Prelude to the Iraq War

| Prelude to the Iraq War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War on terror and the Iraq War | |||||||

Clockwise from top-left: An American helicopter shadows a Russian oil tanker to enforce sanctions against Iraq; Two US F-16 Fighting Falcons prepare to depart Prince Sultan Air Base in Saudi Arabia for a patrol as part of Operation Southern Watch, 2000; An Iraqi surface-to-air missile firing at a coalition aircraft, July 2001; A UN weapons inspector in Iraq, 2002; President George Bush, surrounded by leaders of the House and Senate, announces the Joint Resolution to Authorize the Use of United States Armed Forces Against Iraq, 2 October 2002; US Marine M1A1 tank is off-loaded from a US Navy LCAC in Kuwait in February 2003; Anti war protest in London, 2002; US Secretary of State Colin Powell holding a model vial of anthrax while giving the presentation to the United Nations Security Council on 5 February 2003 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Coalition of the willing

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Shortly after the September 11 attacks, the United States under the administration of George W. Bush, actively pressed for military action against Iraq, claiming that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein was developing weapons of mass destruction and having ties with al-Qaeda. The United States and United Kingdom argued that Iraq's activities posed a threat to the international community.

During the 1990s, the U.S. and the U.K. pursued a policy of containment towards Iraq. Containment encompassed a United Nations inspections regime that was tasked with disarming Iraq of weapons of mass destruction, which was linked to an comprehensive embargo on that country. In addition, the U.S. and U.K. patrolled no fly zones that barred Iraqi aircraft from operating in northern and southern Iraq. However, by the end of the decade, containment eroded as relations became increasingly strained between the U.N. and Iraq, which ultimately culminated in the weapons inspectors being withdrawn from the country in late 1998. The U.S. and U.K. retaliated with a bombing campaign against Iraqi military targets. Following Desert Fox, Iraq openly challenged U.S. and U.K. aircraft patrolling the no fly zones, attempting to shoot down military aircraft. Concurrently, U.N. sanctions were becoming less enforced, as Iraq was able to manipulate the sanctions regime in its favor to convince more countries to lift the sanctions altogether.

As containment eroded, beginning in the late 1990s neoconservatives argued for the overthrow of Saddam Hussein's regime and democratization of Iraq. They justified overthrow on the basis that Ba'athist Iraq posed a direct threat to American security by threatening Middle East stability and secure access to oil with its weapons of mass destruction and missile programs, and that the United Nations was an ineffective tool in confronting this threat. Neoconservative advocacy would lead to the passing of the Iraq Liberation Act in late 1998, making regime change in Iraq as official U.S. policy. Following the election of George W. Bush as president in 2000, the U.S. moved towards a more aggressive Iraq policy. The Republican Party's campaign platform in the 2000 election called for "full implementation" of the Iraq Liberation Act as "a starting point" in a plan to "remove" Saddam.[1] Many neoconservatives would take up key positions in the Bush administration.

In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, elements within the Bush administration believed that Iraq shared responsibility for the attacks, as well as having ties to al-Qaeda. Believing that a state sponsor was involved, many within the administration concurrently harbored a distrust towards the U.S. intelligence community for underestimating threats, and instead preferred utilizing outside analysis and intelligence from the Iraqi opposition that alleged an Iraq-al-Qaeda connection, as well as allegations that Iraq was developing weapons of mass destruction. Although military action was initially deferred in favor of invading Afghanistan, from September 2002 the U.S. began to formally present its case for action against Iraq at the United Nations. In November, the UN Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1441, stating that Iraq was in material breach with its disarmament obligations and giving Iraq "a final opportunity to comply" that had been set out in several previous resolutions (Resolutions 660, 661, 678, 686, 687, 688, 707, 715, 986, and 1284).[2] Concurrently, an elaborate public relations campaign was waged to market military action to both the American and British publics, culminating in then-Secretary of State Colin Powell's February 2003 address to the Security Council.[3]

After failing to gain UN support for an UN authorization for an invasion, the U.S., together with the U.K. and small contingents from Australia, Poland, and Denmark, launched an invasion on 20 March 2003 under the authority of UN Security Council Resolution 660 and United Nations Security Council Resolution 678.[4] Following the invasion, no evidence of an active WMD program or ties to al-Qaeda was ever found.

Background

[edit]Pre-Gulf War

[edit]Throughout the Cold War, Iraq had been an ally of the Soviet Union, and there was a history of friction between Iraq and the United States.[5] The U.S. had backed Pahlavi Iran as means of maintaining Gulf stability, and the latter had been an adversary of Iraq. Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi distrusted the Ba'athist government in Iraq, which he considered a "bunch of thugs and murderers."[6] In April 1969, Iran abrogated the 1937 treaty over the Shatt al-Arab and Iranian ships stopped paying tolls to Iraq when they used the Shatt al-Arab.[7] The Shah argued that the 1937 treaty was unfair to Iran because almost all river borders around the world ran along the thalweg, and because most of the ships that used the Shatt al-Arab were Iranian.[8] Iraq threatened war over the Iranian move, but on 24 April 1969, an Iranian tanker escorted by Iranian warships (Joint Operation Arvand) sailed down the Shatt al-Arab, and Iraq—being the militarily weaker state—did nothing.[9] Mohammad Reza financed Kurdish separatist rebels in Iraq, and to cover his tracks, armed them with Soviet weapons which Israel had seized from Soviet-backed Arab regimes, then handed over to Iran at the Shah's behest. On 7 May 1972, the Shah told a visiting President Richard Nixon that the Soviet Union was attempting to dominate the Middle East via its close ally Iraq, and that to check Iraqi ambitions would also be to check Soviet ambitions.[10] Nixon agreed to support Iranian claims to have the thalweg in the Shatt al-Arab recognised as the border and to generally back Iran in its confrontation with Iraq.[10]

From October 1972 until the abrupt end of the Kurdish intervention after March 1975, the CIA "provided the Kurds with nearly $20 million in assistance," including 1,250 tons of non-attributable weaponry.[11] The main goal of U.S. policy-makers was to increase the Kurds's ability to negotiate a reasonable autonomy agreement with the government of Iraq.[12] To justify the operation, U.S. officials cited Iraq's support for international terrorism and its repeated threats against neighboring states, including Iran (where Iraq supported Baluchi and Arab separatists against the Shah) and Kuwait (Iraq launched an unprovoked attack on a Kuwaiti border post and claimed the Kuwaiti islands of Warbah and Bubiyan in May 1973), with Haig remarking: "There can be no doubt that it is in the interest of ourselves, our allies, and other friendly governments in the area to see the Ba'thi regime in Iraq kept off balance and if possible overthrown."[13][14] In 1975, Iran and Iraq signed the Algiers Accord, which granted Iran equal navigation rights in the Shatt al-Arab as the thalweg was now the new border, while Mohammad Reza agreed to end his support for Iraqi Kurdish rebels.[15]

In February 1979, the Iranian Revolution ousted the American-backed Shah from Iran, losing the United States one of its most powerful allies.[16] That November, the revolutionary group Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, angered that the ailing Shah had been allowed into the United States for medical treatment, occupied the American embassy in Tehran and took American diplomats hostage with the advance approval of the leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.[17] Diplomatic relations between Iran and the United States were severed shortly after.[18] Concurrently, Iraqi-Iranian relations were deteriorating as Khomeini was attempting to export the Islamic Revolution to the Arab world, calling for existing regimes to be overthrown in Islamist revolutions. Saddam, a secularist and an Arab nationalist, perceived Iran's Shia Islamism as an immediate and existential threat to his Ba'ath Party and thereby to Iraqi society as a whole.[19]

