the extrinsic nerve pathways influence gut contractility indirectly through modifying this enteric innervation.[3] In almost all cases of neurogenic bowel dysfunction it is the extrinsic nervous supply affected and the enteric nervous supply remains intact. The only exception is Parkinson's disease, as this can affect both the enteric and extrinsic innervation.[14]

Defecation involves conscious and subconscious processes, when the extrinsic nervous system is damaged either of these can be affected. Conscious processes are controlled by the somatic nervous system, these are voluntary movements for example the contraction of the striated muscle of the external anal sphincter is instructed to do so by the brain, which sends signals along the nerves innervating this muscle.[25][26] Subconscious processes are controlled by the autonomic nervous system; these are involuntary movements such as contraction of the smooth muscle of the internal anal sphincter or the colon. The autonomic nervous system also provides sensory information; this could be about the level of distension within the colon or rectum.[25][26]

Diagnosis

[edit]

In order to correctly manage neurogenic bowel dysfunction it is important to accurately diagnose it. This can be done by a variety of methods, the most commonly used would be taking a clinical history and carrying out physical examinations which may include: abdominal, neurological and rectal examinations.[27] Patients may use the Bristol Stool Chart to help them describe and characterise the morphological features of their stool, this is useful as it gives an indication of the transit time.[28][non-primary source needed] An objective method used to evaluate the motility of the colon and help with diagnosis is the colon transit time.[29][non-primary source needed] Another helpful test to diagnose this condition may be an abdominal X-ray as this can show the distribution of feces and show any abnormalities with the colon, for example a megacolon.[16][non-primary source needed]

Management

[edit]Management and treatment for neurogenic bowel dysfunction depends on symptoms and biomedical diagnosis for cause of the condition.[16] The goal of bowel management is to achieve continence without constipation, and to improve the individual's quality of life, including opportunities for work and social connections.[30]

General practitioners have traditionally referred patients to gastroenterologists to manage neurogenic bowel dysfunction, but some researchers and specialists in the care of individuals with spina bifida point to the value of monitoring by multiple specialists and providers.[31] Research has been conducted on a variety of therapy and treatments for neurogenic bowel dysfunction, including: diet modification, laxatives, magnetic and electrical stimulation, manual evacuation of feces and abdominal massage, transanal irrigation, and various types of enema programs.[32][33]

In patients with spina bifida, researchers suggest beginning with the least to most invasive procedures.[33]

Efficacy studies for pulsed irrigation evacuation with PIEMED demonstrated favorable results, removing stool of 98% of patients who used it for ineffective bowel routine, symptomatic impaction, or asymptomatic impaction.[34] In the most severe of cases of neurogenic bowel dysfunction induced fecal impaction, surgical interventions like colostomy are used to disrupt the dense mass of stool.[35][36] However, there is a question whether comparative studies of PIE in individuals predisposed to fecal impaction demonstrate its value in including it in standard bowel management regimens in patients with neurogenic bowel.[37][38][34][39][40][41]

See also

[edit]External Links

[edit]- Lifespan Bowel Management Protocol

- Bowel Management presentations - Spina Bifida Association YouTube playlist

References

[edit]- ^ "Sample records for neurogenic bowel dysfunction". science.gov. Science.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-09-29. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

- ^ Emmanuel, A (2010-02-09). "Review of the efficacy and safety of transanal irrigation for neurogenic bowel dysfunction". Spinal Cord. 48 (9): 664–673. doi:10.1038/sc.2010.5. PMID 20142830.

- ^ a b c Brookes, SJ; Dinning, PG; Gladman, MA (December 2009). "Neuroanatomy and physiology of colorectal function and defaecation: from basic science to human clinical studies". Neurogastroenterol Motil. 21: 9–19. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01400.x. PMID 19824934. S2CID 33885542.

- ^ a b Palit, Somnath; Lunniss, Peter J.; Scott, S. Mark (2012-02-26). "The Physiology of Human Defecation". Dig Dis Sci. 57 (6): 1445–1464. doi:10.1007/s10620-012-2071-1. PMID 22367113. S2CID 25173457.

