Nucleariid

| Nucleariids | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nuclearia thermophila | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Opisthokonta |

| Clade: | Holomycota |

| Order: | Rotosphaerida Rainer 1968[2][3] |

| Family: | Nucleariidae Cann & Page 1979[1] |

| Genera | |

| Diversity | |

| Around 50 species[4] | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

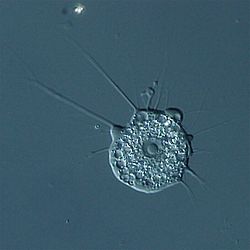

The nucleariids, or nucleariid amoebae, are a group of amoebae that compose the sister clade of the fungi. Together, they form the clade Holomycota. They are aquatic organisms found in freshwater and marine habitats, as well as in faeces. They are free-living phagotrophic predators that mostly consume algae and bacteria.

Nucleariids are characterized by simple, spherical or flattened single-celled bodies with filopodia (fine, thread-like pseudopods), covered by a mucous coat. They lack flagella and microtubules. Inside the cytoplasm of some species are endosymbiotic proteobacteria. Some species are naked, with only the mucous coat as cover, while others (known as 'scaled' nucleariids) have silica-based or exogenous particles of various shapes.

An exceptional nucleariid, Fonticula alba, develops multicellular fruting bodies (sorocarps) for spore dispersal. It is one of several cases of independently evolved multicellularity within Opisthokonta, the clade that houses both Holozoa (which includes animals) and Holomycota.

Initially, nucleariids were grouped with other filose amoebae (i.e., with filopodia) based on their superficial similarity. Silica-scaled and naked nucleariids were classified into separate families from one another, Pompholyxophryidae and Nucleariidae, respectively. Due to its nature as a slime mold, the genus Fonticula has also been classified separatedly, particularly with acrasids and other slime molds. With advancements in electron microscopy and molecular phylogenetics, the three groups were revealed to belong to the same clade as sister to the fungi. Due to lack of molecular data, the three groups are treated as one family, under the name of Nucleariidae.

Various conflicting systems of above-family classification exist for nucleariids, with older systems grouping them as a class Cristidiscoidea composed of two orders: one for Fonticula and another for the remaining species. Mycologists regard them as an independent kingdom of life, Nucleariae, with two phyla that mirror those two orders. They are generally accepted by protistologists as a single order Rotosphaerida, which is the oldest taxonomic name for these organisms.

Description

[edit]Nucleariids are single-celled amoebae that lack flagella and have radiating filopodia (i.e., thread-like pseudopodia). They have a spherical or sometimes flattened cell bodies[9] with one or few conspicuous nuclei, each with a prominent central nucleolus except for Fonticula and Parvularia: Parvularia can also have peripheral nucleoral material instead,[10] and Fonticula has an indistinct nucleolus. The cytoplasm contains multiple vacuoles, including food vesicles, contractile vacuoles in freshwater species, and lipid globules. They have relatively simple cells in comparison to other protists: they lack flagella, cytoplasmic microtubules,[a] extrusomes, and special organelles.[4] Exceptionally, some species contain endosymbiotic proteobacteria (most frequently members of the genus Rickettsia).[11]

Most nucleariids have some kind of mucous coat, with or without coverings. The coverings can be made with endogenous silica-based particles (known as idiosomes) or with exogenous particles (known as xenosomes).[4] These particles are developed into hollow siliceous scales or spines.[12] The mucous coat itself—sometimes called glycocalyx—is enigmatic, as it can be present or absent in the same organism depending on the conditions. It appears to be made of one or two layers fibrous material running parallel to the cell membrane, and it often houses bacterial ectosymbionts. Surrounding the cell periphery, the characteristic hyaline (i.e., transparent) filopodia are found, originating from any point of the cell surface, sometimes branching or tapering but are never stiff or anastomosing (fusing with one another). Unlike Heliozoa, these filopodia are not supported by microtubules and do not contain extrusomes.[4]

Most species develop a resting cyst during their life cycle consisting of a smooth spherical cell covered by one or more thick layers of a translucent material.[4]

Ecology

[edit]Nucleariids thrive in water bodies worldwide. Most live in a variety of freshwater environments, including hot spring waters of around 30 °C.[13] Others are found in marine environments (e.g., Lithocolla), and others inhabit faeces (Fonticula).[4]

