Peter Bryce

Peter Bryce | |

|---|---|

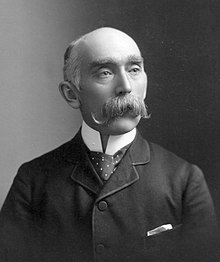

Bryce in 1899 | |

| Born | August 17, 1853 |

| Died | January 15, 1932 (aged 78) At sea near West Indies |

| Resting place | Beechwood Cemetery |

| Alma mater |

|

| Spouse |

Kate Lynde Pardon (m. 1882) |

| Children | 6 |

| Relatives | George Bryce (brother) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Public health |

Peter Henderson Bryce (August 17, 1853 – January 15, 1932) was a public health physician for the Ontario provincial and Canadian federal governments. As a public official he submitted reports that highlighted the mistreatment of Indigenous students in the Canadian Indian residential school system and advocated for the improvement of environmental conditions at the schools. He also worked on the health of immigrant populations in Canada.

Biography

[edit]Peter Bryce was born in Mount Pleasant, Ontario, on August 17, 1853.[1] He obtained his medical degree from the University of Toronto, where he studied natural science geology, and went on to study neurology in Paris. He lectured in 1878-79 at the Ontario Agricultural College in Guelph, Ontario, in science and applied chemistry.[2] Bryce served as the first secretary of the Ontario Board of Health from 1882 to 1904, and was also named as Ontario's first Chief Officer of Health in 1887 and Ontario Deputy Registrar General (in charge of Vital Statistics) in 1892.[3] He was a member of the Canadian Association for the Prevention of Tuberculosis, and in 1900 became the first Canadian president of the American Public Health Association.[4] Topics of his early papers included hypnotism, malaria, smallpox, diphtheria, sewage disposal, cholera, water supplies, ventilation, milk supply problems, tuberculosis, and the influence of forests on rainfall and health.[3]

In 1904 Bryce was appointed the Chief Medical Officer of the federal Departments of the Interior and Indian Affairs.[1][4] His 1905 and 1906 annual reports emphasized the abnormally high death rates for Indigenous peoples in Canada. In 1907 he wrote a "Report on the Indian Schools of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories" describing the health conditions of the Canadian residential school system in western Canada and British Columbia. This report was published without its recommendations, as Bryce discussed in his 1922 book The Story of a National Crime: Being a Record of the Health Conditions of the Indians of Canada from 1904 to 1921.

Bryce wrote that Indigenous children enrolled in residential schools were deprived of adequate medical attention and sanitary living conditions. He suggested improvements to national policies regarding the care and education of Indigenous peoples.[5][6] In a 1907 report Bryce cited an average mortality rate of between 15% and 24% among the schools' children and 42% in Aboriginal homes, where sick children were sometimes sent to die.[7]: 9 Bryce noted that the lack of certainty about the exact number of deaths was, in part, due to the official reports submitted by school principals and "defective way in which the returns had been made."[8]: 405

He appealed his forced retirement from the Civil Service in 1921 and was denied, subsequently publishing his suppressed report condemning the treatment of the Indigenous at the hands of the Department of Indian Affairs that had been given the responsibility under the British North America Act.[9]

Bryce died on January 15, 1932, while travelling in the West Indies.[10] Dr. Bryce is buried and honoured at Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa, the same location as Nicholas Flood Davin, author of the 1879 Davin Report that called for the establishment of a residential school system in Canada and Duncan Campbell Scott who served as deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913-1932. To assist reconciliation while also addressing historical and societal injustices, Beechwood Cemetery has a Reconciling History program, where “school children of all backgrounds...place paper hearts of gratitude and remembrance at Dr. Bryce’s grave site, as they do their own part for reconciliation."[11][12][13]

Publications

[edit]- Bryce, P. H. (1885). "Small-Pox in Canada, and the Methods of Dealing with it in the Different Provinces". Public Health Papers and Reports. 11. American Public Health Association: 166–181. PMC 2266210. PMID 19600241.