- ^ a b c d Krogh, K; Christensen, P; Laurberg, S (June 2001). "Colorectal symptoms in patients with neurological diseases". Acta Neurol Scand. 103 (6): 335–343. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.103006335.x. PMID 11421845. S2CID 28090580.

- ^ a b c Qi, Zhengyan; Middleton, James W; Malcolm, Allison (2018-08-29). "Bowel Dysfunction in Spinal Cord Injury". Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 20 (10): 47. doi:10.1007/s11894-018-0655-4. PMID 30159690. S2CID 52129284.

- ^ Nielsen, S D; Faaborg, P M; Christensen, P; Krogh, K; Finnerup, N B (2016-08-09). "Chronic abdominal pain in long-term spinal cord injury: a follow-up study". Spinal Cord. 55 (3): 290–293. doi:10.1038/sc.2016.124. PMID 27502843.

- ^ Ng, Clinton; Prott, Gillian; Rutkowski, Susan; Li, Yueming; Hansen, Ross; Kellow, John; Malcolm, Allison (2005). "Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Spinal Cord Injury: Relationships With Level of Injury and Psychologic Factors". Dis Colon Rectum. 48 (8): 1562–1568. doi:10.1007/s10350-005-0061-5. PMID 15981066. S2CID 22026816.

- ^ Coggrave, M; Norton, C; Wilson-Barnett, J (2008-11-18). "Management of neurogenic bowel dysfunction in the community after spinal cord injury: a postal survey in the United Kingdom". Spinal Cord. 47 (4): 323–333. doi:10.1038/sc.2008.137. PMID 19015665.

- ^ a b Gulick, EE (September 2022). "Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction Over the Course of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review". International Journal of MS Care. 24 (5): 209–217. doi:10.7224/1537-2073.2021-007. PMC 9461721. PMID 36090242.

- ^ Krogh, K; Christensen, P; Laurberg, S (June 2001). "Colorectal symptoms in patients with neurological diseases". Acta Neurol Scand. 103 (6): 335–343. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.103006335.x. PMID 11421845. S2CID 28090580.

- ^ Wiener, John; Suson, Kristina; Castillo, Jonathan; Routh, Jonathan; Tanaka, Stacy; Liu, Tiebin; Ward, Elisabeth; Thibadeau, Judy; Joseph, David (2017-12-11). Brei, Timothy; Houtrow, Amy (eds.). "Bowel management and continence in adults with spina bifida: Results from the National Spina Bifida Patient Registry 2009–15". Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine. 10 (3–4): 335–343. doi:10.3233/PRM-170466. PMC 6660830. PMID 29125526.

- ^ Branagan, G; Tromans, A; Finnis, D (2003). "Effect of stoma formation on bowel care and quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury". Spinal Cord. 41 (12): 680–683. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3101529. PMID 14639447.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pellatt, Glynis Collis (2008). "Neurogenic continence. Part 1: pathophysiology and quality of life". Br J Nurs. 17 (13): 836–841. doi:10.12968/bjon.2008.17.13.30534. PMID 18856146.

- ^ a b Cotterill, Nikki; Madersbacher, Helmut; Wyndaele, Jean J.; Apostolidis, Apostolos; Drake, Marcus J.; Gajewski, Jerzy; Heesakkers, John; Panicker, Jalesh; Radziszewski, Piotr (2017-06-22). "Neurogenic bowel dysfunction: Clinical management recommendations of the Neurologic Incontinence Committee of the Fifth International Consultation on Incontinence 2013". Neurourol Urodyn. 37 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1002/nau.23289. PMID 28640977. S2CID 206304249.

- ^ a b c d den Braber-Ymker, Marjanne; Lammens, Martin; van Putten, Michel J.A.M.; Nagtegaal, Iris D. (2017-01-06). "The enteric nervous system and the musculature of the colon are altered in patients with spina bifida and spinal cord injury". Virchows Archiv. 470 (2): 175–184. doi:10.1007/s00428-016-2060-4. PMC 5306076. PMID 28062917.

