Paris under Louis-Philippe

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

| History of Paris |

|---|

|

| See also |

|

|

Paris during the reign of King Louis-Philippe (1830–1848) was the city described in the novels of Honoré de Balzac and Victor Hugo. Its population increased from 785,000 in 1831 to 1,053,000 in 1848, as the city grew to the north and west, while the poorest neighborhoods in the center became even more crowded.[1]

The heart of the city, around the Île de la Cité, was a maze of narrow, winding streets and crumbling buildings from earlier centuries; it was picturesque, but dark, crowded, unhealthy and dangerous. A cholera outbreak in 1832 killed 20,000 people. Claude-Philibert de Rambuteau, prefect of the Seine for fifteen years under Louis-Philippe, made tentative efforts to improve the center of the city: he paved the quays of the Seine with stone paths and planted trees along the river. He built a new street (now the Rue Rambuteau) to connect the Marais district with the markets and began construction of Les Halles, the famous central food market of Paris, finished by Napoleon III.[2]

Louis-Philippe lived in his old family residence, the Palais-Royal, until 1832, before moving to the Tuileries Palace. His chief contribution to the monuments of Paris was the completion in 1836 of the Place de la Concorde, which was further embellished on 25 October 1836 by the placement of the Luxor Obelisk. In the same year, at the other end of the Champs-Élysées, Louis-Philippe completed and dedicated the Arc de Triomphe, which had been begun by Napoleon I.[2]

The ashes of Napoleon were returned to Paris from Saint Helena in a solemn ceremony on 15 December 1840, and Louis-Philippe built an impressive tomb for them at the Invalides. He also placed the statue of Napoleon on top of the column in the Place Vendôme. In 1840, he completed a column in the Place de la Bastille dedicated to the July 1830 revolution which had brought him to power. He also sponsored the restoration of the Paris churches ruined during the French Revolution, a project carried out by the ardent architectural historian Eugène Viollet-le-Duc; the first church slated for restoration was the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Between 1837 and 1841, he built a new Hôtel de Ville with an interior salon decorated by Eugène Delacroix.[3]

The first railway stations in Paris (then called embarcadères) were built under Louis-Philippe. Each belonged to a different company, and they were not connected to each other; all were located outside the city center. The first, the Embarcadère Saint-Germain, was opened on 24 August 1837 on the Place de l'Europe. An early version of the Gare Saint-Lazare was started in 1842, and the first lines from Paris to Orléans and to Rouen were inaugurated on 1–2 May 1843.[4]

As the population of Paris grew, so did discontent in the working-class neighborhoods. There were riots in 1830, 1831, 1832, 1835, 1839, and 1840. The 1832 uprising, which followed the funeral of a fierce critic of Louis-Philippe, General Jean Maximilien Lamarque, was immortalized by Victor Hugo in his novel Les Misérables.[5]

The growing unrest finally exploded on 23 February 1848, when a large demonstration was broken up by the army. Barricades went up in the eastern working-class neighborhoods. The king reviewed his soldiers in front of the Tuileries Palace, but instead of cheering him, many shouted "Long Live Reform!" Discouraged, he abdicated and departed for exile in England.

Parisians

[edit]Population

[edit]The population of Paris grew rapidly during the reign of Louis-Philippe, from 785,866 recorded in the 1831 census, to 899,313 in 1836, and 936,261 in 1841. By 1846, it had grown to 1,053,897. Between 1831 and 1836, it grew by 14.4% within the city limits and by 36.7% in the villages around the city that became part of Paris in 1860.[6] The largest number of immigrants came from the twelve departments around Paris: 40% came from Picardy and the Nord department; 13% from Normandy; and 13% from Burgundy. A smaller number came from Brittany and Provence, and they had greater difficulties assimilating, since few of them spoke French. They tended to settle in the poorest neighborhoods between the Hôtel de Ville and Les Halles.[7]

Following earlier foreign immigration, a large wave of immigrants from Poland, including Frédéric Chopin, arrived after the failed Polish revolutions of 1830 and 1848.[7]

The most densely populated neighborhoods were in the center, where the poorest Parisians lived: Les Arcis, Les Marchés, Les Lombards and Montorgueil, where the population density reached between 1000 and 1500 persons per hectare. However, during the reign of Louis-Philippe, the middle class gradually moved away from the center toward the west and north of the Grands Boulevards. Between 1831 and 1836, the population of the 23 neighborhoods of the center dropped from 42.7% to 24.5% of the city's population, while the corresponding percentage for the outer neighborhoods grew from 27.3% to 58.7%. The population of the Left Bank remained steady at about 26% of the total.[8]

Social classes

[edit]The nobility, composed of several hundred families, continued to occupy their palatial town houses in the Faubourg Saint-Germain and held a prominent place in society, but exercised a much smaller role in the government and business of the city. Their place at the top of the social order was taken by the bankers, financiers and industrialists. The novelist Stendhal wrote: "The bankers are at the heart of the State. The bourgeoisie has taken the place of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, and the bankers are the nobility of the bourgeoisie."[9] The new leaders of Paris lived on the Right Bank, between the Palais Royal and the Madeleine to the north and west of the city. The Rothschild family and the bankers Jacques Laffitte and Casimir Perier lived on the Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin, north of the Place Vendôme, just outside the boulevards. The industrialist Benjamin Delessert lived on the Rue Montmartre. The upper middle class, those who paid more than 200 francs in direct taxes each year, numbered 15,000 families in a city of about a million inhabitants. The growing middle class also included owners of shops, merchants, artisans, notaries, doctors, lawyers, and government officials.

The reign of Louis-Philippe also saw a large increase in the number of working-class Parisians employed in the new factories and workshops created by the Industrial Revolution. A skilled worker earned three to five francs a day. An unskilled worker, such as those employed to use wheelbarrows to move earth during the construction of new streets, earned 40 sous, or two francs, a day.[10] The workers were mostly from the provinces and rented rooms in crowded hôtels garnis, or lodging houses. The population of the lodging houses grew from 23,000 to 50,000 between 1831 and 1846. They constituted the class most subject to the fluctuations of the business cycle and were the principal participants in the growing number of strikes and confrontations with the government.[8]

There was also a growing under-class in Paris of the unemployed or marginally employed. These included such occupations as the chiffonniers, who searched the trash at night for rags or old shoes that could be resold. Their number was estimated at 1800 in 1832.[11] There was also a very large number of orphans who lived by any means they could find in the streets of Paris. They are memorably described by Victor Hugo in Les Misérables.

Bohemians

[edit]

A new social type appeared in Paris in the 1840s; le bohème, or the "Bohemian". They were usually students or artists, and were generally described as joyous, careless about the future, somewhat lazy, boisterous, and scornful of middle-class standards. They wore a distinct costume, careless and flamboyant, to stand out from the crowd. The name was taken from the Romani people who originally immigrated to France from eastern Europe in the 15th century and were mistakenly believed to come specifically from Bohemia; they were numerous in Paris at the time. The character was first introduced into literature by Henri Murger in a series of stories called Scènes de la vie de Bohème (Scenes of Bohemian Life) published in Paris between 1845 and 1849, which in 1896 was made into the opera La Bohème by Puccini. The term spread from Paris to the rest of Europe, and came to be used for anyone who lived an artistic and unconventional life.[12]

Prostitution

[edit]Prostitution was common in Paris. Beginning in 1816, prostitutes were required to register with the police. Between 1816 and 1842, their numbers grew from 22,000 to 43,000. They were mostly young women from the French provinces who had come to Paris seeking regular work, but were unable to find it. At the beginning of the reign of Louis-Philippe, the prostitutes were usually found in the arcades of the Palais-Royal, but they were gradually moved by the police to the sidewalks of the Rue Saint-Denis, the Rue Saint-Honoré, the Rue Sainte-Anne, and the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Houses of prostitution, marked with red lanterns, were called maisons de tolerance or maisons closes. They were mostly found on the boulevards at the edges of the city, in Belleville, Ménilmontant, La Villette, La Chapelle, Grenelle, Montparnasse, and at the Place du Trone. They numbered 200 in 1850, just after the fall of Louis-Philippe.[13]

Governing

[edit]

