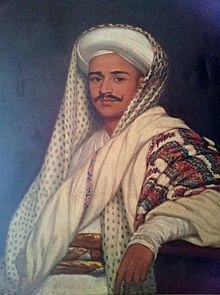

Rana Jang Pande

Shree Mukhtiyar Kaji Saheb Rana Jung Pande | |

|---|---|

| श्री मुख्तियार काजी साहेब रणजङ्ग पाँडे | |

| |

| Third Mukhtiyar of Nepal | |

| In office 1837 A.D – 1837 A.D | |

| Preceded by | Bhimsen Thapa |

| Succeeded by | Ranganath Poudyal |

| In office 1839 A.D – 1840 A.D | |

| Preceded by | Chautariya Pushkar Shah |

| Succeeded by | Ranganath Poudyal |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1789 A.D Kathmandu |

| Died | 18 April 1843 A.D Kathmandu |

| Citizenship | Nepal |

| Nationality | Nepali |

| Children | Badarjung, Tekjung, Samarjung, Shumsherjung |

| Parent | Damodar Pande |

Rana Jang Pande (Nepali: रणजङ्ग पाँडे) was the 3rd Prime Minister of the government of Nepal and the most powerful person in political scenario in three decades from the aristocratic Pande clan. He was one of the sons of Mukhtiyar Kaji Damodar Pande.[1][2] He served as the Prime Minister for two terms, serving 1837–1837 (First Term) and 1839–1840 AD (Second Term). He became powerful after Bhimsen Thapa was arrested, and was declared Mukhtiyar and Commander in Chief. He was a grandson of Kaji Kalu Pandey who was the commander of King Prithvi Narayan Shah and the Mulkaji of Gorkha and a notable figure during the unification campaign of Nepal.

The death of Queen Tripurasundari in 1832, who was a distant cousin of Rana Jang and the strongest supporter and niece of Bhimsen Thapa, and the adulthood of King Rajendra, weakened Bhimsen Thapa's hold on power. The conspiracies and infighting with rival courtiers (especially the Pandes, who held Bhimsen Thapa responsible for the death of Damodar Pande in 1804) finally led to imprisonment of Bhimsen Thapa and death by suicide in 1839. However, the court infighting did not subside with his death, and the political instability eventually paved way for the establishment of the Rana dynasty.

Rise to Power

[edit]Rana Jang Pande was stationed as a captain in the army in Kathmandu. He was aware of the disunity between the Samrajya Laxmi and Bhimsen, and thus he had secretly expressed his loyalty to Samrajya Laxmi and had vowed to help her in bringing Bhimsen Thapa down for all the wrongs he had committed against his family.[3] Factions in the Nepalese court had also started to develop around the rivalry between the two queens, with the senior queen supporting the Pandes, while the junior queen supporting the Thapas.[4] About a month after Mathabar's return to Kathmandu, a child was born out of an adulterous relationship between him and his widowed sister-in-law. This news was spread all over the country by the Pandes, and the resulting public disgrace forced Mathabar to leave Kathmandu and reside in his ancestral home in Pipal Thok, Borlang, Gorkha.[3] To save face, Bhimsen gave Mathabar the governorship of Gorkha.[3]

Taking advantage of Mathabar's absence in Kathmandu, the military battalions under his command were distributed to other courtiers during the annual muster at the beginning of 1837.[5] Nevertheless, Bhimsen managed to secure his and his family members' positions in the civil and military offices. An investigation was also started to check Bhimsen's expenditures in establishing various battalions.[5] Such events led the courtiers to feel that Bhimsen's Mukhtiyari (prime ministership) would not last very long; thus Ranabir Singh Thapa, in the hopes of becoming the next Mukhtiyar (Prime Minister), wrote a letter to the King asking him to be recalled to Kathmandu from Palpa. His wish was granted; and Bhimsen, pleased to see his brother after many years, made Ranbir Singh the acting Mukhtiyar and decided to go to his ancestral home in Borlang Gorkha for the sake of pilgrimage.[6] But in truth, Bhimsen had gone to Gorkha to placate his nephew and bring him back to Kathmandu.[6]

