Political eras of the United States

| Part of a series on the |

| Political eras of the United States |

|---|

Political eras of the United States refer to a model of American politics used in history and political science to periodize the political party system existing in the United States.

The United States Constitution is silent on the subject of political parties. The Founding Fathers did not originally intend for American politics to be partisan. In Federalist Papers No. 9 and No. 10, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, respectively, wrote specifically about the dangers of domestic political factions. In addition, the first President of the United States, George Washington, was not a member of any political party at the time of his election or throughout his tenure as president.[1] Furthermore, he hoped that political parties would not be formed, fearing conflict and stagnation, as outlined in his Farewell Address.[2]

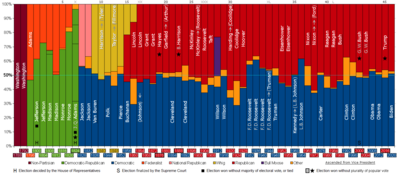

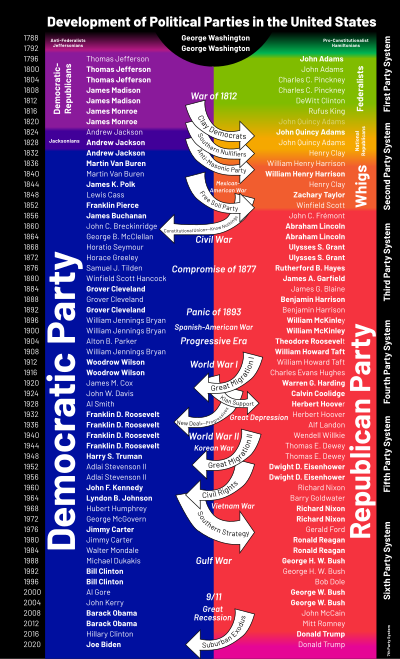

Generally, the political history of America can be divided into five hegemonic eras, which can be further divided into seven party systems which each follow a realignment. The political hegemonic eras are:

- 1789–1801: Federalist Era, dominated by the liberal-leaning Federalists, and their predecessors the Pro-Administration Faction, both based in the North. Pro-Administration Faction/Federalists have the full trifecta of government for 8 years of this period, while government was divided (between Congress and/or the Presidency) for 4 years.

- 1801–1861: Democratic Era, dominated by the conservative-leaning Democrats, and their predecessors the Democratic-Republicans, both based in the South to non-coastal North. Democratic-Republicans/Democrats have the full trifecta of government for 40 years of this period, government was divided for 19 years, and Whigs had a trifecta for 1 year.

- 1861–1933: Republican Era, dominated by socially liberal, economically conservative Republicans based in New England and the Great Lakes Region (and later the greater Rust Belt region and the Midwest). Republicans have the full trifecta of government for 36–40 years of this period (depending on the inclusion of Andrew Johnson's term[a] and the 1881 Senate term[b]), government was divided for 24–28 years, and Democrats had a trifecta for 8 years.

- 1933–1969: New Deal Democratic Era, dominated by a coalition of socially conservative Dems based in the South and economically progressive Dems based in the greater Rust Belt region, the Sun Belt and the Western Coast. This marks the beginning of the "party switch" – liberals in the North and Urban Cities slowly flip Democratic. Democrats have the full trifecta of government for 26 years, government was divided for 8 years, and Republicans had a trifecta for 2 years.

- 1969–Present: Divided Government Era, where the Federal Government is commonly divided (between Presidency and/or Congress) between liberal Democrats based in the North and West Coast & conservative Republicans based in the Midwest and South. This marks the finalization of the "party switch" – conservatives in the South and Rurals slowly flip Republican. As of November 2024, divided government has occurred for 40 years of this period, Democrats had a trifecta for 10 years, and Republicans held a trifecta for 6 years.

The seven party systems and their realignments which take place within these hegemonic eras are described in detail below:

First Party System: Federalist & Democrat Hegemony

[edit]The "First Party System" began in the 1790s with the 1792 re-election of George Washington and the 1796 election of John Adams, and ended in the 1820s with the presidential elections of 1824 and of 1828, resulting in Andrew Jackson's presidency.

George Washington's cabinet

[edit]The beginnings of the American two-party system emerged from George Washington's immediate circle of advisers, which split into two camps:

- Federalists – John Adams and Alexander Hamilton emerged as leaders of this camp; electoral base is in the North.

- Democratic-Republicans – Thomas Jefferson and James Madison emerged as leaders of this camp; the electoral base is in the South and Non-Coastal North.