Louis-Philippe had a very different style from previous monarchs; he did not move from his residence in the Palais-Royal to the Tuileries Palace until 1 October 1831. Except on ceremonial occasions, he dressed like a banker or industrialist rather than a king, with a blue coat, white waistcoat and top hat, and carried an umbrella. Formal court dress was no longer required at receptions. The royal guards were replaced by soldiers from the National Guard. His children attended the best Paris schools, rather than having tutors. He spent as little time as possible in Paris, preferring the royal residences at Fontainebleau, Versailles and the Château de Neuilly.[14]

As soon as he came to power, Louis-Philippe dismissed the old Prefect of the Seine, the Prefect of Police, the mayors of the arrondissements and their deputies, and the 24 members of the General Council of the Seine. On 29 July, he appointed a temporary municipal commission to run the city, under the authority of the Minister of the Interior. The new council was named on 17 September, and was made up mainly of bankers, industrialists, magistrates and senior government officials. The successive French governments since the Ancien Régime had feared the fury of the Parisians, and a repeat of the Reign of Terror. Parisians had not been allowed to elect a city government from 1800 until 1830; it was always directly under the rule of the national government. In 1831, Louis-Philippe organized the first municipal elections, but under conditions that ensured that the Parisians would not get out of control. Under a law of 30 April 1831, the Chamber of Deputies created a new General Council of the Seine, with 36 elected members from Paris, three per arrondissement, and eight from the neighboring arrondissements of Saint-Denis and Sceaux. Only Parisians who paid more than 200 francs a year in direct taxes were allowed to vote, although they numbered less than 15,000 in a city with a population of more than 800,000 persons. A few other selected categories of Parisians were also allowed to vote, including judges, notaries, members of the Institut de France, retired officers who received a pension of at least 1200 francs, and doctors who had practiced in Paris more than ten years. This added another 2000 to the number of eligible voters.[15]

Even with all these limitations on who could vote, Louis-Philippe's government feared that Paris could run out of control. The president and vice-president of the Council were named by the king from among the members of the Council. Only the Prefect of the Seine, appointed by the king, could bring business before the Council. Furthermore, a new parallel council was created, made up of the mayors and deputy mayors, which served to bypass the Municipal Council when needed. Despite all these efforts, the Council still demonstrated its independence on occasion. It forced the resignation of the first new Prefect of the Seine, Pierre-Marie Taillepied, Comte de Bondy, who rarely consulted the Council and disregarded their opinions. The new prefect, Claude-Philibert Barthelot de Rambuteau, learned the lesson and treated the Council with great courtesy, summoning them for meetings every week.[15]

Police

[edit]The other key figure in the government of Paris was the Prefect of Police. There were two of these during the reign of Louis-Philippe: Henri Gisquet (1831–1836) and Gabriel Delessert (1836–1848). The Prefect of Police oversaw the municipal police, the gendarmes in the city, and the firemen. He administered the prisons, hospitals, hospices, and public assistance; was responsible for public health and stopping industrial pollution; and was in charge of street lighting and street cleaning. He was also responsible for traffic circulation, making sure that building façades met city requirements, that unsafe buildings were demolished, and that the city's markets and bakeries were supplied with food and bread.[16]

On 16 August 1830, soon after Louis-Philippe assumed the throne, the royal police force of Paris, the gendarmerie royale, was abolished and replaced by the garde municipale de Paris, a force of 1,510 men originally composed of two battalions of infantry and two squadrons of cavalry. They were responsible for suppressing the numerous uprisings and riots between 1831 and 1848. Their numbers were doubled during that time, but their harsh tactics earned them the hatred of the insurgent Parisians; a substantial number of police were massacred by the crowds during the Revolution of 1848. The garde municipale was abolished in 1848 and replaced by the Garde Republicaine.[17]

The second corps responsible for maintaining order in the city was the Garde Nationale. At the end of the reign of Charles X, it had rebelled against the monarchy and helped overthrow the king. It was composed largely of the bourgeoisie of Paris, and members provided their own weapons. It had 60,000 members in Paris, though only 20,000 had income high enough to be eligible to vote. The Garde Nationale helped suppress the armed uprisings of 1832 and 1834, but from 1840 they were increasingly hostile to the government of Louis-Philippe. When the Revolution of 1848 broke out, they took the side of the insurgents and helped bring the regime to an end.[18]

Cholera epidemic

[edit]The first great crisis to strike Paris during the reign of Louis-Philippe was an epidemic of cholera in 1832. It was the first such epidemic in France, and the disease was little known or understood. It originated in Asia and spread through Russia, Poland, and Germany before reaching France. The first victim in Paris died on 19 February 1832. At first, the disease was not believed to be contagious, and the epidemic was not officially recognized until 22 March. As news of it spread, thousands of Parisians fled the city. 12,733 Parisians died in April, with a decrease in May and June, and a new surge in July, before the epidemic receded in September. Between March and September, it killed 18,402 Parisians, including Casimir Périer, the president of Louis-Philippe's Council of Ministers, who caught the disease after visiting cholera patients in hospital.

The disease was most fatal in the overcrowded neighborhoods of the center of Paris. As one measure of how crowded conditions were, there is record of one lodging house at 26 Rue Saint-Lazare where 492 persons lived in the same building, with less than one square meter of space per person. A rumor spread in the poor areas that the cholera had been spread deliberately to "assassinate the people". One of the victims of the epidemic was General Lamarque, a former general of the Napoleonic era, who died on June 1. He was seen as a defender of popular causes, and his funeral was the scene of a large anti-government demonstration, with some barricades going up in the streets. These events were immortalized in Victor Hugo's novel Les Misérables.[19]

The incumbent Prefect of the Seine was dismissed largely because of his inept handling of the epidemic, and the new Prefect, the Count of Rambuteau, declared his intention to bring "air and light" to the center of the city to prevent future epidemics. This was the beginning of the program to open up the center of the city, not fully realized until the time of Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann.

Monuments and architecture

[edit]

One of the great architectural projects of the reign of Louis-Philippe was the remaking of the Place de la Concorde. An equestrian statue of King Louis XV had originally been the centerpiece of the Place; during the Revolution the statue was pulled down and replaced by a statue of the Goddess of Liberty and the place was the site of the execution of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. Louis Philippe wanted to erase all the revolutionary associations of site. He selected Jacques Ignace Hittorff to design a new master plan, which was carried out in stages between 1833 and 1846. First the moat of the Tuileries Palace was filled in. Then Hittorff designed the two Fontaines de la Concorde, one commemorating river navigation and commerce, the other maritime navigation and commerce. On 25 October 1836, a new centerpiece was put in place: a stone obelisk from Luxor that weighed 250 tons and was brought to France on a specially built ship from Egypt. It was slowly hoisted into place in the presence of Louis-Philippe and a huge crowd.[20] At each angle of the square's extended octagon Hittorff placed a statue representing a French city: Bordeaux, Brest, Lille, Lyon, Marseille, Nantes, Rouen and Strasbourg. The face of the statue of Strasbourg, by the sculptor James Pradier, was said to be modeled after Juliette Drouet, the companion of Victor Hugo.[21]

In the same year, the Arc de Triomphe, begun in 1804 by Napoleon, was finally completed and dedicated. Many old soldiers from the Napoleonic armies were in the crowd, and they called out "Vive l'Empereur", but Louis-Philippe was unperturbed. The ashes of Napoleon were returned to Paris from Saint Helena in 1840, and were placed with great ceremony in a tomb designed by Louis Visconti beneath the church of Les Invalides.

Another Paris landmark, the July Column on the Place de la Bastille, was inaugurated on 28 July 1840, on the anniversary of the July Revolution, and dedicated to those killed during the uprising.

Several older monuments were put to new purposes: the Élysée Palace was purchased by the French state and became an official residence; and under later governments, it has served as the residence of the Presidents of the French Republic. The Basilica of Sainte-Geneviève, originally built as a church beginning in the 1750s, then made into a mausoleum for great Frenchmen during the French Revolution, then a church again during the Bourbon Restoration, once again became the Panthéon, dedicated to the glory of great Frenchmen.

Beginning of architectural restoration

[edit]

During the reign of Louis-Philippe a movement was launched to preserve and restore some of the earliest landmarks of Paris, many of which had been badly damaged during the Revolution. It was inspired in large part by Victor Hugo's hugely successful 1831 novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (Notre-Dame de Paris). The leading figure of the restoration movement was Prosper Mérimée, named by Louis-Philippe as the inspector General of Historic Monuments. In 1842, he compiled the first official list of classified historical monuments, now known as the Base Mérimée. In addition to saving architectural landmarks, he participated with his friend the novelist George Sand in the discovery of The Lady and the Unicorn tapestries at the Château de Boussac in the Limousin in central France; they are now the best-known possessions of the Cluny Museum in Paris. He also wrote the novella Carmen on which the opera of Bizet was based.