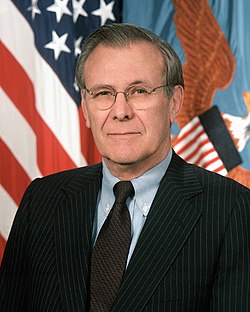

Iraq invaded Iran on 22 September 1980, first launching airstrikes on numerous targets in Iran, including the Mehrabad Airport of Tehran, before occupying the oil-rich Iranian province of Khuzestan, which also has a sizable Arab minority.[20] The invasion was initially successful, as Iraq captured more than 25,900 km2 of Iranian territory by 5 December 1980.[21][20] After making some initial gains, Iraq's troops began to suffer losses from human wave attacks by Iran. By mid-1982, the war's momentum had shifted decisively in favor of Iran, which invaded Iraq to depose Saddam's government.[22][23] Although the U.S. was officially neutral at first, the prospect of an expansionist Iran alarmed many in the Reagan administration, leading the U.S. to abandon neutrality.[24] The U.S. then joined in alongside the Soviet Union, France, China, and the Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait to bolster Iraq, helping to provide several billion dollars' worth of economic aid, the sale of dual-use technology, non-U.S. origin weaponry, military intelligence, and special operations training.[25][26] In a US bid to open full diplomatic relations with Iraq, the country was removed from the US list of State Sponsors of Terrorism.[27] Following this, the United States extended credits to Iraq for the purchase of American agricultural commodities,[28] the first time this had been done since 1967. More significantly, in 1983 the Baathist government hosted United States special Middle East envoy Donald Rumsfeld, to cultivate U.S.-Iraq ties. All of these initiatives prepared the ground for Iraq and the United States to reestablish diplomatic relations in November 1984. Iraq was the last of the Arab countries to resume diplomatic relations with the U.S.[29]

The U.S. provided critical battle planning assistance at a time when U.S. intelligence agencies knew that Iraqi commanders would employ chemical weapons in waging the war, according to senior military officers with direct knowledge of the program. The U.S. carried out this covert program even as it publicly condemned Iraq for its use of poison gas, especially after Iraq attacked Kurdish villagers in Halabja in March 1988.[30] According to Iraqi documents, assistance in developing chemical weapons was obtained from firms in many countries, including the United States, West Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and France. A report stated that Dutch, Australian, Italian, French and both West and East German companies were involved in the export of raw materials to Iraqi chemical weapons factories.[31]

By the time the ceasefire with Iran was signed in August 1988, Iraq was heavily debt-ridden and tensions within society were rising.[32] Most of its debt was owed to Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.[33] Relations with Kuwait began to deteriorate as the nation was pumping large amounts of oil, and thus keeping prices low, when Iraq needed to sell high-priced oil from its wells to pay off its huge debt.[34] Iraq's relations with other Arab neighbors, particularly Egypt, were degraded by mounting violence in Iraq against expatriate groups, who were well-employed during the war, by unemployed Iraqis, among them demobilized soldiers. Meanwhile, relations with the U.S. began to deteriorate following the revelations that the U.S. had covertly provided Iran with weaponry.[20] This political scandal became known as the Iran–Contra affair.[35] The US also began to condemn Iraq's human rights record, including the well-known use of torture.[36] The UK also condemned the execution of Farzad Bazoft, a journalist working for the British newspaper The Observer.[37] Following Saddam's declaration that "binary chemical weapons" would be used on Israel if it used military force against Iraq, Washington halted part of its funding.[38] A UN mission to the Israeli-occupied territories, where riots had resulted in Palestinian deaths, was vetoed by the US, making Iraq deeply skeptical of US foreign policy aims in the region, combined with the reliance of the US on Middle Eastern energy reserves.[39] Saddam threatened force against Kuwait and the UAE, saying: "The policies of some Arab rulers are American ... They are inspired by America to undermine Arab interests and security."[40] The US sent aerial refuelling planes and combat ships to the Persian Gulf in response to these threats.[41]

The US ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, met with Saddam in an emergency meeting on 25 July 1990, where the Iraqi leader attacked American policy with regards to Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates (UAE):[42]

So what can it mean when America says it will now protect its friends? It can only mean prejudice against Iraq. This stance plus maneuvers and statements which have been made has encouraged the UAE and Kuwait to disregard Iraqi rights. If you use pressure, we will deploy pressure and force. We know that you can harm us although we do not threaten you. But we too can harm you. Everyone can cause harm according to their ability and their size. We cannot come all the way to you in the US, but individual Arabs may reach you. We do not place America among the enemies. We place it where we want our friends to be and we try to be friends. But repeated American statements last year made it apparent that America did not regard us as friends.

Glaspie replied:[42]

I know you need funds. We understand that and our opinion is that you should have the opportunity to rebuild your country. But we have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait. ... Frankly, we can only see that you have deployed massive troops in the south. Normally that would not be any of our business. But when this happens in the context of what you said on your national day, then when we read the details in the two letters of the Foreign Minister, then when we see the Iraqi point of view that the measures taken by the UAE and Kuwait is, in the final analysis, parallel to military aggression against Iraq, then it would be reasonable for me to be concerned.

Saddam stated that he would attempt last-ditch negotiations with the Kuwaitis but Iraq "would not accept death."[42] US officials attempted to maintain a conciliatory line with Iraq, indicating that while George H. W. Bush and James Baker did not want force used, they would not take any position on what was viewed as a border dispute between Iraq and Kuwait, and didn't want to become involved.[43]

Saddam's foreign minister Tariq Aziz later told PBS Frontline in 1996 that the Iraqi leadership was under "no illusion" about America's likely response to the Iraqi invasion: "She [Glaspie] didn't tell us anything strange. She didn't tell us in the sense that we concluded that the Americans will not retaliate. That was nonsense you see. It was nonsense to think that the Americans would not attack us."[44] And in a second 2000 interview with the same television program, Aziz said:

There were no mixed signals. We should not forget that the whole period before August 2 witnessed a negative American policy towards Iraq. So it would be quite foolish to think that, if we go to Kuwait, then America would like that. Because the American tendency ... was to untie Iraq. So how could we imagine that such a step was going to be appreciated by the Americans? It looks foolish, you see, this is fiction. About the meeting with April Glaspie—it was a routine meeting...She didn't say anything extraordinary beyond what any professional diplomat would say without previous instructions from his government...what she said were routine, classical comments on what the president was asking her to convey to President Bush. He wanted her to carry a message to George Bush—not to receive a message through her from Washington.[45]

Gulf War and Iraqi Uprisings

[edit]

On 2 August 1990, Saddam invaded Kuwait, initially claiming assistance to "Kuwaiti revolutionaries", thus sparking an international crisis. On 4 August an Iraqi-backed "Provisional Government of Free Kuwait" was proclaimed, but a total lack of legitimacy and support for it led to an 8 August announcement of a "merger" of the two countries. On 28 August Kuwait formally became the 19th Governorate of Iraq. Just two years after the 1988 Iraq and Iran truce, "Saddam did what his Gulf patrons had earlier paid him to prevent." Having removed the threat of Iranian fundamentalism he "overran Kuwait and confronted his Gulf neighbors in the name of Arab nationalism and Islam."[46] Saddam justified the invasion of Kuwait in 1990 by claiming that Kuwait had always been an integral part of Iraq and only became an independent nation due to the interference of the British Empire.[47] Soon after his conquest of Kuwait, Saddam began verbally attacking the Saudis. He argued that the US-supported Saudi state was an illegitimate and unworthy guardian of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. He combined the language of the Islamist groups that had recently fought in Afghanistan with the rhetoric Iran had long used to attack the Saudis.[48]

The Bush administration had at first been indecisive with an "undertone ... of resignation to the invasion and even adaptation to it as a fait accompli" until the UK's prime minister Margaret Thatcher[49] played a powerful role, reminding the President that appeasement in the 1930s had led to war, that Saddam would have the whole Gulf at his mercy along with 65 percent of the world's oil supply, and famously urging President Bush "not to go wobbly".[49] Once persuaded, US officials insisted on a total Iraqi pullout from Kuwait, without any linkage to other Middle Eastern problems, accepting the British view that any concessions would strengthen Iraqi influence in the region for years to come.[50] Within hours of the invasion, Kuwaiti and US delegations requested a meeting of the UN Security Council, which passed Resolution 660, condemning the invasion and demanding a withdrawal of Iraqi troops.[51][52][clarification needed][53] On 6 August, Resolution 661 placed economic sanctions on Iraq.[54][51][55] Resolution 665[54] followed soon after, which authorized a naval blockade to enforce the sanctions. It said the "use of measures commensurate to the specific circumstances as may be necessary ... to halt all inward and outward maritime shipping in order to inspect and verify their cargoes and destinations and to ensure strict implementation of resolution 661."[56][57]