- "The duty of the public in dealing with tuberculosis: being a paper read before the Association of Executive Health Officers of Ontario, at Ottawa, October 27th, 1898". 27 October 1898. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- "Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs, for the fiscal year ended 30th June, 1905". Department of Indian Affairs. 1906. pp. 271–278. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- "Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs, for the fiscal year ended 30th June, 1906". Department of Indian Affairs. 1907. pp. 272–284. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- "Report on the Indian schools of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories". Internet Archive. Ottawa : Government Printing Bureau, 1907. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- "Insanity in immigrants: a paper read before the American Public Health Association, at Richmond, Va., October, 1909". Internet Archive. Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1910. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- "The illumination of Joseph Keeler, Esq., or, On, to the land!". Internet Archive. Boston, Mass.: The American Journal of Public Health, 1915. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- "The story of a national crime : being an appeal for justice to the Indians of Canada; the wards of the nation, our allies in the Revolutionary War, our brothers-in-arms in the Great War – Record of the Health Conditions of the Indians of Canada from 1904 to 1921". Internet Archive. Ottawa: James Hope and Sons. 1922. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

See also

[edit]- List of Canadian residential schools

- United States Indian Boarding School

- New Zealand Native schools

- Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- Canada - Institutional racism

Sources

[edit]Hay, Travis; Blackstock, Cindy; Kirlew, Michael (2020-03-02). "Dr. Peter Bryce (1853–1932): whistleblower on residential schools". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 192 (9). CMA Joule Inc.: E223–E224. doi:10.1503/cmaj.190862. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 7055949. PMID 32122982.

Bryce, Peter Henderson (2016). "Bryce, Peter Henderson". In Cook, Ramsay; Bélanger, Réal (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XVI (1931–1940) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

References

[edit]- ^ a b FitzGerald, J. G. (February 1932). "Doctor Peter H. Bryce". Canadian Public Health Journal. 23 (2): 88–91. JSTOR 41976579.

- ^ Lux, Maureen K. (2001). Medicine that walks : disease, medicine, and Canadian Plains native people, 1880 - 1940. Toronto [u.a.]: Univ. of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802082954. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ a b Morgan, Henry James (1898). The Canadian men and women of the time : a handbook of Canadian biography. Toronto: W. Briggs. pp. 122–123.

- ^ a b Dickin, Janice (2013). "Peter Henderson Bryce". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ "Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future - Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada" (PDF). The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 31 May 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Sproule-Jones, Megan (1996). "Crusading for the Forgotten: Dr. Peter Bryce, Public Health, and Prairie Native Residential Schools". Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 13 (2): 199–24. doi:10.3138/cbmh.13.2.199. PMID 11620073.

- ^ Hope and Healing: the Legacy of the Indian Residential School System (PDF). Ottawa: Legacy of Hope Foundation. March 2014. ISBN 978-1-77198-002-9. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2015). "Canada's Residential Schools: The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939" (PDF). Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Volume 1. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ Bryce, Peter Henderson (1922). The story of a national crime. Ottawa, Canada: J. Hope and Sons – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Who was Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce?". First Nations Child & Family Caring Society. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ Deachman, Bruce (14 August 2015). "Beechwood ceremony to honour medical officer's tenacity". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ Hay, Travis; Blackstock, Cindy; Kirlew, Michael (2020-03-02). "Dr. Peter Bryce (1853–1932): whistleblower on residential schools". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 192 (9). CMA Joule Inc.: E223–E224. doi:10.1503/cmaj.190862. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 7055949. PMID 32122982.

- ^ "Reconciling History with Canada's First Nations - Beechwood Cemetery's program of national healing through truth and education". Ottawa Citizen. 1970-01-01. Retrieved 2021-05-30.

External links

[edit]"He was a whistleblower, who exposed deadly conditions in residential schools". CBC News. 17 August 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

Pushed out and silenced, CBC Unreserved, April 20, 2020| access date= 19 May 2020 .https://www.cbc.ca/radio/unreserved/exploring-the-past-finding-connections-in-little-known-indigenous-history-1.5531914/pushed-out-and-silenced-how-one-doctor-was-punished-for-speaking-out-about-residential-schools-1.5534953

Fraser, Crystal; Logan, Tricia; Orford, Neil (17 July 2021). "A doctor's century-old warning on residential schools can help find justice for Canada's crimes". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 28 May 2022. Peter Henderson Bryce detailed to Ottawa how its colonial policies were killing children, but his report and a self-published pamphlet from 1922 went unheeded.