The first structure to be restored was the nave of the church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the oldest in the city. Work also began in 1843 on the cathedral of Notre-Dame, which had been stripped of the statues on its facade and of its spire. Much of the work was directed by the architect and historian Eugène Viollet-le-Duc who sometimes admitted that he was guided by his own scholarship of the "spirit" of medieval architecture, rather strict historical accuracy. The other major restorations projects were devoted to the medieval Sainte-Chapelle and the Hôtel de Ville, which dated from the 17th century. The old buildings that pressed up against the back of the Hôtel de Ville were cleared away, two new wings were added, the interiors were lavishly redecorated, and the ceilings and walls of the grands salons were painted with murals by Eugène Delacroix. Unfortunately, all the interiors were burned in 1871 by the Paris Commune.[20]

Rebuilding the city center and the boulevards

[edit]Rambuteau, during this fifteen years as Prefect of the Seine, made attempts to solve the blockage of traffic and the unhealthiness of the streets in the center, particularly after the cholera epidemic in the heart of the city. He opened the Rue d'Arcole and the Rue Soufflot and built what is now the Rue Rambuteau, thirteen meters wide, to connect the Le Marais district to the markets of Les Halles. He rebuilt what became known as the Pont Louis-Philippe from the Place de Gréve to the Île Saint-Louis and completely rebuilt the Pont des Saints-Pères. The île Louviers, just east of the Île Saint-Louis, used as a lumber yard, was attached to the Right Bank, and the Boulevard Morland replaced the narrow branch of the Seine that had separated the island from the city. The Pont d'Austerlitz, originally named for a Napoleonic military victory, the renamed the Pont du Jardin du Roi during the Bourbon Restoration, took back its Napoleonic name. The Quai de la Tournelle and the banks of the Seine at the Louvre and Quai des Grands-Augustins were walled with stone and planted with trees.[22]

At the beginning of the reign of Louis-Philippe, the old ramparts and bastions of Louis XIV were still visible in many places around the city, with a footpath running along the top. Rambuteau had them leveled in order to widen and straighten the Grands Boulevards. Only short sections of raised sidewalks on the Boulevard Saint-Martin and Boulevard de Bonne-Nouvelle showed how the ramparts formerly appeared (and they still show this today). Rambuteau also began rebuilding the old central market of Les Halles, but the new buildings, heavy and old fashioned, did not please the Parisians. The project was later stopped by Napoleon III when he was still prince-president of France (1848–1851). New glass and iron buildings were designed and built in their place by the architect Victor Baltard.

Sidewalks and public toilets

[edit]At the beginning of the reign of Louis-Philippe, Paris sidewalks in the center of the city, if they existed at all, were very narrow, rarely wide enough for two persons to walk side by side. Travelers described the adventure of trying to walk through the streets of the Île-de-la-Cité on a narrow, crowded sidewalk, the danger of stepping into the street in the path of carts, wagons and carriages, and the noise of the carriage wheels echoing on the walls of the street.[10] Sidewalks were common only in the new neighborhoods to the west and north and on the Grands Boulevards. In 1836, Rambuteau launched a project to build sidewalks in more neighborhoods and replace the old sidewalks made of lava stone with asphalt. By the end of the reign of Louis-Philippe, a majority of Paris streets were paved. Under Napoleon III, Haussmann completed the sidewalks by adding granite edges.[23]

Rambuteau also addressed the absence of public urinals, which gave the side streets and parks a particular and unpleasant smell. The first public urinals had been installed during the Bourbon Restoration, just before the Revolution of July 1830, but they were dismantled and used for barricades during the street fighting. In July 1839, Rambuteau authorized the construction of a new circular type of urinal, ten to twelve feet high, made of masonry with a pointed roof and posters displayed on the outside. The first ones were placed on the Boulevard Montmartre and the Boulevard des Italiens. By 1843, there were 468 urinals in place. They became known as vespasiennes after the Roman Emperor Vespasian, who was said to have installed public toilets in ancient Rome. They were all replaced during the Second Empire by a newer cast-iron design.[24]

Thiers Wall

[edit]

The city walls of Paris had been demolished during the reign of Louis XIV, and in 1814, the city was easily captured near the end of the War of the Sixth Coalition, since it had no fortifications. Debates began in Paris as early as 1820 about the necessity of building a new wall. In 1840, as the result of tensions between France, Britain and the German states, the discussion was renewed, and a plan was put forward by Adolphe Thiers, the President of the Council and the Minister of Foreign Affairs. The Thiers Wall, approved on 3 April 1841, was 34 kilometers long and composed of a belt of ramparts and trenches 140 meters wide. The highest rampart was ten meters high and three meters wide, and a road six meters wide ran the full length of the wall. It was forbidden to build any structure in a space 250 meters wide in front of the wall. The wall was reinforced at regular intervals with a series of bastions and 16 large forts around the city. In 1860, the route of the wall marked the official city limits of Paris, and it remains so, with a few changes, today. A number of the bastions still exist, and vestiges of the wall can still be seen at the Porte d'Arcueil (in the 14th arrondissement) and the point at which the Canal Saint-Denis passed through the wall. The Boulevard Périphérique around the city follows the route of the old Thiers wall.[25]

Social reforms and education

[edit]Rambuteau also made attempts to improve the social institutions of the city. He built a new prison, La Roquette, for criminals, while the mentally ill and sick were separated and left in the Bicêtre Hospital. Women prisoners were sent to the Enclos Saint-Lazare. Rambuteau began building the Lariboisière Hospital (in the 10th arrondissement), and he reorganized the Mont-de-Piété, a charitable organization which gave low-cost loans to the poor. In addition, he increased the number of savings banks for workers and middle-class Parisians. Primary education had previously been the responsibility of the Church, and many children remained illiterate. Under Louis-Philippe's minister of education, François Guizot, primary school was made obligatory as of 28 June 1833. A system of communal and mutual schools was created, as well as two higher primary schools: the Collège Chaptal (now Lycée Chaptal) and the Turgot School (1839). All of the primary schools, both Catholic and secular, were put under the authority of a central committee on education, with the Prefect as president.[26]

Water and fountains

[edit]The canals that brought drinking water to Paris, begun by Napoleon, were extended, and Rambuteau increased the number of borne-fontaines, small water fountains 50 centimeters high with a simple spout, from 146 in 1830 to 2,000 in 1848.[27] Despite the rapid growth of the city, no new sources of water were developed. The wealthiest Parisians had wells in their residences, usually in the basement. Most Parisians obtained their drinking water in a traditional way by visiting the city's fountains, sending servants to the fountains, or buying water from the water porters, mostly men from Auvergne and Piedmont, who carried large buckets balanced on a pole on their shoulders.

During the reign of Louis-Philippe, five new monumental fountains were erected in the center of the city: the two fountains designed by Jacques Ignace Hittorff in the Place de la Concorde; the Fontaine Molière on the Rue de Richelieu designed by Louis Visconti (who also designed the tomb of Napoleon); the Fontaine Louvois on the Square Louvois, designed by Visconti on the site of the old opera house; and the Fontaine Saint-Sulpice, also by Visconti, at the center of the Place Saint-Sulpice.[22]

-

The Fontaine des Fleuves, designed by Jacques Ignace Hittorff, Place de la Concorde (1840)

-

The Fontaine Molière, designed by Louis Visconti (1844)

-

The Fontaine Louvois, designed by Louis Visconti (1836–1839)

-

The Fontaine Saint-Sulpice, designed by Louis Visconti (1843–1848)

Railroad arrives

[edit]

The most important economic and social event of the reign of Louis-Philippe was the arrival in Paris of the railroad. The first successful passenger railway line in France had opened between Saint-Étienne and Lyon in 1831. The financiers, the Péreire brothers, built the first line from Paris to Saint-Germain-en-Laye between 1835 and 1837, largely in order to persuade the banking community and the Parisians that such a means of transport was feasible and profitable. The line between Paris and Versailles was approved on 9 July 1836; it was the site of the first railroad accident in France on 8 May 1842, in which at least 55 passengers were killed and between 100 and 200 injured,[28] The accident did not slow down the growth of the railroads: the Paris-Orléans line opened on 2 May 1843, and the line between Paris and Rouen was inaugurated the next day.[29]

The first train stations in Paris were called embarcadéres (a term borrowed from river navigation)), and their location was a source of great contention, since each railroad line was owned by a different company, and each went in a different direction. The first embarcadére was built by the Péreire brothers for the line Paris-Saint-Germain-en-Laye, at the Place de l'Europe; it opened on 26 August 1837. It became so successful that it was quickly replaced by a larger building on the Rue de Stockholm, and then an even larger structure, the beginning of the Gare Saint-Lazare, built between 1841 and 1843. It was the station for the trains to Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Versailles and Rouen.