Ironically, Hamilton and Madison wrote the Federalist Papers against political factions, but ended up being the core leaders in this emerging party system. Although distasteful to the participants, by the time John Adams and Thomas Jefferson ran for president in 1796, partisanship in the United States came to being.[3][4]

Era of Good Feelings

[edit]The disastrous Panic of 1819 and the Supreme Court's McCulloch v. Maryland reanimated the disputes over the supremacy of state sovereignty and federal power, between strict construction of the US Constitution and loose construction.[5] The Missouri Crisis in 1820 made the explosive political conflict between slave and free soil open and explicit.[6] Only through the adroit handling of the legislation by Speaker of the House Henry Clay was a settlement reached and disunion avoided.[7][8][9]

Jacksonian democracy

[edit]"Jacksonian democracy" is a term to describe the 19th-century political philosophy that originated with the seventh U.S. president, The United States presidential election of 1824 brought partisan politics to a fever pitch, with General Andrew Jackson's popular vote victory (and his plurality in the United States Electoral College being overturned in the United States House of Representatives).[citation needed]

With the decline in political consensus, it became imperative to revive Jeffersonian principles on the basis of Southern exceptionalism.[10][11] The agrarian alliance, North and South, would be revived to form Jacksonian Nationalism and the rise of the Democratic-Republican Party.[12][13] As a result, the Democratic-Republican Party split into a Jacksonian faction that was regionally and ideologically identical to the original party, which became the modern Democratic Party in the 1830s, and a Henry Clay faction that regionally and ideologically resembled the old Federalist Party, which was absorbed by Clay's Whig Party.[citation needed] The term "Jacksonian democracy" was in active use by the 1830s.[14]

Second Party System: Democrat Hegemony

[edit]Many historians and political scientists use "Second Party System" to describe American politics between the mid-1820s until the mid-1850s. The system was demonstrated by rapidly rising levels of voter interest (with high election day turnouts), rallies, partisan newspapers, and high degrees of personal loyalty to parties.[15][16] It was in full swing with the 1828 United States presidential election, since the Federalists shrank to a few isolated strongholds and the Democratic-Republicans lost unity during the buildup to the American Civil War. describe the operating in the United States.[17]

This party system marked the first in a series of political realignments, a process in which a prominent third party coalition, often one that wins >10% of the popular vote in multiple states in a presidential election, realigns into one of the major parties, allowing that major party to dominate the federal government and/or presidency for the following decades. The first and most significant Second Party System realignment was a realignment of the differing factions of the Democratic-Republican Party of the South and non-coastal North, particularly those factions that voted for Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay and William H. Crawford, into the new Jacksonian/Democratic Party.

The opposition, leftover Federalist-aligned voters who formed the Clay and Adams factions in the Coastal North, realigned into the National Republican Party in 1828. This northern base, alongside the wealthy slave owners of the Southern slave centers and the Anti-Masons in Vermont, Massachusetts, Northern New York state and Southern Pennsylvania, realigned into the newly formed Whig Party in 1836. With the fall of the Whig Party in 1856, the remaining Whig coalition (those not effected by the Free Soil movement in New England and the Great Lakes Region) realigned into the Know Nothing ticket that same year then realigned into the Constitutional Union Party in 1860 at the start of the next party system.

The political party system of the United states was dominated by two major parties:

- The Jacksonian Democrats led by Andrew Jackson. The Jacksonian Democrats stood for the "sovereignty of the people" as expressed in popular demonstrations, constitutional conventions, and majority rule as a general principle of governing,

- The Whig Party, assembled by Henry Clay from the National Republicans and from other opponents of Jackson. Whigs advocated the rule of law, written and unchanging constitutions, and protections for minority interests against majority tyranny.[18]

After taking office in 1829, President Andrew Jackson restructured a number of federal institutions. Jackson's professed philosophy became the nation's dominant political worldview for the remainder of the 1830s, helping his vice president (Martin Van Buren) secure election in the presidential election of 1836. In the presidential election of 1840, the "Whig Party" had its first national victory with the election of General William Henry Harrison, but he died shortly after assuming office in 1841. John Tyler (a self-proclaimed "Democrat") succeeded Harrison, as the first Vice President of the United States to ascend to the presidency via death of the incumbent.

Minor parties of the era included:

- the Anti-Masonic Party, an important innovator from 1827 to 1834

- the abolitionist Liberty Party in 1840

- the anti-slavery expansion Free Soil Party in 1848 and 1852.

Third Party System: Republican Hegemony

[edit]The "Third Party System" refers to the period which came into focus in the 1850s (during the leadup to the American Civil War) and ended in the 1890s. The issues of focus during this time: Slavery, the civil war, Reconstruction, race, and monetary issues.