In Bhimsen's absence, Rajendra established a new battalion, Hanuman Dal, to be kept under his personal command. By February 1837, both Ranjang Pande and his brother, Ranadal Pande, had been promoted to the position of a Kaji; and Ranjang was made a personal secretary to the King, while Ranadal was made the governor of Palpa.[7] Ranjang was also made the chief palace guard, the position formerly occupied by Ranbir Singh and then Bhimsen. Thus, this curtailed Bhimsen's access to the royal family.[7] On 14 June 1837, the King took over the command of all the battalions put in charge to various courtiers, and himself became the Commander-in-Chief.[8][9]

Mission to China

[edit]In December 1835, the political rival of Prime Minister Bhimsen Thapa had requested Chinese Amban's in Lhasa to request King Rajendra Bikram Shah to send Kaji Rana Jang Pande as the leader of the 10th quinquennial mission to China.[10] As a result, the Chinese Amban wrote to the Nepalese King to personally nominate the leader of the next five-year mission to Peking. The Chinese Amban strongly suggested that Rana Jang Pande be appointed leader of the mission. King Rajendra Bikram Shah nominated Chautariya Pushkar Shah instead of Rana Jang Pande.[11] One source however states that the Chinese Amban had also suggested King Rajendra not to send wicked Rana Jang Pande, but to nominate another good, virtuous person to lead the quinquennial mission to the Ching Emperor's Court.[12] Despite this, Jagat Bam Pande was originally supposed to lead the 1837 mission.[13] After Chautariya Pushkar Shah left for Peking there was a big political upheaval in Nepal with the dismissal and imprisonment of the Prime Minister Bhimsen Thapa. Bhimsen Thapa held the post of Prime Minister continuously for thirty one years. The Nepalese court informed the Chautariya about the political developments in Nepal and dispatched him a letter to hand over to the Ching Emperor. Due to the political turmoil in Nepal, the Chautariya tried to complete his mission and return to Nepal as early as possible. He completed the round-trip journey to Peking in less than fourteen months. The mission of 1837 recorded a detailed and systematic summary of the routes from Kathmandu to Peking as traveled by the Nepalese envoy to Peking.[14]

Hold on power

[edit]

Immediately after the incarceration of the Thapas, a new government with joint Mukhtiyars was formed with Ranga Nath Poudyal as the head of civil administration, and Dalbhanjan Pande and Rana Jang Pande as joint heads of military administration.[15] This appointment established the Pandes as the dominant faction in the court, and they started to make preparations for war with the British in order to win back the lost territories of Kumaon and Garhwal.[16] While such war posturing was nothing new, the din the Pandes created alarmed not just the Resident Hodgson[16] but the opposing court factions as well, who saw their aggressive policy as detrimental to the survival of the country.[17] After about three months in power, under pressure from the opposing factions, the King removed Ranajang as Mukhtiyar and Ranga Nath Poudyal, who was favorably inclined towards the Thapas, was chosen as the sole Mukhtiyar.[18][19][20][17]

Fearful that the Pandes would re-establish their power, Fateh Jung Shah, Ranga Nath Poudyal, and the Junior Queen Rajya Laxmi Devi obtained from the King the liberation of Bhimsen, Mathabar, and the rest of the party, about eight months after they were incarcerated for the poisoning case.[19][20][21] Some of their confiscated land as well as the Bagh Durbar was also returned. Upon his release, the soldiers loyal to Bhimsen crowded behind him in jubilation and followed him up to his house; a similar treatment was given to Mathabarsingh Thapa and Sherjung Thapa.[17] Although pardon had been granted to Bhimsen, his former office was not re-instated; thus he went to live in retirement at his patrimony in Borlang, Gorkha.[20][21]

However, Ranga Nath Poudyal, finding himself unsupported by the King, resigned from the Mukhtiyari, which was then conferred on Pushkar Shah; but Puskhar Shah was only a nominal head, and the actual authority was bestowed on Ranjang Pande.[22] Sensing that a catastrophe was going to befall the Thapas, Mathabar Singh Thapa fled to India while pretending to go on a hunting trip; Ranbir Singh Thapa gave up all his property and became a sanyasi, titling himself Swami Abhayananda; but Bhimsen Thapa preferred to remain in his old home in Gorkha.[21][23] The Pandes were now in full possession of power; they had gained over the King to their side by flattery. The senior queen had been a firm supporter of their party; and they endeavored to secure popularity in the army by promises of war and plunder.[22]

Decline from power

[edit]

