Rory Gallagher

Rory Gallagher | |

|---|---|

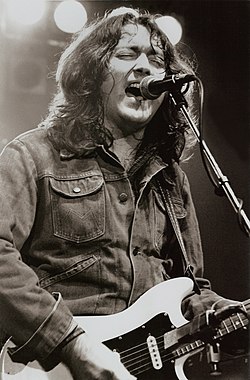

Gallagher performing at the Manchester Apollo in 1982 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | William Rory Gallagher |

| Born | 2 March 1948 Ballyshannon, County Donegal, Ireland |

| Origin | Cork, Ireland |

| Died | 14 June 1995 (aged 47) London, England |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1963–1995 |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | Taste |

| Website | rorygallagher |

William Rory Gallagher (/ɡæləhər/ GAL-ə-hər; 2 March 1948 – 14 June 1995)[1][2][3] was an Irish musician, singer, and songwriter. Regarded as "Ireland's first rock star",[4] he is known for his virtuosic style of guitar playing and live performances. He has sometimes been referred to as "the greatest guitarist you've never heard of".[5][6]

Gallagher gained international recognition in the late 1960s as the frontman and lead guitarist of the blues rock power trio Taste. Following the band's break-up in 1970, he launched a solo career and was voted Guitarist of the Year by Melody Maker magazine in 1972.[7] Gallagher played over 2,000 concerts worldwide throughout his career, including many in Northern Ireland during the Troubles.[8] He had global record sales exceeding 30 million.[9][10]

During the 1980s, Gallagher continued to tour and record new music, but his popularity declined due to shifting trends in the music industry.[11] His health also began to deteriorate, resulting in a liver transplant in March 1995 at King's College Hospital in London.[12] Following the operation, he contracted a staphylococcal infection (MRSA) and died three months later at the age of 47.[13]

Gallagher has been commemorated posthumously with statues in Ballyshannon and Belfast, and public spaces renamed in his memory in Dublin, Cork, and Paris.[14] He has been commemorated on an An Post set of postage stamps and a Central Bank of Ireland commemorative coin.[15][16] Since 2002, the Rory Gallagher International Tribute Festival has been held annually in Ballyshannon.[17]

A number of musicians in the world of rock and blues cite Gallagher as an influence, both for his musicianship and character, including Brian May (Queen),[18] Johnny Marr (The Smiths),[19] Slash (Guns N' Roses), The Edge (U2), Glenn Tipton (Judas Priest), Janick Gers (Iron Maiden), Vivian Campbell (Def Leppard), Joan Armatrading,[20] Gary Moore, and Joe Bonamassa.[21]

Early life

[edit]Gallagher was born on 2 March 1948 to Daniel (Danny) and Monica Gallagher (née Roche) at the Rock Hospital in Ballyshannon in County Donegal, Ireland.[22][23][8][24] He was baptised in the nearby St Joseph's Church.[25]

His father, Danny, was originally from Derry and served for a time in the Irish Army. Danny was also an accordionist and led his own céilí dance orchestra.[24] He met Gallagher’s mother, Monica – a native of County Cork – in the 1940s while stationed in Cork city, and they later married.[12]

The couple moved to Ballyshannon when Danny was demobilised and took up employment with the Irish Electricity Supply Board (ESB), which was constructing the Cathaleen's Fall hydroelectric power station on the River Erne.[26]

In 1949, the family moved to Derry City.[25] It was here that Gallagher's younger brother Dónal was born later that year.[23][27] Dónal would go on to manage Gallagher throughout most of his career.[28][29] While in Derry, Gallagher attended the Christian Brothers Primary School, known locally as the Brow of the Hill.[25]

Over the next seven years, due to a lack of steady work, the family moved frequently, spending time in Coventry and Birmingham in England, as well as moving back and forth between Cork and Derry.[30] This instability put a strain on Danny and Monica’s marriage, and in 1956, Monica moved back to Cork permanently with her two sons.[31] They lived with Gallagher's maternal grandparents in an apartment above the Modern Bar (later renamed Roche's Bar) at 27 MacCurtain Street.[31] Gallagher attended the North Monastery School and, later, St Kieran's College.[27][32]

Gallagher developed a love for music at a young age through the radio, listening to broadcasts from Radio Luxembourg, the BBC, and the American Forces Network.[33] His first musical inspiration was Roy Rogers, "the Singing Cowboy", followed by Lonnie Donegan, whose covers of American blues and folk artists introduced Gallagher to the genre.[34] He later discovered rock and roll, particularly Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, and Chuck Berry, before finding his greatest influence in Muddy Waters.[33] Other musicians he cited as influences include Woody Guthrie, Big Bill Broonzy, and Lead Belly.

At age nine, Gallagher received a plastic Elvis Presley model ukelele for Christmas,[27] on which he taught himself basic chords.[35] Recognising his aptitude, Gallagher’s mother later bought him an acoustic guitar. Gallagher would study music books in his local library, such as Lonnie Donegan’s Skiffle Hits, and copy the hand shapes of musicians from photographs in Melody Maker.[33]

Having acquired a repertoire of songs, Gallagher began performing at minor functions around Cork, often accompanied by his brother. In 1961, he won a cash prize as a solo performer in a talent contest at Cork City Hall, and his photo was featured in the Evening Echo.[31]

As Gallagher began performing more frequently, he sought to emulate the electric sound of beat groups. To achieve this, he persuaded his mother to buy him a black Rosetti Solid Seven electric guitar.[36]

The showband years

[edit]1963–1965 The Fontana Showband

[edit]Gallagher was eager to form a band but struggled to find anyone in Cork who shared his interest. In the summer of 1963, while searching through local newspapers, he came across an advertisement from brothers Oliver and Bernie Tobin, who were looking for a lead guitarist to join their newly-formed band, the Fontana Showband.[37]

The six-piece ensemble, which played the popular hits of the day,[38] featured Bernie Tobin on trombone, Oliver Tobin on bass, John Lehane on saxophone, Eamonn O'Sullivan on drums, and Jimmy Flynn on guitar. Gallagher impressed the band with his audition and lied about his age to secure the position. In the following weeks, Flynn left the band by mutual consent and Declan O’Keefe joined as rhythm guitarist.[25]

Shortly after joining the Fontana Showband, Gallagher purchased a 1961 Fender Stratocaster for £100 from Crowley's Music Shop.[39] This guitar became his primary instrument and was most associated with him during his career.[40]

The band performed in ballrooms and dancehalls across Ireland almost every evening, often for 5-6 hours at a time.[41] This allowed Gallagher to earn the money for the payments that were due on his Stratocaster guitar. During Lent, when dances were "banned" by the Catholic Church in Ireland, they toured Great Britain.[42]

Despite not playing the music he truly wanted, Gallagher saw the Fontana Showband as a valuable training ground.[41] Recognising the shifting musical landscape of the time, he gradually began to influence the band's repertoire, steering it away from mainstream pop music and incorporating some of Chuck Berry's songs. By 1965, he had successfully moulded Fontana into "The Impact", now with Michael Lehane on keyboards and Johnny Campbell on drums, replacing O’Sullivan.[37]

1965–1966 The Impact

[edit]On 22 April 1965, The Impact made an appearance on Irish television show Pickin’ the Pops, where they were scheduled to perform Buddy Holly’s 'Valley of Tears'. However, at the last minute, Gallagher switched the song to Larry Williams’ 'Slow Down' instead, an act that caused a sensation.[42]

As Gallagher's guitar skills gained recognition, the band began performing at larger venues, including the Arcadia Ballroom, which was run by Peter Prendergast.[43] Prendergast’s brother, Phillip, decided to take on management of the band, securing them support slots for major acts like The Animals.[44] Around this time, Gallagher was also invited by the showband The Victors to play as a session guitarist on their recording 'Call Up the Showbands'.[45]

In June 1965, the band travelled to Spain for a residency at an American Air Force base outside Madrid, in Alcalá de Henares.[37] With Spain under dictatorship at this time, Gallagher was required to cut his hair before entering the country.[46] After their time in Spain, the band recorded their first demo tape, which featured a cover of 'Slow Down' with 'Valley of Tears' as the B-side.[45]

By early summer 1966, The Impact had dissolved.[47] Gallagher, along with bassist Oliver Tobin and drummer Johnny Campbell, formed a trio and started a three-week stint at the Big Apple in Hamburg, Germany.[48][49] They were billed as 'The Fendermen'.[37]

Taste

[edit]1966–1968 Taste Mark 1

[edit]Upon returning to Ireland, Gallagher jammed with local Cork band, The Axills, which featured bassist Eric Kitteringham and drummer Norman Damery, and was offered the position of guitarist.[44] However, having completed a musical apprenticeship in the showbands and influenced by the increasing popularity of beat groups, he decided it was time to form his own band instead and asked Kitteringham and Damery to join him.