- ^ Kelly, Maryellen S.; Wiener, John S.; Liu, Tiebin; Patel, Priya; Castillo, Heidi; Castillo, Jonathan; Dicianno, Brad E.; Jasien, Joan; Peterson, Paula; Routh, Jonathan C.; Sawin, Kathleen; Sherburne, Eileen; Smith, Kathryn; Taha, Asma; Worley, Gordon (2020-12-22). Brei, Timothy; Castillo, Heidi; Castillo, Jonathan (eds.). "Neurogenic bowel treatments and continence outcomes in children and adults with myelomeningocele". Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine. 13 (4): 685–693. doi:10.3233/PRM-190667. PMC 8776357. PMID 33325404.

- ^ a b Pellatt, Glynis Collis (2008). "Neurogenic continence. Part 1: pathophysiology and quality of life". Br J Nurs. 17 (13): 836–841. doi:10.12968/bjon.2008.17.13.30534. PMID 18856146.

- ^ Dicianno, Brad E.; Beierwaltes, Patricia; Dosa, Nienke; Raman, Lisa; Chelliah, Jerome; Struwe, Sara; Panlener, Juanita; Brei, Timothy J. (April 2020). "Scientific methodology of the development of the Guidelines for the Care of People with Spina Bifida: An initiative of the Spina Bifida Association". Disability and Health Journal. 13 (2): 100816. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.06.005. ISSN 1936-6574. PMID 31248776.

- ^ Kshettry, Varun R.; Kelly, Michael L.; Rosenbaum, Benjamin P.; Seicean, Andreea; Hwang, Lee; Weil, Robert J. (June 2014). "Myelomeningocele: surgical trends and predictors of outcome in the United States, 1988–2010: Clinical article". Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics. 13 (6): 666–678. doi:10.3171/2014.3.PEDS13597. ISSN 1933-0707. PMID 24702620.

- ^ Krogh, K; Christensen, P; Laurberg, S (June 2001). "Colorectal symptoms in patients with neurological diseases". Acta Neurol Scand. 103 (6): 335–343. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.103006335.x. PMID 11421845. S2CID 28090580.

- ^ Burns, Anthony S.; St-Germain, Daphney; Connolly, Maureen; Delparte, Jude J.; Guindon, Andréanne; Hitzig, Sander L.; Craven, B. Catharine (January 2015). "Phenomenological Study of Neurogenic Bowel From the Perspective of Individuals Living With Spinal Cord Injury". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 96 (1): 49–55.e1. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.07.417. ISSN 0003-9993. PMID 25172370.

- ^ Choi, Eun Kyoung; Im, Young Jae; Han, Sang Won (May 2017). "Bowel Management and Quality of Life in Children With Spina Bifida in South Korea". Gastroenterology Nursing. 40 (3): 208–215. doi:10.1097/SGA.0000000000000135. ISSN 1042-895X. PMID 26560901.

- ^ Pardee, Connie; Bricker, Diedre; Rundquist, Jeanine; MacRae, Christi; Tebben, Cherisse (May 2012). "Characteristics of Neurogenic Bowel in Spinal Cord Injury and Perceived Quality of Life". Rehabilitation Nursing. 37 (3): 128–135. doi:10.1002/rnj.00024. ISSN 0278-4807. PMID 22549630.

- ^ a b Preziosi, Giuseppe; Emmanuel, Anton (2009). "Neurogenic bowel dysfunction: pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and treatment". Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 3 (4): 417–423. doi:10.1586/egh.09.31. PMID 19673628. S2CID 37109139.

- ^ a b Awad, Richard A (2011). "Neurogenic bowel dysfunction in patients with spinal cord injury, myelomeningocele, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 17 (46): 5035–48. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i46.5035. PMC 3235587. PMID 22171138.

- ^ Krogh, Klaus; Christensen, Peter (2009). "Neurogenic colorectal and pelvic floor dysfunction". Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 23 (4): 531–543. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2009.04.012. PMID 19647688.

- ^ Amarenco, G. (2014). "Bristol Stool Chart : étude prospective et monocentrique de " l'introspection fécale " chez des sujets volontaires". Progrès en Urol. 24 (11): 708–713. doi:10.1016/j.purol.2014.06.008. PMID 25214452.