Acting on the Carter Doctrine policy, and out of fear the Iraqi Army could launch an invasion of Saudi Arabia, Bush quickly announced that the US would launch a "wholly defensive" mission to prevent Iraq from invading Saudi Arabia, under the codename Operation Desert Shield. The operation began on 7 August 1990, when US troops were sent to Saudi Arabia, due also to the request of its monarch, King Fahd, who had earlier called for US military assistance.[58] This "wholly defensive" doctrine was quickly abandoned when, on 8 August, Iraq declared Kuwait to be Iraq's 19th province and Saddam named his cousin, Ali Hassan Al-Majid, as its military-governor.[59]

On 29 November 1990, the Security Council passed Resolution 678, which gave Iraq until 15 January 1991 to withdraw from Kuwait, and empowered states to use "all necessary means" to force Iraq out of Kuwait after the deadline.[citation needed] Cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union made possible the passage of resolutions in the United Nations Security Council giving Iraq a deadline to leave Kuwait and approving the use of force if Saddam did not comply with the timetable.[60] A US-led coalition of forces opposing Iraq's aggression was formed, consisting of forces from 42 countries.[61] Saddam ignored the Security Council deadline.[62] Backed by the Security Council, a US-led coalition launched round-the-clock missile and aerial attacks on Iraq, beginning 16 January 1991.[62] Israel, though subjected to attack by Iraqi missiles, refrained from retaliating in order not to provoke Arab states into leaving the coalition.[62] A ground force consisting largely of US and British armored and infantry divisions ejected Saddam's army from Kuwait in February 1991 and occupied the southern portion of Iraq as far as the Euphrates.[62]

As the Gulf War reached its end, the U.S. attempted to instigate the overthrow of Saddam Hussein via a military coup. On February 15, 1991, President of the United States, George H. W. Bush, made a speech targeting Iraqis via Voice of America radio. Bush stated:[63]

There is another way for the bloodshed to stop: and that is, for the Iraqi military and the Iraqi people to take matters into their own hands and force Saddam Hussein, the dictator, to step aside and then comply with the United Nations' resolutions and rejoin the family of peace-loving nations.[64]

On March 1, 1991, one day after the Gulf War ceasefire, a revolt broke out in Basra against the Iraqi government. The uprising spread within days to all of the largest Shia cities in southern Iraq: Najaf, Amarah, Diwaniya, Hilla, Karbala, Kut, Nasiriyah and Samawah. The rebellions were encouraged by an airing of "The Voice of Free Iraq" on 24 February 1991, which was broadcast from a CIA-run radio station out of Saudi Arabia. The Arabic service of the Voice of America supported the uprising by stating that the rebellion was well supported, and that they would soon be liberated from Saddam.[65] In the North, Kurdish leaders took American statements that they would support an uprising to heart, and began fighting, hoping to trigger a coup d'état. However, when no US support came, Iraqi generals remained loyal to Saddam and brutally crushed the Kurdish uprising and the uprising in the south.[66] Millions of Kurds fled across the mountains to Turkey and Kurdish areas of Iran. On April 5, the Iraqi government announced "the complete crushing of acts of sedition, sabotage and rioting in all towns of Iraq." An estimated 25,000 to 100,000 Iraqis were killed in the uprisings.[67][68]

Many Iraqi and American critics accused President George H. W. Bush and his administration of encouraging and abandoning the rebellion after halting Coalition forces at Iraq's southern border with Kuwait at the end of the Gulf War.[69][70] In 1996, Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, admitted in his book My American Journey that, while Bush's rhetoric "may have given encouragement to the rebels", "our practical intention was to leave Baghdad enough power to survive as a threat to Iran that remained bitterly hostile toward the United States."[71] Coalition Commander Norman Schwarzkopf Jr. has expressed regret for negotiating a ceasefire agreement that allowed Iraq to use helicopters (to compensate for the destroyed infrastructure), but also suggested a move to support the uprisings would have empowered Iran.[72] Bush's national security adviser, Brent Scowcroft, told ABC's Peter Jennings "I frankly wished [the uprisings] hadn't happened ... we certainly would have preferred a coup."[73] Scowcroft later stated in a 2001 interview that removing Hussein from power was not an objective of any United Nations Security Council resolution related to the Gulf War or the 1991 Iraq AUMF Resolution, and that it was a fundamental interest of the United States to maintain a unified Iraq and to keep a balance in the region.[74]

In 1992, the US Defense Secretary during the war, Dick Cheney, made the same point:

I would guess if we had gone in there, we would still have forces in Baghdad today. We'd be running the country. We would not have been able to get everybody out and bring everybody home.

And the final point that I think needs to be made is this question of casualties. I don't think you could have done all of that without significant additional US casualties, and while everybody was tremendously impressed with the low cost of the (1991) conflict, for the 146 Americans who were killed in action and for their families, it wasn't a cheap war.

And the question in my mind is, how many additional American casualties is Saddam [Hussein] worth? And the answer is, not that damned many. So, I think we got it right, both when we decided to expel him from Kuwait, but also when the President made the decision that we'd achieved our objectives and we were not going to go get bogged down in the problems of trying to take over and govern Iraq.[75]

Containment

[edit]| Events leading up to the Iraq War |

|---|

|

|

With Saddam remaining firmly in power, the U.S. now had to create a long term policy to prevent Saddam from ever threatening Gulf stability again. The U.S. subsequently created a policy of containment against Iraq, which relied on three pillars; utilizing no-fly zones, sanctions, and forcing disarmament. In addition the U.S. continued to explore the possibility of ousting Saddam in a coup. By the end of the 1990s however, the containment strategy was put into question amidst rising challenges that Iraq increasingly posed.[76]

Sanctions & disarmament

[edit]

On 6 August 1990, four days after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) placed a comprehensive embargo on Iraq. Security Council Resolution 661 banned all trade and financial resources with both Iraq and occupied Kuwait except for medicine and "in humanitarian circumstances" foodstuffs, the import of which was tightly regulated. Sanctions barred Iraq from selling its oil onto the global market, import military technology.[77] A Multinational Interception Force was organized and led by the U.S. to intercept, inspect and possibly impound vessels, cargoes and crews suspected of carrying freight to or from Iraq.[78] Following the Gulf War, Resolution 687 amended the embargo to include eliminating weapons of mass destruction and extended-range ballistic missiles, prohibiting any support for terrorism, and forcing Iraq to pay war reparations to Kuwait and all foreign debt.[77][79] The resolution established the United Nations Special Commission to oversee and monitor Iraq's disarmament.[80] Sanctions would only be lifted if Iraq disarmed.[81] The powers given to UNSCOM inspectors in Iraq were: "unrestricted freedom of movement without advance notice in Iraq"; the "right to unimpeded access to any site or facility for the purpose of the on-site inspection...whether such site or facility be above or below ground"; "the right to request, receive, examine, and copy any record data, or information...relevant to" UNSCOM's activities; and the "right to take and analyze samples of any kind as well as to remove and export samples for off-site analysis".[82]

Iraq initially attempted to conceal their WMD programs, hoping to ride the inspections out after a period of time. But UN inspections proved to be far more through and stringent than what Saddam had originally anticipated, and was forced to begrudgingly accept their presence and allow the inspectors to destroy Iraq's arms. Unbeknownst to the UN however, Saddam gave orders to his second in command Hussein Kamel (who helped head Iraq's WMD and military industries) in July 1991, to covertly destroy much of Iraq's undeclared stocks of weapons of mass destruction and related capabilities. The decision to secretly destroy weapons and material without UN verification would come to greatly harm Iraq's credibility with the UN in the years ahead, for the lack of verification convinced many in the UN and other nations that Saddam continued to develop and retain significant stockpiles of WMD.[81] After the invasion, Hans Blix who headed UN disarmament efforts in Iraq in 2002-2003, wrote in his book that Saddam may have been weary that the inspectors (who worked closely with foreign intelligence agencies) would have uncovered military and regime secrets that could have undermined the regime, and also wanted to retain some deliberate ambiguity to keep potential enemies at bay.[83] Similarly, when interrogated by the FBI in 2004, Saddam asserted that the majority of Iraq's WMD stockpiles had been destroyed in the 1990s by UN inspectors, and the remainder were destroyed unilaterally by Iraq; the illusion of maintaining a WMD program and WMDs was maintained as a deterrent against possible Iranian invasion.[84] An FBI agent who interrogated Saddam during this time also speculated that while Iraq may not have possessed WMDs after the 1990s, Saddam may have intended to restart his WMD programs if given the opportunity to do so in the future, as Iraq also attempted to keep intact their scientific research and infrastructure.[84][81]

