Nova classification

The Nova classification (Portuguese: nova classificação, 'new classification') is a framework for grouping edible substances based on the extent and purpose of food processing applied to them. Researchers at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, proposed the system in 2009.[1]

Nova classifies food into four groups:

- Unprocessed or minimally processed foods

- Processed culinary ingredients

- Processed foods

- Ultra-processed foods[2]

The system has been used worldwide in nutrition and public health research, policy, and guidance as a tool for understanding the health implications of different food products.[3]

History

[edit]The Nova classification grew out of the research of Carlos Augusto Monteiro. Born in 1948 into a family straddling the divide between poverty and relative affluence in Brazil, Monteiro's journey began as the first member of his family to attend university.[4] His early research in the late 1970s focused on malnutrition, reflecting the prevailing emphasis in nutrition science of the time.[5][6] In the mid-1990s, Monteiro observed a significant shift in Brazil's dietary landscape marked by a rise in obesity rates among economically disadvantaged populations, while more affluent areas saw declines. This transformation led him to explore dietary patterns holistically, rather than focusing solely on individual nutrients. Employing statistical methods, Monteiro identified two distinct eating patterns in Brazil: one rooted in traditional foods like rice and beans and another characterized by the consumption of highly processed products.[7]

The classification's name is from the title of the original scientific article in which it was published, 'A new classification of foods' (Portuguese: Uma nova classificação de alimentos).[8] The idea of applying this as the classification's name is credited to Jean-Claude Moubarac of the Université de Montréal.[4] The name is often styled in capital letters, NOVA, but it is not an acronym.[9] Recent scientific literature leans towards writing the name as Nova, including papers written with Monteiro's involvement.[10][11][12]

Nova food processing groups

[edit]The Nova framework presents four food groups, defined according the nature, extent, and purpose of industrial food processing applied.[9] Databases such as Open Food Facts provide Nova classifications for commercial products based on analysis of their categories and ingredients.[13] Assigning foods to these categories is most straightforward if information is available on food preparation and composition.[10]

The classification's attention to social aspects of food give it an intuitive character. This makes it an effective communication tool in public health promotion, since it builds on consumers' established perceptions.[14][15] At the same time, this characteristic has led some scientists to question whether Nova is suitable for scientific control.[16] By contrast, researchers have successfully developed a quantitative definition for hyperpalatable food.[17] Both proponents and opponents of Nova 'agree that food processing vitally affects human health', but not on its definition of ultra-processing.[18][19][20]

Nova is an open classification that refines its definitions gradually through new scientific publications rather than through a central advisory board.[21]

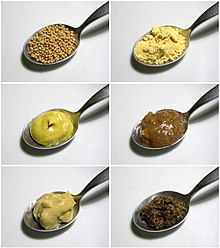

Group 1: Unprocessed or minimally processed foods

[edit]

Unprocessed foods are the edible parts of plants, animals, algae and fungi along with water.[citation needed]

This group also includes minimally processed foods, which are unprocessed foods modified through industrial methods such as the removal of unwanted parts, crushing, drying, fractioning, grinding, pasteurization, non-alcoholic fermentation, freezing, and other preservation techniques that maintain the food's integrity and do not introduce salt, sugar, oils, fats, or other culinary ingredients. Additives are absent in this group.[2]

Examples include fresh or frozen fruits and vegetables, grains, legumes, fresh meat, eggs, milk, plain yogurt, and crushed spices.[2]

Group 2: Processed culinary ingredients

[edit]

Processed culinary ingredients are derived from group 1 foods or else from nature by processes such as pressing, refining, grinding, milling, and drying. It also includes substances mined or extracted from nature. These ingredients are primarily used in seasoning and cooking group 1 foods and preparing dishes from scratch. They are typically free of additives, but some products in this group may include added vitamins or minerals, such as iodized salt.[citation needed]

Examples include oils produced through crushing seeds, nuts, or fruits (such as olive oil), salt, sugar, vinegar, starches, honey, syrups extracted from trees, butter, and other substances used to season and cook.[2]

Group 3: Processed foods

[edit]

Processed foods are relatively simple food products produced by adding processed culinary ingredients (group 2 substances) such as salt or sugar to unprocessed (group 1) foods.[2]