- ^ Faaborg, P M; Christensen, P; Rosenkilde, M; Laurberg, S; Krogh, K (2010-11-23). "Do gastrointestinal transit times and colonic dimensions change with time since spinal cord injury?". Spinal Cord. 49 (4): 549–553. doi:10.1038/sc.2010.162. PMID 21102573.

- ^ Beierwaltes, Patricia; Church, Paige; Gordon, Tiffany; Ambartsumyan, Lusine (2020-12-22). Brei, Timothy; Castillo, Heidi; Castillo, Jonathan (eds.). "Bowel function and care: Guidelines for the care of people with spina bifida". Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine. 13 (4): 491–498. doi:10.3233/PRM-200724. PMC 7838963. PMID 33252093.

- ^ Kelly, Maryellen S.; Stout, Jennifer; Wiener, John S. (2021-12-23). "Who is managing the bowels? A survey of clinical practice patterns in spina bifida clinics". Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine. 14 (4): 675–679. doi:10.3233/PRM-201512. PMID 34864702.

- ^ Kelly, Maryellen S. (2019). "Malone Antegrade Continence Enemas vs. Cecostomy vs. Transanal Irrigation—What Is New and How Do We Counsel Our Patients?". Current Urology Reports. 20 (8) 41. doi:10.1007/s11934-019-0909-1. ISSN 1527-2737. PMID 31183573.

- ^ a b Kelly, Maryellen S.; Sherburne, Eileen; Kerr, Joy; Payne, Colleen; Dorries, Heather; Beierwaltes, Patricia; Guerro, Adam; Thibadeau, Judy (2023-12-26). Brei, Timothy; Castillo, Heidi; Castillo, Jonathan; Thibadeau, Judy (eds.). "Release and highlights of the Lifespan Bowel Management Protocol produced for clinicians who manage neurogenic bowel dysfunction in individuals with spina bifida". Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine. 16 (4): 675–677. doi:10.3233/PRM-230060. PMC 10789357. PMID 38160374.

- ^ a b Gramlich, T.; Puet, T. (August 1998). "Long-term safety of pulsed irrigation evacuation (PIE) use with chronic bowel conditions". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 43 (8): 1831–1834. doi:10.1023/a:1018808408880. ISSN 0163-2116. PMID 9724176. S2CID 35212840.

- ^ Ray, Kausik; McFall, Malcolm (April 2010). "Large bowel enema through colostomy with a Foley catheter: a simple and effective technique". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 92 (3): 263. doi:10.1308/rcsann.2010.92.3.263. ISSN 1478-7083. PMC 3080060. PMID 20425893.

- ^ Facts about Neurogenic Bladder Treatment

- ^ Preziosi, Giuseppe; Emmanuel, Anton (2009). "Neurogenic bowel dysfunction: pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and treatment". Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 3 (4): 417–423. doi:10.1586/egh.09.31. PMID 19673628. S2CID 37109139.

- ^ Beierwaltes, Patricia; Church, Paige; Gordon, Tiffany; Ambartsumyan, Lusine (2020-12-22). Brei, Timothy; Castillo, Heidi; Castillo, Jonathan (eds.). "Bowel function and care: Guidelines for the care of people with spina bifida". Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine. 13 (4): 491–498. doi:10.3233/PRM-200724. PMC 7838963. PMID 33252093.

- ^ McClurg, Doreen; Norton, Christine (2016-07-27). "What is the best way to manage neurogenic bowel dysfunction?". BMJ. 354: i3931. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3931. PMID 27815246. S2CID 28028731. Archived from the original on 2018-09-29. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

- ^ Kelly, Maryellen S. (August 2019). "Malone Antegrade Continence Enemas vs. Cecostomy vs. Transanal Irrigation—What Is New and How Do We Counsel Our Patients?". Current Urology Reports. 20 (8) 41. doi:10.1007/s11934-019-0909-1. ISSN 1527-2737. PMID 31183573.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Coggrave, Maureen; Norton, Christine (2013-12-18), The Cochrane Collaboration (ed.), "Management of faecal incontinence and constipation in adults with central neurological diseases", Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12), Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: CD002115, doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002115.pub4, PMID 24347087, retrieved 2025-06-26