With the UN assuming that WMD stockpiles and programs continued to exist, the sanctions against Iraq were subsequently prolonged. The sanctions inflicted significant damage onto the country, as GDP plummeted from US$44.36 billion in 1990 to US$9 billion by 1995, inflation rose to 387%, and wiped out Iraq's middle class. Sanctions also caused high rates of malnutrition, shortages of medical supplies, diseases from lack of clean water, lengthy power outages, and the near collapse of the education system.[81][85][86][87] During the 1990s and 2000s, many surveys and studies concluded that excess deaths in Iraq—specifically among children under the age of 5—greatly increased during the sanctions at varying degrees.[85][88][89] On the other hand, several later surveys conducted in cooperation with the post-Saddam government during the U.S.-led occupation of Iraq "all put the U5MR in Iraq during 1995–2000 in the vicinity of 40 per 1000," suggesting that "there was no major rise in child mortality in Iraq after 1990 and during the period of the sanctions."[90][91]

Nevertheless, the effects of sanctions caused widespread outrage globally and with it, came great pressure to soften the sanctions altogether. Iraq further intensified the pressure by heavily publicizing the deprivation caused by sanctions, and threatened to cutoff cooperation with UNSCOM unless the sanctions would be lifted.[81] Security Council Resolution 706 of 15 August 1991 was introduced to allow the sale of Iraqi oil in exchange for food.[92] Security Council Resolution 712 of 19 September 1991 confirmed that Iraq could sell up to US$1.6 billion in oil to fund an Oil-For-Food Programme (OFFP).[93] Saddam initially refused, believing that it would lift pressure on the UNSC to lift sanctions completely. As a result, Iraq was effectively barred from exporting oil to the world market for several years.[94] By 1995, the deteriorating conditions forced Saddam to change his mind and accept OFFP.[81] Under the OFFP, the UN states that "Iraq was permitted to sell $2 billion worth of oil every six months, with two-thirds of that amount to be used to meet Iraq's humanitarian needs. Later on, the limits imposed on oil exports were loosened, then removed altogether. The share of revenue allocated to humanitarian relief increased to 72%;[95][96] 25% of the proceeds (which were held in escrow[94]) were redirected to a Kuwaiti reparations fund, and 3% to UN programs related to Iraq.[95] The first shipments of food arrived in March 1997, with medicines following in May 1997.[97] The UN recounts that "Over the life of the Programme, the Security Council expanded its initial emphasis on food and medicines to include infrastructure rehabilitation".[95] The OFFP allowed the Iraqi economy to stabilize as it led to the inflow of hard currency and revitalized trade with their neighbors, which helped reduce inflation. Iraq's gross domestic product increased from US$10.8 billion in 1996 to US$30.8 billion in 2000.[86]

Meanwhile, relations with UNSCOM became increasingly strained. By the summer of 1995, Iraq attempted to end the sanctions and inspections by promising UNSCOM that if their upcoming June 1995 report to the Security Council declared that Iraq complied in the nuclear and chemical fields, then Iraq would disclose information about their biological programs, which they denied weaponizing. Saddam then threatened to cutoff cooperation with UNSCOM unless the sanctions would be lifted.[81] But in August, Hussein Kamel defected alongside his brother, their wives (who were Saddam's daughters) and children to Jordan. Cooperating with UNSCOM, Kamel revealed that the Iraqi WMD programs was far more sophisticated than Iraq was willing to admit, and that the biological program was for weaponization.[98][81] In an effort to limit the damage of Kamel's defection, the regime took inspectors to Kamel's farm to 'uncover' WMD-related documents which allowed UNSCOM to access more information that had previously been withheld. But the defection forced UNSCOM to take a more aggressive posture towards Iraq, demanding inspections of more sensitive regime sites such as presidential palaces, of which Iraq was unwilling to easily accept. UNSCOM now believed that Iraq was deliberately deceiving the inspectors and choosing non-compliance with disarmament. The latter decided to hinder inspections of sensitive sites and documentation.[81]

By 1998, Iraq's relations with UNSCOM had reached a nadir, despite attempts by Secretary-General Kofi Annan to repair the relationship. Saddam and senior regime leaders realized that Iraq was unlikely to ever satisfy the UN's requirements for disarmament and subsequently cutoff cooperation with UNSCOM and the IAEA in late 1998. Although it was temporarily revoked after an American military buildup, relations were so strained that it never recovered. After UNSCOM reported to the UNSC on December 15 that Iraq had failed to comply, the U.S. and U.K. launched a bombing campaign to cripple Iraq's WMD programs and regime. The inspectors had been withdrawn beforehand, and Iraq vowed to never to allow them back. In addition, Saddam had issued a "secret order" that Iraq did not have to abide by any UN Resolution since in his view "the United States had broken international law". No inspections were carried out between 1998-2002.[81] Concurrently, Iraq began to leverage both its oil reserves and the OFFP to convince more countries to oppose the sanctions. Lax UN financial oversight over the OFFP allowed Iraq to corrupt the sanctions regime, handing out favorable oil contracts and allocations to states and individuals opposing the sanctions, including China, Russia, and France on the Security Council. This was fueled by continuing publicity of the hardships of Iraqis under sanctions.[81] The government even tried to prevent benefits from flowing to Shi'ite areas in southern Iraq to persuade more countries to oppose the sanctions.[86] Iraq felt that degrading sanctions without inspections were more preferable than accepting sanctions with inspections. Iraq used the money to further bolster the regime and its military, being able to increasingly import proscribed goods. In 1999, UNSCOM was replaced with the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission.[81]

Iraqi no-fly zones & other military actions

[edit]In March and early April, nearly two million Iraqis, 1.5 million of them Kurds,[99] escaped from strife-torn cities to the mountains along the northern borders, into the southern marshes, and to Turkey and Iran.[100] Their exodus was sudden and chaotic with thousands of desperate refugees fleeing on foot, on donkeys, or crammed onto open-backed trucks and tractors. Many were gunned down by Republican Guard helicopters, which deliberately strafed columns of fleeing civilians in a number of incidents in both the north and south.[69] Numerous refugees were also killed or maimed by stepping on land mines planted by Iraqi troops near the eastern border during the war with Iran. According to the U.S. Department of State and international relief organizations, between 500 and 1,000 Kurds died each day along Iraq's Turkish border.[100] According to some reports, up to hundreds of refugees died each day along the way to Iran as well.[101]

Fearful that Saddam would launch another wide-scale repression campaign like that of the Al-Anfal campaign in the late 1980s, the U.S.-led coalition created a no-fly zone in Northern Iraq to prevent aerial attacks by the Iraqis on the Kurds. On 3 March, General Norman Schwarzkopf warned the Iraqis that Coalition aircraft would shoot down Iraqi military aircraft flying over the country. On 20 March, a US F-15C Eagle fighter aircraft shot down an Iraqi Air Force Su-22 Fitter fighter-bomber over northern Iraq. On 22 March, another F-15 destroyed a second Su-22 and the pilot of an Iraqi PC-9 trainer bailed out after being approached by US fighter planes. On 5 April, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 688, calling on Iraq to end repression of its civilian population. On 6 April, Operation Provide Comfort began to bring humanitarian relief to the Kurds. Alongside aerial enforcement by the U.S., U.K., and France, was the delivery of humanitarian relief of over an estimated 1 million Kurdish refugees by a 6-nation airlift operation commanded from Incirlik Air Base in Turkey involving forces from the US, UK, France, Germany, Canada, and Italy.[102] As a result of these efforts, Iraq withdrew from Iraqi Kurdistan in October 1991. Provide Comfort was later superseded by Operation Northern Watch, without French participation.[103]

In southeastern Iraq, thousands of civilians, army deserters, and rebels began seeking precarious shelter in remote areas of the Hawizeh Marshes straddling the Iranian border. After the uprising, the Marsh Arabs were singled out for mass reprisals,[104] accompanied by ecologically catastrophic drainage of the Iraqi marshlands and the large-scale and systematic forcible transfer of the local population. A large scale government offensive attack against the refugees estimated 10,000 fighters and 200,000 displaced persons hiding in the marshes began in March–April 1992, using fixed-wing aircraft; a U.S. Department of State report claimed that Iraq dumped toxic chemicals in the waters in an effort to drive out the opposition.[100] Concurrently, Iraqi media declared on August 2, 1992 (The 2nd Anniversary of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait) that Kuwait was their 19th province and that they would invade again. Shortly thereafter, Iraqi troops began exchanging fire and making incursions into Kuwait.[105][106]