The Péreire brothers argued that Gare Saint-Lazare should be the only railway station in Paris, but the owners of the other lines each insisted on having their own station. The first Gare d'Orléans, now known as the Gare d'Austerlitz, was opened on 2 May 1843 and was greatly expanded in 1848 and 1852. The first Gare Montparnasse opened on 10 September 1840 on the Avenue du Maine and was the terminus of the new Paris–Versailles line on the Left Bank of the Seine. It was quickly found to be too small and was rebuilt between 1848 and 1852 at the junction of the Rue de Rennes and Boulevard du Montparnasse, its present location.[30]

The banker James Mayer de Rothschild received the permission of the government to build the first railroad line from Paris to the Belgian border in 1845, with branch lines to Calais and Dunkerque. The first embarcadére of the new line opened on the Rue de Dunkerque in 1846. It was replaced by a much grander station, the Gare du Nord, in 1854. The first station of the line to eastern France, the Gare de l'Est, was begun in 1847, but not finished until 1852. Construction of a new station for the line to the south, from Paris to Montereau-Fault-Yonne began in 1847 and was finished in 1852. In 1855, it was replaced by a new station, the first Gare de Lyon, on the same site.[30]

Economy

[edit]Industry

[edit]The Industrial Revolution steadily changed the economy and the appearance of Paris, as new factories were built along the Seine and in the outer neighborhoods of the city. The textile industry was in decline, but the chemical industry was expanding around the edges of the city, at Javel, Grenelle, Passy, Clichy, Belleville and Pantin. It was joined by mills and factories that made steel, machines and tools, especially for the new railroad industry. Paris ranked third in France in metallurgy, after Saint-Étienne and the Nord department. Between 1830 and 1847, twenty percent of all the steam engines produced in France were made in Paris. Many of these were produced at the locomotive factory built by Jean-François Cail in 1844, first at Chaillot, then at Grenelle, which became one of the largest enterprises in Paris.

One example of the new factories in Paris was the cigarette and cigar factory of Philippon, between the rue de l'Université and the Quai d'Orsay. Napoleon's soldiers had brought the habit of smoking from Spain, and it had spread among all classes of Parisians. The government had a monopoly on the manufacture of tobacco products, and the government-owned factory opened in 1812. It employed 1,200 workers, a large number of them women, and also included a school and laboratory, run by the École Polytechnique, to develop new methods of tobacco production.[31]

Despite the surge of industrialization, most Parisian workers were employed in small workshops and enterprises. In 1847, there were 350,000 workers in Paris employed in 65,000 businesses. Only seven thousand businesses employed more than ten workers. For example, in 1848 there were 377 small workshops in Paris that made and sold umbrellas, employing a total of 1,442 workers.[32]

Banking and finance

[edit]

With the surge of industrialization, the importance of banking and finance in the Paris economy also grew. As Stendhal wrote at the time, the bankers were the new aristocracy of Paris. In 1837, Jacques Laffitte founded the first business bank in Paris, the Caisse Générale du Commerce et de l'Industrie. In 1842, Hippolyte Ganneron founded a rival commercial bank, the Comptoir Général du Commerce. The banks provided the funding for the most important economic event of the reign of Louis-Philippe: the arrival of the railroads. The brothers Émile and Issac Péreire, the grandchildren of an immigrant from Portugal, founded the first railway line to Paris.

James Mayer de Rothschild, the chief rival of the Péreire brothers, was the most famous banker of during the reign of Louis-Philippe. He gave loans to the royal government and played a key role in the construction of the French mining industry and railroad network. In 1838, he purchased the house of Charles Maurice de Talleyrand at 2 Rue Saint-Florentin on the Place de la Concorde for his Paris residence. He became a leading figure in Paris society and the arts; his personal chef was Marie-Antoine Carême, one of the most famous names in French cuisine.[33] He patronized many of the leading artists of the time, including Gioacchino Rossini, Frédéric Chopin, Honoré de Balzac, Eugène Delacroix, and Heinrich Heine. Chopin dedicated his Ballade No. 4 in F minor, Op. 52 (1843), and his Valse in C-sharp minor, Op. 64, N° 2 (1847), to Rothschild's daughter Charlotte. In 1848, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres painted his wife's portrait.

Boutiques and luxury goods

[edit]

The reign of Louis-Philippe became known as "the reign of the boutique". During this period, Paris continued to be the marketplace of luxury goods for the wealthiest customers in Europe, and the leader in fashion. The perfumer Pierre-François-Pascal Guerlain had opened his first shop on the Rue de Rivoli in 1828. In 1840, he opened a larger shop at 145 Rue de la Paix, which was also the first street in Paris to be lit with gaslight. The porcelain factory at Sèvres, which had long made table settings for the royal courts of Europe, began to make them for the bankers and industrialists of Paris.

The Passage des Panoramas and other covered shopping galleries were ancestors of the modern shopping center. Another new kind of store was the magasin de nouveautés, or novelty store. The "Grand Colbert" in the Galerie Colbert on the Rue Vivienne was decorated and organized like an oriental bazaar; it had large plate-glass windows and window displays, fixed prices and price tags, and sold a wide variety of products for women, from cashmere and lace to hosiery and hats. It was an ancestor of the first modern department stores, which appeared in Paris in the 1850s. Other novel marketing techniques were introduced in Paris at this time: the illuminated sign, and advertising goods in newspapers. The arrival of the railroad made it possible for people from the provinces to come to Paris simply to shop.[34]

Daily life

[edit]Transportation

[edit]The first means of public transport, the omnibus, had been introduced in Paris in January 1828, and it enjoyed great success. It used large horse-drawn coaches, was entered from the rear, and could carry between twelve and eighteen passengers. The fare was 25 centimes. The omnibuses operated between seven in the morning and seven in the evening in most location, but operated until midnight on the Grands Boulevards. In 1830, there were ten omnibus companies; by 1840, the number had increased to thirteen operating omnibuses on 23 different lines, though half of the passengers were carried by one company, Stanislas Baudry's Entreprise Générale des Omnibus de Paris (EGO).[35]

The other common means of transport was the fiacre, the taxicab of its day. It was a small box-like coach that carried as many as four passengers; it could be hired at designated stations around Paris. A single journey cost 30 sous, regardless of distance; or they could be hired at the rate of 45 sous for an hour. The drivers expected a tip, and, according to a guidebook of 1842, became extremely unpleasant if they did not receive one.[10]

Food and drink

[edit]The staples of the Parisian diet, unchanged since the 18th century, were bread, meat and wine. Upper-class Parisians began the day with coffee and bread, then they had their déjeuner (lunch) at mid-day, often at a café; they often started with oysters, followed by beefsteaks, vegetables, fruit, dessert and coffee. The meal was accompanied by wine, often diluted with water. They had their dinner at six or seven in the evening, with a larger number of dishes. They often went to the theater afterwards, then went to a café following the performance for coffee and drinks or a light supper.

For working-class Parisians, bread composed seven-eighths of their diet. They accompanied it with whatever fruit might be in season, some white cheese, and, in winter, some pieces of pork or bacon, along with stewed pears or roasted apples. They usually had some sort of soup each night, and on Sunday traditionally ate a stew called pot-au-feu. The meals were always accompanied by wine, usually with water added.[10]

The economic difficulties for ordinary Parisians during the reign of Louis-Philippe can be illustrated by their meat consumption; between 1772 and 1872, Parisians consistently ate about sixty kilograms of meat per year per person, but meat consumption between 1831 and 1850 fell to about fifty kilograms.[36]

Bathing

[edit]

Only a small number of Parisians had indoor plumbing or bathtubs; for most, water for washing had to be carried from a fountain or purchased from a water-bearer and stored in a container, and was used sparingly. Paris had a number of bath houses, including some, such as the Chinese Baths on the Boulevard des Italiens, which catered to upper-class customers.