Nucleariids are free-living phagotrophs, and preferably consume cyanobacteria and other algae.[9] Small-celled species like those of Parvularia and Fonticula feed on small bacteria, while larger cells such as Nuclearia, Pompholyxophrys and Lithocolla can also feed on detritus and unicellular eukaryotic algae (e.g., diatoms). All of them are slow-paced grazers[14] that probably grow in response to the availability of their food sources, such as after algal blooms.[4]

Evolution

[edit]

Nucleariids are the closest relatives of fungi,[15] together forming the clade Holomycota.[16][17][7][4] This clade is, in turn, closely related to Holozoa, the clade containing animals and their closest protist relatives. Together, they form the clade Opisthokonta. After animals and fungi, nucleariids include the third known occurrence of multicellularity among opisthokonts:[b] the species Fonticula alba, a type of slime mold, capable of aggregative multicellular fruiting that develops sorocarps (stalks with masses of spores) for dispersal. The existence of Fonticula alba suggests that opisthokonts have a great propensity toward multicellularity.[16]

| Obazoa |

| ||||||||||||||||||

Nucleariids are unique within their greater evolutionary context. Apusomonads (relatives of opisthokonts), holozoans and fungi all evolved from ancestors that were single-celled phagotrophic flagellates. Opisthokonts, in particular, are characterized by a single posterior flagellum. Even the most basal-branching fungi (aphelids, rozellids and microsporidia)[c] are single-celled flagellates that prey on other eukaryotes.[18] The last common ancestor of nucleariids, however, had lost the opisthokont flagellum and its cell polarity, and had gained the characteristic mucous coat.[4] The presence of filopodia is more common among opisthokonts, shared with aphelids[18] and most holozoans.[20]

Classification

[edit]History

[edit]The history of the classification of nucleariids is full of incongruence between morphology and molecular phylogeny. Toward the end of the 19th century, most nucleariid species had already been described, and were classified with other naked or scaled filose amoebae.[21][4] During the second half of the 20th century, naturalist Heinrich Rainer described a subgroup of heliozoans, Rotosphaeridia, to accommodate non-flagellated, scaled, filose amoebae without axopodia (the nucleariids Pompholyxophrys, Pinaciophora, Lithocolla and Rhabdiophrys).[2]

Protozoologists John P. Cann and Frederick C. Page established the family Nucleariidae to include the naked genera Nuclearia, Gobiella and Nucleosphaerium[1] (later synonymized with Nuclearia).[22] Through studies of their fine cellular ultrastructure via transmission electron microscopy, the order Cristidiscoidida was established within the class Filosea, to accommodate both families Nucleariidae and the silica-scaled Pompholyxophryidae (e.g., Pompholyxophrys, Pinaciophora and Rhabdiophrys), because they all shared disc-shaped mitochondrial cristae as a common characteristic (i.e., they were discicristate).[5][23][4]

The genus Fonticula was continually excluded, as it was considered an acrasid[8] or a slime mold,[24] until 1993, when protozoologist Thomas Cavalier-Smith created the subclass Cristidiscoidia to house two orders: Nucleariida (with Nucleariidae and Pompholyxophryidae) and Fonticulida (with Fonticulidae).[6][4] However, he later considered scaled nucleariids (Pompholyxophryidae) as members of the Cercozoa, completely separate from naked ones,[25] but this is no longer accepted.[11] In a 1999 taxonomic revision by Kirill A. Mikrjukov, Cristidiscoidida was regarded as a junior synonym of Rotosphaerida, which finally united all discicristate filose amoebae. He also included Belonocystis[26] and Micronuclearia in this order,[27] which now are known to belong to Amoebozoa and CRuMs, respectively.[4]

At present, different conflicting classifications for nucleariids remain in use depending on the authors. Cavalier-Smith maintained his system through the years, using the name Cristidiscoidea as a class of his paraphyletic phylum Choanozoa, which included all protists most closely related to animals and fungi.[28] Mycologists have proposed a separate kingdom Nucleariae with lower ranks for Cavalier-Smith's two orders (phyla Nuclearida and Fonticulida, classes Nuclearidea and Fonticulidea), but without specifying their taxonomic composition.[7] Generally, protistologists prefer using the order Rotosphaerida instead, as it has priority over more recent names.[26][3][11] Most studies using the name Cristidiscoidea have only included Nuclearia or environmental sequences, while those using Rotosphaerida have been used when studying the scale-bearing amoebae and, more recently, the naked ones as well.[4]