The Third Party System was marked by a realignment of the Free Soil Party movement of New England and the Great Lakes Region into the Republican Party after the 1856 election, and a realignment of the more northern portion of Whigs, Constitutional Union voters and Know Nothing voters along the Coastal Midatlantic into the Democratic Party after the 1864 election.

It was dominated by the new Republican Party, which claimed success in saving the Union, abolishing slavery and enfranchising the freedmen, while adopting many Whig-style modernization programs such as national banks, railroads, high tariffs, homesteads, social spending (such as on greater Civil War veteran pension funding), and aid to land grant colleges. While most elections from 1876 through 1892 were extremely close, the opposition Democrats won only the 1884 and 1892 presidential elections (the Democrats also won the popular vote in the 1876 and 1888 presidential elections, but lost the electoral college vote), although from 1875 to 1895 the party usually controlled the United States House of Representatives and controlled the United States Senate from 1879 to 1881 and 1893–1895. Indeed, scholarally work and electoral evidence emphasizes that after the 1876 election the South’s former slave centers, which before the emancipation of Republican-voting African Americans was electorally dominated by voting wealthy slave owners who made up the southern base of Whigs, Know Nothings and Constitutional Unionists, realigned into the Democratic Party due to the end of Reconstruction; the overall national support for Reconstruction collapsed as well.[19] The northern and western states were largely Republican, except for the closely balanced New York, Indiana, New Jersey, and Connecticut. After 1876, the Democrats took control of the "Solid South".[20]

Historians and political scientists generally believe that the Third Party System ended in the mid-1890s, which featured profound developments in issues of American nationalism, modernization, and race. This period, the later part of which is often termed the Gilded Age, is defined by its contrast with the preceding and following eras.

Fourth Party System: Republican Hegemony

[edit]The "Fourth Party System" is the term used in political science and history for the period in American political history from the mid-1890s to the early 1930s, It was dominated by the Republican Party, excepting when 1912 split in which Democrats (led by President Woodrow Wilson) held the White House for eight years. American history texts usually call the period the Progressive Era. The concept was introduced under the name "System of 1896" by E. E. Schattschneider in 1960, and the numbering scheme was added by political scientists in the mid-1960s.[21]

The realignments that marked the beginning of the Fourth Party System was that of the Greenback Party, which dominated the greater Rust Belt region (which included upstate New York, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Baltimore), into the GOP after 1896, and the realignment of their ideological successor the Populist Party, which dominated the Midwest, into the Republican Party after the 1900 and 1904 elections.

The era began in the severe depression of 1893 and the extraordinarily intense election of 1896. It included the Progressive Era, World War I, and the start of the Great Depression. The Great Depression caused a realignment that produced the Fifth Party System, dominated by the Democratic New Deal coalition until the 1970s.

The central domestic issues concerned government regulation of railroads and large corporations ("trusts"), the money issue (gold versus silver), the protective tariff, the role of labor unions, child labor, the need for a new banking system, corruption in party politics, primary elections, the introduction of the federal income tax, direct election of senators, racial segregation, efficiency in government, women's suffrage, and control of immigration. Foreign policy centered on the 1898 Spanish–American War, Imperialism, the Mexican Revolution, World War I, and the creation of the League of Nations. Dominant personalities included presidents William McKinley (R), Theodore Roosevelt (R), and Woodrow Wilson (D), three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan (D), and Wisconsin's progressive Republican Robert M. La Follette, Sr.

The Fourth Party System ended with the Great Depression, a worldwide economic depression that started in 1929. A few years after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Herbert Hoover lost the 1932 United States presidential election to Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Fifth Party System: New Deal Democrat Hegemony

[edit]The Fifth Party System (1932–1976) describes a period in American history in which progressives in the North and conservative Democrats in the South joined a broad coalition called the "New Deal Coalition" to share control of government over the more business-aligned Republican Party, particularly as a result of the Republican Party's failure to contain the Great Depression while in power in the early 1930s.

The Fifth Party System began as a result of a realignment of the Progressive Party of the Western Coast and the greater Rust Belt region (which includes New York, Massachusetts, Baltimore and New Jersey), and a realignment of the Socialist Party of the Western Coast and Sun Belt, into the otherwise conservative Democratic Party after the 1932 and 1936 elections.

Key figures of the Fifth Party System include Franklin D. Roosevelt, the key founder of the New Deal coalition and president during most of the Great Depression and most of World War II; Harry S. Truman, successor to Franklin Roosevelt; John F. Kennedy; and civil rights champion Lyndon B. Johnson.

Because there has been no significant change of hands in Congress since the beginning of the Fifth Party System, historians have trouble placing dates and specifications for the modern party systems that succeed this one.