For the working class, there was a row of floating baths along the Seine between the Pont d'Austerlitz and the Pont d'Iéna that operated during the summer. These were basins of river water surrounded by fences and usually by floating arcades of changing rooms. They were open day and night for an admission fee of four sous or twenty centimes. They had separate sections for men and women, and bathing costumes could be rented. They were often condemned by the church and in the press as an offense to public morality, but were always crowded with young working-class Parisians on hot summer days. Some of the floating baths were designed for wealthier patrons, some were used as schools to teach swimming, and some were reserved for women only; one was located in front of the Hôtel Lambert on the Quai d'Anjou.[37]

Press

[edit]

At the beginning of the reign of Louis-Philippe, the city's newspapers were expensive, had very small circulations, contained very little news, and were read mostly at cafés. That changed dramatically on 1 July 1836 with the debut of La Presse, the first inexpensive daily newspaper in Paris. It soon inspired many imitators. Between 1830 and 1848, the circulation of newspapers in Paris doubled; in 1848, there were 25 newspapers in the city with a total circulation of 150,000. Despite official censorship, they played an increasing role in French politics and in the events that culminated in the Revolution of 1848. The press also began to play a novel role in commerce: Paris stores and shops began to advertise their products in the newspapers.[38]

Illustrated newspapers, often with satirical cartoons, also became popular and influential. The journalist Charles Philipon started an illustrated weekly magazine called La Caricature in 1830. He used the new technique of lithography to reproduce cartoons and employed a young caricaturist from Marseille, Honoré Daumier. Balzac, a friend of Philipon, also contributed to the magazine, using a pseudonym. In 1832, encouraged by the success of the magazine, he began a more popular daily four-page illustrated satirical newspaper called Le Charivari with caricatures by Daumier. It began with social satire, but soon veered into politics, ridiculing, among other targets, the king. In 1832, Daumier published a caricature of Louis-Phillippe as Gargantua eating the wealth of the nation, and another of the king's face in the shape of a pear. Daumier was arrested and served six months in prison. Philipon also served six months in prison for "contempt of the king's person." By 1835, the newspaper staff had been taken to court seven times and convicted four times. La Caricature ceased publication and Charivari switched from political to social satire, but the ridicule of the regime by the press continued to undermine public support for Louis-Philippe.

Numerous revolutionary newspapers were published in Paris by exiled political activists, then smuggled into their own countries. From 1843 to 1845, Karl Marx lived in Paris as editor of two radical German newspapers: Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher and Vorwärts!. It was in a café at the Palais-Royal that he met his future collaborator, Friedrich Engels. He was expelled from France in 1845 at the request of the Prussian government and moved to Brussels.

Culture, arts and amusement

[edit]Museums

[edit]

On 8 November 1833, a new museum of coins and medals was opened inside the Hôtel des Monnaies, the 18th-century French mint on the Left Bank.

Interest in the Middle Ages increased greatly in Paris after the publication of Victor Hugo's Notre-Dame de Paris and the first restoration of the cathedral. Alexandre Du Sommerard was a former soldier in Napoleon's army who became a counselor at the Cour des Comptes. He assembled and classified a large collection of art objects from the Middle Ages and Renaissance and purchased the Hôtel de Cluny, which he made his residence and private gallery to display his collection. After Du Sommerard's death in 1843, the French state bought the building and his collection, and the Hôtel de Cluny and the Roman baths adjacent to it became the Museum of the Middle Ages.

Literature

[edit]Many of the greatest and most popular works of French literature were written and published in Paris during the reign of Louis-Philippe.

- Victor Hugo published four volumes of poetry, and in 1831 published Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame), which was quickly translated into English and other European languages. The great popularity of the novel launched a movement for the restoration of the cathedral and other medieval monuments in Paris. In 1841, Louis-Philippe made Hugo a peer of France, a ceremonial position with a seat in the upper house of the French parliament (the Chamber of Peers). Hugo spoke out against the death penalty and for freedom of speech. While living in his house on the Place Royale (now the Place des Vosges), he began working on his next novel, Les Misérables.

- François-René de Chateaubriand refused to swear allegiance to Louis-Philippe and instead secluded himself in his apartment at 120 Rue du Bac, where he wrote his most famous work, the Mémoires d'outre-tombe, which was not published until after his death. He died in Paris on 4 July 1848, during the French Revolution of 1848.

- After writing several novels, Honoré de Balzac in 1832 conceived the idea of a series of books that would paint a panoramic portrait of "all aspects of society," eventually called La Comédie Humaine. He declared to his sister, "I am about to become a genius." He published Eugénie Grandet, his first bestseller, in 1833, followed by Le Père Goriot in 1835, the two-volume Illusions perdues in 1843, Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes and Le Cousin Pons in 1847 and La Cousine Bette 1848. In each of the novels, Paris is the setting and a major participant.

- The highly prolific Alexandre Dumas, père, published The Three Musketeers in 1844; Twenty Years After and La Reine Margot in 1845; The Count of Monte Cristo in 1845–1846; La Dame de Monsoreau in 1846; The Vicomte de Bragelonne in 1847; The Vicomte de Bragelonne in 1847; and many more novels in addition to many theatrical versions of his novels for the Paris stage.

- Stendhal published his first major novel, Le Rouge et le Noir, in 1830, and his second, La Chartreuse de Parme, in 1839.

Other major Paris writers of the July Monarchy included George Sand, Alfred de Musset, and Alphonse de Lamartine. The poet Charles Baudelaire, born in Paris, published his first works, essays of art criticism.

- Paris authors active during the reign of Louis-Philippe

-

François-René de Chateaubriand (1820s)

-

Alexandre Dumas, père (1832)

-

Victor Hugo and his son François-Victor (1836)

-

George Sand by Eugène Delacroix (1837)

-

Stendhal (1840)

-

Honoré de Balzac (1843)

Painting

[edit]The Paris Salon, held every year at the Louvre, continued to be the most important event in the French art world, establishing both prices and reputations of artists. It was dominated for most of the reign of Louis-Philippe by the romantic painters. The most prominent figure in painting was Eugène Delacroix, whose romantic paintings portrayed historical, patriotic and religious subjects. His most famous painting of the period, Liberty Leading the People (La Liberté guidant le peuple), an allegory of the 1830 revolution, was purchased by the French state, but was considered to be too inflammatory to be shown in public until 1848. Other prominent artists whose work appeared in the Paris Salon included Théodore Chassériau and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who had been a prominent figure in French painting since the reign of Napoleon I.

A new generation of artists made their appearance in the 1840s, led by Gustave Courbet, who exhibited his Self-Portrait with a Black Dog at the Paris Salon in 1844. His arrival as the leader of the realist movement did not come until after the 1848 Revolution.

- Prominent works of art from the reign of Louis-Philippe

-

Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix (1830)

-

Portrait of Louis Francois Bertin, by Dominique Ingres (1832 Salon)

-

The Toilette of Esther by Théodore Chassériau (1841 Salon)

-

The Two Sisters by Théodore Chassériau (1843 salon)

-

Self-Portrait with a Black Dog by Gustave Courbet (1844 Salon)

-

Christ on the Cross by Eugène Delacroix (1846 Salon)

Music

[edit]

Paris was the home of some of the world's most renowned musicians and composers during the July Monarchy. The most famous was Frédéric Chopin, who arrived in Paris from Poland in September 1831 at the age of twenty-one and never returned to his homeland after the Polish uprising against Russian rule in October 1831 was crushed. Chopin gave his first concert in Paris at the Salle Pleyel on 26 February 1832 and remained in the city for most of the next seventeen years, until his death in October 1849. He gave just 30 public performances during those years, preferring to give recitals in private salons instead. He earned his living mainly from commissions given by wealthy patrons, including the wife of James Mayer de Rothschild, the publication of his compositions, and from private piano lessons. Chopin lived at different times at 38 Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin and at 5 Rue Tronchet. He had a ten-year relationship with the writer George Sand between 1837 and 1847. In 1842, they moved together to the Square d'Orléans, at 80 Rue Taitbout, where the relationship ended.