At the family-level rank, although historically both Nucleariidae and Pompholyxophryidae have been used separately for naked and scale-bearing nucleariids respectively,[26] and Fonticulidae solely for Fonticula,[6] protistologists tend to use only Nucleariidae now,[23][4] as there is no clear evolutionary separation between the three families.[11]

Genera

[edit]Of all nucleariids, only a few have been isolated and molecularly analyzed.[11] Many genera remain as incertae sedis due to the lack of molecular data,[29] as it is difficult to confirm their evolutionary position other than by morphological similarity. The following is a list of nucleariid genera, including those that are at least suspected to be nucleariids (marked with an asterisk):[23][4]

- Elaeorhanis* Greef, 1873 (=Lithosphaerella Frenzel 1897; Estrella Frenzel 1897) – may also be related to Diplophrys, a member of the labyrinthulomycete order Amphitremida.[30]

- Fonticula Worley, Raper & Hohl 1979[8]

- Lithocolla Schulze 1874

- Nuclearia Cienkowski 1865 (=Nuclearella Frenzel 1897; Nuclearina Frenzel 1897; Nucleosphaerium Cann & Page 1979)

- Parvularia López-Escardó 2017[10]

- Pinaciophora* Greeff 1869 (=Pinacocystis Hertwig & Lesser 1874; Pinaciocystis Roskin 1929; Potamodiscus Gerloff 1968)[26]

- Pompholyxophrys Archer 1869 (=Hyalolampe Greeff 1869[26]

- Rabdiaster* Mikrjukov 1999[26]

- Rabdiophrys* Rainer 1968[2]

- Thomseniophora* Nicholls 2012[31]

- Vampyrellidium* Zopf 1885

Notes

[edit]- ^ The putative nucleariid genus Vampyrellidium has cytoplasmic microtubules, but the remaining ultrastructural traits have supported its placement among nucleariids.[4]

- ^ Excluding the colony formation found across holozoan protists, particularly choanoflagellates and ichthyosporeans, which can be considered multicellular to some degree.[16]

- ^ The aphelids, rozellids and microsporidia are sometimes interpreted as protists[18] instead of fungi,[7][19] depending on the authors.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Cann, J. P.; Page, F. C. (1979). "Nucleosphaerium tuckeri nov. gen. nov. sp. – a new freshwater filose amoeba without motile form in a new family Nucleariidae (Filosea: Aconchulinida) feeding by ingestion only". Archiv für Protistenkunde. 122 (3–4): 226–240. doi:10.1016/S0003-9365(79)80034-2.

- ^ a b c Rainer, Heinrich (1968). Urtiere, Protozoa; Wurzelfüẞler, Rhizopoda; Sonnentierchen, Heliozoa: Systematik und Taxonomie, Biologie, Verbreitung und Ökologie der Arten der Erde [Protozoa; Rhizopods; Heliozoa: systematics and taxonomy, biology, distribution and ecology of the species of the Earth]. Die Tierwelt Deutschlands und der angrenzenden Meeresteile [The animal world of Germany and the adjacent sea areas] (in German). Vol. 56. Jena: VEB Gustav Fischer Verlag. OCLC 5630582.

- ^ a b c Adl, Sina M.; Bass, David; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Agatha, Sabine; Berney, Cedric; Brown, Matthew W.; Burki, Fabien; Cárdenas, Paco; Čepička, Ivan; Chistyakova, Lyudmila; Del Campo, Javier; Dunthorn, Micah; Edvardsen, Bente; Eglit, Yana; Guillou, Laure; Hampl, Vladimír; Heiss, Aaron A.; Hoppenrath, Mona; James, Timothy Y.; Karnkowska, Anna; Karpov, Sergey; Kim, Eunsoo; Kolisko, Martin; Kudryavtsev, Alexander; Lahr, Daniel J.G.; Lara, Enrique; Le Gall, Line (26 September 2018). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/JEU.12691. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Gabaldón, Toni; Völcker, Eckhard; Torruella, Guifré (17 June 2022). "On the Biology, Diversity and Evolution of Nucleariid Amoebae (Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta)". Protist. 173 (4): 125895. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2022.125895. hdl:2117/369912. PMID 35841659.

- ^ a b Page, Frederick C. (1987). "The classification of 'naked' amoebae (Phylum Rhizopoda)". Archiv für Protistenkunde. 133 (3–4): 199–217. doi:10.1016/S0003-9365(87)80053-2.

- ^ a b c Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (1993). "Kingdom Protozoa and its 18 phyla". Microbiological Reviews. 57 (4): 953–994. doi:10.1128/mr.57.4.953-994.1993. PMC 372943. PMID 8302218.