Processed foods are made or preserved through baking, boiling, canning, bottling, and non-alcoholic fermentation. They often use additives to enhance shelf life, protect the properties of unprocessed food, prevent the spread of microorganisms, or making them more enjoyable.[2]

Examples include cheese, canned vegetables, salted nuts, fruits in syrup, and dried or canned fish. Breads, pastries, cakes, biscuits, snacks, and some meat products fall into this group when they are made predominantly from group 1 foods with the addition of group 2 ingredients.[2]

Group 4: Ultra-processed foods

[edit]

The most recent overview of Nova published with Monteiro defines ultra-processed food as follows:

Industrially manufactured food products made up of several ingredients (formulations) including sugar, oils, fats and salt (generally in combination and in higher amounts than in processed foods) and food substances of no or rare culinary use (such as high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils, modified starches and protein isolates). Group 1 foods are absent or represent a small proportion of the ingredients in the formulation. Processes enabling the manufacture of ultra-processed foods include industrial techniques such as extrusion, moulding and pre-frying; application of additives including those whose function is to make the final product palatable or hyperpalatable such as flavours, colourants, non-sugar sweeteners and emulsifiers; and sophisticated packaging, usually with synthetic materials. Processes and ingredients here are designed to create highly profitable (low-cost ingredients, long shelf-life, emphatic branding), convenient (ready-to-(h)eat or to drink), tasteful alternatives to all other Nova food groups and to freshly prepared dishes and meals. Ultra-processed foods are operationally distinguishable from processed foods by the presence of food substances of no culinary use (varieties of sugars such as fructose, high-fructose corn syrup, 'fruit juice concentrates', invert sugar, maltodextrin, dextrose and lactose; modified starches; modified oils such as hydrogenated or interesterified oils; and protein sources such as hydrolysed proteins, soya protein isolate, gluten, casein, whey protein and 'mechanically separated meat') or of additives with cosmetic functions (flavours, flavour enhancers, colours, emulsifiers, emulsifying salts, sweeteners, thickeners and anti-foaming, bulking, carbonating, foaming, gelling and glazing agents) in their list of ingredients.[10]

The Nova definition of ultra-processed food does not comment on the nutritional content of food and is not intended to be used for nutrient profiling.[22]

Impact on public health

[edit]The Nova classification has been increasingly used to evaluate the relationship between the extent of food processing and health outcomes. Epidemiological studies have linked the consumption of ultra-processed foods with obesity, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, depression, and various types of cancer.[23][24]

Researchers conclude that the creation of ultra-processed foods is primarily motivated by economic considerations within the food industry. The processes and ingredients used for these foods are specifically designed to maximize profitability by incorporating low-cost ingredients, ensuring long shelf-life, and emphasizing branding.[25] Furthermore, ultra-processed foods are engineered to be convenient and hyperpalatable, making them a potential replacement for other food groups within the Nova classification, particularly unprocessed or minimally processed foods.[2] As a result, researchers and public health campaigners are using the Nova classification as a means to enhance both human health outcomes and food sustainability.[26]

The system has also been used to inform food and nutrition policies in several countries and international organizations. For example, the Pan American Health Organization has adopted the Nova classification in its dietary guidelines.[27]

In 2014, the Ministry of Health of Brazil published new dietary guidelines based in part on Nova, crediting Carlos Monteiro as the coordinator. These recommend a 'golden rule', 'Always prefer natural or minimally processed foods and freshly made dishes and meals to ultra-processed foods.' They also set out recommendations corresponding to the Nova groups:[28][29]

- Make natural or minimally processed foods, in great variety, mainly of plant origin, and preferably produced with agro-ecological methods, the basis of your diet.

- Use oils, fats, salt and sugar in small amounts for seasoning and cooking foods and to create culinary preparations.

- Limit the use of processed foods, consuming them in small amounts as ingredients in culinary preparations or as part of meals based on natural or minimally processed foods.