Franz Liszt also lived in Paris during this period, composing music for the piano and giving concerts and music lessons. He lived at the Hôtel de France on the Rue La Fayette, not far from Chopin. The two men were friends, but Chopin did not appreciate the manner in which Liszt played variations on his music. The violinist Niccolò Paganini was a frequent visitor and performer in Paris. In 1836, he made an unfortunate investment in a Paris casino and went bankrupt. He was forced to sell his collection of violins to pay his debts.

The French composer Hector Berlioz had come to Paris from Grenoble in 1821 to study medicine, which he abandoned for music in 1824, attending the Paris Conservatory in 1826; he won the Prix de Rome for his compositions in 1830. He was working on his most famous work, the Symphonie Fantastique, at the time of the July 1830 revolution. It had its premiere on 4 December 1830.

Charles Gounod, born in Paris in 1818, was studying composition during the reign of Louis-Philippe, but had not yet written the opera Faust and his other best known works.

Photography

[edit]

Paris was the birthplace of modern photography. A process for capturing images on plates coated with light-sensitive chemicals had been discovered by Nicéphore Niépce in 1826 or 1827 in rural France. After this death in 1833, the process was refined by the Paris artist and entrepreneur Louis Daguerre, who had invented the Paris Diorama. His new method of photography, called the daguerrotype, was publicly announced to a joint meeting of the French Academy of Sciences and the Academy of Fine Arts in Paris on 19 August 1839. Daguerre gave the rights to the invention to the French nation, which offered them for free to any user in the world. In exchange, Daguerre received a pension from the French state. The daguerrotype became the most common method of photography during the 1840s and 1850s.

Theater and the Boulevard du Crime

[edit]

Parisians of all classes frequented the theater during the July Monarchy, lining up to see operas, dramas, comedies, melodramas, vaudeville and farce. Tickets ranged in price from ten francs for the best seats at the Italian Opera to 30 sous for a seat in the "paradis" the highest balcony, in one of the popular melodrama or variety theaters. These were the most important venues for theater in Paris in the 1830s and 1840s:

- Italian opera was performed under the auspices of the Théâtre-Italien at the Théâtre de la Renaissance on the Rue Méhul and Rue Neuve des Petits-Champs. It had two thousand seats, and all the singers and musicians were Italian.

- French opera was performed under the auspices of the Académie Royale de Musique on the Rue Le Pelletier, near the Théâtre-Italien.

- The Opéra-Comique performed at the Salle Favart, located on what is now called the Place Boïeldieu, and presented lighter operatic works.

- The Comédie Française performed at the Salle Richelieu on the Rue Richelieu. Its most famous dramatic star during the reign of Louis-Philippe was Mademoiselle Rachel (see below).

- The Odéon theater presented classical drama and comedy in competition with the Comédie Française. In the 1840s, its most famous star was Mademoiselle Georges who had been the leading actress of Paris theater during the First Empire and the Bourbon Restoration.

- The Théâtre du Gymnase on the Boulevard Bonne Nouvelle specialized in farce. Its most famous actor was Bouffé, considered the greatest comic actor of the period.

- The Théâtre du Vaudeville stood on the Place de la Bourse, facing the stock exchange, and was known for light comedy.

- The Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin, located on the Boulevard Saint-Martin, was known for melodrama and burlesque; its most famous star in the 1830s and 1840s was Frédérick Lemaître.

- The Théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique on the Boulevard Saint-Martin specialized in melodrama and vaudeville.

In addition to these stages, there was a separate group of five theaters, mostly for working class audiences, together on the Boulevard du Temple: the Cirque Olympique, the Folies-Dramatiques, the Théâtre de la Gaîté, the Théâtre des Funambules, and the Théâtre Saqui. They were best known for melodramas, giving that section of the street the nickname the Boulevard du Crime. The most famous theater of that group was the Funambules, known for its performances of the Pierrot mime Jean-Gaspard Deburau, who performed there from 1819 until 1846. He and his cultural milieu were memorably portrayed in the 1945 film by Marcel Carné, Les Enfants du Paradis (The Children of the Paradise).

The most famous female dramatic star of the Paris theater was Rachel Félix, better known as "Mademoiselle Rachel", a German actress who had come to the Comédie Française in Paris in 1830, and became celebrated for her dramatic roles in works of Jean Racine, Voltaire, and Pierre Corneille, particularly as Phèdre in Racine's play of the same name. The most famous male actor was Frédérick Lemaître, who gained fame by transforming a serious dramatic role, that of Robert Macaire, into a burlesque role. During the reign of Louis-Philippe, he starred in Victor Hugo's play Ruy Blas, and in the Balzac's play Vautrin. The latter play was promptly banned by royal censors, because his wig closely resembled that of Louis-Philippe.

Restaurants, cafes

[edit]

At the beginning of the reign of Louis-Philippe, the most celebrated restaurants were found in the arcades of the Palais-Royal, but by 1845, the Grands Boulevards, where the theaters were located, had become the main restaurant district. The most famous and expensive restaurants in the city were lined up along the Boulevard des Italiens: the Café Anglais at no. 13; the Café Riche at no. 16; the Maison dorée at no. 20; and the Café de Paris at no. 22. It was also the home of the Café Tortoni, known for its Italian ice creams and pastries. The Café Anglais was a frequent meeting place of the characters in Balzac's series of novels, La Comédie humaine.[39]

Guinguettes

[edit]Guinguettes created popular diversions for all classes of Parisians, especially on Sundays. They were taverns or cabarets mostly located just outside the city limits, where taxes on wine and spirits were lower; the greatest concentrations were in Montmartre, Belleville, Montrouge, and just outside the city customs tollhouses of Barrière d’Enfer, Maine, Montparnasse, Courtille, Trois Couronnes, Ménilmontant, Les Amandiers, and Vaugirard. They usually had musicians and dancing on Sundays, and Parisians often brought their whole families. There were 367 in 1830, of which 138 were in the city itself and 229 in the suburbs. In 1834, there were 1,496, of which 235 were in Paris and 261 outside the city limits.[40]

Amusement parks and pleasure gardens

[edit]

Amusement parks had been very popular during the Bourbon Restoration, but went into a decline during the reign of Louis-Philippe. They were summer gardens that offered food, drinks, music, dancing, acrobats, fireworks and other entertainments for an entry fee. They went into a decline as real estate prices rose and the valuable land was sold for building lots. The best known, the Nouveau Tivoli, at 88 Rue de Clichy, closed in 1842. The Jardin Turc on the Rue du Temple, a popular café and summer garden, continued until the early 20th century.

Panoramas and dioramas

[edit]A panorama was a very large realistic painting of a city or natural wonder, displayed in a circular building so that viewers, on a platform in the center, felt they were seeing real thing. The first panoramas had been introduced by the American engineer and entrepreneur Robert Fulton in the Passage des Panoramas on the Rue Montmartre in 1799. In 1831, the French inventor Jacques Daguerre invented the diorama, a display of two similar paintings lit by a moving lamp in such a way as to create the illusion of three dimensions. The building in which the diorama was located burned in 1839, and Daguerre turned his attention to developing the new technology of photography. A new theater for panoramas was built in 1839 by the architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff at the Carré Marigny on the Champs-Élysées to display Jean-Charles Langlois's monumental historical painting, The Burning of Moscow in 1812. The building, still standing, is now a theater located next to the Grand Palais.[41]

Fashion

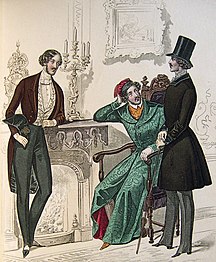

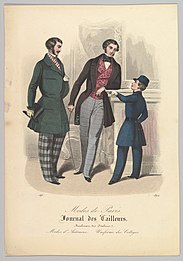

[edit]-

Paris dandies in 1831

-

On the Boulevard des Italiens (1833)

-

A fashion plate from the magazine Le Follet in 1839

-

Women on the terrace of the Café Tortoni (1847)

-

A fashion plate from the Journal des Tailleurs (1848)

Riots and revolutionaries

[edit]Despite his popularity with many Parisians at the beginning of his reign, Louis-Philippe almost immediately faced fierce opposition from those who wanted to replace the monarchy with a republic and press for radical social reforms; opposition was strongest among students, the working class and members of the new socialist movement. The first riot took place in December 1830, after the trial of the ministers of King Charles X; the crowd was furious that they were given life sentences instead of the death penalty. More riots took place in 1831 to protest a memorial service held at the church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois for the Duke of Berry, a prominent monarchist who had been assassinated on 14 February 1820 during the reign of King Louis XVIII. The interior of the church was pillaged, and the next day, the rioters attacked the church of Notre-Dame de Bonne-Nouvelle and the palace of the archbishop of Paris, next to the cathedral of Notre-Dame. The archbishop's residence was badly damaged and ultimately demolished.[42]