A no-fly zone up to the 32nd Parallel was enacted by the U.S., U.K., and France on August 26, 1992, with U.S. Navy F/A-18C Hornets of Carrier Air Wing Five from the aircraft carrier USS Independence being the first to fly into the zone. There were at least 70 fixed aircraft of the Iraqi Air Force assumed to be based in the No-Fly Zone at the time.[107] Iraq frequently challenged both no-fly zones, firing on coalition aircraft, and flying helicopters and aircraft into the zones. The coalition often retaliated by bombing Iraqi air defense sites and/or shooting down Iraqi aircraft.[108][109][110]

In late April 1993, the United States asserted that Saddam Hussein had attempted to have former President George H. W. Bush assassinated during a visit to Kuwait on April 14–16.[111] On June 26, as per order of then-President Clinton, U.S. warships stationed in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea launched a cruise missile attack at the Iraqi Intelligence Service building in downtown Baghdad in response to Iraq's plot to assassinate former President George H. W. Bush.[112] Actions in the no-fly zones decreased meanwhile, as Iraq halted firing onto aircraft.

In October 1994, Iraq once again began mobilizing around 64,000 Iraqi troops near the Kuwaiti border.[113][114] The U.S. responded by deploying by building up troop presence in the Persian Gulf to deter a second invasion of Kuwait. Iraq subsequently withdrew its troops from the border.[115]

When fighting broke out between the Kurdish PUK and KDP factions in 1996, the latter decided to ask for assistance from the Iraqi government who, seeing an opportunity to retake northern Iraq, accepted. On 31 August, 30,000 Iraqi troops, spearheaded by an armored division of the Iraqi Republican Guard, attacked the PUK-held city of Erbil, which was defended by 3,000 PUK Peshmerga led by Korsat Rasul Ali, in conjunction with KDP forces. Erbil was captured, and Iraqi troops executed 700 PUK and Iraqi National Congress prisoners of war in a field outside the city. After installing the KDP in control of Erbil, Iraqi Army troops withdrew from the Kurdish region back to their initial positions. The KDP drove the PUK from its other strongholds, and with additional Iraqi Army help, captured Sulaymaniyah on 9 September. Jalal Talabani and the PUK retreated to the Iranian border, and American forces evacuated 700 Iraqi National Congress personnel and 6,000 PUK members out of northern Iraq.[116][117] On 13 October, Sulaymaniyah was recaptured by the PUK, allegedly with support of Iranian forces.[118]

The attacks stoked fears that Saddam intended to launch a genocidal campaign against the Kurds similar to the campaigns of 1988 and 1991. The Clinton administration, unwilling to allow the Iraqi government to regain control of Iraqi Kurdistan, began Operation Desert Strike on 3 September, when American ships and B-52 Stratofortress bombers launched 27 cruise missiles at air defense sites in southern Iraq. The next day, 17 more cruise missiles were launched from American ships against Iraqi air defense sites. The United States also deployed strike aircraft and an aircraft carrier to the Persian Gulf region, and the extent of the southern no-fly zone was moved northwards to the 33rd parallel.[119]

In December 1998, the U.S. and U.K. initiated Operation Desert Fox, a four-day bombing campaign of Iraqi regime and military targets after Iraqi cooperation with UNSCOM collapsed. Prior to this, France ended their participation in the no-fly zones, arguing that they were maintained too long and were ineffective. Following the bombing, Iraq declared that they no longer recognized the no-fly zones, resuming their efforts to shoot down coalition aircraft. This marked an increased level of combat between Iraq and the coalition, as coalition warplanes retaliated attempted shoot downs by further bombing air defense sites.[120][121]

Attempts at regime change

[edit]In May 1991, U.S. President George H. W. Bush signed a presidential finding directing the Central Intelligence Agency to create conditions for Hussein's removal from power. Coordinating anti-Saddam groups was an important element of this strategy and the Iraqi National Congress (INC), led by Ahmed Chalabi, was the main group tasked with this purpose. The name INC was reportedly coined by public relations expert John Rendon (of the Rendon Group agency) and the group received millions in covert funding in the 1990s, and then about $8 million a year in overt funding after the passage of the Iraq Liberation Act in 1998. INC represented the first major attempt by opponents of Saddam to join forces, bringing together Kurds of all religions, Sunni and Shi'ite Arabs (both Islamic fundamentalist and secular) as well as non-Muslim Arabs; additionally monarchists, nationalists and ex-military officers.[122] In June 1992, nearly 200 delegates from dozens of opposition groups met in Vienna, along with Iraq's two main Kurdish militias, the rival Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). In October 1992, major Shi'ite groups, including the SCIRI and al-Dawa, came into the coalition and INC held a pivotal meeting in Kurdish-controlled northern Iraq, choosing a Leadership Council and a 26-member executive council.

At the Vienna conference, the INC made Ahmed Chalabi, a secular Shi'ite Iraqi-American and mathematician by training as its president. Chalabi was previously responsible for the 1989 collapse of Jordanian Petra Bank, which caused a $350 million bail-out by the Central Bank of Jordan and accused of embezzlement and false accounting.[123] Chalabi fled the country in the trunk of a car owned by Prince Hassan of Jordan.[124] He was convicted and sentenced in absentia for bank fraud by a Jordanian military tribunal to 22 years in prison. Chalabi maintained that his prosecution was a politically motivated effort to discredit him sponsored by Saddam Hussein.[125]

In 1993 Chalabi had begun promoting a plan for regime change called “The End Game”. It envisioned a revolt by INC-led Shi’ites in southern Iraq and Kurds in the north that would inspire a military uprising and lead to the installation of an INC-dominated regime friendly to the U.S. He also began to use some of his CIA funding to build an armed militia. A later variation also included the presence of ex-U.S. Special Forces to incite Iraqi military defections. The U.S. would then recognize the INC as Iraq’s provisional government, give it Iraq’s U.N. seat; create INC-controlled "liberated zones" freed of sanctions, give the INC frozen Iraqi assets under U.S. control, launch air attacks, and have equipment prepositioned in the region in case U.S. ground forces were activated. The plan was quietly championed by neoconservatives before and during the early months of the Bush administration.[126][127][128][129]

Differences within INC eventually led to its virtual collapse. In May 1994, the two main Kurdish parties began fighting with each other over territory and other issues. In January 1995, CIA case officer Robert Baer traveled to northern Iraq with a five-man team to set up a CIA station. He made contact with the Kurdish leadership and managed to negotiate a truce between Barzani and Talabani.[130]

Within days, Baer and the INC made contact with an Iraqi general who was plotting to assassinate Saddam Hussein. The plan was to use a unit of 100 renegade Iraqi troops to kill Saddam as he passed over a bridge near Tikrit. Chalabi was convinced, as the commanders to whom they had spoken, were the same who openly supported Saddam and crushed his opponents in the Kurdish and Shia revolts. Baer cabled the plan to Washington but did not hear anything back. After three weeks, the plan was revised, calling for an attack by Kurdish forces in northern Iraq while rebel Iraqi troops leveled one of Saddam's houses with tank fire in order to kill the Iraqi leader. Baer again cabled the plan to Washington and received no response. On 28 February, the Iraqi Army was placed on full alert. In response, the Iranian and Turkish militaries were also placed on high alert. Turkey had been planning to launch on offensive against Kurdish rebels in northern Iraq. Baer received a message directly from National Security Advisor Tony Lake telling him his operation was compromised. This warning was passed on Baer's Kurdish and Iraqi contacts. Upon learning this, Barzani backed out of the planned offensive, leaving Talabani's PUK forces to carry it out alone. The Iraqi Army officers planning to kill Saddam with tank fire were compromised, arrested and executed before they could carry out the operation. The PUK's offensive was still launched as planned, and within days they managed to destroy three Iraqi Army divisions and capture 5,000 prisoners.[130] Despite Baer's pleas for American support of the offensive, none was forthcoming, and the Kurdish troops were forced to withdraw.[130] The failure of the 1995 coup attempt lead to the command structure of INC to fall apart with factional infighting. Chalabi was banned from those frequent visits to CIA headquarters at Langley, Virginia.