Together, they formed The Taste, which was later renamed simply Taste, a blues rock and R&B power trio.[50] The band was formed inside the Long Valley Bar, with the name Taste inspired by a beermat boasting the superior taste of Beamish stout.[42]

Taste began rehearsing on the upper floor of 5 Park View, where the Kitteringham family lived, and made their debut on 10 September 1966 at a school dance held at the Imperial Hotel on Grand Parade in Cork.[25] While Taste performed many covers, they also began developing original material, including an early version of 'Blister on the Moon'.[51]

Looking to expand their reach to Belfast's blues scene, Taste performed at the city's Sammy Houston's Jazz Club on Great Victoria Street in December 1966.[52] Their performance caught the attention of promoter Eddie Kennedy, who offered them a residency at the city's Maritime Hotel and a management deal.[12]

Gallagher persuaded Kitteringham and Damery, who were working as a printer and an insurance broker at the time, to go fully professional, and they agreed. Several months later, Damery's work replacement died in the Aer Lingus 712 flight disaster, leading Damery to tell Gallagher, "Whatever turns out for me professionally now is a bonus. You saved my life".[53]

During their residency at the Maritime Hotel, Taste opened for acts like Cream, Fleetwood Mac and Chris Farlowe & The Thunderbirds, drawing audiences from both Protestant and Catholic communities.[52]

In 1967, the Major-Minor record label, run by Phil Solomon, showed interest in signing Taste and gave them the opportunity to make a demo recording. 'Blister on the Moon' (with B-Side 'Born on the Wrong Side of Time') was subsequently released as a single without Gallagher's consent.[51]

Kennedy's connections with Robert Stigwood, the manager of Cream and the Bee Gees, helped secure gigs for Taste at London's Marquee Club. At their first gig, supporting Robert Hirst and the Big Taste in February 1968, they were billed as 'The Erection' to avoid a name clash.[54] The band’s raw sound made an immediate impression on critics and spectators, leading to a residency offer and a permanent move to London in the summer of 1968.[55]

Polydor began showing interest in signing Taste, but Kennedy claimed the label was unhappy with the current rhythm section.[55] Despite initial resistance from Gallagher, Kitteringham and Damery were replaced by bassist Richard McCracken and drummer John Wilson, both experienced musicians from Belfast who played in the band Cheese, also managed by Kennedy.[50] The change was made amicably, with everyone understanding it was a necessary step for the band's progression.[56]

1968–1970 Taste Mark 2

[edit]

In August 1968, the new line-up of Taste signed with Polydor and relocated to Earl's Court. While living there, Gallagher bought a saxophone and taught himself how to play, practicing in the cupboard of his bedsit to avoid disturbing the other residents.[55]

Three months later, at Eric Clapton's request, Taste supported Cream at their farewell concerts at the Royal Albert Hall. After Cream disbanded, the band's manager Robert Stigwood approached Gallagher with a proposal to join Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker in a new version of the band. Gallagher, however, refused the offer outright.[57]

In early 1969, Taste recorded their eponymous debut album Taste in a single day at De Lane Lea Studios in London. The album was produced by Tony Colton, who had previously produced albums for Yes. Released in April, it included rearranged blues standards like 'Leavin’ Blues', 'Sugar Mama' and 'Catfish', a cover of Hank Snow's 'I'm Movin' On, and Gallagher's own song 'Blister on the Moon', among others. The album was praised by critics for its "raw and honest" sound, selling particularly well in Northern Europe.[25]

In July 1969, Clapton invited Taste to support his new supergroup, Blind Faith, on their US tour. Despite Taste's positive audience reception, the tour was fraught with issues. These included Taste being denied soundcheck time and a proper PA system, playing daytime gigs in large arenas, and tensions with Kennedy over travelling on the musicians' bus and not allowing the band to stay on in the US to play smaller club gigs.[58] During the tour, Gallagher saw Muddy Waters play for the first time at Ungano's in New York.[58]

Once back in London, Polydor requested that Taste begin recording their second album. This time, they were given almost a week to complete the project, which resulted in On the Boards. All ten tracks were composed by Gallagher and showcased his progressive blues style, mixing blues rock with acoustic ballads and experimental jazz-blues fusion. The album was released on January 1970 and reached no. 18 on the UK Albums Chart.[59] Without Gallagher's permission, Polydor issued the opening track 'What's Going On' as a single in Germany, where it became a Top 5 hit.

Throughout 1970, Taste continued to build their reputation as a live band, breaking the Marquee Club's all-time box office record on 21 July, previously held by Jimi Hendrix.[60] John Lennon, who attended one of their performances, told a New Musical Express writer, "I heard Taste for the first time the other day and that bloke is going places".[55]

However, behind the scenes, tensions were escalating due to creative differences and management issues. Gallagher and his brother Dónal were aware that Kennedy was misappropriating funds, but Wilson and McCracken sided with the manager, creating a rift within the group. The situation worsened when Taste's van was broken into the night before the Isle of Wight Festival, and Wilson accused Gallagher of orchestrating the break-in because only his drum pedals were stolen.[25]

Despite these tensions, Taste delivered a strong performance at the Isle of Wight Festival before a crowd of 600,000 people, returning for multiple encores.[55] Their performance was recorded in full by Murray Lerner and later released as the concert film Live at the Isle of Wight (2015).

Gallagher had intended to disband Taste after the Isle of Wight Festival, feeling that the band had "just came to the end of our natural life".[61] However, with Polydor having already scheduled several festival dates and a major European tour, contractual obligations required them to continue. Just three days later, the band performed at the Montreux Jazz Festival, marking the beginning of Gallagher's long relationship with the festival.

Taste's final concert took place at Queen’s University in Belfast on 24 October 1970.[62] Following the breakup, Gallagher would never perform a released Taste song on stage again.[11] McCracken and Wilson would go on to form the rock band Stud.

Despite describing the break-up of Taste as a "traumatic" and "very dreadful time", particularly because "the press all attacked me as if I was some kind of dictator", Gallagher always refused to publicly speak ill of the other band members.[64] He would later reflect on the break-up with regret, describing it as a "communications breakdown" that "shouldn't have been allowed to happen".[41]

Gallagher's brother Dónal, who took on the role of his manager, insisted they bring his previous manager, Eddie Kennedy, to court to recoup royalty payments, but Kennedy capitulated before the case reached trial.[25] He agreed to transfer the Taste royalties, though he claimed to have no money. This meant that Gallagher never received any of the funds generated from Taste's album sales. The episode made Gallagher reluctant to seek out 'big' management deals in future.[65]

Solo career

[edit]1971–1972 Rory Gallagher Band Mark 1

[edit]After the break-up of Taste, Gallagher decided to pursue a solo career and enlisted his brother Dónal as manager. In June 1971, they formed Strange Music to handle the production rights to Gallagher’s songs.[66] Led Zeppelin's manager, Peter Grant was involved in negotiating Gallagher a solo deal with Polydor, which secured him a contract for six albums on more generous terms than previously with Taste.[67]

With a record contract secured with Polydor, Gallagher began assembling a new band. He reached out to Belfast musicians Gerry McAvoy (bass) and Wilgar Campbell (drums), who had previously been part of Deep Joy – a band that had supported Taste in 1970.[68]

Gallagher arranged an audition at Fulham Palace Practising Studios in London and, according to McAvoy, "it gelled from the word go".[69] Gallagher also considered former Jimi Hendrix Experience members Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, before moving forward with McAvoy and Campbell.[51] They made their debut at the Paris Olympia on 30 March 1971.[52] Other performances in 1971 included the Weeley Festival, Reading Festival, and the Crystal Palace Bowl Garden Party, where they performed alongside Elton John, Yes, and Fairport Convention.

Gallagher borrowed money from his mother to make his first solo album Rory Gallagher, which was released in May 1971.[70] The album was recorded at Advision Studios in Fitzrovia, London and self-produced, with sound engineering by Eddy Offord who had previously worked with Gallagher on On the Boards. The album displays Gallagher's folk and jazz influences, with several of its songs carrying a melancholic tone that reflects the emotional impact of the break-up of Taste, such as 'For the Last Time' and 'I Fall Apart'.[71] The album also features keyboard contributions from Vincent Crane, known for his work with Atomic Rooster. Most of the album was recorded without overdubbing: according to Gallagher, it was "the only way to record this sort of music […] just go in and try and get it all first take".[72] The album was reviewed favourably by Melody Maker, which stated: "Gallagher has all the makings to be an absolute monster, and his first album since the break-up of Taste is another pointer in that direction".[73]

Six months later, Gallagher released Deuce, recorded at Tangerine Studios in Dalston, London and again self-produced. Tangerine's staff engineer, Robin Sylvester, described the album as "Rory's 'live self' documented on tape", with all vocals and guitar solos performed live and minimal overdubs.[74] Gallagher told Sounds that he was "happy" with Deuce and felt the mix was "well-balanced", but said that "there's only so much you can get out of a studio".[75] NME saw the album as giving Gallagher’s reputation "a further stride forward" with its "contrastingly different sides of the band's music in rock and roll, blues and a country and western tinged style".[76] Although the album was not a major commercial success at the time of its release, it subsequently gained cult status among fans, with guitarist Johnny Marr calling it "a complete turning point" for him and American comedian Bill Hicks claiming to have worn out several copies.[77]

In December 1971, Gallagher was invited by Muddy Waters to participate in The London Muddy Waters Sessions, playing on three tracks: 'Young Fashion Ways', 'Who's Gonna Be Your Sweet Man When I'm Gone', and 'Key to the Highway'. At the time, Gallagher was on a UK tour and went directly from his concerts to late-night recording sessions.[78] Reflecting later on the experience, he described it as a "special memory", recalling how Waters was "so kind" and had a "spectacular" attitude.[79] The album went on to win a 1972 Grammy Award. Additional tracks from the sessions were released two years later as London Revisited, with Gallagher featuring on three: 'Hard Days', 'I Almost Lost My Mind', and 'Lovin' Man'. During this period, Gallagher also made guest appearances on Mike Vernon’s Bring It Back Home and Chris Barber’s Drat that Fratle Rat!