On 4 June 1832, the funeral procession of General Lamarque, an anti-monarchist army officer- popular with the students- who had died of cholera, was turned into a massive demonstration against the government; the protesters chanted "Long live the Republic!" and "Down with the Bourbons!". About 4000 students, workers and their supporters put up barricades in the narrow streets of the quarters of Les Lombards, Arcis, Sainte-Avoye and the Hôtel de Ville. They took control of the area of the city between Bastille and Les Halles, but there was little public support outside these neighborhoods. Despite fierce resistance from the students and workers, the rebellious area was gradually reduced by the army to the streets around cloister of Saint-Merri and crushed on 6 June. The state of emergency lasted until 29 June. 5000 persons were arrested, but only 82 were sentenced; seven were sentenced to death, with the sentences finally reduced to deportation. This event became a dramatic episode in Victor Hugo's novel Les Misérables. There were more demonstrations the following year, with the red flag raised on the Pont d'Austerlitz, more barricades raised in the Saint-Merri neighborhood and two days of fighting between government forces and revolutionaries. There were more riots and barricades in the same neighborhood in the spring of 1834; soldiers attacked a building from which they said shots had been fired and killed many of the demonstrators inside.[42]

The most dramatic attack on the government took place on 28 July 1835, the anniversary of the July Revolution of 1830. Louis-Philippe and his generals conducted a grand review of the army and National Guard lined up along the Grand Boulevards. At one o'clock in the afternoon, as Louis-Philippe and his entourage were passing the Café Turc on the Boulevard du Temple, an "infernal machine" of multiple gun barrels was fired from a window. Maréchal Mortier, duc de Trévise, riding with the king, was killed, and six generals, two colonels, nine officers and 21 spectators were wounded, some mortally. The king was grazed by a projectile, but gave the order to continue the parade. The organizer of the attack, Giuseppe Marco Fieschi, and his two accomplices were arrested and later guillotined.[42] These were not the last attacks on the Louis-Philippe: there was another attempt to shoot him in 1836, two in 1840, and two more in 1846, including one shooting attempt by a gunman while he was greeting the crowd in the Tuileries gardens from the balcony of the palace.

An attempted coup d'état took place in May 1839 in the center of the city, led by the radical republican Armand Barbés and the socialist Auguste Blanqui. On the afternoon of 12 May, about a thousand revolutionaries took up weapons and set out to seize the prefecture of police, the Châtelet, the Palais de Justice, and the Hôtel de Ville. They failed to capture the prefecture of police, and by the end of the afternoon, the regular army, municipal police and national guard had arrested most of the revolutionaries. The leaders were imprisoned until the end of the regime.[43]

Paris under Louis-Philippe also became a magnet for revolutionaries from other countries. Karl Marx moved to Paris in October 1843, and lived at 23 Rue Vaneau, where his daughter Jenny was born, and later at no. 38 on the same street. He became the editor of radical leftist German newspapers Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher and Vorwärts!. The famous Russian anarchist and revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin was also an editor of the Jahrbücher. On 28 August 1844, Marx met for the first time his future collaborator Friedrich Engels at the Café de la Régence at the Palais-Royal, a café renowned for the international chess masters who regularly played there. At the request of Frederick William IV, King of Prussia, Marx was expelled from France in April 1845. He then moved to Brussels.

Revolution of 1848

[edit]

The workers of Paris, especially those who had come from the provinces, were also increasingly dissatisfied with the government of Louis-Philippe. They complained of rising prices, low wages, and unemployment, and began to organize and go on strike. The workers on the new sewers were the first to strike, on 4 August 1832, followed by carpenters, then those working in wallpaper and garment factories. A period of economic growth calmed the unrest for a time but, in 1846 and 1847, a new economic crisis hit France in the form of a shortage of credit and money for investment caused by excessive speculation in the new railroads. Unemployment and the number of strikes increased, and confidence in the government's promises of prosperity fell.

The dominant issue that brought many Parisians into conflict with the government was the right to vote, which was limited only to the wealthiest citizens. Only a third of the members of the National Guard, the main defense force of the regime in Paris, had the right to vote. The conservative government, with Louis-Philippe's support, refused to broaden the number of voters. In the elections for the Chamber of Deputies in July 1842, conservatives and monarchists retained their majority, but in Paris, ten of the twelve new members belonged to the opposition, two of them republicans. In the elections of 1846, more than 9000 votes went to opposition candidates out of 14,000 cast. Increasingly, the Parisians were more critical of Louis-Philippe's government than the rest of the country.[44]

On 9 July 1847, the members of the opposition launched a new tactic to demand change in the electoral system: they held a large banquet in the park of the Château Rouge (now in the Quartier du Château Rouge) on the Rue de Clignancourt. The banquet was attended by 1200 persons, including 86 deputies. After this event, other opposition banquets were held in each of the arrondissements, and in cities around the country. One banquet was followed by a march of two to three thousand students under rain from the Madeleine and the Place de la Concorde. The government, under François Guizot, the Minister of the Interior, banned any further banquets and similar demonstrations and called on the National Guard to enforce the order. The National Guard, sympathetic to the opposition, refused to move, and instead chanted "Long live reform!" and "Down with Guizot!"

In the evening of 23 February 1848, a large crowd supporting the opposition gathered at the corner of the Rue Neuve des Capucines (since 1861, the Rue des Capucines) and Boulevard des Capucines in front of the now demolished Hôtel de Wagram, which housed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. At ten o'clock, at the sound of a gunshot, the battalion of soldiers guarding the building opened fire, killing 52 persons. At the news of the shooting, the leaders of the opposition called for an immediate uprising. On 24 February 1500 barricades went up all over Paris, many of them manned by soldiers of the National Guard. The commander of the regular army in Paris, Marshal Bugeaud, refused to give the order to open fire on the barricades. As a result, and on the same day, Louis-Philippe abdicated in favor of his nine-year-old grandson, Prince Philippe, Count of Paris. Simultaneously, a large crowd had invaded the Chamber of Deputies and called for a provisional government. A republican, Louis-Antoine Garnier-Pagès, was named the new mayor of Paris. On 25 February 1848, the poet Alphonse de Lamartine proclaimed the Second Republic and urged the crowd to keep the tricolor, rather than adopting the red flag as the national symbol. Another crowd invaded the Tuileries Palace, seized the royal throne, carried it to Place de la Bastille, and burned it at the foot of July Column. Louis-Philippe (in disguise as "Mr. Smith") and his family left the palace on foot through the garden of the Tuileries and reached the Place de la Concorde. There, they climbed into two carriages, and, with Louis-Philippe driving one carriage with three of his sons, fled Paris and took refuge in Dreux. On 2 March, the ex-king embarked at Le Havre for England, where he lived in exile with his family until his death on 26 August 1850.[45]

Chronology

[edit]

- 1830

- 25 February – Pandemonium in the audience at the Théâtre Français between the supporters of the classical style and those of the new romantic style during the first performance of Victor Hugo's romantic drama Hernani.

- 16 March – 220 deputies in the Chamber of Deputies send a message to King Charles X criticizing his governance.

- July – The first vespasiennes, or public urinals, also serving as advertising kiosks, appear on Paris boulevards.

- 25 July – Charles X issues the last of a series of ordinances (the July Ordinances) that dissolved the Chamber of Deputies, changed election laws and suppressed press freedom.

- 27–29 July – The July Revolution, or the Trois glorieuses, "three glorious" days of street battles between the army and opponents of the government. The insurgents install a provisional government in the Hôtel de Ville. Charles X leaves Saint-Cloud, his summer residence.

- 31 July – The Duke of Orléans, Louis-Philippe, comes to the balcony of the Hôtel de Ville and is presented to the crowd by the Marquis de Lafayette

- 9 August – Louis-Philippe is sworn as King of the French (Roi des Français).

- 1831

- Population – 785,000[46]

- 27 July – First stone laid of the July Column at the center of Place de la Bastille to honor those killed during the 1830 revolution.

- 31 October – Louis Philippe moves from the Palais-Royal to the Tuileries Palace.