In the summer of 1996, fighting resumed between the Kurdish parties. The KDP subsequently garnered armed support from Saddam Hussein in 1996 for its capture of the town of Arbil from rival PUK. Iraq took advantage of the request by launching a military strike in which 200 opposition members were executed and as many as 2,000 arrested. 650 oppositionists (mostly INC) were evacuated and resettled in the United States under parole authority of the US Attorney General.[131]

INC was subsequently plagued by factional infighting, a cutoff of funds from its international backers (including the United States), and continued pressure from Iraqi intelligence services especially after the failed 1995 coup attempt. In 1998, however, the US Congress authorized $97 million in U.S. military aid for Iraqi opposition via the Iraq Liberation Act, intended primarily for INC.[131]

Another opposition group was the Iraqi National Accord. Unlike the Iraqi National Congress strategy of fomenting revolution among Iraq's disaffected minorities, the INA felt the best way to remove Saddam was organizing a coup among Iraqi military and security services. From 1992-1995, INA insurgents conducted a bomb and sabotage campaign.[132] However, the INA had been infiltrated by agents loyal to Saddam, and in June 1996, 30 Iraqi military officers were executed and 100 others were arrested for alleged ties to the INA.[133]

In October 1998, removing the Iraqi government became official U.S. foreign policy with enactment of the Iraq Liberation Act. Enacted following the expulsion of UN weapons inspectors the preceding August (after some had been accused of spying for the U.S.), the act provided $97 million for Iraqi "democratic opposition organizations" to "establish a program to support a transition to democracy in Iraq."[134]

Neoconservatives and Iraq

[edit]As containment eroded, hawks began advocating a more aggressive approach to confronting Iraq. Known as neoconservatives, they were grounded on the view of "peace through strength", that military power and strength should be used to confront American adversaries and threats, as well as unilaterally promoting American interests such as fostering democratization globally.[135] Many harbored a distrust towards the intelligence community for underestimating threats to the United States and preferred utilizing outside analysis to separately review intelligence data. During the 1970s, many accused the CIA of underestimating the Soviet Union's military strength and intentions. After lobbying, the White House and the CIA agreed to an experiment of outside analysis on Soviet military power, which became known as Team B.[136] Headed by a team of 16 "outside experts" who had access to highly classified data, they argued that the USSR was engaged in a military buildup utilizing the doctrine of winning nuclear wars, rather than the CIA's view that the USSR was reliant on mutually assured destruction.[136][137][138] The study's finding later helped influence the American military buildup during the Reagan administration.[139] During the Reagan administration, many neoconservatives took up roles in the administration and staunchly supported the Reagan Doctrine against global Communism.

Many viewed George H.W. Bush's decision to leave Saddam Hussein in power after the Gulf War and allowing him to crush the 1991 uprisings as a betrayal of democratic principles.[140][141][142][143][144][76] After the end of both the Gulf War and the Cold War, neoconservative Paul Wolfowitz as Under Secretary of Defense for Policy worked on a draft Defense Planning Guidance that called for American unilateralism and reliance on preemption to strike emerging threats before they materialized. The draft outlines several scenarios in which U.S. interests could be threatened by regional conflict: "access to vital raw materials, primarily Persian Gulf oil; proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and ballistic missiles, threats to U.S. citizens from terrorism or regional or local conflict, and threats to U.S. society from narcotics trafficking." The draft relies on seven scenarios in potential trouble spots to make its argument—with the primary case studies being Iraq and North Korea. Although the document was never formally adopted by the Bush Sr. administration, elements later appeared as part of the Bush Jr. administration and doctrine.[76] In 1996, a study group of American-Jewish neoconservative strategists led by Richard Perle drafted a foreign policy report on the behest of newly-elected Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Known as the A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm, the report called for a new, more aggressive Middle East policy on the part of the United States in defense of the interests of Israel, including the removal of Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq and the containment of Syria through a series of proxy wars, the outright rejection of any solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that would include a Palestinian state, and an alliance between Israel, Turkey and Jordan against Iraq, Syria and Iran.[145]

Project for the New American Century

[edit]Founded by William Kristol and Robert Kagan, the Project for the New American Century (PNAC) was a neoconservative think tank that called for "a Reaganite policy of military strength and moral clarity".[146][147][148][149] PNAC's first public act was to release a June 1997 "Statement of Principles" that described the United States as the "world's pre-eminent power", and said that the nation faced a challenge to "shape a new century favorable to American principles and interests". To this goal, the statement called for significant increases in defense spending, and for the promotion of "political and economic freedom abroad". It said the United States should strengthen ties with its democratic allies, "challenge regimes hostile to our interests and values", and preserve and extend "an international order friendly to our security, our prosperity, and our principles". Calling for a "Reaganite" policy of "military strength and moral clarity", it concluded that PNAC's principles were necessary "if the United States is to build on the successes of this past century and to ensure our security and our greatness in the next".[150] Of the twenty-five people who signed PNAC's founding statement of principles, ten went on to serve in the administration of U.S. President George W. Bush, including Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and Paul Wolfowitz.[151][152][153][154]

In 1998, Kristol and Kagan advocated regime change in Iraq throughout the Iraq disarmament process through articles that were published in the New York Times.[155][156] Following perceived Iraqi unwillingness to co-operate with UN weapons inspections, core members of the PNAC including Richard Perle, Paul Wolfowitz, R. James Woolsey, Elliott Abrams, Donald Rumsfeld, Robert Zoellick, and John Bolton were among the signatories of an open letter initiated by the PNAC to President Bill Clinton calling for the removal of Saddam Hussein.[157][158] Portraying Saddam Hussein as a threat to the United States, its Middle East allies, and oil resources in the region, and emphasizing the potential danger of any weapons of mass destruction under Iraq's control, the letter asserted that the United States could "no longer depend on our partners in the Gulf War to continue to uphold the sanctions or to punish Saddam when he blocks or evades UN inspections". Stating that American policy "cannot continue to be crippled by a misguided insistence on unanimity in the UN Security Council", the letter's signatories asserted that "the U.S. has the authority under existing UN resolutions to take the necessary steps, including military steps, to protect our vital interests in the Gulf".[159]

Neoconservatives and PNAC formed close political relationships with Ahmed Chalabi's Iraqi National Congress, who was championed as a notable force for democracy in Iraq.[160] They lobbied for the Iraq Liberation Act, which declared that it was the official policy of the United States to support "regime change", and required the President to assist Iraqi opposition groups including the INC. The law was signed by President Clinton in October 1998.[161][162][163]

Rumsfeld Commission

[edit]Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, proponents of a missile defense shield began to focus on the risk posed by rogue states developing ballistic missiles capable of eventually reaching the US.[164] Although the 1995 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE), stated that there was no state besides the five major nuclear powers was capable of acquiring missiles that could reach the United States within the ensuing 15 years, Republican lawmakers intent on funding a defensive shield accused the Clinton administration for inaccurate assessments and distorted intelligence.[164][165] In early 1996, the House National Security Committee held hearings on the ballistic missile threat, and in a final report recommended that two reviews be created: one to investigate the NIE itself, and another to complete a new investigation of the ballistic missile threat.[166] The first review was conducted by former Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) and future Defense Secretary Robert Gates. He concluded that while there was evidence of faulty methodology in the NIE, there was no political bias in its conclusions.[167] This conclusion again angered the missile defense supporters who had counted on this review to further their arguments.[165]

The second review was headed by a commission chaired by once and future Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld in early 1998.[168] During that time the commission were frustrated by the compartmentalization of intelligence, the refusal of analysts to speculate or hypothesize on given information, and what they considered general inexperience in the intelligence personnel.[169][170] The final report argued that the US was threatened by ballistic missiles tipped with biological or nuclear payloads from China, Russia, Iran, Iraq, and North Korea. The report criticized the U.S. intelligence community for underestimating these growing threats and that the processes of the intelligence community to make estimates on these threats were causing an erosion of accurate assessments.[171] The commission is thought by some foreign policy analysts to be the basis for President George W. Bush's axis of evil line in his 2002 State of the Union Address, in which he accused Iraq, Iran, and North Korea of being state sponsors of terrorism and of pursuing weapons of mass destruction.[172] The Rumsfeld Commission grouped the three countries together because they all were believed to be pursuing ballistic missile programs based on the Scud missile. In the pre-9/11 days of the Bush presidency, the administration had focused heavily on developing a national missile defense system to counter such threats.[173]