Mathabarsingh Thapa, who was exiled to India when Bhimsen Thapa was supposedly found to be guilty of murdering the King Rajendra's son who was 6 months old, was asked to return to Nepal by the queen. Mathabarsingh Thapa arrived in Kathmandu Valley in 1843 April 17 where a great welcome was organized for him.[24] After consolidating his position, he successfully led to the murder of all his political adversaries Karbir Pande, Kulraj Pande, Ranadal Pande, Indrabir Thapa, Ranabam Thapa, Kanak Singh Basnet, Gurulal Adhikari and many others, in several pretexts.[25] The second queen of Rajendra, Queen Rajya Laxmi declared him Minister and Commander-In-Chief of the Nepalese army in 1843 December 25 believing he would help to usurp the power from Rajendra, her own husband, and make her own son, Ranendra as the king of Nepal.[citation needed]

Death

[edit]Rana Jang Pandey was forced to see the murdered dead bodies of his brothers and nephews on April 18, 1843. Rana Jang lying ill in his bed was not given death sentence. Rana Jang was shocked to death after seeing the dead bodies of his brothers and nephews on 18 April 1843.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ "Internal Server Error 500". sanjaal.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Prime Ministers of Nepal". We All Nepali. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Acharya 2012, p. 155.

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 108.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 156.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 157.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 158.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 215.

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 105.

- ^ Chitta Ranjan Nepali, General Bhimsen Thapa Ra Tatkalin Nepal, Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, Third Edition, 2035 B.S., pp 206-207

- ^ Ludwig F. Stiller, The Silent Cry, Kathmandu: Sahayogi Prakashan, 1976, p 23

- ^ Chinese Amban to King Rajendra, Tao Kwang 16th Year (1839 B.S., Magha 21, MFA, Pako No Pa. 64

- ^ Bhim Bahadur Pande Chhetri, Rastra Bhakti Ko Jhalak:Pande Bamsa Ko Bhumika, 1596-1904 B.S., kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, 2034 B.S, P. 156

- ^ B.H. Hodgson, "Route of Two Nepalese Embassies to Peking with Remarks on the watershed and plateau of Tibet", Journal of Asiatic Society, No VI, 1856, pp 486-490

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 106.

- ^ a b Pradhan 2012, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Pradhan 2012, p. 164.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 160.

- ^ a b Oldfield 1880, p. 311.

- ^ a b c Nepal 2007, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Acharya 2012, p. 161.

- ^ a b Oldfield 1880, p. 313.

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 110.

- ^ Sharma, Balchandra (c. 1976). Nepal ko Aitehasik Rooprekha. Varanasi: Krishna Kumari Devi. p. 295.

- ^ a b Acharya 1971, p. 17.

Bibliography

[edit]- Acharya, Baburam (1971), "The Fall of Bhimsen Thapa and The Rise of Jang Bahadur Rana" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 3, Kathmandu: 214–219

- Acharya, Baburam (2012), Acharya, Shri Krishna (ed.), Janaral Bhimsen Thapa : Yinko Utthan Tatha Pattan (in Nepali), Kathmandu: Education Book House, p. 228, ISBN 9789937241748

- Amatya, Shaphalya (June–November 1978), "The failure of Captain Knox's mission in Nepal" (PDF), Ancient Nepal (46–48), Kathmandu: 9–17, retrieved 11 January 2013

- Hunter, William Wilson (1896), Life of Brian Houghton Hodgson, London: John Murry

- Joshi, Bhuwan Lal; Rose, Leo E. (1966), Democratic Innovations in Nepal: A Case Study of Political Acculturation, University of California Press, p. 551

- Kandel, Devi Prasad (2011), Pre-Rana Administrative System, Chitwan: Siddhababa Offset Press, p. 95

- Karmacharya, Ganga (2005), Queens in Nepalese politics: an account of roles of Nepalese queens in state affairs, 1775–1846, Kathmandu: Educational Pub. House, p. 185, ISBN 9789994633937

- Nepal, Gyanmani (2007), Nepal ko Mahabharat (in Nepali) (3rd ed.), Kathmandu: Sajha, p. 314, ISBN 9789993325857

- Oldfield, Henry Ambrose (1880), Sketches from Nipal, Vol 1, vol. 1, London: W.H. Allan & Co.

- Pemble, John (2009), "Forgetting and remembering Britain's Gurkha War", Asian Affairs, 40 (3): 361–376, doi:10.1080/03068370903195154, S2CID 159606340

- Pradhan, Kumar L. (2012), Thapa Politics in Nepal: With Special Reference to Bhim Sen Thapa, 1806–1839, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, p. 278, ISBN 9788180698132