- Victor Hugo's novel Hunchback of Notre-Dame is published, reviving interest in medieval Paris.

- 1832

- 19 February. First deaths from a cholera epidemic. Between 29 March and 1 October, the disease kills 18,500 persons.[47]

- Femme Libre, a feminist pamphlet, published in Paris.

- The illustrated Le Charivari, a satirical newspaper. begins publication.

- 1833

- Founding of the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul.

- 1834

- 30 October – The Pont du Carrousel is inaugurated.

- 1835

- 28 July – Assassination attempt on Louis-Philippe by Giuseppe Marco Fieschi, using an "infernal machine" of twenty gun barrels firing at once, as the king rides on the Boulevard du Temple during a commemoration of his accession to the throne in July 1830. The king and his sons are unharmed, but eighteen persons are killed, among them Édouard Mortier, a former Napoleonic general and Marshal of France.

- 1836

A huge crowd watched as the Luxor Obelisk was hoisted into place on the Place de la Concorde on 25 October 1836. - Founding of two popular inexpensive newspapers, La Presse and Le Siècle.

- 29 July – The Arc de Triomphe is dedicated.

- 25 October – Dedication of the Obelisk of Luxor on the Place de la Concorde.

- 1837

- 26 August – The first railroad line opens between the Rue de Londres and Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The trip takes half an hour.

- 1838

- Louis Daguerre takes the first modern photograph, called a daguerreotype, that shows a human figure, a man on the Boulevard du Temple having his shoes shined.

- The Bibliothèque Polonaise de Paris (Polish Library) is founded.

- 1839

- 7 January – Louis Daguerre presents his pioneer work on photography at the French Academy of Sciences. The academy grants him a pension and publishes the technology for free use by anyone in the world.

- 12–13 May – Followers of Louis Blanqui begin armed uprising in attempt to overthrow government, but are quickly arrested by the army and National Guard.[48]

- 2 August – Opening of a railway line along the Seine between Paris and Versailles.

- 1840

The ceremony for the return of Napoleon's ashes (15 December 1840) - 16 May – Opening of the new hall of the Opéra-Comique on the Place Favart.

- 14 June – During a review of the National Guard by Louis-Philippe at the Place du Carrousel, the soldiers shout slogans demanding reform.

- 28 July – Dedication of the July Column on the Place de la Bastille to honor those killed during the Revolution of 1830.

- 15 December – Napoleon's ashes are placed in the crypt of the church of Les Invalides.

- 24 December – The custom of the Christmas tree is introduced to Paris by Princess Hélène de Mecklembourg-Schwerin, wife of the Duke of Orléans, Louis-Philippe's eldest son.[48]

- 1841 – Population: 935,000[46]

- 27 February – The first artesian wells, 560 meters deep, go into service at Grenelle to provide drinking water.

- 1842

- The first French cigarettes are manufactured at Gros-Caillou, in the 7th arrondissement.

- 8 May – The first major railroad accident in France, on the Paris-Versailles line at Meudon, kills 57 persons and injures 30.[49]

- 1843

- 4 March – The newspaper L'Illustration, modeled on The Illustrated London News, begins publication.

- 2 May – The opening of a railroad line from Paris to Orléans, followed the next day by the opening of the line from Paris to Rouen.

- 7 July – The opening of the Quai Henry-IV, created by attaching the Île Louviers to the Right Bank.

- 20 October – First experiment with electric street lighting on the Place de la Concorde.

- 1844

- 16 March – Opening of the Cluny Museum, dedicated to the history and the arts of the medieval epoch in Europe (and also the Middle East and Maghreb).

- 14 November – The first crèche, or day care center, is opened at Chaillot.

- 1845

- A ring of new fortifications around the city (the Thiers wall), begun in 1841, is completed.

- 27 April – The first electric telegraph line tested between Paris and Rouen.

- 29 November – The first stone laid of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the Quai d'Orsay.

- 1846

- Population: 1,053,000[46]

- 7 January – Completion of the first Gare du Nord railway station. Train service to the north of France begins 14 June.

- 30 September – A riot breaks out in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine over the high cost of bread.

- 1847

- 19 February – Alexandre Dumas opens his new Théâtre Historique, located in the Boulevard du Temple, with the premiere of his La Reine Margot.

- 28 June – The city government decrees installation of new street numbers in white numbers on enameled blue porcelain plaques. These numbers remain until 1939.

- 9 July – Opponents of the government hold the first of a series of large banquets, the Campagne des banquets, to defy the law forbidding political demonstrations.[49]

- 1848

- February 24 – The beginning of the 1848 French Revolution (22–24 February).

- 22 February – The government bans banquets of the political opposition.

- 23 February – Crowds demonstrate against Louis-Philippe's chief minister, François Guizot. That evening, soldiers fire on a crowd outside Guizot's residence on the Boulevard des Capucines, killing 52.[50]

- 24 February – Barricades appear in many neighborhoods. The government resigns, Louis-Philippe and his family flee into exile in England, and the Second Republic is proclaimed at the Hôtel de Ville.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes and citations

[edit]- ^ Héron de Villefosse 1959, p. 323.

- ^ a b Héron de Villefosse 1959, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Héron de Villefosse 1959, pp. 325–327.

- ^ Héron de Villefosse 1959, pp. 325–331.

- ^ Manéglier, Hervé, Paris impérial, p. 19

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 282.

- ^ a b Fierro 1996, pp. 299–300.

- ^ a b Fierro 1996, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 435.

- ^ a b c d Hervé 1842.

- ^ Fierro, Alfred, Histoire et Dictionnaire de Paris, (1996), article on Chiffonniers, page 771

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 717.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 1120.

- ^ Sarmant 2012, pp. 166–169.

- ^ a b Fierro 1996, p. 326.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 327.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 895.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 898.

- ^ Fierro 1996, pp. 168–169.

- ^ a b Héron de Villefosse 1959, p. 325.

- ^ *Beatrice de Andia (editor), Paris et ses Fontaines, de la Renaissance a nos jours, Collection Paris et son Patrimoine, Paris, 1995

- ^ a b Héron de Villefosse 1959, p. 324.

- ^ Fierro 1996, pp. 1183–1184.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 1177.

- ^ Fierro 1996, pp. 848–849.

- ^ Héron de Villefosse 1959, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 720.

- ^ Mercier, Pierre (1993). "L'opinion publique après le déraillement de Meudon en 1842". Paris et Ile-de-France – Mémoires (Tome 44) (in French). Fédération des sociétés historiques et archéologiques de Paris et Ile-de-France.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 765.

- ^ a b Fierro 1996, pp. 900–901.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 1165.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 470.

- ^ Crème du Carême

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 464.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 1052.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 1191.

- ^ Fierro 1996, pp. 698–699.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 1106.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 1138.

- ^ Fierro 1996, pp. 918–919.

- ^ Fierro 1996, pp. 1044–1045.

- ^ a b c Héron de Villefosse 1959, p. 328.

- ^ Héron de Villefosse 1959, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 176.

- ^ Héron de Villefosse 1959, pp. 333–334.

- ^ a b c Combeau 2013, p. 61.

- ^ Fierro 1996, p. 617.

- ^ a b Fierro 1996, p. 618.

- ^ a b Fierro 1996, p. 619.

- ^ (in French) Révolution française de 1848, Encyclopédie Larousse.

Bibliography

[edit]- Combeau, Yvan (2013). Histoire de Paris. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-060852-3.

- Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-07862-4.

- Héron de Villefosse, René (1959). Histoire de Paris. Bernard Grasset.

- Hervé, F. (1842). How to enjoy Paris in 1842. London: G. Briggs.

- Jarrassé, Dominique (2007). Grammaire des Jardins Parisiens. Paris: Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-476-6.

- Le Roux, Thomas (2013). Les Paris de l'industrie 1750–1920. CREASPHIS Editions. ISBN 978-2-35428-079-6.

- Sarmant, Thierry (2012). Histoire de Paris: Politique, urbanisme, civilisation. Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-2-755-803303.

- Trouilleux, Rodolphe (2010). Le Palais-Royal- Un demi-siècle de folies 1780–1830. Bernard Giovanangeli.

- Du Camp, Maxime (1870). Paris: ses organes, ses fonctions, et sa vie jusqu'en 1870. Monaco: Rondeau. ISBN 2-910305-02-3.

- Dictionnaire Historique de Paris. Le Livre de Poche. 2013. ISBN 978-2-253-13140-3.