In 1972, Gallagher was voted "Guitarist of the Year" in a Melody Maker readers' poll.[56] He received an award in the shape of five gold sunbeams, a design later replicated on his headstone at St Oliver's Cemetery in Cork. That year, Gallagher also embarked on his first US solo tour, which included a five-night residency at the Whisky a Go Go in Los Angeles with Little Feat.[52]

According to Gallagher, he "felt very alive at the time in the sense of concerts" and wanted to capture that energy on record, so he decided to record his first live album.[80] The result was Live! in Europe, which was released in May 1972 and featured performances from Luton Technical College, Teatro Lirico in Milan, Space Electronic Club in Florence, and Scala Cinema in Ludwigsburg, Germany. The album entered the top ten of the UK album charts and reached number 101 on the Billboard 200 for 1972.[51] This marked Gallagher's highest-charting album at the time and earnt him his first Gold Disc. Disc and Music Echo described the album as "Rory at his rocking best […] as he holds the stage majestically".[81]

As Gallagher's touring schedule increased, drummer Wilgar Campbell developed a fear of flying. Unable to travel to a concert at the Savoy Theatre in Limerick on 11 May 1972, recorded for Music Makers – RTÉ’s first colour programme – Rod de’Ath of Killing Floor was called in last-minute to replace him.[82] A month later, Campbell again refused to travel for a concert in Lausanne, leading to another replacement by de'Ath. In June 1972, Campbell left the band by mutual consent.

1972–1978 Rory Gallagher Band Mark 2

[edit]Following Campbell’s departure, Rod de'Ath officially took on the role of drummer. Eager to expand the band's sound, Gallagher decided to add a keyboard player and, on De'Ath's recommendation, brought in Lou Martin, who had previously played with him in Killing Floor. The new line-up made their debut on 1 July 1972 in Bellinzona, Switzerland.[52]

In 1973, Gallagher released two studio albums: Blueprint (February) and Tattoo (November), both recorded at Polydor Studios in London, with additional tracks for Blueprint captured at Marquee Studios. Upon release, Blueprint received mixed reviews, with critics acknowledging the potential of Gallagher's new rhythm section but feeling the album reflected a band still in the process of defining their sound. As Melody Maker wrote, "It's not going to change the course of the world, but it'll give you a selection of everything he's so rightly famous for. I'll say it's his most interesting yet".[83] Gallagher himself stated that Blueprint was "more varied and has a very distinct sound", but felt that the "guarded reviews" suggesting he was "on the verge of something new" were "fair".[84][85]

Tattoo, in contrast, was widely praised as representing an expansion of Gallagher's musical palette while retaining his signature sound, enhanced by Martin's keyboard work. According to Guitar Player, "each of the record's nine selections are good, but Rory's guitar licks hold surprises and turn out always to be the high points".[86] Gallagher expressed pride in Tattoo, describing it as "the most vibrant of the albums" with "a mixture of forms".[87] Several tracks, including 'Tattoo'd Lady' and 'A Million Miles Away', went on to become live staples.

In the same year, Gallagher also played on Jerry Lee Lewis's The Session...Recorded in London with Great Artists alongside Albert Lee, Alvin Lee, and Peter Frampton. He contributed to four tracks: 'Music to the Man', 'Jukebox', 'Johnny B. Goode', and 'Whole Lot of Shakin' Goin' On'.

Gallagher and his band regularly performed on TV and radio shows across Europe, including Beat-Club in Bremen, Germany and the BBC's Old Grey Whistle Test.[69] He was one of the most recorded musician of the 1970s by the BBC, appearing on Sounds of the Seventies, Sight and Sound In Concert, and multiple Peel Sessions.[88]

Gallagher toured across North America, Japan, and Europe in 1973, before returning to Ireland for his annual Christmas tour, a tradition he continued throughout the 1970s. The Irish tour coincided with one of the most heightened periods of political unrest in Northern Ireland. Despite the escalating conflict, Gallagher was determined to perform in Belfast – one of the few artists to do so at the time.[89] This approach won him the dedication of thousands of fans and, in the process, he became a role model for other aspiring young Irish musicians.[90][91] This was posthumously recognised with the unveiling of a statue outside the city's Ulster Hall in January 2025.[92]

Gallagher's concerts at Belfast Ulster Hall, Dublin Carlton Cinema, and Cork City Hall were recorded using Ronnie Lane's Mobile Studio and released in July 1974 as the double album Irish Tour ’74. It achieved gold status in the UK and sold over two million copies worldwide.[93] The tour was also captured for a 90-minute music documentary, Irish Tour ’74, directed by Tony Palmer, which was broadcast on the BBC television series Arena. The film premiered in Cork at the Capitol Cinema on 10 June 1974 and was selected as an official entry for the Cork Film Festival.[94]

In January 1975, Gallagher was invited to Rotterdam by Ian Stewart of the Rolling Stones, who were auditioning new guitarists to replace Mick Taylor. He accepted the invitation "just to see what was going on" and jammed with the band for three days.[95] Scheduled to begin a Japanese tour, he left a note with his contact details but did not hear from them again. According to Bill Wyman, Gallagher "played some nice stuff", but Mick Jagger and Keith Richards felt he "wasn't the kind of character that would fit" into the Rolling Stones as he would have to be "subservient to two big egos" and would primarily play solos rather than sing or take a leading role.[96]

In July 1975, Gallagher made his first solo appearance at the Montreux Jazz Festival, where he jammed with Albert King. Although he enjoyed the opportunity to perform with King, Gallagher felt that King was "a little less friendly and a lot more difficult [than Muddy Waters]" and "threw [him] in at the deep end" to stand in for his other guitar player without specifying the running order or keys.[97] The jam session was later released on King’s Live album.

In October 1975, Against the Grain, Gallagher's first album on the Chrysalis label, was released. After considering several offers, he chose Chrysalis because he believed they would provide the "close personal attention" he had previously lacked.[98] The album was recorded at Wessex in Highbury, London and was described by Melody Maker as marking the "beginning of a new era" for Gallagher who had found "a successful recording formula".[99] It featured a cover of Lead Belly's 'Out on the Western Plain' and a reworked version of Bo Carter's 'All Around Man'. At the time, Gallagher described Against the Grain as "the best studio album" to date, as he felt he had finally "made the live thing work" by capturing in the studio what he did on stage.[100]

Calling Card followed one year later, recorded in just four weeks at Musicland Studios in Munich and produced by Deep Purple's Roger Glover. Building on the progression of Against the Grain, the album incorporates elements of blues, rock, funk, jazz, folk, and rockabilly. According to Dónal Gallagher, tensions arose between his brother and Glover because "he couldn't live with somebody else's production" and remixed the album multiple times.[101] Gallagher felt Calling Card had "a good sound" and "good level feeling". [102] Critics praised the album's greater diversity of mood, Gallagher's songwriting, and Glover's ability to "[bring] out a crispness in the band’s playing".[103]

In September 1976, Gallagher undertook a short tour of Poland, invited by the Polish Jazz Society. Despite Poland being under Communist rule at the time, his concerts were officially sanctioned by the Polish government.[11] The concerts attracted many East German fans who risked crossing the border to attend.[104] The event was so significant at the time that it received international press attention.

One month later, Gallagher began his long-standing relationship with the German television concert series Rockpalast, performing both acoustic and electric sets in front of a small audience at Cologne's WDR studios.[52] He returned in July 1977, sharing the bill with Little Feat and the Byrds' Roger McGuinn in what would become the first European-wide broadcast simultaneously on television and radio.[11] Gallagher's performance had an audience of 28 million viewers across Europe.[105] The day before, he had played the Montreux Jazz Festival and travelled directly to Germany for Rockpalast without getting any sleep.[106]

On 26 June 1977, Gallagher headlined the Macroom 'Mountain Dew' Festival, Ireland's first open-air festival, performing before a crowd of 20,000 people.[107] The performance was described by the Irish music magazine Hot Press as "a festival victory, a celebration, two and a half hours of undiluted energy".[108] Hot Press had been launched the month before, with Gallagher appearing on the cover of the inaugural issue. He and his brother Dónal contributed financial support to the magazine's founding.[11]

In October 1977, Irish violinist Joe O'Donnell released the concept album Gaodhal's Vision, with Gallagher contributing guitar to 'Poets and Storytellers' and 'Lament for Coire Sainnte'.