Bush administration (Pre-9/11)

[edit]The Republican Party's campaign platform in the 2000 election called for "full implementation" of the Iraq Liberation Act as "a starting point" in a plan to "remove" Saddam.[174] Following the 2000 election, Clinton briefed President-elect George W. Bush in December 2000, expressing his regret that people he regarded as the world's two most dangerous individuals, Osama Bin Laden and Saddam Hussein, were still alive and free. Of the latter, he warned Bush that Hussein will "cause you a world of problems."[175] Upon his inauguration, Bush directed the Pentagon to look into military options for Iraq and the CIA to improve intelligence on the country.[176][177] At a February 1 principals meeting Paul Wolfowitz lobbied for arming the Iraqi opposition.[177] Bush's Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill also claimed that Bush's first two National Security Council meetings included a discussion of invading Iraq. He was given briefing materials entitled "Plan for post-Saddam Iraq," which envisioned peacekeeping troops, war crimes tribunals, and divvying up Iraq's oil wealth. A Pentagon document dated March 5, 2001 was titled "Foreign Suitors for Iraqi Oilfield contracts," and included a map of potential areas for exploration.[178] A contingency plan known as Operation Desert Badger was also created if Iraq successfully shot down a U.S. warplane in the no-fly zones. The plan called for major attacks on the Iraqi regime, which would have exceeded Operation Desert Fox in scope and scale. It also included the option of utilizing ground troops stationed in Kuwait to seize territory in Southern Iraq.[179]

September 11 attacks and immediate response

[edit]These old dinosaurs of U.S. foreign policy, were stuck in a time warp. They're not mentally flexible enough to understand the world has changed since they were in office. They were thinking about the Cold War, where states were the source of threat. They dismissed these non-state actors, these shadowy groups. That was one of the flaws in W's thinking. That bringing old veterans in would be useful in a time of change. It wasn't. It was the opposite.

— Timothy Naftali, American Experience

On the morning of 11 September 2001, a total of 19 Arab men—15 of whom were from Saudi Arabia—carried out four coordinated attacks in the United States. Four commercial passenger jet airliners were hijacked.[180][181] The hijackers intentionally crashed two of the airliners into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, killing everyone on board and more than 2,000 people in the buildings. Both buildings collapsed within two hours from damage related to the crashes, destroying nearby buildings and damaging others. The hijackers crashed a third airliner into the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C. The fourth plane crashed into a field near Shanksville, in rural Pennsylvania, after some of its passengers and flight crew attempted to retake control of the plane, which the hijackers had redirected toward Washington, D.C., to target the White House, or the US Capitol. No one aboard the flights survived. The death toll among responders including firefighters and police was 836 as of 2009.[182] Total deaths were 2,996, including the 19 hijackers.[182]

By midday, the National Security Agency intercepted communications that pointed to Osama Bin Laden's responsibility, and many members within the Central Intelligence Agency immediately knew that al-Qaeda had orchestrated the attacks.[183][184] However, elements within the Bush administration believed that an attack of such magnitude and complexity required a state actor.[184][185] On the evening of 11 September, President Bush stated the US would respond to the attacks and would "make no distinction between those who planned these acts and those who harbor them."[186]

Iraq was the only country in the world to praise the 9/11 attacks, issuing an official statement saying "the American cowboys are reaping the fruit of their crimes against humanity", while the official al-Iraq newspaper called the event "a lesson for all tyrants, oppressors and criminals."[187][188] The Duelfer Report later concluded that the reaction stemmed from Saddam's paranoia and misreading of international events, and that elements within the Iraqi government was fearful of how the U.S. would react and wanted to communicate that Iraq wasn't involved.[189]

Attempts to link Iraq to al-Qaeda

[edit]On the afternoon of September 11, Rumsfeld issued rapid orders to his aides to look for evidence of possible Iraqi involvement in regard to what had just occurred, according to notes taken by senior policy official Stephen Cambone. "Best info fast. Judge whether good enough hit S.H." – meaning Saddam Hussein – "at same time. Not only UBL" (Osama bin Laden), Cambone's notes quoted Rumsfeld as saying. "Need to move swiftly – Near term target needs – go massive – sweep it all up. Things related and not."[190][191] According to the 9/11 Commission Report, "Rumsfeld later explained that at the time, he had been considering either one of them, or perhaps someone else, as the responsible party."[185]

In the first emergency meeting of the National Security Council on the day of the attacks, Rumsfeld asked, "Why shouldn't we go against Iraq, not just al-Qaeda?" with his deputy Paul Wolfowitz adding that Iraq was a "brittle, oppressive regime that might break easily—it was doable," and, according to John Kampfner, "from that moment on, he and Wolfowitz used every available opportunity to press the case."[192] The idea was initially rejected at the behest of Secretary of State Colin Powell, but, according to Kampfner, "Undeterred Rumsfeld and Wolfowitz held secret meetings about opening up a second front—against Saddam. Powell was excluded." In such meetings they created a policy that would later be dubbed the Bush Doctrine, centering on "pre-emption" and the war on Iraq, which the PNAC had advocated in their earlier letters.[193]

On the evening of 12 September, President Bush ordered White House counter-terrorism coordinator Richard A. Clarke to investigate possible Iraqi involvement in the 9/11 attacks. Shocked by the sophistication of the 9/11 attacks, Bush wondered whether a state sponsor was involved. He wondered whether Iraq was involved as it was an American adversary and was the only place where the United States was engaged in combat operations. He also recalled that Iraq had supported Palestinian suicide terrorists, and also thought whether Iran was involved as well. Clarke's office issued a memo on 18 September that noted wide ideological gaps between Iraq to al-Qaeda, and that only weak anecdotal evidence linked the two. The report found nothing of significance to indicate Iraqi involvement.[185]: 334 Clarke later recalled that the paper was quickly returned by a deputy with a note saying, "Please update and resubmit."[176][194] Similarly, a 21 September President's Daily Brief (prepared at Bush's request) indicated that the U.S. intelligence community had no evidence linking Saddam Hussein to the attacks and there was "scant credible evidence that Iraq had any significant collaborative ties with Al Qaeda." The PDB wrote off the few contacts that existed between Saddam's government and al-Qaeda as attempts to monitor the group, not work with it. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, Secretaries Colin Powell and Rumsfeld, under secretaries at the State and Defense Departments, and other senior administration officials received the paper.[195]

Clarke later revealed details of another National Security Council meeting the day after the attacks, during which officials considered the U.S. response. Already, he said, they were certain al-Qa'ida was to blame and there was no hint of Iraqi involvement. "Rumsfeld was saying we needed to bomb Iraq," according to Clarke. Clarke then stated, "We all said, 'No, no, al-Qa'ida is in Afghanistan.'" Clarke also revealed that Rumsfeld complained in the meeting, "there aren't any good targets in Afghanistan and there are lots of good targets in Iraq."[196] Rumsfeld even suggested to attack other countries like Libya and Sudan, arguing that if this was to be a truly "global war on terror" then all state sponsors of terrorism should be dealt with.[197]

Wolfowitz argued for action against Iraq, noting that Saddam had praised the attacks and claimed that Iraq was involved in the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center. A Pentagon paper specified three priority targets for initial action; al Qaeda, the Taliban, and Ba'athist Iraq. It argued that al Qaeda and Iraq posed a strategic threat to the United States with the latter being cited in being involved in sponsoring terrorism, along with its interest in weapons of mass destruction. Although Bush decided to prioritize the invasion of Afghanistan, he ordered contingency plans to be prepared for Iraq, which involved seizing Iraqi oilfields in the south.[185]

2001 anthrax attacks

[edit]Shortly after the 9/11 attacks, letters containing anthrax spores were mailed to several news media offices and to senators Tom Daschle and Patrick Leahy, killing five people and infecting 17 others. Capitol Police Officers and staffers working for Senator Russ Feingold were exposed as well.[198] The anthrax was determined to be weapons-grade. Later investigations showed that a domestic perpetrator had orchestrated the attacks.[199] But immediately after the anthrax attacks, White House officials pressured FBI Director Robert Mueller to publicly blame al-Qaeda following the September 11 attacks.[200] "They really wanted to blame somebody in the Middle East," the retired senior FBI official stated. The FBI knew early on that the anthrax used was of a consistency requiring sophisticated equipment and was unlikely to have been produced in "some cave". At the same time, President Bush and Vice President Cheney in public statements speculated about the possibility of a link between the anthrax attacks and al-Qaeda.[201] The Guardian reported in early October that American scientists had implicated Iraq as the source of the anthrax,[202] and the next day The Wall Street Journal editorialized that al-Qaeda perpetrated the mailings, with Iraq the source of the anthrax.[203] A few days later, John McCain suggested on the Late Show with David Letterman that the anthrax may have come from Iraq,[204] and the next week ABC News did a series of reports stating that three or four (depending on the report) sources had identified bentonite as an ingredient in the anthrax preparations, implicating Iraq.[205][206][207]

Distrust of intelligence community

[edit]"This is the same crowd that worked with the mujahideen in Bosnia, that couldn't give us any heads up on the worst intelligence failure in U.S. history? And they're going to criticize me? It's pathetic."

Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, as well as other neoconservatives sought out information that linked both Ba'athist Iraq and al-Qaeda together, and expressed skepticism toward's the CIA's intelligence. They questioned whether the CIA were competent enough to produce accurate information as the agency underestimated threats and failed to accurately predict events such as the Iranian Revolution, the Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait, and the collapse of the Soviet Union. In addition following the Gulf War, UNSCOM inspections revealed the presence of an intact Iraqi military facility that had facilitated the development of a nuclear weapon that was mere months away from its first nuclear weapons detonation. The CIA had no knowledge of such a facility beforehand.[184]

"No one in my office ever claimed there was an operational relationship. There was a relationship."[208]

They instead preferred outside analysis, of which information was supplied by the Iraqi National Congress as well as unvetted pieces of intelligence.[184] According to John Kampfner, "Rumsfeld and Wolfowitz believed that, while the established security services had a role, they were too bureaucratic and too traditional in their thinking." As a result, "they set up what came to be known as the 'cabal', a cell of eight or nine analysts in a new Office of Special Plans (OSP) based in the U.S. Defense Department." The office was headed by Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Douglas Feith. According to an unnamed Pentagon source quoted by Hersh, the OSP "was created in order to find evidence of what Wolfowitz and his boss, Defense Secretary Rumsfeld, believed to be true—that Saddam Hussein had close ties to Al Qaeda, and that Iraq had an enormous arsenal of chemical, biological, and possibly even nuclear weapons that threatened the region and, potentially, the United States".[193] Within months of being set up, the OSP "rivaled both the CIA and the Pentagon's Defense Intelligence Agency, the DIA, as President Bush's main source of intelligence regarding Iraq's possible possession of weapons of mass destruction and connection with Al Qaeda."

"You're wrong. You know you're wrong. Go back and find out. Look at the rest of the reports and find out that you're wrong."

The INC provided information that argued that Iraq had ties to al-Qaeda. In addition, the OSP reviewed raw intelligence. One information claimed that lead 9/11 hijacker Mohammed Atta had met with Iraqi intelligence in Prague, Czech Republic in April 2001. Another included information about a captured al-Qaeda militant Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi. al-Libi claimed that al-Qaeda had sought weapons of mass destruction from Iraq.[184] However, these pieces of information had been already discredited by the intelligence community.[209][210] Despite this, they continued to work alleging a Saddam-al-Qaeda connection. In one instance, an "Iraqi intelligence cell" briefing to Rumsfeld and Wolfowitz in August 2002 condemned the CIA's intelligence assessment techniques and denounced the CIA's "consistent underestimation" of matters dealing with the alleged Iraq–Al-Qaeda co-operation. In September 2002, two days before the CIA's final assessment of the Iraq-al Qaeda relationship, Feith briefed senior advisers to Dick Cheney and Condoleezza Rice, undercutting the CIA's credibility and alleging "fundamental problems" with CIA intelligence-gathering.

“It was something like a spy novel. It was a room where people were scanning Iraqi intelligence documents into computers, and doing disinformation. There was a whole wing of it that he did forgeries in.”

Critics heavily denounced the role of the OSP for their role in the Iraq War. In an interview with the Scottish Sunday Herald, former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officer Larry C. Johnson said the OSP was "dangerous for US national security and a threat to world peace. [The OSP] lied and manipulated intelligence to further its agenda of removing Saddam. It's a group of ideologues with pre-determined notions of truth and reality. They take bits of intelligence to support their agenda and ignore anything contrary. They should be eliminated."[211] In an interview, Vincent Cannistraro, a former senior CIA official and counterterrorism expert stated that the intelligence provided by the Iraqi National Congress "... isn't reliable at all. Much of it is propaganda. Much of it is telling the Defense Department what they want to hear. And much of it is used to support Chalabi's own presidential ambitions. They make no distinction between intelligence and propaganda, using alleged informants and defectors who say what Chalabi wants them to say, [creating] cooked information that goes right into presidential and vice-presidential speeches."[212] The actions of the OSP have led to accusation of the Bush administration "fixing intelligence to support policy" with the aim of influencing Congress in its use of the War Powers Act.[213]

Congressional assessment of the need for war

[edit]Senator Bob Graham chaired the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in 2002, when the Congress voted on the Iraq War Resolution. He first became aware of the significance of Iraq in February 2002, when Gen. Tommy Franks told him the Bush administration had made the decision to begin to de-emphasize Afghanistan in order to get ready for Iraq. In September, the Senate Intelligence Committee met with George Tenet, Director of the CIA, and Graham requested a National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) on Iraq. Tenet responded by saying "We've never done a National Intelligence Estimate on Iraq, including its weapons of mass destruction." and resisted the request to provide one to Congress. Graham insisted "This is the most important decision that we as members of Congress and that the people of America are likely to make in the foreseeable future. We want to have the best understanding of what it is we're about to get involved with." Tenet refused to do a report on the military or occupation phase, but reluctantly agreed to do a NIE on the weapons of mass destruction. Graham described the Senate Intelligence Committee meeting with Tenet as "the turning point in our attitude towards Tenet and our understanding of how the intelligence community has become so submissive to the desires of the administration. The administration wasn't using intelligence to inform their judgment; they were using intelligence as part of a public relations campaign to justify their judgment."[214]

Congress voted to support the war based on the NIE Tenet provided in October 2002. However, the bipartisan "Senate Intelligence Committee Report on Prewar Intelligence" released on July 7, 2004, concluded that the key findings in the 2002 NIE either overstated, or were not supported by, the actual intelligence. The Senate report also found the US Intelligence Community to suffer from a "broken corporate culture and poor management" that resulted in a NIE that was completely wrong in almost every respect.[215]

See also

[edit]- Outline of the Iraq War

- International reactions to the prelude to the Iraq War

- Oil-for-Food Programme

- Operation Northern Watch

- Prelude to the Russian invasion of Ukraine

References

[edit]- ^ "Republican Platform 2000". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 April 2006. Retrieved 25 May 2006.

- ^ "Text of U.N. resolution on Iraq - Nov. 8, 2002". CNN.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ United Nations Security Council PV 4701. page 2. Colin Powell United States 5 February 2003. Retrieved accessdate.

- ^ Bellinger, John. "Transatlantic Approaches to the International Legal Regime in an Age of Globalization and Terrorism". US State Department. Retrieved 2017-06-24.

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine (1991). The Outlaw State: Saddam Hussein's Quest for Power and the Gulf Crisis. John Wiley & Sons. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-471-54299-5.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 185.

- ^ Karsh, Efraim The Iran–Iraq War 1980–1988, London: Osprey, 2002 pp. 7–8

- ^ Bulloch, John and Morris, Harvey The Gulf War, London: Methuen, 1989 p. 37.

- ^ Karsh, Efraim The Iran–Iraq War 1980–1988, London: Osprey, 2002 p. 8

- ^ a b Milani, Abbas. The Shah, London: Macmillan, 2011, p. 360.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 140, 144–145, 148, 181.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 205.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 146–148.

- ^ "Memorandum From the President's Deputy Assistant for National Security Affairs (Haig) to the President's Assistant for National Security Affairs (Kissinger), Washington, July 28, 1972: Kurdish Problem". Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–4, Documents on Iran and Iraq, 1969–1972. 1972-07-28. Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ^ "Iran – State and Society, 1964–74". Country-data.com. 21 January 1965. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2011.