- ^ a b c d Tedersoo, Leho; Sánchez-Ramírez, Santiago; Kõljalg, Urmas; Bahram, Mohammad; Döring, Markus; Schigel, Dmitry; May, Tom; Ryberg, Martin; Abarenkov, Kessy (2018). "High-level classification of the Fungi and a tool for evolutionary ecological analyses". Fungal Diversity. 90 (1): 135–159. doi:10.1007/s13225-018-0401-0. ISSN 1560-2745.

- ^ a b c Worley, Ann C.; Raper, Kenneth B.; Hohl, Marianne (1979). "Fonticula alba: a new cellular slime mold (Acrasiomycetes)". Mycologia. 71 (4): 746–760. doi:10.1080/00275514.1979.12021068.

- ^ a b Zettler, Linda A. Amaral; Nerad, Thomas A.; O'Kelly, Charles J.; Sogin, Mitchell L. (11 July 2005). "The nucleariid amoebae: more protists at the animal-fungal boundary". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 48 (3): 293–297. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2001.tb00317.x. PMID 11411837. S2CID 44548329.

- ^ a b López-Escardó, David; López-García, Purificación; Moreira, David; Ruiz-Trillo, Iñaki; Torruella, Guifré (2017). "Parvularia atlantis gen. et sp. nov., a Nucleariid Filose Amoeba (Holomycota, Opisthokonta)". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 65 (2): 170–179. doi:10.1111/jeu.12450. ISSN 1550-7408. PMC 5708529. PMID 28741861.

- ^ a b c d e Galindo, Luis Javier; Torruella, Guifré; Moreira, David; Eglit, Yana; Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Völcker, Eckhard; Clauẞ, Steffen; López-García, Purificación (7 October 2019). "Combined cultivation and single-cell approaches to the phylogenomics of nucleariid amoebae, close relatives of fungi". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. Biological Sciences. 374 (1786): 20190094. doi:10.1098/rstb.2019.0094. PMC 6792443. PMID 31587649.

- ^ Patterson DJ (May 1985). "On the Organization and Affinities of the Amoeba, Pompholyxophrys punicea Archer, Based on Ultrastructural Examination of Individual Cells from Wild Material 1". J. Protozool. 32 (2): 241–6. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1985.tb03044.x.

- ^ Yoshida M, Nakayama T, Inouye I (January 2009). "Nuclearia thermophila sp. nov. (Nucleariidae), a new nucleariid species isolated from Yunoko Lake in Nikko (Japan)". European Journal of Protistology. 45 (2): 147–155. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2008.09.004. PMID 19157810.

- ^ Dirren, Sebastian; Pitsch, Gianna; Silva, Marisa O.D.; Posch, Thomas (August 2017). "Grazing of Nuclearia thermophila and Nuclearia delicatula (Nucleariidae, Opisthokonta) on the toxic cyanobacterium Planktothrix rubescens" (PDF). European Journal of Protistology. 60: 87–101. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2017.05.009. PMID 28675820.

- ^ Steenkamp, Emma T.; Wright, Jane; Baldauf, Sandra L. (8 September 2005). "The Protistan Origins of Animals and Fungi". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (1): 93–106. doi:10.1093/molbev/msj011. PMID 16151185.

- ^ a b c Brown, Matthew W.; Spiegel, Frederick W.; Silberman, Jeffrey D. (2009-12-01). "Phylogeny of the "Forgotten" Cellular Slime Mold, Fonticula alba, Reveals a Key Evolutionary Branch within Opisthokonta". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 26 (12): 2699–2709. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp185. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 19692665.

- ^ Liu, Yu; Steenkamp, Emma T.; Brinkmann, Henner; Forget, Lisa; Philippe, Hervé; Lang, B. Franz (2009). "Phylogenomic analyses predict sistergroup relationship of nucleariids and Fungi and paraphyly of zygomycetes with significant support". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 9 (1): 272. Bibcode:2009BMCEE...9..272L. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-272. PMC 2789072. PMID 19939264.

- ^ a b c Galindo, Luis Javier; Torruella, Guifré; López-García, Purificación; Ciobanu, Maria; Gutiérrez-Preciado, Ana; Karpov, Sergey A; Moreira, David (2023). "Phylogenomics Supports the Monophyly of Aphelids and Fungi and Identifies New Molecular Synapomorphies". Systematic Biology. 72 (3): 505–515. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syac054. PMID 35900180.