After completing a third tour of Japan in November 1977, Gallagher and his band flew directly to the US to begin working on a new album with producer Elliot Mazer at His Master's Wheels in San Francisco. Gallagher was already acquainted with Mazer, having first met during Taste's 1970 European tour.[109] He also admired Mazer's previous production work on albums such as Neil Young's Harvest, Area Code 615's Trip in the Country, and The Rock by fellow Chrysalis artist Frankie Miller.[110]

According to Gallagher's bassist Gerry McAvoy, the sessions at His Master's Wheels "dragged on for what seemed like an eternity" as Gallagher was dissatisfied with the studio and its equipment.[111] This led to the record's company advance being exceeded, placing a significant financial burden on Gallagher. Tensions within the band were also growing, particularly with drummer Rod De'Ath, who sought more input on the band's direction.[112]

Upon returning home to Cork for Christmas, Gallagher spoke with his brother Dónal and his mother Monica about feeling overwhelmed by the demands of the band and his concerns over the increased costs and financial borrowings associated with the album.[110] However, he returned to San Francisco in the new year, hoping to remix the tracks. After attending the Sex Pistols' final gig on 14 January 1978 at the Winterland Theatre, Gallagher became further convinced that a shift in the band's dynamic and musical direction was necessary.[113]

Ultimately, Gallagher decided to scrap the album on the day it was due to be delivered to Chrysalis. "I didn’t feel convinced when it was finished […] It was something that remixing wouldn't cure. It was a pretty drastic measure, I suppose, but sometimes it's worth it […] It's got to be a record that I can play sometimes myself and enjoy", he explained to Hit Parader.[114] It was after this that Gallagher decided to part ways with Rod de'Ath and Lou Martin, with their final performance taking place at the Hammersmith Odeon on 29 April 1978.[52]

Gallagher later told Good Times that "maybe 80% of the San Francisco album could come out in some form remixed".[115] In 2011, the scrapped album was remixed by Gallager's nephew, Daniel, and released as Notes from San Francisco.

1978–1981 Rory Gallagher Band Mark 3

[edit]After De'Ath and Martin left the band, Gallagher decided to return to a trio format. On the advice of sound engineer, Colin Fairley, he recruited drummer Ted McKenna from the Sensational Alex Harvey Band to join him and bassist Gerry McAvoy.[116] McKenna made his official debut at the Macroom 'Mountain Dew' Festival on 24 June 1978.[52]

Under pressure to deliver a new album to Chrysalis, Gallagher – on the advice of his brother Dónal – chose to record at Dierks Studios in Stommeln, Germany. The studio's residential facilities and home-cooked meals provided a comfortable environment that contrasted with the more impersonal setting of His Master's Wheels in San Francisco.[58]

Produced by Alan O'Duffy, the resulting album, Photo-Finish, was released in October 1978 and featured a rawer rock sound. It included reworked versions of material from the San Francisco sessions, as well as new tracks like 'Shin Kicker' and 'Shadow Play'. The album was reportedly delivered to Chrysalis at "the eleventh hour of the eleventh minute of the eleventh day", a phrase that inspired the album’s title.[58] Gallagher expressed satisfaction with the final result, describing it as "so much more urgent" than the San Francisco version: "this album has a rhythmic fist to it, it kicks. It's funky and it makes its point. It's an independent album".[117] While Way Ahead praised the album’s "crisp and powerful production" and its "furious pace" that "hits you like a ton of bricks", other critics felt the material sounded "overly familiar" and noted the absence of acoustic tracks – a core feature of Gallagher’s earlier albums.[118][119]

Gallagher also took part in various session projects during this time, including Lonnie Donegan's Puttin' on the Style and Mike Batt's Tarot Suite. He collaborated with Frankie Miller to co-write and record the soundtrack for A Sense of Freedom – a Scottish crime film about the Glasgow gangster Jimmy Boyle.

In late 1978, Gallagher was elected Honorary President of the Northern Ireland Guitar Society by its founder, Joseph Cohen.[11] The following year, he was invited to give a guest seminar at the YMCA in Belfast.[120]

In April 1979, Gallagher returned to Dierks Studios to record his eighth studio album Top Priority, produced again by Alan O'Duffy. The album's title referenced Chrysalis's promise that Gallagher would be their "top priority".[58] Released later that year, it marked a continued shift towards a harder rock sound, exemplified by tracks such as 'Bad Penny', 'Follow Me', and 'Philby', the latter inspired by the British double agent Kim Philby. The album received mixed reviews: while Creem praised Gallagher's ability to "push himself" and "still make blues-based material come alive", Melody Maker felt the songs "never really match the magic of the guitar playing".[121][122] According to Dónal Gallagher, the album's harder sound was influenced by record label pressures and the emergence of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, with Gallagher attempting to adapt but remaining somewhat ambivalent.[123] "Well, I just go doing my own thing, whatever it is", Gallagher himself said in 1980, "I think [Top Priority] is modern and valid and moves in its own way".[124]

Throughout 1978 and 1979, Gallagher toured extensively across Europe and the US, becoming one of the first rock artists to perform in Portugal since the Carnation Revolution.[52] It was during this long world tour that he developed a fear of flying after experiencing a bad flight over Norway.[125]

At the 1979 Montreux Jazz Festival, Gallagher was awarded a prize by founder Claude Nobs in recognition of his frequent performances there.[126] The following year, at the Reading Festival, he received an award from Chris Barber for the most headline appearances by any artist at that point, as well as for setting a box office record with over 300,000 tickets sold.[127]

Seeking to capture the band's energy and performance level during the Top Priority world tour, Gallagher released his third live solo album, Stage Struck, in November 1980. The album featured tracks recorded using mobile units at the Agora (Cleveland), Old Waldorf (San Francisco), Stardust Ballroom (Hollywood), Le Chapiteau (Marseille), Halle Rhenus (Strasbourg), and National Stadium (Dublin). Critics praised the album for capturing Gallagher "at his panting best […] with plenty of fortitude and determination".[128]

In February 1981, McKenna played his last concert with Gallagher at the Palais de Sport in Paris.[52] McKenna stated that, although the job was "secure and ongoing", he felt it was time to try something new and explore a different style of music.[129]

1981–1991 Rory Gallagher Band Mark 4

[edit]After auditioning various drummers, Gallagher recruited Brendan O'Neill, a Belfast-born drummer and an old friend of McAvoy's, to join his band. They immediately went into Dierks Studios to record Jinx, which marked a return to Gallagher's blues roots. The album was self-produced and released in May 1982. Although Gallagher felt that Jinx was "me at my most natural" and "returned to the feeling of Tattoo and Against the Grain", it became one of his least commercially successful albums.[130] It struggled due to minimal promotion from Chrysalis, who were undergoing internal restructuring, and was overshadowed by the dominant music trends of the early 1980s.[131] Gallagher later expressed his frustration to Hot Press: "[Jinx] had a lot of plusses that were overlooked at the time. I do take it to heart a wee bit".[132]

In June 1981, Gallagher won the Best Musician category at the Stag/Hot Press Awards.[133]

On 12 September 1981, Gallagher performed at the Nea Filadelfeia Stadium in Athens. Originally expecting 15,000 spectators, the crowd grew to an estimated 40,000, leading to a riot with over 300 people injured and Gallagher temporarily blinded by CS gas.[134] He described the experience as "the most frightening gig I’ve ever done […] I just didn't want to die in a football pitch in Greece, not even knowing what was happening".[135]

On 28 May 1982, Gallagher was presented with a gold statuette for selling out the Glasgow Apollo.[136]

During Gallagher's performance at the Hot Press 5th Birthday Festival at Punchestown Racecourse on 18 July 1982, he was joined on stage by Phil Lynott and Paul Brady – a moment captured on camera by Irish photographer Colm Henry.[137]

Eight years after the Canadian trio Rush had supported Gallagher following the release of their debut album Rush, Gallagher returned the favour by opening for them on the US leg of their Signals tour in late 1982. He later described the experience as "soul-destroying" due to his dislike of performing in large arenas.[138] Keyboardist John Cooke, who joined Gallagher on this tour, would go on to become a regular fixture in the band's live performances moving forward.[131]

In mid-1983, Gallagher began working on a new album to follow up Jinx, with a planned release date in March 1984 under the provisional title Torch. At the time, Gallagher described Torch as "innovative" in terms of sound, with his experimentation in "rhythms and melodies" and heavy use of saxophones intended to "break new ground".[139] However, as time went on, Gallagher became increasingly frustrated with the project and decided to abandon it. He later explained in an interview with Sounds: "One day I just woke up and thought, 'That’s it. It’s over, and that’s the end of that. To hell with it'. And I started laying plans for what became Defender".[140]

Throughout this period, Gallagher remained active in session work, contributing to Gary Brooker's Echoes in the Night and two albums by Box of Frogs (Box of Frogs, Strange Land). He also continued to tour extensively, participating in the Lisdoonvarna Music Festival in Ireland, an Alexis Korner Tribute at the Pistoia Blues Festival in Italy, and an Ethiopia Benefit Concert at Edinburgh’s Usher Hall alongside Charlie Watts, Jack Bruce, and Ian Stewart.[131] He also took part in a series of acoustic concerts, branded as 'Guitarists' Night', with David Lindley, Richard Thompson, and Juan Martín, as well as shows to mark the 25th anniversary of the Marquee Club.[141] It was during the Marquee gigs that Gallagher was first introduced to harmonica player Mark Feltham, who would go on to become a permanent member of the Rory Gallagher Band.[142] Gallagher also toured across Hungary and Yugoslavia, where his concerts were praised by Oslobođenje for making ethnic tensions between the Croats, Slovenes, and Serbs "crumble like a house of cards".[143]

In 1986, Gallagher established his own label, Capo Records, which he said gave him a "fantastic feeling of independence" and "a little identity" for himself.[144] He also signed with the distribution company Demon Records in the UK, praising them for the "artistic trust" they placed in him and understanding his desire to "make some music, record it and put it out" rather than "sell a million records" or participate in "miming sessions for TV".[145]

On 17 May 1986, Gallagher took part in Self Aid – a 14-hour benefit concert to raise money for the unemployment crisis in Ireland. As Gallagher was on a European tour at the time, he flew in directly from France for the event and then travelled straight to Germany for his next show.[146] The concert drew 2.4 million viewers and raised over £500,000.[147]

Gallagher remained musically active throughout the late 1980s, despite a noticeable decline in his health and an increasing reliance on prescription medication.[12]

In July 1987, Gallagher released his highly anticipated tenth studio album Defender, which he viewed as a significant "turning point" in both his career and life.[64] Defender fused Gallagher's passion for the blues with his fascination for hardboiled fiction and film noir, with lyrics delving into themes of law and corruption, such as 'Loanshark Blues', 'Kickback City', and 'Continental Op', a direct homage to the Dashiell Hammett character. Released on Gallagher's own Capo label and distributed by Demon, Defender gained over 60,000 sales, making it one of Demon's all-time Top Ten bestsellers.[131] It also topped the UK Independent Albums Chart and reestablished Gallagher in the public sphere, earning him a spot in Sounds magazine's Reader's Poll of Best Musicians.[131] Gallagher also won Best Album for Defender at the 10th Stag/Hot Press Rock Awards on 1 March 1988.[148] A Hot Press review described Defender as "Gallagher’s most consistent and composed" record with "grittily realistic and not deglamourised versions of the Outlaw Blues myth".[149]

Gallagher also continued to engage in session work, contributing to albums by Irish folk artists The Fureys and Davey Arthur (The Scattering), Davy Spillane (Out of the Air), and Phil Coulter (Words and Music).

On 4 November 1987, Gallagher performed at the Cork Opera House, which was filmed and later broadcast by RTÉ as part of their Christmas concert series.[150] The concert was faithfully recreated by the tribute band Sinnerboy on 29 October 2021.[151]

In February 1988, Gallagher undertook his first Irish tour in four years, which included a four-night run at Dublin's Olympia Theatre. "Gallagher has come back on the scene with the vitality that modern music lacks so much", wrote Paul Russell of the Evening Herald in a review of the concerts.[152] On 17 July 1988, he returned to the Olympia Theatre to participate in the 'Freedom at 70' concert, celebrating the 70th birthday of social rights activist Nelson Mandela.[153]

1989 saw Gallagher headline Irish Rock Week at the Mean Fiddler in London and the Ballyronan Rock Festival in Northern Ireland.[131] He also performed a series of concerts across the UK with jazz musician Chris Barber.[52]

In May 1990, Gallagher released his final studio album Fresh Evidence, which paid tribute to his blues influences while seeking to modernise the genre by "hitting it on the head and coming up with new chord changes and tunes".[154] Recorded with vintage equipment and self-produced, the album took over a year to complete.[131] It featured guest musicians Lou Martin on keyboards, Geraint Watkins on accordion, and brass players John Earle, Ray Beavis, and Dick Hanson. Carol Clerk of Melody Maker noted that Fresh Evidence established Gallagher as "something more than an electric guitar virtuoso" as he "explor[ed] old fields of influence with the authority of someone who has all of the experience to be confident in his craft".[155]

In June 1990, Gallagher was invited to audition for the role of Joey 'The Lips' Fagan in the screen adaptation of the 1987 Roddy Doyle book The Commitments. He ultimately declined the offer, uncomfortable with the script's heavy use of profanity.[156]

After cancelling various shows throughout the summer of 1990 due to ongoing health issues, Gallagher returned to the stage on 17 October 1990 at Rocklife in Cologne.[52] Part of the rebranded Rockpalast series, his performance featured an encore with Jack Bruce. Journalist Chris Welch described the concert as a testament to Gallagher's growth as "a more mature performer".[157]

In late 1990, seeking new challenges and dissatisfied with reduced touring opportunities due to Gallagher's declining health, McAvoy and O'Neill decided to leave Gallagher's band and join the newly reformed Nine Below Zero.[69] They agreed to accompany Gallagher for a final UK tour, followed by a world tour of Japan, Australia, and North America. During Gallagher's concert at the Roxy in Los Angeles, Guns N' Roses' guitarist Slash jammed on stage with him.[158] The tour concluded with a show at New York's Marquee Club on 30 March 1991, which was cut short by the New York Fire and Police Departments due to venue overcrowding.[159]

1991–1992 Interim period

[edit]McAvoy and O’Neill's departure unsettled Gallagher. Tony Palmer, director of the Irish Tour ’74 documentary, observed, "He did his best to keep his feet on the ground, but sometimes it gets to you, and it got to him. I think he felt quite depressed about it".[160] As a result, Gallagher took time to reflect before recruiting new band members, expressing his desire to be "more flexible with the musicians I choose to accompany me" and to "act and to live day to day" without worrying who will be on the next album or the next tour.[161]

By May 1992, Gallagher had not yet assembled a new band, but had a commitment to perform at the Scottish Fleadh in Glasgow. He called upon McAvoy and O'Neill to join him, with violinist Roberto Manes also guesting.[69]

Despite his 14-month hiatus from touring, Gallagher remained involved in music, contributing to the track 'Human Shield' for Stiff Little Fingers' Flags and Emblems album in the summer of 1991. He also participated in an S4C documentary on the history of the Fender Stratocaster.[131] Extended footage later featured in the 2007 documentary Stratmasters.

1992–1995 Rory Gallagher Band Mark 5

[edit]On the recommendation of musician Jim Leverton, Gallagher invited drummer Richard Newman to a rehearsal, who subsequently introduced bassist David Levy. Initially, Gallagher had considered Leverton as bassist, but Leverton ultimately served as a stand-in keyboardist during live performances when John Cooke was unavailable.[131] While the new line-up marked a shift in the band's dynamic, Dónal Gallagher believes his brother was "very happy" with the progression.[162]

The new Rory Gallagher Band made their debut at the Marina Hotel in Rhyl, Wales on 11 August 1992.[52] The following day, Gallagher hosted a masterclass for 50 invited guests at the Guinness Hopstore in Dublin as part of the inaugural Temple Bar Blues Festival.[163] During the masterclass, Ronnie Drew of the Dubliners joined him on stage to perform 'Barley and Grape Rag'. Gallagher was later presented with the Fender/Arbiter Hall of Fame Award, becoming only the second guitarist to receive the honour after James Burton of Elvis Presley's TCB band.[164] On 15 August, Gallagher headlined the Festival, performing a free concert to 20,000 people on the steps of the Bank of Ireland at College Green.[131]

On 30 August 1992, Gallagher headlined the Lark by the Lee in Cork – an annual open-air concert funded by RTÉ 2FM and Cork 89FM Radio.[52] Dave O'Connell of the Evening Examiner described the Lark as "Gallagher’s day", noting "home was the hero and he looked like he was enjoying himself".[165] One day later, Gallagher performed at the city's Everyman Palace Theatre in support of the Irish Red Cross Yugoslav Refugee Appeal.[166]

On 2 September 1992, Gallagher was invited to a civic reception at Cork City Hall, hosted by Lord Mayor Micheál Martin.[167] During the event, he was presented with a special 'Cork Rock Award' Tipperary Crystal in recognition of his musical achievements. In his presentation speech, the Mayor hailed Gallagher as "one of Cork’s greatest sons who has become part of the city’s folklore".[168]

During this period, Gallagher's health continued to deteriorate, which impacted his performance at the Town & Country Club in London on 29 October 1992. The concert ended prematurely after he suffered an adverse reaction to his prescribed medication.[169]

Determined to keep performing, Gallagher pressed on with a European tour, which included a headlining performance at the Bonn Blues Festival on 13 December 1992.[170]

In the same month, Gallagher released the G-Men Bootleg Series Volume 1 through Castle Communications – an attempt to "bootleg the bootleggers" and "set a legal precedent" by reclaiming rights to his own recordings.[171]

When off the road, Gallagher struggled with isolation and restlessness. Seeking to replicate life on the road, Dónal arranged for his brother to move into a suite at the Conrad Hotel in Chelsea Harbour, London, in early 1993.[172] Gallagher was later moved to an apartment block across the street that the hotel serviced due to late-night jam sessions in his room.[131] Although he owned an apartment in Chelsea, Gallagher remained at the Conrad Hotel for the rest of his life, adopting the alias 'Alain Delon', inspired by one of his favourite actors.[173]

On 15 September 1993, Gallagher headlined the 'Curves, Contours and Body Horns' concert at the Manchester Free Trade Hall, celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Fender Stratocaster.[174] The event also featured Frankie Miller, Sherman Robertson, and Sonny Curtis, with proceeds benefitting the charity Relate.

On 18 November 1993, Gallagher performed a special acoustic set in the atrium of Cork Regional Technical College as part of the inaugural Cork Arts Festival.[175] The sold-out concert was a tribute to his late uncle, James (Jimmy) Roche, who was former principal of the College and a significant influence on Gallagher's musical development.[176] This concert would turn out to be Gallagher's final performance in Ireland.[52]

Despite ongoing health challenges, Gallagher performed at festivals across Europe throughout the summer of 1994, including the Pistoia Blues Festival, Montreux Jazz Festival, SDR3 Festival in Stuttgart, and the Festival Interceltique de Lorient.[52] His Lorient show drew a record-breaking crowd at the Kervaric Sports Palace and featured a jam session with Breton musician Dan Ar Braz.[131]

In the final years of his life, Gallagher also continued to engage in session work, including guest appearances on The Dubliners’ 30 Years A-Greying, Energy Orchard’s Remember My Name, Rattlesnake Guitar: The Music of Peter Green, Roberto Manes’ Phoenician Dream, and Samuel Eddy’s Strangers on the Run. He also recorded demos with Bert Jansch and Martin Carthy, released posthumously on the 2003 compilation Wheels Within Wheels.

Gallagher made his final television appearance in the summer of 1994 on Rock ‘n the North, a six-part Ulster Television series exploring Northern Ireland's music history, presented by Terri Hooley.[177]

Gallagher was determined to proceed with his scheduled short tour of the Netherlands in January 1995. However, by the time the tour began on 5 January in Geleen, it was evident that he was "much too sick to give a coherent show".[178] Concerned for his brother's health, Dónal wanted to cancel the remaining concerts, leading to a rare and heated argument between them.[179] Dónal returned to London, but Gallagher remained in the Netherlands, performing in Enschede, Amsterdam, Leeuwarden, and Rotterdam. The Rotterdam show was ultimately cut short due to his failing health, and the remaining dates in Utrecht and Tilburg were cancelled.[131]

Illness and death

[edit]

In the late 1970s, following a turbulent flight over Norway, Gallagher developed a fear of flying, for which he was prescribed medication.[12] This marked the beginning of a gradual decline in health over the final 15 years of his life.[180][181] Despite this, he remained committed to touring and recording, continuing to perform until early 1995 when a final run of concerts in the Netherlands was cut short due to illness.[131]

On returning to London, Gallagher became increasingly reclusive and isolated himself in his Chelsea Harbour apartment.[182] In March, his brother Dónal gained access to the apartment and, concerned about Gallagher's condition, persuaded him to seek treatment at the Cromwell Hospital.[183] There, doctors found that his liver was failing, primarily due to "accidental overdoses of prescription medications over a number of years".[184] They determined that, despite his relatively young age, a liver transplant was the only possible course of action.[185]

Gallagher was transferred to King's College Hospital for the procedure, which was carried out successfully. However, after thirteen weeks in intensive care, while awaiting transfer to a convalescent home, he contracted a staphylococcal (MRSA) infection. He fell into a coma and died on the morning of 14 June 1995, aged 47.[68]

News of Gallagher’s passing came as a shock to many, as his ill health had been kept private.[186] His body was flown back to Cork on 16 June 1995, where it lay at the O'Connor Funeral Home in Temple Hill, allowing family, friends, and fans to pay their respects.

On the morning of 19 June 1995, Gallagher's funeral cortege was driven through the streets of Cork City, passing MacCurtain Street, where he grew up.[187] The funeral took place at the Church of the Descent of the Holy Spirit in Dennehys Cross. Several musicians were present, including The Edge and Adam Clayton of U2, Martin Carthy, members of The Dubliners, Clannad, and Gary Moore.[56] Former band members also participated in the ceremony, with Mark Feltham performing 'Amazing Grace' on the harmonica and Lou Martin playing a piano rendition of Gallagher's song 'A Million Miles Away'.[56]

Gallagher was buried in St Oliver's Cemetery, Ballincollig, just outside Cork City. His grave's headstone is designed to resemble the Melody Maker "Guitarist of the Year" award he received in 1972.[188]

On 8 November 1995, a memorial service was held at Brompton Oratory in London. The service ended with a tribute from Hot Press editor Niall Stokes who described Gallagher as a "pioneer" who blazed a trail through the "musical darkness" in 1970s Ireland, "illuminating the magical electrifying possibilities that rock ‘n’ roll could offer, for thousands upon thousands of young Irish fans".[189]

Personal life

[edit]Gallagher was committed to his craft and treated music "like a vocation in the priesthood".[190] He never married, had no long-term relationships, and had no children.[48] Often described as shy and introverted, he led "a solitary unindulgent life away from stage", avoiding the excesses commonly associated with the rockstar lifestyle.[48]

Outside of music, Gallagher was an avid reader, particularly of hardboiled fiction. His favourite authors included Patricia Highsmith, Dashiell Hammett, and Raymond Chandler.[191] He also enjoyed film noir and cited Purple Noon, an adaptation of Highsmith’s novel The Very Talented Mr Ripley, as one of his favourite films.[192] These influences frequently appeared in his songwriting, as reflected in songs like 'Continental Op', 'In Your Town', and 'Big Guns'.

Gallagher also had an interest in visual arts and enjoyed painting and drawing. During his early showband years, he attended evening classes at Crawford School of Art in Cork.[193]

Band line-up

[edit]In addition to Gallagher himself (on guitar and vocals), over the years Gallagher's band included:

- 1971–1972: Gerry McAvoy (bass) and Wilgar Campbell (drums)[194]

- 1972–1978: Gerry McAvoy (bass), Rod de'Ath (drums), and Lou Martin (keyboards)[194][25][195]

- 1978–1981: Gerry McAvoy (bass) and Ted McKenna (drums)[56]

- 1981–1991: Gerry McAvoy (bass), Brendan O'Neill (drums), and frequent guest Mark Feltham (harmonica)[56]

- 1992–1994: David Levy (bass), Richard Newman (drums), John Cooke (keyboards) and frequent guest Mark Feltham (harmonica).[131]

A number of guest musicians also recorded and played with Gallagher and his band, including:[131]

- 1981, 1986–1987: Bob Andrews, keyboards (Jinx, Defender)

- 1981–1982: Dick Parry, tenor saxophone (live performances, Jinx)

- 1981–1982, 1989–1990: Ray Beavis, tenor saxophone (live performances, Jinx, Fresh Evidence)

- 1982: Howie Casey, tenor saxophone (live performances)

- 1989–1990: Geraint Watkins, piano and accordion (Fresh Evidence, live performances)

- 1990: John 'Irish' Earle, tenor saxophone and baritone saxophone (Fresh Evidence)

- 1990: Dick Hanson, trumpet (Fresh Evidence)

- 1992–1994: Jim Leverton, keyboards and bass (live performances)

- 1994: Frank Mead, harmonica and saxophone (live performances)

Guitars and equipment

[edit]1961 Fender Stratocaster

[edit]

The main instrument that Gallagher played throughout his career was a sunburst 1961 Fender Stratocaster (Serial Number 64351).[25] It was reputedly the first in Ireland,[196] and originally owned by Jim Conlon, lead guitarist in the Irish band Royal Showband.[197][198] Gallagher bought it second-hand from Crowley's Music Shop of Cork's MacCurtain Street in August 1963 for £100.[199][200] Speaking about Gallagher's purchase, his brother Dónal recalled: "His dream ambition was to have a guitar like Buddy Holly. This Stratocaster was in the store as a used instrument, it was 100 pounds. In today's money you couldn't even compare; you might as well say it was a million pounds. My mother was saying we'll be in debt for the rest of our lives and Rory said, 'Well, actually with a guitar like this I can play both parts, rhythm and lead, we won't need a rhythm player so I can earn more money and pay it off.' So the Stratocaster became his partner for life if you like".[201]

In 1967, while in Dublin to visit Pat Egan at the Five Club, Gallagher's Stratocaster was stolen, along with a Telecaster he had borrowed from a friend. Gallagher contacted the producers of a television programme called Garda Patrol, who featured the stolen guitars in one of their segments. A few days later, the Stratocaster was discovered abandoned in a ditch behind a garden wall on the South Circular Road and was returned to him.[39]

Virtually all of the finish on Gallagher's Stratocaster was stripped away over time, and, while he took care to keep the guitar in playable condition, Gallagher never had it restored, stating "the less paint or varnish on a guitar, acoustic or electric, the better. The wood breathes more. But it’s all psychological. I just like the sound of it".[202] Gallagher's brother Dónal has also stated that, owing to his rare blood type,[203] Gallagher's sweat was unusually acidic, acting to prematurely age the instrument's paintwork.[202]

The guitar was extensively modified by Gallagher. The tuning pegs and the nut were replaced,[204] the latter changed a number of times. The pickguard was also changed during Gallagher's time with Taste. Only the middle pick-up is original. The final modification was the wiring – Gallagher disconnected the bottom tone pot and rewired it so he had just a master tone control along with the master volume control. He installed a five-way selector switch in place of the vintage three-way type.[204]

Speaking of the Stratocaster in a 1993 interview, Gallagher said, "This is the best, it's my life, this is my best friend. It's almost like knowing its weak spots are strong spots. I don't like to get sentimental about these things, but when you spend 30 years of your life with the same instrument, it's like a walking memory bank of your life there in your arms".[205]

In late October 2011, Dónal Gallagher brought the guitar out of retirement to allow Joe Bonamassa to perform with it on his two nights at the Hammersmith Apollo in London. Bonamassa used it to open both nights' performances with his rendition of 'Cradle Rock'.[206]

In July 2024, Dónal Gallagher announced that he would be auctioning the Stratocaster through Bonhams.[207][208] The guitar was sold later in 2024 for £700,000. The buyer, the concert promoter Denis Desmond, made the purchase following discussions with the Irish Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, with the intention of donating the guitar to the National Museum of Ireland (NMI).[209] On 5 February 2025, it was announced that the Stratocaster would be put on display by the NMI from September 2025.[210]

Other instruments

[edit]Although most widely associated with his 1961 Fender Stratocaster, Gallagher also used a number of other guitars throughout his career.[211] In his early years, he favoured a 1966 Fender Telecaster or 1959 Fender Esquire for electric slide work, and a 1968 Martin D35 or 1932 National Triolian Resonator for acoustic.[212] Later, he tended to use a 1963 Gretsch Corvette for electric slide guitar and replaced his Martin with a 1980 Takamine Dreadnought Style Acoustic.[131] His 1942 Martin mandolin was used most famously on 'Going to My Hometown', while his 1968 Coral 3S19 electric sitar was used for live renditions of 'Philby'. His 1968 Selmer alto saxophone is most associated with Taste’s On the Boards (1970) album.

Other equipment

[edit]While Gallagher's sound is frequently attributed to his use of a Vox AC30 amp and Dallas Rangemaster Treble Booster, his rigs evolved throughout his career. He typically preferred smaller 'combo' amplifiers to more powerful Marshall stacks popular with rock and hard rock guitarists.[213] To make up for the relative lack of power on stage, he would link several different combo amps together.[214]

- 1963–1973: Vox AC30 with Dallas Rangemaster Treble Booster

- 1973–1977: 1956 Fender Twin/1954 Fender Bassman

- 1977–1978: Fender Bassman linked with 1960 Fender Concert, sometimes with Hawk II Expander/Booster

- 1978–1979: Ampeg VT-40 linked with Ampeg VT-22, sometimes with Hawk II Expander/Booster, but later replaced with a Furman PQ-3 Parametric EQ. Sometimes two Marshall 50-watt JMP combos, hooked with Boss DB-5 pedal

- 1979–1981: Ampeg VT-20 combined with 50-watt Marshall

- 1981–1985: Vox AC30 with Marshall 50-watt combo

- 1985–1992: Vox AC30 with two Marshall heads and speaker cabinets

- 1992–1995: Vox AC30/Marshall 50-watt combo with Marshall 100-watt Super Bass amp, atop a 4X12 cabinet, along with Boss DB-5 pedal and DOD 680 delay[215][216][131]

Although Gallagher remained "very wary" of guitar effects and pedals, preferring to extract as much as possible from the guitar and amp themselves, he began to experiment with effects more gradually throughout the 1980s, including:[217]

- Ibanez TS808 Tube Screamer

- Script-logo MXR Dyna Comp

- Boss BF-2 flanger

- OC-2 Octaver

- Boss OD-1

- Boss ROD-20

- Boss ME-5[218][219][131]

Throughout his career, Gallagher preferred Fender Rock 'n' Roll 150 strings for his electric guitars and Martin medium gauge strings for his acoustics. For electric guitar, he typically used Herco Flex 75 picks, while for acoustic, he preferred Fender tortoiseshell picks.[220]

Early on, Gallagher used a brass slide for slide guitar, but later switched to a glass Coricidin medicine bottle for a softer tone. He continued using brass slides for acoustic work, particularly on his National.[221] By the early 1980s, Gallagher returned to a brass slide for electric guitar, but also experimented with steel socket wrenches, which he described as "fantastic" despite their tendency to fatigue his hand. [222] When using a capo, he preferred the Bill Russel model.

Legacy

[edit]Influence on musicians

[edit]Brian May, lead guitarist of Queen, has credited Gallagher with helping him discover his sound. May often attended Taste's performances at the Marquee Club in London. One evening, May stayed behind and asked, "How do you get your sound, Mr Gallagher?" [18] The sound to which May refers consists of a Dallas Rangemaster Treble Booster in combination with a Vox AC30 amplifier. The next day, May went out and a purchased the same equipment. "He’s in my life always", May reflected in a 2021 interview with Far Out.[223]

Slash, lead guitarist with Guns N’ Roses, has referred to Gallagher as "a really big influence on me" and "one of the all-time great guitar players".[224] He still considers their jam together at the Roxy in 1991 as "one of the biggest thrills" of his life.[225]

For The Edge of U2, Gallagher was an inspiration on multiple levels, not only for being Irish and achieving success but also for his stage presence, which he describes as "an absolute eye-opener, a mind-blower".[226] According to The Edge, Gallagher’s performances gave "a boost to [his] morale" and "a new lease of determination and energy" when he started out as a musician.[227]

Johnny Marr, known for his work with The Smiths, describes Gallagher as "a beacon".[228] Purchasing Deuce when he was 14 years old and seeing Gallagher perform in Manchester left a "massive impression" on him.[229] In the Ghost Blues documentary, Marr told the story of how he used a blowtorch in woodshop class to replicate the worn look of Gallagher's battered Stratocaster.[230]

Jake Burns, the frontman of Stiff Little Fingers, became a Gallagher fan after watching Taste's farewell concert on the BBC in 1970. He recalls being "frozen in [his] tracks" by Gallagher's sound and credits him as "the main reason" he picked up a guitar.[231]

Glenn Tipton of Judas Priest considers Gallagher his "main inspiration": "I saw him play in Taste many times, and he really inspired me—not just musically but also through the energy and feeling he projected".[232]

Alex Lifeson of Rush has expressed how "really impressed" he was with Gallagher's guitar playing, noting his energetic performances and unique blues style, which he felt was "a reflection of his soul".[233] Lifeson recalls Gallagher's approachability when Rush opened for him on his 1974 North American tour, as well as the time Gallagher opened for them in 1982: "It wasn't just about the music; it was his personality and his soul. He was so thoughtful and considerate to others, so polite. Honestly, he was such a wonderful person, beyond his incredible talents and skills".[234]

Guitarist Ritchie Blackmore has described Gallagher as "probably the most natural player I’ve ever seen", noting that "in all the gigs we did together I don’t think I ever heard him play the same thing twice... He was the ultimate performer".[235]

In the Hot Press Rory Gallagher 25th anniversary tribute, Mick Fleetwood reflected: "From the first note I heard him play, we in Fleetwood Mac knew he had the magic! Rory was committed to every note he played! No surprise because he loved his life as a messenger bringing his music to us all. What shone then still shines now!"[236]

Robert Smith of The Cure told Far Out that his very first concert was Rory Gallagher: "He was a genius […] I came away from that gig thinking it was so fucking excellent that I went on a series of Brighton jaunts for the next few years to see whoever was playing".

Other musicians to cite Gallagher as an influence include The Edge from U2, Janick Gers of Iron Maiden,[237] James Dean Bradfield of Manic Street Preachers,[238] Vivian Campbell of Def Leppard,[239] Gary Moore,[240] Joe Bonamassa,[40][241] and Davy Knowles.[242]

Several artists have written tribute songs in honour of Gallagher, including Christy Moore, Dan Ar Braz, John Spillane, Larry Miller, and Eamonn McCormack.

Festivals

[edit]Since 2002, the Rory Gallagher International Tribute Festival has been held annually in Ballyshannon, attracting approximately 8,000 spectators.[243] Smaller-scale tribute events are also held annually in Nantwich, Wijk aan Zee, Bergamo, and Tokyo.

In May 2025, Cork City Council, in collaboration with the Rory Gallagher estate, announced 'Cork Rocks for Rory'. Running 14 June to 4 July 2025, it aims to celebrate Gallagher's musical legacy in his hometown of Cork. The programme includes the launch of a permanent walking trail, a series of exhibitions, and three 'Live at the Marquee' concerts by American blues guitarist Joe Bonamassa celebrating Gallagher's music.[244]

Posthumous releases

[edit]Since Gallagher's passing, his estate, managed by his brother Dónal and nephews Daniel and Eoin, have overseen the release of posthumous material, including previously unheard recordings and live performances.

Wheels Within Wheels (2003) sought to fulfil Gallagher's lifelong ambition to release an acoustic album. The album featured collaborations with Bert Jansch, Martin Carthy, The Dubliners, Juan Martín, and Lonnie Donegan.

Notes from San Francisco (2011), based on the previously unreleased album that Gallagher abandoned prior to the release of Photo-Finish, offers insight into the potential direction his collaboration with producer Elliot Mazer might have taken.

Kickback City (2013) combined Gallagher's music with his passion for hardboiled fiction, complemented by an accompanying novella produced by Ian Rankin.

The BBC Sessions (1999), Beat Club Sessions (2010), and Taste - Live at the Isle of Wight (2015) each showcase Gallagher’s live performance abilities.

The three-disc album Blues (2019) debuted at number four on the Top 50 Official Irish Albums Chart, while the live album Check Shirt Wizard – Live in ‘77 (2020) topped the Billboard Blues Album Chart.[245][246]

Other releases include 50th anniversary editions of Rory Gallagher (2021) and Deuce (2022), All Around Man – Live in London (2023) featuring highlights from Gallagher’s two concerts at the Town & Country Club in December 1990, and Record Store Day LPs such as Cleveland Calling Parts 1 and 2 and Live in San Diego ‘74.

2024 saw the release of a new documentary, Rory Gallagher: Calling Card and the boxset Rory Gallagher: The BBC Collection.

Tributes

[edit]| November 1995 | Rue Rory Gallagher unveiled in Ris-Orangis, a commune in the southern suburbs of Paris[247] |

| November 1995 | Inaugural Rory Gallagher Memorial Lecture at Cork Regional Technical College[248] |

| June 1996 | Hot Press Rory Gallagher Rock Musician Award established[249] |

| 1997 | Fender production of Custom Shop Rory Gallagher Stratocaster[250] |

| 25 October 1997 | Tribute sculpture unveiled in newly renamed Rory Gallagher Place (formerly St Paul's St. Square) in Cork[251] |

| February 1999 | Induction into the Blues Hall of Fame in Memphis, Tennessee[252] |

| 1999 | Plaque unveiled outside former site of Star Club in Hamburg[253] |

| 2000 | Plaque unveiled on the Rock Hospital in Ballyshannon where Gallagher was born[254] |

| 2002 | Set of Rory Gallagher stamps produced by Irish postal service An Post[255] |

| 2004 | Rory Gallagher Music Library opens in Cork[256] |

| June 2006 | Unveiling of Rory Gallagher Corner at Meeting House Square in Dublin's Temple Bar, with a full-size bronze representation of his Stratocaster[257] |

| 2006 | Plaque unveiled at Ulster Hall in Belfast[258] |

| 2010 | Flynn Amps begin manufacturing a Rory Gallagher signature Hawk pedal, cloned from Gallagher's 1970s pedal[259] |

| 2 June 2010 | Life-sized bronze statue of Gallagher, made by Scottish sculptor David Annard, unveiled in town centre of Ballyshannon[260] |

| 2013 | Winner of Tommy Vance Inspiration Awards by Classic Rock magazine[261] |

| 14 June 2015 | Shandon Bells in Cork ring out 'Tattoo'd Lady' to mark the 20th anniversary of Gallagher's passing.[262]

Camden Palace Hotel Community Arts Centre on Camden Quay renames music studio in Gallagher’s honour. |

| March 2018 | Rory Gallagher Boardroom unveiled at Fender HQ in Ireland[263] |

| March 2018 | Central Bank of Ireland releases a Rory Gallagher commemorative coin[264] |

| 2020 | Gallagher inducted into the Vintage Guitar Hall of Fame[265] |

| June 2020 | Hot Press release a commemorative edition to mark the 25th anniversary of Gallagher's passing[266] |

| 2021 | Gallagher's Telecaster is displayed at the 1971 Reading Festival exhibition in Reading, UK[267] |

| June 2021 | Cork poet laureate William Wall writes the poem 'Hometown Blues' about Gallagher[268] |

| August 2021 | Gallagher voted winner of Ireland's Greatest Music Artist by Newstalk Radio[269] |

| March 2022 | Hot Press launches a Rory Gallagher performance series[270] |

| April 2023 | Cobh International Readers and Writers Festival dedicated to Gallagher. Plaque unveiled on 19 West Beach where Gallagher and his brother Dónal spent time as children[271] |

| May 2024 | Anselm McDonnell's composition 'Gallagher' wins the Seán Ó Riada composition competition and is premiered at the Cork International Choral Festival[272] |

| October 2024 | Auction of the Rory Gallagher Collection at Bonhams, including Gallagher’s 1961 Fender Stratocaster[273] |

| 4 January 2025 | Statue of Gallagher unveiled outside Ulster Hall in Belfast. Inspired by a January 1972 Melody Maker magazine cover shot of Gallagher and sculpted by Anto Brennan and Bronze Art Ireland’s Jessica Checkley and David O’Brien.[274] |

| 16 June 2025 | Renaming of main entrance road to Cork Airport as Rory Gallagher Avenue. Unveiled by An Taoiseach Micheál Martin[275] |

Selected discography

[edit]Gallagher released 14 albums during his lifetime as a solo act, which included three live albums:

- Rory Gallagher (1971)

- Deuce (1971)

- Live in Europe (1972)

- Blueprint (1973)

- Tattoo (1973)

- Irish Tour '74 (1974)

- Against the Grain (1975)

- Calling Card (1976)

- Photo-Finish (1978)

- Top Priority (1979)

- Stage Struck (1980)

- Jinx (1982)

- Defender (1987)

- Fresh Evidence (1990)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Rory Gallagher's birth certificate". Flickr. 9 December 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ O'Hagan, Lauren Alex (28 June 2021). "'Rory played the greens, not the blues': expressions of Irishness on the Rory Gallagher YouTube channel". Irish Studies Review. 29 (3): 348–369. doi:10.1080/09670882.2021.1946919. S2CID 236144825.

Irish fans often mock non-Irish fans for pronouncing [Gallagher's name] with a hard 'g' (/ˈgæləɡə/) instead of a soft 'g' (/ˈgæləhə/): 'it's Gall-a-HER, not Gall-AGG-er'; 'Galla-her: the second g is silent.'

- ^ "Rory Gallagher". AllMusic. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ "Paying tribute to Rory Gallagher Ireland's first rock star". RTÉ Archives. RTÉ.

- ^ Wardle, Drew (2 March 2021). "Rory Gallagher the greatest guitarist you've never heard of". faroutmagazine.co.uk. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Peacock, Tim (2 March 2022). "Why Guitar God Rory Gallagher Was Ireland's Hendrix And Clapton Rolled into One". uDiscover Music. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ "Ballad of a Thin Man". Mojo. October 1998 – via roryon.com.

- ^ a b "Archives - Rory's Story". RoryGallagher.com.

- ^ "Extract from Riding Shotgun biography – Prologue: Can't Believe It's True". Ridingshotgun.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 January 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ "The A-Z of Irish Music: G — Rory Gallagher Biography". Irish Connections. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f O'Hagan, Lauren Alex; Morales, Rayne (2024). Rory Gallagher: The Later Years. WP Wymer.

- ^ a b c d e O'Hagan, Lauren Alex (10 March 2022). "Fashioning the "People's Guitarist" The Mythologization of Rory Gallagher in the International Music Press". Rock Music Studies. 9 (2): 174–198. doi:10.1080/19401159.2022.2048988. S2CID 247393495.

- ^ Stanton, Scott. (2003). The Tombstone Tourist: Musicians. Simon & Schuster. p. 319. ISBN 0-7434-6330-7.

- ^ "Rory Gallagher: Tributes to an Irish rock legend". BBC News.

- ^ "An Post: Celebrating Irish musical icons through the years". Hot Press.

- ^ "Rory Gallagher coin issued to mark 70th birthday". BBC News.

- ^ "Rory's Rock 'n Stroll". Rory Gallagher Festival.

- ^ a b "Dvdverdict.com". 15 April 2009. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ Carty, Pat (10 July 2020). "Johnny Marr on Rory Gallagher - The Full Hot Press Interview". Hot Press.

- ^ "Joan Armatrading reflects on Rory Gallagher's remarkable legacy". Hot Press.

- ^ Ling, Dave (20 December 2024). ""I'm not Rory; I don't want to be a tribute act": Joe Bonamassa on paying homage to Rory Gallagher in Ireland". Classic Rock.

- ^ Grossman, Stefan (March 1978). "Rory Gallagher: Irish Guitar Star With Roots in American Blues and Rock". Magazine. Guitar Player magazine. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ a b "RTÉ Archives – Profile – Rory Gallagher". rte.ie. RTÉ. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Interview with Donal Gallagher". Donegal Democrat. June 2000 – via RoryOn.com.