- Avoid ultra-processed products.[9]

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations recognized these as the first national dietary guidelines to emphasize 'the social and economic aspects of sustainability, advising people to be wary of advertising, for example, and to avoid ultra-processed foods that are not only bad for health but are seen to undermine traditional food cultures. They stand in contrast to the largely environmental definition of sustainability adopted in the other guidelines.'[30][31]

The Nova classification does not comment on the nutritional value of food and can be combined with a labelling system such as Nutri-Score to provide comprehensive guidance on healthy eating.[13][32]

References

[edit]- ^ Monteiro, Carlos A. (2009-05-01). "Nutrition and health. The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing". Public Health Nutrition. 12 (5): 729–731. doi:10.1017/S1368980009005291. ISSN 1475-2727. PMID 19366466. S2CID 42136316.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Monteiro, Carlos A.; Cannon, Geoffrey; Levy, Renata B; Moubarac, Jean-Claude; Louzada, Maria L. C.; Rauber, Fernanda; Khandpur, Neha; Cediel, Gustavo; Neri, Daniela; Martinez-Steele, Euridice; Baraldi, Larissa G.; Jaime, Patricia C. (2019). "Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them". Public Health Nutrition. 22 (5): 936–941. doi:10.1017/S1368980018003762. ISSN 1368-9800. PMC 10260459. PMID 30744710.

- ^ Monteiro, Carlos Augusto; Cannon, Geoffrey; Lawrence, Mark; da Costa Louzada, Maria Laura; Machado, Priscila Pereira (2019). Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the NOVA classification system. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-131701-3.

- ^ a b van Tulleken, Chris (2023). Ultra-processed people: Why do we all eat stuff that isn't food ... and why can't we stop?. London: Cornerstone Press. ISBN 978-1-5291-6023-9.

- ^ Monteiro, Carlos Augusto; Réa, Marina Ferreira (1977-09-01). "A classificação antropométrica como instrumento de investigação epidemiológica da desnutrição protéico-calórica". Revista de Saúde Pública (in Portuguese). 11 (3): 353–361. doi:10.1590/S0034-89101977000300007. ISSN 0034-8910.

- ^ Monteiro, Carlos Augusto (1979-02-20). O peso ao nascer no município de São Paulo: Impacto sobre os níveis de mortalidade na infância (Doutorado em Nutrição thesis) (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo. doi:10.11606/t.6.2016.tde-28072016-170319.

- ^ Wang, Youfa; Monteiro, Carlos; Popkin, Barry M. (2002-06-01). "Trends of obesity and underweight in older children and adolescents in the United States, Brazil, China, and Russia". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 75 (6): 971–977. doi:10.1093/ajcn/75.6.971. PMID 12036801.

- ^ Monteiro, Carlos Augusto; Levy, Renata Bertazzi; Claro, Rafael Moreira; de Castro, Inês Rugani Ribeiro; Cannon, Geoffrey (2010). "A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing". Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 26 (11): 2039–2049. doi:10.1590/S0102-311X2010001100005. ISSN 0102-311X. PMID 21180977.

- ^ a b c Monteiro, Carlos Augusto; Cannon, Geoffrey; Moubarac, Jean-Claude; Levy, Renata Bertazzi; Louzada, Maria Laura C; Jaime, Patrícia Constante (2018). "The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing". Public Health Nutrition. 21 (1): 5–17. doi:10.1017/S1368980017000234. ISSN 1368-9800. PMC 10261019. PMID 28322183.

- ^ a b c Martinez-Steele, Euridice; Khandpur, Neha; Batis, Carolina; Bes-Rastrollo, Maira; Bonaccio, Marialaura; Cediel, Gustavo; Huybrechts, Inge; Juul, Filippa; Levy, Renata B.; da Costa Louzada, Maria Laura; Machado, Priscila P.; Moubarac, Jean-Claude; Nansel, Tonja; Rauber, Fernanda; Srour, Bernard (2023-06-01). "Best practices for applying the Nova food classification system". Nature Food. 4 (6): 445–448. doi:10.1038/s43016-023-00779-w. ISSN 2662-1355. PMID 37264165. S2CID 259024679.

- ^ Huybrechts, Inge; Rauber, Fernanda; Nicolas, Geneviève; Casagrande, Corinne; Kliemann, Nathalie; Wedekind, Roland; Biessy, Carine; Scalbert, Augustin; Touvier, Mathilde; Aleksandrova, Krasimira; Jakszyn, Paula; Skeie, Guri; Bajracharya, Rashmita; Boer, Jolanda M. A.; Borné, Yan (2022-12-16). "Characterization of the degree of food processing in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition: Application of the Nova classification and validation using selected biomarkers of food processing". Frontiers in Nutrition. 9. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.1035580. ISSN 2296-861X. PMC 9800919. PMID 36590209.

- ^ Santos, Francine Silva dos; Steele, Eurídice Martinez; Costa, Caroline dos Santos; Gabe, Kamila Tiemman; Leite, Maria Alvim; Claro, Rafael Moreira; Touvier, Mathilde; Srour, Bernard; da Costa Louzada, Maria Laura; Levy, Renata Bertazzi; Monteiro, Carlos Augusto (2023-07-31). "Nova diet quality scores and risk of weight gain in the NutriNet-Brasil cohort study". Public Health Nutrition. 26 (11): 2366–2373. doi:10.1017/S1368980023001532. ISSN 1368-9800. PMC 10641608. PMID 37522809. S2CID 260333016.

- ^ a b Romero Ferreiro, Carmen; Lora Pablos, David; Gómez de la Cámara, Agustín (2021-08-13). "Two dimensions of nutritional value: Nutri-Score and NOVA". Nutrients. 13 (8): 2783. doi:10.3390/nu13082783. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 8399905. PMID 34444941.

- ^ Hässig, Alenica; Hartmann, Christina; Sanchez-Siles, Luisma; Siegrist, Michael (2023-08-01). "Perceived degree of food processing as a cue for perceived healthiness: The NOVA system mirrors consumers' perceptions". Food Quality and Preference. 110: 104944. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2023.104944. hdl:20.500.11850/625580. ISSN 0950-3293. S2CID 259941132.

- ^ Ares, Gastón; Vidal, Leticia; Allegue, Gimena; Giménez, Ana; Bandeira, Elisa; Moratorio, Ximena; Molina, Verónika; Curutchet, María Rosa (2016-10-01). "Consumers' conceptualization of ultra-processed foods". Appetite. 105: 611–617. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2016.06.028. ISSN 0195-6663. PMID 27349706. S2CID 3554621.

- ^ Visioli, Francesco; Marangoni, Franca; Fogliano, Vincenzo; Rio, Daniele Del; Martinez, J. Alfredo; Kuhnle, Gunter; Buttriss, Judith; Ribeiro, Hugo Da Costa; Bier, Dennis; Poli, Andrea (2022-06-22). "The ultra-processed foods hypothesis: A product processed well beyond the basic ingredients in the package". Nutrition Research Reviews. 36 (2): 340–350. doi:10.1017/S0954422422000117. hdl:11577/3451280. ISSN 0954-4224. PMID 35730561. S2CID 249923737.

- ^ Fazzino, Tera L.; Rohde, Kaitlyn; Sullivan, Debra K. (2019-11-01). "Hyper-palatable foods: Development of a quantitative definition and application to the US Food System Database". Obesity. 27 (11): 1761–1768. doi:10.1002/oby.22639. hdl:1808/29721. ISSN 1930-7381. PMID 31689013. S2CID 207899275.

- ^ Monteiro, Carlos A.; Astrup, Arne (2022-12-01). "Does the concept of "ultra-processed foods" help inform dietary guidelines, beyond conventional classification systems? YES". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 116 (6): 1476–1481. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqac122. PMID 35670127.

- ^ Astrup, Arne; Monteiro, Carlos A. (2022-12-01). "Does the concept of "ultra-processed foods" help inform dietary guidelines, beyond conventional classification systems? NO". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 116 (6): 1482–1488. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqac123. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 35670128.

- ^ Astrup, Arne; Monteiro, Carlos A. (2022-12-01). "Does the concept of "ultra-processed foods" help inform dietary guidelines, beyond conventional classification systems? Debate consensus". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 116 (6): 1489–1491. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqac230. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 36253965.

- ^ Gibney, Michael J (2019-02-01). "Ultra-processed foods: Definitions and policy issues". Current Developments in Nutrition. 3 (2): nzy077. doi:10.1093/cdn/nzy077. PMC 6389637. PMID 30820487.

- ^ Lockyer, Stacey; Spiro, Ayela; Berry, Sarah; He, Jibin; Loth, Shefalee; Martinez-Inchausti, Andrea; Mellor, Duane; Raats, Monique; Sokolović, Milka; Vijaykumar, Santosh; Stanner, Sara (2023). "How do we differentiate not demonise – Is there a role for healthier processed foods in an age of food insecurity? Proceedings of a roundtable event". Nutrition Bulletin. 48 (2): 278–295. doi:10.1111/nbu.12617. ISSN 1471-9827. PMID 37164357. S2CID 258618401.

- ^ Lane, Melissa M.; Gamage, Elizabeth; Du, Shutong; Ashtree, Deborah N.; McGuinness, Amelia J.; Gauci, Sarah; Baker, Phillip; Lawrence, Mark; Rebholz, Casey M.; Srour, Bernard; Touvier, Mathilde; Jacka, Felice N.; O'Neil, Adrienne; Segasby, Toby; Marx, Wolfgang (2024-02-28). "Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses". BMJ. 384: e077310. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-077310. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 10899807. PMID 38418082.

- ^ Isaksen, Irja Minde; Dankel, Simon Nitter (2023-06-01). "Ultra-processed food consumption and cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical Nutrition. 42 (6): 919–928. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2023.03.018. ISSN 0261-5614. PMID 37087831. S2CID 257872002.

- ^ Touvier, Mathilde; Louzada, Maria Laura da Costa; Mozaffarian, Dariush; Baker, Phillip; Juul, Filippa; Srour, Bernard (2023-10-09). "Ultra-processed foods and cardiometabolic health: Public health policies to reduce consumption cannot wait". BMJ. 383: e075294. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075294. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 10561017. PMID 37813465.

- ^ Leite, Fernanda Helena Marrocos; Khandpur, Neha; Andrade, Giovanna Calixto; Anastasiou, Kim; Baker, Phillip; Lawrence, Mark; Monteiro, Carlos Augusto (2022-03-01). "Ultra-processed foods should be central to global food systems dialogue and action on biodiversity". BMJ Global Health. 7 (3): e008269. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008269. ISSN 2059-7908. PMC 8895941. PMID 35346976.

- ^ Monteiro, Carlos A.; Cannon, Geoffrey; Levy, Renata; Moubarac, Jean-Claude; Jaime, Patricia; Martins, Ana Paula; Canella, Daniela; Louzada, Maria; Parra, Diana (2016-01-07). "NOVA. The star shines bright". World Nutrition. 7 (1–3): 28–38. ISSN 2041-9775.

- ^ Ministry of Health of Brazil (2014). Dietary guidelines for the Brazilian population (PDF) (2 ed.). Brasília: Ministry of Health of Brazil. ISBN 978-85-334-2242-1.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization (2014). "Food-based dietary guidelines: Brazil". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- ^ Gonzalez Fischer, Carlos; Garnett, Tara (2016). Plates, pyramids, planet. Developments in national healthy and sustainable dietary guidelines: A state of play assessment. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-109222-4.

- ^ James-Martin, Genevieve; Baird, Danielle L.; Hendrie, Gilly A.; Bogard, Jessica; Anastasiou, Kim; Brooker, Paige G; Wiggins, Bonnie; Williams, Gemma; Herrero, Mario; Lawrence, Mark; Lee, Amanda J.; Riley, Malcolm D. (2022-12-01). "Environmental sustainability in national food-based dietary guidelines: A global review". The Lancet Planetary Health. 6 (12): e977 – e986. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(22)00246-7. ISSN 2542-5196. PMID 36495892. S2CID 254442810.

- ^ Bonaccio, Marialaura; Castelnuovo, Augusto Di; Ruggiero, Emilia; Costanzo, Simona; Grosso, Giuseppe; Curtis, Amalia De; Cerletti, Chiara; Donati, Maria Benedetta; Gaetano, Giovanni de; Iacoviello, Licia (2022-08-31). "Joint association of food nutritional profile by Nutri-Score front-of-pack label and ultra-processed food intake with mortality: Moli-sani prospective cohort study". BMJ. 378: e070688. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-070688. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 9430377. PMID 36450651.