- ^ Wijayawardene NN, Hyde KD, Al-Ani LK, Tedersoo L, Haelewaters D, Rajeshkumar KC, et al. (2020). "Outline of Fungi and fungus-like taxa" (PDF). Mycosphere. 11 (1): 1060–1456. doi:10.5943/mycosphere/11/1/8. ISSN 2077-7019.

- ^ Shalchian-Tabrizi, Kamran; Minge, Marianne A.; Espelund, Mari; Orr, Russell; Ruden, Torgeir; Jakobsen, Kjetill S.; Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (7 May 2008). "Multigene Phylogeny of Choanozoa and the Origin of Animals". PLOS ONE. 3 (5): e2098. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2098S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002098. PMC 2346548. PMID 18461162.

- ^ Penard, Eugène (1904). Les héliozoaires d'eau douce [The freshwater heliozoans] (in French). Genève: W. Kündig & fils. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.1407. OCLC 8236527. BHL page 1095193.

- ^ Cann, John P. (August 1986). "The feeding behavior and structure of Nuclearia delicatula". Journal of Protozoology. 33 (3): 392–396. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1986.tb05629.x.

- ^ a b c Patterson, D. J.; Simpson, A. G. B.; Rogerson, A. (2000). "Amoebae of uncertain affinities" (PDF). In Lee, John J.; Leedale, Gordon F.; Bradbury, Phyllis (eds.). The Illustrated Guide to the Protozoa: organisms traditionally referred to as protozoa, or newly discovered groups. Vol. II (2nd ed.). Society of Protozoologists. pp. 804–827.

- ^ Deasey, Mary C.; Olive, Lindsay S. (31 July 1981). "Role of Golgi apparatus in sorogenesis by the cellular slime mold Fonticula alba". Science. 213 (4507): 561–563. Bibcode:1981Sci...213..561D. doi:10.1126/science.213.4507.561. PMID 17794844.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Chao, Ema E. (July 2012). "Oxnerella micra sp. n. (Oxnerellidae fam. n.), a tiny naked centrohelid, and the diversity and evolution of Heliozoa". Protist. 163 (4): 574–601. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2011.12.005. PMID 22317961.

- ^ a b c d e f Mikrjukov, Kirill A. (1999). "Taxonomic revision of scale-bearing heliozoon-like amoebae (Pompholyxophryidae, Rotosphaerida)". Acta Protozoologica. 38 (2): 119–131.

- ^ Mikrjukov, Kirill A.; Mylnikov, Alexander P. (2001). "A study of the fine structure and the mitosis of a lamellicristate amoeba, Micronuclearia podoventralis gen. et sp. nov. (Nucleariidae, Rotosphaerida)". European Journal of Protistology. 37 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1078/0932-4739-00783.

- ^ Ruggiero, Michael A.; Gordon, Dennis P.; Orrell, Thomas M.; Bailly, Nicolas; Bourgoin, Thierry; Brusca, Richard C.; Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Guiry, Michael D.; Kirk, Paul M. (29 April 2015). "A higher level classification of all living organisms". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0119248. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019248R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119248. PMC 4418965. PMID 25923521.

- ^ Adl, Sina M.; Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Bass, David; Bowser, Samuel S.; Brown, Matthew W.; Burki, Fabien; Dunthorn, Micah; Hampl, Vladimir; Heiss, Aaron; Hoppenrath, Mona; Lara, Enrique; le Gall, Line; Lynn, Denis H.; McManus, Hilary; Mitchell, Edward A. D.; Mozley-Stanridge, Sharon E.; Parfrey, Laura W.; Pawlowski, Jan; Rueckert, Sonja; Shadwick, Laura; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Spiegel, Frederick W. (28 September 2012). "The Revised Classification of Eukaryotes". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 59 (2): 429–514. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x. PMC 3483872. PMID 23020233.

- ^ Takahashi, Yuki; Yoshida, Masaki; Inouye, Isao; Watanabe, Makoto M. (October 2016). "Fibrophrys columna gen. nov., sp. nov: a member of the family Amphifilidae". European Journal of Protistology. 56: 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2016.06.003. PMID 27468745.

- ^ Nicholls, Kenneth H. (17 September 2012). "New and little-known marine species of Pinaciophora, Rabdiaster and Thomseniophora gen. nov. (Rotosphaerida: Pompholyxophryidae)". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 93 (5): 1211–1229. doi:10.1017/S002531541200135X.