Later systems: Divided Government Era

[edit]The later party systems (with periods indicated in parentheses) include:

- Sixth Party System (1968 or 1980–2008 or 2020), known for the period in which Republicans used the "Southern strategy" to realign Dixiecrats from the South into the party, which began in 1964 and finalized in 1984. This allowed the party to gain dominant control of the Presidency after 1968 or 1980, and dominant control of Congress after the 1994 Republican Revolution. This party system is heavily dominated by ticket-splitting.

- Seventh Party System (2008 or 2020–present), a party system led by the realignment of Centrist Independent voters from the North and West who supported John B. Anderson and Ross Perot into the Democratic Party from 1996-2008, allowing the Democrats to gain dominant control of the Presidency. This party system is heavily dominated by polarization.

Notes

[edit]- ^ While President Andrew Johnson, elected through the Republican-aligned National Union Party after formerly being a War Democrat, and the Republican Congress were on good terms and cooperated the first few years of his presidency, the relationship grew increasingly strained due to Johnson's disagreements with Radical Republicans over the nature of Reconstruction. After the midterms, Congress would substantially break with Johnson and begin their first attempt at impeachment against him in January 1867, by which point Johnson's practical trifecta was gone.

- ^ From the start of Congress on March 4, 1881 to May 18 of that year, the Republicans held the Senate (and a trifecta) through the tie-breaking Vice President Arthur and through a caucus that included a Readjuster Senator. When both Republican New York senators resigned, the Republicans lost control of their trifecta and Congress ended their session. By the time Congress returned in September 1881 and the Senate reconvened with two new Republican New York senators, Vice President Arthur had succeeded to the Presidency and the Senate deadlocked. The Senate decided to give Republicans the important role of controlling the Senate committees, give the Democrat-caucusing Independent the mostly ceremonial role of president pro tempore, and leave the patronage appointments and other Senate office appointments to the Democrats.)

References

[edit]- ^ Chambers, William Nisbet (1963). Political Parties in a New Nation.

- ^ Washington's Farewell Address

- ^ Richard Hofstadter, The Idea of a Party System: The Rise of Legitimate Opposition in the United States, 1780–1840 (1970)

- ^ Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815 (Oxford History of the United States)

- ^ Dangerfield 1965, p. 97–98

- ^ Wilentz 2006, p. 217,219

- ^ Wilentz 2006, p. 42

- ^ Brown 1970, p. 25

- ^ Wilentz 2006, p. 240

- ^ Brown 1970, p. 23,24

- ^ Varon, Elizabeth R. (2008). Disunion!: The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789–1859. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 39,40.

- ^ Brown 1970, p. 22

- ^ Dangerfield 1965, p. 3

- ^ The Providence (Rhode Island) Patriot August 25, 1839, stated: "The state of things in Kentucky..is quite as favorable to the cause of Jacksonian democracy." cited in "Jacksonian democracy", Oxford English Dictionary (2019)

- ^ Brown 1999.

- ^ Wilentz 2006.

- ^ William G. Shade, "The Second Party System" in Paul Kleppner, et al. Evolution of American Electoral Systems (1983) pp 77–112.

- ^ Frank Towers, "Mobtown's Impact on the Study of Urban Politics in the Early Republic.". Maryland Historical Magazine 107 (Winter 2012) pp: 469–75, p 472, citing Robert E, Shalhope, The Baltimore Bank Riot: Political Upheaval in Antebellum Maryland (2009) p. 147

- ^ James E. Campbell, "Party Systems and Realignments in the United States, 1868–2004," Social Science History Fall 2006, Vol. 30, Iss. 3, pp. 359–86

- ^ Foner 1988.

- ^ To cite a standard political science college textbook: "Scholars generally agree that realignment theory identifies five distinct party systems with the following approximate dates and major parties: 1. 1796–1816, First Party System: Jeffersonian Republicans and Federalists; 2. 1840–1856, Second Party System: Democrats and Whigs; 3. 1860–1896, Third Party System: Republicans and Democrats; 4. 1896–1932, Fourth Party System: Republicans and Democrats; 5. 1932–, Fifth Party System: Democrats and Republicans." Robert C. Benedict, Matthew J. Burbank and Ronald J. Hrebenar, Political Parties, Interest Groups and Political Campaigns. Westview Press. 1999. Page 11.

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, Richard H. (1970). "The Missouri Crisis, Slavery, and the Politics of Jacksonianism". South Atlantic Quarterly: 55–72. Cited in Gatell, Frank Otto, ed. (1970). Essays on Jacksonian America. New York City: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Brown, David (Fall 1999). Jeffersonian Ideology And The Second Party System. Vol. 62. pp. 17–44.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Dangerfield, George (1965). The Awakening of American Nationalism: 1815–1828. New York City: Harper & Row.

- Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877.

- Wilentz, Sean (2006). The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln.