Pervez Musharraf

Pervez Musharraf | |

|---|---|

پرویز مشرف | |

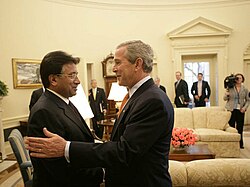

Musharraf in 2008 | |

| 10th President of Pakistan | |

| In office 20 June 2001 – 18 August 2008 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Muhammad Rafiq Tarar |

| Succeeded by | Muhammad Mian Soomro (acting) |

| Chief Executive of Pakistan | |

| In office 12 October 1999 – 21 November 2002 | |

| President | Muhammad Rafiq Tarar |

| Preceded by | Nawaz Sharif (Prime Minister) |

| Succeeded by | Zafarullah Khan Jamali (Prime Minister) |

| Minister of Defence | |

| In office 12 October 1999 – 23 October 2002 | |

| Preceded by | Nawaz Sharif |

| Succeeded by | Rao Sikandar Iqbal |

| 10th Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee | |

| In office 8 October 1998 – 7 October 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Jehangir Karamat |

| Succeeded by | Aziz Khan |

| 7th Chief of Army Staff | |

| In office 6 October 1998 – 29 November 2007 | |

| President |

|

| Prime Minister | See list

|

| Preceded by | Jehangir Karamat |

| Succeeded by | Ashfaq Parvez Kayani |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Syed Pervez Musharraf 11 August 1943 Delhi, British India |

| Died | 5 February 2023 (aged 79) Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Resting place | Army Graveyard, Karachi |

| Citizenship |

|

| Political party | All Pakistan Muslim League |

| Other political affiliations | Pakistan Muslim League (Q) |

| Spouse |

Sehba (m. 1968) |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | |

| Awards | Full list |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1964–2007 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | Regiment of Artillery |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Political views

Elections

Parties

President of Pakistan

Bibliography

|

||

Pervez Musharraf[a] (11 August 1943 – 5 February 2023) was a Pakistani military officer and politician who served as the tenth president of Pakistan from 2001 to 2008.

Prior to his career in politics, he was a four-star general and appointed as the chief of Army Staff and, later, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff by prime minister Nawaz Sharif in 1998. He was the leading war strategist in the Kargil infiltration that brought India and Pakistan to a brink of war in 1999. When prime minister Sharif unsuccessfully attempted to dismiss general Musharraf from his command assignments, the Army GHQ took over the control of the civilian government, which allowed him to control the military and the civilian government.

In 2001, Musharaff seized the presidency through a legality and a referendum but was constitutionally confirmed in this capacity in 2004. With a new amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan, his presidency sponsored the premierships of Zafarullah Jamali and later Shaukat Aziz and played a sustaining and pivotal role in American-led War on terror in Afghanistan.

On social issues, his presidency promoted the social liberalism under his enlightened moderation program; and on economic front, the privatization and economic liberalization was aggressively pursued though the Aziz's premiership that sharply rose the overall gross domestic product (GDP). Without the meaningful reforms and the continued banned on the trade unions, the decline of social security, and the economic inequality rose at a rapid rate. The Musharraf presidency also suffered with containing the religiously-motivated terrorism, violence, tribal nationalism, and the fundamentalism. His presidency was also accused of violating the basic rights granted in the constitution. In 2007, he attempted to seized the control of the Supreme Court by approving the relieve of the Chief Justice of Pakistan, and later suspended the writ of the constitution, which led to fall of his presidency dramatically when he resigned to avoid impeachment in 2008.

In 2013, Musharraf returned to Pakistan to participate in the general election but was later disqualified from participating when lawsuits were filed against him in the country's high courts alleging involvement in the assassinations of nationalists Akbar Bugti and Benazir Bhutto. Furthermore, Prime Minister Sharif instructed his administration to open an inquiry and filed a proceeding in Supreme Court regarding the suspension of the writ of the constitution in 2007.

In 2014, Musharraf was declared an "absconder" in the Bugti and Bhutto assassination cases by virtue of moving to Dubai due to failing health.[1] Finally in 2019, the Special Court found Musharraf of guilty of violating the constitution in 2007, and upheld a verdict that sentenced him to death in absentia.[2][3] Musharraf died at age 79 in Dubai in 2023 after a prolonged case of amyloidosis. His legacy is seen as mixed; his time in power saw the emergence of a more assertive middle class, but his open disregard for civilian institutions greatly weakened democracy and the state of Pakistan.[4][5]

Early life

British India

Musharraf was born on 11 August 1943 to an Urdu-speaking family in Delhi, British India,[6][7][8] the son of Syed Musharrafuddin[9] and his wife Begum Zarin Musharraf (c. 1920–2021).[10][11][12][13][14] His family were Muslims who were also Sayyids, claiming descent from the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[15] Syed Musharraf graduated from Aligarh Muslim University and entered the civil service, which was an extremely prestigious career under British rule.[16] He came from a long line of government officials as his great-grandfather was a tax collector while his maternal grandfather was a qazi (judge).[9] Musharraf's mother Zarin, born in the early 1920s, grew up in Lucknow and received her schooling there, after which she graduated from Indraprastha College at Delhi University, taking a bachelor's degree in English literature. She then married and devoted herself to raising a family.[7][15] His father, Syed, was an accountant who worked at the foreign office in the British Indian government and eventually became an accounting director.[9]

Musharraf was the second of three children, all boys. His elder brother, Javed Musharraf, based in Rome, is an economist and one of the directors of the International Fund for Agricultural Development.[17] His younger brother, Naved Musharraf, is an anaesthesiologist based in the state of Illinois, in the United States.[17]

At the time of his birth, Musharraf's family lived in a large home that belonged to his father's family for many years called Nehar Wali Haveli, which means "House Next to the Canal".[9] Sir Syed Ahmed Khan's family lived next door. It is indicative of "the family's western education and social prominence" that the house's title deeds, although written entirely in Urdu, were signed by Musharraf's father in English.[18]

Pakistan and Turkey

Musharraf was four years old when India achieved independence and Pakistan was created as the homeland for India's Muslims. His family left for Pakistan in August 1947, a few days before independence.[11][18][19] His father joined the Pakistan Civil Services and began to work for the Pakistani government; later, his father joined the Foreign Ministry, taking up an assignment in Turkey.[11] In his autobiography In the Line of Fire: A Memoir, Musharraf elaborates on his first experience with death, after falling off a mango tree.[20]

Musharraf's family moved to Ankara in 1949, when his father became part of a diplomatic deputation from Pakistan to Turkey.[16][21] He learned to speak Turkish.[22][23] He had a dog named Whiskey that gave him a "lifelong love for dogs".[16] He played sports in his youth.[11][24] In 1956, he left Turkey[16][21] and returned to Pakistan in 1957[22] where he attended Saint Patrick's School in Karachi and was accepted at the Forman Christian College University in Lahore.[16][25][26] At Forman, Musharraf chose mathematics as a major in which he excelled academically, but later developed an interest in economics.[27]

Military career

In 1961, at the age of 18,[15] Musharraf entered the Pakistan Military Academy at Kakul.[24][28] At the Academy, General Musharraf formed a deep friendship with General Srilal Weerasooriya, who went on to become the 15th Commander of the Sri Lankan Army. This enduring camaraderie between the two officers played a pivotal role in cultivating robust diplomatic and military ties between Pakistan and Sri Lanka in the years that followed.[29][30][31][32][33][34]

Also during his college years at PMA and initial joint military testings, Musharraf shared a room with PQ Mehdi of the Pakistan Air Force and Abdul Aziz Mirza of the Navy (both reached four-star assignments and served with Musharraf later on) and after giving the exams and entrance interviews, all three cadets went to watch a world-acclaimed Urdu film, Savera (lit. Dawn), with his inter-services and college friends, Musharraf recalls, In the Line of Fire, published in 2006.[15]

With his friends, Musharraf passed the standardised, physical, psychological, and officer-training exams, he also took discussions involving socioeconomics issues; all three were interviewed by joint military officers who were designated as Commandants.[15] The next day, Musharraf along with PQ Mehdi and Mirza, reported to PMA and they were selected for their respective training in their arms of commission.[15]

Finally, in 1964, Musharraf graduated with a Bachelor's degree in his class of 29th PMA Long Course together with Ali Kuli Khan and his lifelong friend Abdul Aziz Mirza.[35] He was commissioned in the artillery regiment as second lieutenant and posted near the Indo-Pakistan border.[35][36] During this time in the artillery regiment, Musharraf maintained his close friendship and contact with Mirza through letters and telephones even in difficult times when Mirza, after joining the Navy Special Service Group, was stationed in East-Pakistan.[15]

Indo-Pakistani conflicts (1965–1971)

His first battlefield experience was with an artillery regiment during the intense fighting for the Khemkaran sector in the Second Kashmir War.[37] He also participated in the Lahore and Sialkot war zones during the conflict.[23] During the war, Musharraf developed a reputation for sticking to his post under shellfire.[19] He received the Imtiazi Sanad medal for gallantry.[21][24]

Shortly after the end of the War of 1965, he joined the elite Special Service Group (SSG).[22][35] He served in the SSG from 1966 to 1972.[22][38] He was promoted to captain and to major during this period.[22] During the 1971 war with India, he was a company commander of an SSG commando battalion.[23] During the 1971 war he was scheduled to depart to East Pakistan to join the army-navy joint military operations, but the deployment was cancelled after Indian Army advances towards Southern Pakistan.[15]

Staff appointment, student officer, professorship and brigade commander (1972–1990)

Musharraf was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1974;[22] and to colonel in 1978.[39] As staff officer in the 1980s, he studied political science at the National Defence University (NDU), and then briefly tenured as assistant professor of war studies at the Command and Staff College and then assistant professor of political science also at NDU.[35][36][38] One of his professors at NDU was general Jehangir Karamat who served as Musharraf's guidance counsellor and instructor who had significant influence on Musharraf's philosophy and critical thinking.[40] He did not play any significant role in Pakistan's proxy war in the 1979–1989 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.[38] In 1987, he became a brigade commander of a new brigade of the SSG near Siachen Glacier.[8] He was personally chosen by then-President and Chief of Army Staff general Zia-ul-Haq for this assignment due to Musharraf's wide experience in mountain and arctic warfare.[41] In September 1987, Musharraf commanded an assault at Bilafond La before being pushed back.[8]

He studied at the Royal College of Defence Studies (RCDS) in Britain during 1990–91.[23] His course-mates included Major-generals B. S. Malik and Ashok Mehta[41] of the Indian Army, and Ali Kuli Khan of Pakistan Army.[41] In his course studies, Musharraf performed extremely in relation to his classmates, submitted his master's degree thesis, titled "Impact of Arm Race in the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent", and earned good remarks.[41] He submitted his thesis to Commandant General Antony Walker who regarded Musharraf as one of his finest students he had seen in his entire career.[41] At one point, Walker described Musharraf: "A capable, articulate and extremely personable officer, who made a valuable impact at RCDS. His country is fortunate to have the services of a man of his undeniable quality."[41] He graduated with a master's degree from RCDS and returned to Pakistan soon after.[41] Upon returning in the 1980s, Musharraf took an interest in the emerging Pakistani rock music genre, and often listened to rock music after leaving duty.[15] During that decade, regarded as the time when rock music in Pakistan began, Musharraf was reportedly keen on the popular Western fashions of the time, which were then very popular in government and public circles.[15] While in the Army he earned the nickname "Cowboy" for his westernised ways and his fashion interest in Western clothing.[38][39]

Higher commands (1991–1995)

Earlier in 1988–89, as Brigadier, Musharraf proposed the Kargil infiltration to Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto but she rebuffed the plan.[42] In 1991–93, he secured a two-star promotion, elevating him to the rank of major general and held the command of 40th Division as its GOC, stationed in Okara Military District in Punjab Province.[41] In 1993–95, Major-General Musharraf worked closely with the Chief of Army Staff as Director-General of Pakistan Army's Directorate General for the Military Operations (DGMO).[39] During this time, Musharraf became close to engineering officer and director-general of ISI lieutenant-general Javed Nasir and had worked with him while directing operations in Bosnian war.[41][43] His political philosophy was influenced by Benazir Bhutto[44] who mentored him on various occasions, and Musharraf generally was close to Benazir Bhutto on military policy issues on India.[44] From 1993 to 1995, Musharraf repeatedly visited the United States as part of the delegation of Benazir Bhutto.[44] It was Maulana Fazal-ur-Rehman who lobbied for his promotion to Benazir Bhutto, and subsequently getting Musharraf's promotion papers approved by Benazir Bhutto, which eventually led to his appointment in Benazir Bhutto's key staff.[45] In 1993, Musharraf personally assisted Benazir Bhutto to have a secret meeting at the Pakistani embassy in Washington, D.C., with officials from the Mossad and a special envoy of Israeli premier Yitzhak Rabin.[44] It was during this time Musharraf built an extremely cordial relationship with Shaukat Aziz who, at that time, was serving as the executive president of global financial services of the Citibank.[44][46]

After the collapse of the fractious Afghan government, Musharraf assisted General Babar and the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) in devising a policy of supporting the newly formed Taliban in the Afghan civil war against the Northern Alliance government.[38] On policy issues, Musharraf befriended senior justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan Justice Rafiq Tarar (later president) and held common beliefs with the latter.[41]

His last military field operations posting was in the Mangla region of the Kashmir Province in 1995 when Benazir Bhutto approved the promotion of Musharraf to three-star rank, Lieutenant-General.[41] Between 1995 and 1998, Lieutenant-General Musharraf was the corps commander of I Strike Corps (CC-1) stationed in Mangla, Mangla Military District.[35]

Four-star appointments (1998–2007)

Chief of Army Staff and Chairman Joint Chiefs

There were three lieutenant-generals potentially in line to succeed General Jehangir Karamat as chief of army staff. Musharraf was third-in-line and was well regarded by the general public and the armed forces. He also had an excellent academic standing from his college and university studies.[45] Musharraf was strongly favoured by the Prime Minister's colleagues: a straight officer with democratic views.[45] Nisar Ali Khan and Shahbaz Sharif recommended Musharraf and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif personally promoted Musharraf to the rank of four-star general to replace Karamat.[35][47][48][46]

After the Kargil incident, Musharraf did not wish to be the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs:[45] Musharraf favoured the chief of naval staff Admiral Bokhari to take on this role, and claimed that: "he did not care"[45] Prime minister Sharif was displeased by this suggestion, due to the hostile nature of his relationship with the Admiral. Musharraf further exacerbated his divide with Nawaz Sharif after recommending the forced retirement of senior officers close to the Prime minister,[45] including Lieutenant-General Tariq Pervez (also known by his name's initials as TP), commander of XII Corps, who was a brother-in-law of a high profile cabinet minister.[45] According to Musharraf, lieutenant-general TP was an ill-mannered, foul-mouthed, ill-disciplined officer who caused a great deal of dissent within the armed forces.[45] Nawaz Sharif's announcement of the promotion of General Musharraf to Chairman Joint Chiefs caused an escalation of the tensions with Admiral Bokhari: upon hearing the news, he launched a strong protest against the Prime minister. The next morning, the Prime minister relieved Admiral Bokhari of his duties.[45] It was during his time as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs that Musharraf began to build friendly relations with the United States Army establishment, including General Anthony Zinni, USMC, General Tommy Franks, General John Abizaid, and General Colin Powell of the US Army, all of whom were premier four-star generals.[49]

Kargil Conflict

The Pakistan Army originally conceived the Kargil plan after the Siachen conflict but the plan was rebuffed repeatedly by senior civilian and military officials.[42] Musharraf was a leading strategist behind the Kargil Conflict.[23] From March to May 1999, he ordered secret infiltration of forces into the Kargil district.[38] After India discovered the infiltration, a fierce Indian offensive nearly led to a full-scale war.[38][42] However, Sharif withdrew support for the insurgents in July because of heightened international pressure.[38] Sharif's decision antagonised the Pakistan Army and rumours of a possible coup began emerging soon afterward.[38][50] Sharif and Musharraf dispute on who was responsible for the Kargil conflict and Pakistan's withdrawal.[51]

This strategic operation met with great hostility in the public circles and wide scale disapproval in the media who roundly criticised this operation.[52] Musharraf had severe confrontation and became involved in serious altercations with his senior officers, chief of naval staff Admiral Fasih Bokhari,[53] chief of air staff, Air Chief Marshal PQ Mehdi and senior lieutenant-general Ali Kuli Khan.[54] Admiral Bokhari ultimately demanded a full-fledged joint-service court martial against General Musharraf,[53] while on the other hand General Kuli Khan lambasted the war as "a disaster bigger than the East-Pakistan tragedy",[54] adding that the plan was "flawed in terms of its conception, tactical planning and execution" that ended in "sacrificing so many soldiers."[54][55] Problems with his lifelong friend, chief of air staff air chief marshal Pervez Mehdi also arose when air chief refrained to participate or authorise any air strike to support the elements of army operations in the Kargil region.[56]

During the last meeting with the Prime minister, Musharraf faced grave criticism on results produced by Kargil infiltration by the principal military intelligence (MI) director lieutenant-general Jamshed Gulzar Kiani who maintained in the meeting: "(...) whatever has been written there is against logic. If you catch your enemy by the jugular vein he would react with full force... If you cut enemy supply lines, the only option for him will be to ensure supplies by air... (sic).. at that situation the Indian Army was unlikely to confront and it had to come up to the occasion. It is against wisdom that you dictate to the enemy to keep the war limited to a certain front...."[57]

Nawaz Sharif has maintained that the Operation was conducted without his knowledge. However, details of the briefing he got from the military before and after the Kargil operation have become public. Before the operation, between January and March, Sharif was briefed about the operation in three separate meetings. In January, the army briefed him about the Indian troop movement along the LOC in Skardu on 29 January 1999, on 5 February at Kel, on 12 March at the GHQ, and finally on 17 May at the ISI headquarters. During the end of the June DCC meeting, a tense Sharif turned to the army chief and said "you should have told me earlier", Musharraf pulled out his notebook and repeated the dates and contents of around seven briefings he had given him since the beginning of January.[58]

Chief Executive (1999–2002)

1999 coup

Military officials from Musharraf's Joint Staff Headquarters (JS HQ) met with regional corps commanders three times in late September in anticipation of a possible coup.[59] To quieten rumours of a fallout between Musharraf and Sharif, Sharif officially certified Musharraf's remaining two years of his term on 30 September.[59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66]

Musharraf left for a weekend trip to take part in Sri Lanka's Army's 50th-anniversary celebrations.[67] When Pervez Musharraf was returning from his visit to Colombo his flight was denied landing permissions at Karachi International Airport on orders from the Prime Minister's office.[68] Upon hearing the announcement of Nawaz Sharif replacing Pervez Musharraf with Khwaja Ziauddin, the third replacement of the top military commander of the country in less than two years,[68] local military commanders began to mobilise troops towards Islamabad from nearby Rawalpindi.[67][68] The military placed Sharif under house arrest,[69] but in a last-ditch effort Sharif privately ordered Karachi air traffic controllers to redirect Musharraf's flight to India.[59][68] The plan failed after soldiers in Karachi surrounded the airport control tower.[68][70] At 2:50 am on 13 October,[69] Musharraf addressed the nation with a recorded message.[68]

Musharraf met with President Rafiq Tarar on 13 October to deliberate on legitimising the coup.[71] On 15 October, Musharraf ended emerging hopes of a quick transition to democracy after he declared a state of emergency, suspended the Constitution and assumed power as Chief Executive.[70][72] He also quickly purged the government of political enemies, notably Ziauddin and national airline chief Shahid Khaqan Abbassi.[70] On 17 October, he gave his second national address and established a seven-member military-civilian council to govern the country.[73][74] He named three retired military officers and a judge as provincial administrators on 21 October.[75] Ultimately, Musharraf assumed executive powers but did not obtain the office of the Prime minister.[74] The Prime minister's secretariat (official residence of Prime minister of Pakistan) was closed by the military police and its staff was fired by Musharraf immediately.[74]

There were no organised protests within the country to the coup,[74][76] that was widely criticised by the international community.[77] Consequently, Pakistan was suspended from the Commonwealth of Nations.[78][79] Sharif was put under house arrest and later exiled to Saudi Arabia on his personal request and under a contract.[80]

First days

The senior military appointments in the inter-services were extremely important and crucial for Musharraf to keep the legitimacy and the support for his coup in the joint inter-services.[81] Starting with the PAF, Musharraf pressured President Tarar to appoint most-junior air marshal to four-star rank, particularly someone with Musharraf had experienced working during the inter-services operations.[56] Once Air-chief Marshal Pervez Kureshi was retired, the most junior air marshal Muschaf Mir (who worked with Musharraf in 1996 to assist ISI in Taliban matters) was appointed to four-star rank as well as elevated as Chief of Air Staff.[56] There were two extremely important military appointments made by Musharraf in the Navy. Although Admiral Aziz Mirza (a lifelong friend of Musharraf, he shared a dorm with the admiral in the 1960s and they graduated together from the academy) was appointed by Prime minister Nawaz Sharif, Mirza remained extremely supportive of Musharraf's coup and was also a close friend of Musharraf since 1971 when both participated in a joint operation against the Indian Army.[81] After Mirza's retirement, Musharraf appointed Admiral Shahid Karimullah, with whom Musharraf had trained together in special forces schools during the 1960s,[81] to four-star rank and chief of naval staff.[82]

Musharraf's first foreign visit was to Saudi Arabia on 26 October where he met with King Fahd.[83][84] After meeting senior Saudi royals, the next day he went to Medina and performed Umrah in Mecca.[83] On 28 October, he went to the United Arab Emirates before returning home.[83][84]

By the end of October, Musharraf appointed many technocrats and bureaucrats in his Cabinet, including former Citibank executive Shaukat Aziz as Finance Minister and Abdul Sattar as Foreign Minister.[85][86] In early November, he released details of his assets to the public.[87]

In late December 1999, Musharraf dealt with his first international crisis when India accused Pakistan's involvement in the Indian Airlines Flight 814 hijacking.[88][89] Though United States president Bill Clinton pressured Musharraf to ban the alleged group behind the hijacking — Harkat-ul-Mujahideen,[90] Pakistani officials refused because of fears of reprisal from political parties such as Jamaat-e-Islami.[91]

In March 2000, Musharraf banned political rallies.[76] In a television interview given in 2001, Musharraf openly spoke about the negative role of a few high-ranking officers in the Pakistan Armed Forces in state's affairs.[92] Musharraf labelled many of his senior professors at NDU as "pseudo-intellectuals", including the NDU's notable professors, General Aslam Beg and Jehangir Karamat under whom Musharraf studied and served well.[92]

Sharif trial and exile

The Military Police held former prime minister Sharif under house arrest at a government guesthouse[93] and opened his Lahore home to the public in late October 1999.[85] He was formally indicted in November[93] on charges of hijacking, kidnapping, attempted murder, and treason for preventing Musharraf's flight from landing at Karachi airport on the day of the coup.[94][95] His trial began in early March 2000 in an anti-terrorism court,[96] which is designed for speedy trials.[97] He testified Musharraf began preparations of a coup after the Kargil conflict.[96] Sharif was placed in Adiala Jail, infamous for hosting Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's trial, and his leading defence lawyer, Iqbal Raad, was shot dead in Karachi in mid-March.[98] Sharif's defence team blamed the military for intentionally providing their lawyers with inadequate protection.[98] The court proceedings were widely accused of being a show trial.[99][100][101] Sources from Pakistan claimed that Musharraf and his military government's officers were in full mood to exercise tough conditions on Sharif, and intended to send Nawaz Sharif to the gallows to face a similar fate to that of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1979. It was the pressure on Musharraf exerted by Saudi Arabia and the United States to exile Sharif after it was confirmed that the court is about to give its verdict on Nawaz Sharif over treason charges, and the court would sentence Sharif to death. Sharif signed an agreement with Musharraf and his military government and his family was exiled to Saudi Arabia in December 2000.[102]

Constitutional changes

Shortly after Musharraf's takeover, Musharraf issued Oath of Judges Order No. 2000, which required judges to take a fresh oath of office.[103] On 12 May 2000, the Supreme Court asked Musharraf to hold national elections by 12 October 2002.[104] After President Rafiq Tarar's resignation, Musharraf formally appointed himself as President on 20 June 2001.[105] In August 2002, he issued the Legal Framework Order No. 2002, which added numerous amendments to the Constitution.[106]

2002 general elections

Musharraf called for nationwide political elections in the country after accepting the ruling of the Supreme Court of Pakistan.[15] Musharraf was the first military president to accept the rulings of the Supreme Court and holding free and fair elections in 2002, part of his vision to return democratic rule to the country.[15] In October 2002, Pakistan held general elections, which the pro-Musharraf PML-Q won wide margins, although it had failed to gain an absolute majority. The PML-Q formed a government with far-right religious parties coalition, the MMA and the liberals MQM; the coalition legitimised Musharraf's rule.[15]

After the elections, the PML-Q nominated Zafarullah Khan Jamali for the office of prime minister, which Musharraf also approved.[107] After first session at the Parliament, Musharraf voluntarily transferred the powers of chief executive to Prime Minister Zafarullah Khan Jamali.[15] Musharraf succeeded to pass the XVII amendment, which grants powers to dissolve the parliament, with approval required from the Supreme Court.[15] Within two years, Jamali proved to be an ineffective prime minister as he forcefully implemented his policies in the country and caused problems with the business class elites. Musharraf accepted the resignation of Jamali and asked his close colleague Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain to appoint a new prime minister in place.[15] Hussain nominated Finance minister Shaukat Aziz, who had been impressive due to his performance as finance minister in 1999. Musharraf regarded Aziz as his right hand and preferable choice for the office of Prime minister.[15] With Aziz appointed as Prime minister, Musharraf transferred all executive powers to Aziz as he trusted Shaukat Aziz.[15] Aziz proved to be extremely capable in running the government; under his leadership economic growth reached to a maximum level, which further stabilised Musharraf's presidency.[108] Aziz swiftly, quietly and quickly undermined the elements seeking to undermine Musharraf, which became a factor in Musharraf's trust in him.[108] Between 2004 and 2007, Aziz approved many projects that did not require Musharraf's permission.[108]

In 2010, all constitutional changes carried out by Musharraf and Aziz's policies were reverted by the 18th Amendment, which restored the powers of the Prime Minister and reduced the role of the President to levels below that of even the pre-Musharraf era.[109][110]

He suspended the country's democratic process and imposed two states of emergency, leading to his conviction for treason. During his rule, he implemented both liberal reforms and authoritarian measures, while also forming alliances and impacting the situation in Balochistan. The legacy of Musharraf's era serves as a cautionary tale for future leaders in Pakistan.[111]

Presidency (2001–2008)

The President [Musharraf] stood clapping his hands right next to us as we sang Azadi and Jazba, and moved to the beat with us. It was such a relief to "have a coolest leader" in the office...

The presidency of Pervez Musharraf helped bring the liberal forces to the national level and into prominence, for the first time in the history of Pakistan.[15] He granted national amnesty to the political workers of the liberal parties like Muttahida Qaumi Movement and Pakistan Muslim League (Q), and supported MQM in becoming a central player in the government. Musharraf disbanded the cultural policies of the previous Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, and quickly adopted Benazir Bhutto's cultural policies after disbanding Indian channels in the country.[15]

His cultural policies liberalised Pakistan's media, and he issued many television licences to the private-sector to open television centres and media houses.[15] The television dramas, film industry, theatre, music and literature activities, were personally encouraged by Pervez Musharraf.[15] Under his policies, the rock music bands gained a following in the country and many concerts were held each week.[15] His cultural policies, the film, theatre, rock and folk music, and television programs were extremely devoted to and promoted the national spirit of the country.[15] In 2001, Musharraf got on stage with the rock music band, Junoon, and sang the national song with the band.[113]

On political fronts, Musharraf faced fierce opposition from the ultra-conservative alliance, the MMA, led by clergyman Maulana Noorani.[45] In Pakistan, Maulana Noorani was remembered as a mystic religious leader and had preached spiritual aspects of Islam all over the world as part of the World Islamic Mission.[45] Although the political deadlock posed by Maulana Noorani was neutralised after Noorani's death, Musharraf yet had to face the opposition from ARD led by Benazir Bhutto of the PPP.[45]

On 18 September 2005, Musharraf made a speech before a broad based audience of Jewish leadership, sponsored by the American Jewish Congress's Council for World Jewry, in New York City. He was widely criticised by Middle Eastern leaders, but was met with some praise among Jewish leadership.[114]

Support for the war on terror and Afghanistan relations

Musharraf allied with the United States against the Taliban in Afghanistan after the September 11 attacks.[113] As the closest state to the Taliban government, Musharraf was in negotiations with them in the aftermath of the attacks regarding the severity of the situation[115] before allying with the U.S. and declaring to stamp out extremism.[116] He was, however criticised by NATO and the Afghan government of not doing enough to prevent pro Taliban or al-Qaeda militants in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border region.[117][118][119][120][121][46]

Tensions with Afghanistan increased in 2006, with Hamid Karzai, then president of Afghanistan, accusing Musharraf of failing to act against Afghan Taliban leaders in Pakistan, claiming that the Taliban leader Mullah Omar was based in Quetta, Pakistan. In response, Musharraf hit back saying "None of this is true and Karzai knows it."[122] George W. Bush encouraged the two leaders to unite in the war on terror during a trio meeting.[123]

Violence in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa escalated in the late 2000s amid fighting between militants and Pakistani soldiers backed by the U.S.[124]

Relations with India

After the 2001 Gujarat earthquake, Musharraf expressed his sympathies to Indian prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and sent a plane load of relief supplies to India.[125][126][127]

In 2004, Musharraf began a series of talks with India to resolve the Kashmir dispute.[128] In 2004 a cease-fire was agreed upon along the Line of Control. Many troops still patrol the border.[129]

Relations with Saudi Arabia

In 2006, King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia visited Pakistan for the first time as King. Musharraf honoured King Abdullah with the Nishan-e-Pakistan.[130] Musharraf received the King Abdul-Aziz Medallion in 2007.[131]

Nuclear scandals

From September 2001 until his resignation in 2007 from the military, Musharraf's presidency was affected by scandals relating to nuclear weapons, which were detrimental to his authoritative legitimacy in the country and in the international community.[132] In October 2001, Musharraf authorised a sting operation led by FIA to arrest two physicists Sultan Bashiruddin Mahmood and Chaudhry Abdul Majeed, because of their supposed connection with the Taliban after they secretly visited Taliban-controlled Afghanistan in 2000.[133] The local Pakistani media widely circulated the reports that "Mahmood had a meeting with Osama bin Laden where Bin Laden had shown interest in building a radiological weapon;"[133] it was later discovered that neither scientist had any in-depth knowledge of the technology.[133][134] In December 2001, Musharraf authorised security hearings and the two scientists were taken into the custody by the JAG Branch (JAG); security hearings continued until early 2002.[133]

Another scandal arose as a consequence of disclosure by Pakistani nuclear physicist Abdul Qadeer Khan. On 27 February 2001, Musharraf spoke highly of Khan at a state dinner in Islamabad,[135] and he personally approved Khan's appointment as Science Advisor to the Government. In 2004, Musharraf relieved Abdul Qadeer Khan from his post and initially denied knowledge of the government's involvement in nuclear proliferation, despite Khan's claim that Musharraf was the "Big Boss" of the proliferation ring. Following this, Musharraf authorised a national security hearing, which continued until his resignation from the army in 2007. According to Zahid Malik, Musharraf and the military establishment at that time acted against Abdul Qadeer Khan in an attempt to prove the loyalty of Pakistan to the United States and Western world.[136][137]

The investigations backfired on Musharraf and public opinion turned against him.[138] The populist ARD movement, which included the major political parties such as the PML and the PPP, used the issue to bring down Musharraf's presidency.[139]

The debriefing of Abdul Qadeer Khan severely damaged Musharraf's own public image and his political prestige in the country.[139] He faced bitter domestic criticism for attempting to vilify Khan, specifically from opposition leader Benazir Bhutto. In an interview to Daily Times, Bhutto maintained that Khan had been a "scapegoat" in the nuclear proliferation scandal and said that she did not "believe that such a big scandal could have taken place under the nose of General Musharraf".[140] Musharraf's long-standing ally, the MQM, published criticism of Musharraf over his handling of Abdul Qadeer Khan. The ARD movement and the political parties further tapped into the public anger and mass demonstrations against Musharraf. The credibility of the United States was also badly damaged;[139] the US itself refrained from pressuring Musharraf to take further action against Khan.[141] While Abdul Qadeer Khan remained popular in the country,[142][143] Musharraf could not withstand the political pressure and his presidency was further weakened.[140] Musharraf quickly pardoned Abdul Qadeer Khan in exchange for cooperation and issued confinement orders against Khan that limited Khan's movement.[144] He handed over the case of Abdul Qadeer Khan to Prime minister Aziz who had been supportive towards Khan, personally "thanking" him: "The services of Dr. Qadeer Khan are unforgettable for the country."[145]

On 4 July 2008, in an interview, Abdul Qadeer Khan laid the blame on President Musharraf and later on Benazir Bhutto for transferring the technology, claiming that Musharraf was aware of all the deals and he was the "Big Boss" for those deals.[146] Khan said that "Musharraf gave centrifuges to North Korea in a 2000 shipment supervised by the armed forces. The equipment was sent in a North Korean plane loaded under the supervision of Pakistan security officials."[146] Nuclear weapons expert David Albright of the Institute for Science and International Security agreed that Khan's activities were government-sanctioned.[147] After Musharraf's resignation, Abdul Qadeer Khan was released from house arrest by the executive order of the Supreme Court of Pakistan. After Musharraf left the country, the new Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee General Tärik Majid terminated all further debriefings of Abdul Qadeer Khan. Few believed that Abdul Qadeer Khan acted alone and the affair risked gravely damaging the Armed Forces, which oversaw and controlled the nuclear weapons development and of which Musharraf was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff until his resignation from military service on 28 November 2007.[132]

Corruption issues

When Musharraf came to power in 1999, he promised that the corruption in the government bureaucracy would be cleaned up. However, some claimed that the level of corruption did not diminish throughout Musharraf's time.[148]

Domestic politics

Musharraf instituted prohibitions on foreign students' access to studying Islam within Pakistan, an effort that began as an outright ban but was later reduced to restrictions on obtaining visas.[149]

In December 2003, Musharraf made a deal with MMA, a six-member coalition of hardline Islamist parties, agreeing to leave the army by 31 December 2004.[150][151] With that party's support, pro-Musharraf legislators were able to muster the two-thirds supermajority required to pass the Seventeenth Amendment, which retroactively legalised Musharraf's 1999 coup and many of his decrees.[152][153] Musharraf reneged on his agreement with the MMA[153] and pro-Musharraf legislators in the Parliament passed a bill allowing Musharraf to keep both offices.[154]

On 1 January 2004, Musharraf had won a confidence vote in the Electoral College of Pakistan, consisting of both houses of Parliament and the four provincial assemblies. Musharraf received 658 out of 1170 votes, a 56% majority, but many opposition and Islamic members of parliament walked out to protest the vote. As a result of this vote, his term was extended to 2007.[152]

Prime Minister Zafarullah Khan Jamali resigned on 26 June 2004, after losing the support of Musharraf's party, PML(Q). His resignation was at least partially due to his public differences with the party chairman, Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain. This was rumoured to have happened at Musharraf's command. Jamali had been appointed with the support of Musharraf's and the pro-Musharraf PML(Q). Most PML(Q) parliamentarians formerly belonged to the Pakistan Muslim League party led by Sharif, and most ministers of the cabinet were formerly senior members of other parties, joining the PML(Q) after the elections upon being offered positions. Musharraf nominated Shaukat Aziz, the minister for finance and a former employee of Citibank and head of Citibank Private Banking as the new prime minister.[155]

In 2005, the Bugti clan attacked a gas field in Balochistan, after Dr. Shazia was raped at that location. Musharraf responded by dispatching 4,500 soldiers, supported by tanks and helicopters, to guard the gas field.[156]

Women's rights

The National Assembly voted in favour of the "Women's Protection Bill" on 15 November 2006 and the Senate approved it on 23 November 2006. President General Pervez Musharraf signed into law the "Women's Protection Bill", on 1 December 2006. The bill places rape laws under the penal code and allegedly does away with harsh conditions that previously required victims to produce four male witnesses and exposed the victims to prosecution for adultery if they were unable to prove the crime.[157] However, the Women's Protection bill has been criticised heavily by many for paying continued lip service and failing to address the actual problem by its roots: repealing the Hudood Ordinance. In this context, Musharraf has also been criticised by women and human rights activists for not following up his words by action.[158][159] The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) said that "The so-called Women's Protection Bill is a farcical attempt at making Hudood Ordinances palatable" outlining the issues of the bill and the continued impact on women.[160]

His government increased reserved seats for women in assemblies, to increase women's representation and make their presence more effective. The number of reserved seats in the National Assembly was increased from 20 to 60. In provincial assemblies, 128 seats were reserved for women. This situation has brought out increase participation of women in the 1988 and 2008 elections.[161]

In March 2005, a couple of months after the rape of a Pakistani physician, Dr. Shazia Khalid, working on a government gas plant in the remote Balochistan province, Musharraf was criticised for pronouncing Captain Hammad, a fellow military man and the accused in the case, innocent before the judicial inquiry was complete.[162][163] Shazia alleged that she was forced by the government to leave the country.[164]

In an interview given to The Washington Post in September 2005, Musharraf said that Pakistani women who had been the victims of rape treated rape as a "moneymaking concern", and were only interested in the publicity to make money and get a Canadian visa. He subsequently denied making these comments, but the Post made available an audio recording of the interview, in which Musharraf could be heard making the quoted remarks.[165] Musharraf also denied Mukhtaran Mai, a Pakistani rape victim, the right to travel abroad, until pressured by US State Department.[166] The remarks made by Musharraf sparked outrage and protests both internationally and in Pakistan by various groups i.e. women groups, activists.[167] In a rally, held close to the presidential palace and Pakistan's parliament, hundreds of women demonstrated in Pakistan demanding Musharraf apologise for the controversial remarks about female rape victims.[168]

Assassination attempts

Musharraf survived multiple assassination attempts and alleged plots.[169][170] In 2000 Kamran Atif, an alleged member of Harkat-ul Mujahideen al-Alami, tried to assassinate Musharraf. Atif was sentenced to death in 2006 by an Anti Terrorism Court.[171] On 14 December 2003, Musharraf survived an assassination attempt when a powerful bomb went off minutes after his highly guarded convoy crossed a bridge in Rawalpindi; it was the third such attempt during his four-year rule. On 25 December 2003, two suicide bombers tried to assassinate Musharraf, but their car bombs failed to kill him; 16 others died instead.[172] Musharraf escaped with only a cracked windshield on his car.[169] Amjad Farooqi was an alleged mastermind behind these attempts, and was killed by Pakistani forces in 2004 after an extensive manhunt.[173][174]

On 6 July 2007, there was another attempted assassination, when an unknown group fired a 7.62 submachine gun at Musharraf's plane as it took off from a runway in Rawalpindi. Security also recovered two anti-aircraft guns, from which no shots had been fired.[175] On 17 July 2007, Pakistani police detained 39 people in relation to the attempted assassination of Musharraf.[176] The suspects were detained at an undisclosed location by a joint team of Punjab Police, the Federal Investigation Agency and other Pakistani intelligence agencies.[177]

Fall from the presidency

By August 2007, polls showed 64 per cent of Pakistanis did not want another Musharraf term.[178][179][180][46] Controversies involving the atomic issues, Lal Masjid incident, the unpopular War in North-West Pakistan, the suspension of Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, and widely circulated criticisms from rivals Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif, had brutalised the personal image of Musharraf in public and political circles. More importantly, with Shaukat Aziz departing from the office of Prime Minister, Musharraf could not have sustained his presidency any longer and dramatically fell from the presidency within a matter of eight months, after popular and mass public movements called for his impeachment for the actions taken during his presidency.[181][182]

Suspension of the Chief Justice

On 9 March 2007, Musharraf suspended Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry and pressed corruption charges against him. He replaced him with Acting Chief Justice Javed Iqbal.[183]

Musharraf's moves sparked protests among Pakistani lawyers. On 12 March 2007, lawyers started a campaign called Judicial Activism across Pakistan and began boycotting all court procedures in protest against the suspension. In Islamabad, as well as other cities such as Lahore, Karachi, and Quetta hundreds of lawyers dressed in black suits attended rallies, condemning the suspension as unconstitutional. Slowly the expressions of support for the ousted Chief Justice gathered momentum and by May, protesters and opposition parties took out huge rallies against Musharraf, and his tenure as army chief was also challenged in the courts.[184][185]

Lal Masjid siege

The Lal Masjid mosque in Islamabad had a religious school for women and the Jamia Hafsa madrassa, which was attached to the mosque.[186] A male madrassa was only a few minutes drive away.[186] In April 2007, the mosque administration started to encourage attacks on local video shops, alleging that they were selling porn films; and massage parlours, which were alleged to be used as brothels. These attacks were often carried out by the mosque's female students. In July 2007, a confrontation occurred when government authorities made a decision to stop the student violence and send police officers to arrest the responsible individuals and the madrassa administration.[187]

This development led to a standoff between police forces and armed students.[188] Mosque leaders and students refused to surrender and fired at police from inside the mosque building. Both sides suffered casualties.[189]

Return of Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif

On 27 July, Bhutto met for the first time with Musharraf in the UAE to discuss her return to Pakistan.[190] On 14 September 2007, Deputy Information Minister Tariq Azim stated that Bhutto will not be deported, but must face corruption charges against her. He clarified Sharif's and Bhutto's right to return to Pakistan.[191] On 17 September 2007, Bhutto accused Musharraf's allies of pushing Pakistan to crisis by refusal to restore democracy and share power. Bhutto returned from eight years exile on 18 October.[192] Musharraf called for a three-day mourning period after Bhutto's assassination on 27 December 2007.[193]

Sharif returned to Pakistan in September 2007 and was immediately arrested and taken into custody at the airport. He was sent back to Saudi Arabia.[194] Saudi intelligence chief Muqrin bin Abdul-Aziz Al Saud and Lebanese politician Saad Hariri arrived separately in Islamabad on 8 September 2007, the former with a message from Saudi King Abdullah and the latter after a meeting with Nawaz Sharif in London. After meeting President General Pervez Musharraf for two-and-a-half hours discussing Nawaz Sharif's possible return.[195] On arrival in Saudi Arabia, Nawaz Sharif was received by Prince Muqrin bin Abdul-Aziz, the Saudi intelligence chief, who had met Musharraf in Islamabad the previous day. That meeting had been followed by a rare press conference, at which he had warned that Sharif should not violate the terms of King Abdullah's agreement of staying out of politics for 10 years.[196]

Resignation from the Military

On 2 October 2007, Musharraf appointed General Tariq Majid as Chairman Joint Chiefs Committee and approved General Ashfaq Kayani as vice chief of the army starting 8 October. When Musharraf resigned from military on 28 November 2007, Kayani became Chief of Army Staff.[197]

2007 presidential elections

In a March 2007 interview, Musharraf said that he intended to stay in office for another five years.[198]

A nine-member panel of Supreme Court judges deliberated on six petitions (including Jamaat-e-Islami's, Pakistan's largest Islamic group) for disqualification of Musharraf as a presidential candidate.[199] Bhutto stated that her party may join other opposition groups, including Sharif's.[200]

On 28 September 2007, in a 6–3 vote, Judge Rana Bhagwandas's court removed obstacles to Musharraf's election bid.[201]

2007 state of emergency

On 3 November 2007, Musharraf declared emergency rule across Pakistan.[202][203] He suspended the Constitution, imposed a state of emergency, and fired the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court again.[204] In Islamabad, troops entered the Supreme Court building, arrested the judges and kept them detained in their homes.[203] Independent and international television channels went off air.[204] Public protests were mounted against Musharraf.[205]

2008 general elections

General elections were held on 18 February 2008, in which the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) polled the highest votes and won the most seats.[206][207] On 23 March 2008, President Musharraf said an "era of democracy" had begun in Pakistan and that he had put the country "on the track of development and progress". On 22 March, the PPP named former parliament speaker Yusuf Raza Gilani as its candidate for the country's next prime minister, to lead a coalition government united against him.[208]

Impeachment movement

On 7 August 2008, the Pakistan Peoples Party and the Pakistan Muslim League (N) agreed to force Musharraf to step down and begin his impeachment. Asif Ali Zardari and Nawaz Sharif announced sending a formal request or joint charge sheet that he step down, and impeach him through parliamentary process upon refusal. Musharraf refused to step down.[209] A charge-sheet had been drafted and was to be presented to parliament. It included Mr. Musharraf's first seizure of power in 1999—at the expense of Nawaz Sharif, the PML(N)'s leader, whom Mr. Musharraf imprisoned and exiled—and his second in November 2007, when he declared an emergency as a means to get re-elected as president. The charge-sheet also listed some of Mr. Musharraf's contributions to the "war on terror".[210]

Musharraf delayed his departure for the Beijing Olympics, by a day.[211][212] On 11 August, the government summoned the national assembly.[213]

Exile

On 18 August 2008, Musharraf announced his resignation. On the following day, he defended his nine-year rule in an hour-long televised speech.[214][215] However, public opinion was largely against him by this time. A poll conducted a day after his resignation showed that 63% of Pakistanis welcomed Musharraf's decision to step down while only 15% were unhappy with it.[216] On 23 November 2008 he left for exile in London where he arrived the following day.[217][218][219][220][221]

Academia and lectureship

After his resignation, Musharraf went to perform a holy pilgrimage to Mecca. He then went on a speaking and lectureship tour through the Middle East, Europe, and the United States. Chicago-based Embark LLC was one of the international public-relations firms trying to land Musharraf as a highly paid keynote speaker.[222] According to Embark President David B. Wheeler, the speaking fee for Musharraf would be US$150,000–200,000 for a day plus jet and other V.I.P. arrangements on the ground.[222] In 2011, he also lectured at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace on politics and racism where he also authored and published a paper with George Perkvich.[223]

Party creation

Musharraf launched his own political party, the All Pakistan Muslim League, in June 2010.[224][225][226][227]

Legal threats and actions

The PML-N tried to get Pervez Musharraf to stand trial under Article 6 of the Constitution for treason in relation to the emergency on 3 November 2007.[228] The Prime Minister of Pakistan Yousaf Raza Gilani has said a consensus resolution is required in national assembly for an article 6 trial of Pervez Musharraf[229]"I have no love lost for Musharraf ... if parliament decides to try him, I will be with parliament. Article 6 cannot be applied to one individual ... those who supported him are today in my cabinet and some of them have also joined the PML-N ... the MMA, the MQM and the PML-Q supported him ... this is why I have said that it is not doable," said the Prime Minister while informally talking to editors and also replying to questions by journalists at an Iftar-dinner he had hosted for them.[230] Although the constitution of Pakistan, Article 232 and Article 236, provides for emergencies,[231] and on 15 February 2008, the interim Pakistan Supreme Court attempted to validated the Proclamation of Emergency on 3 November 2007, the Provisional Constitution Order No 1 of 2007 and the Oath of Office (Judges) Order, 2007,[232] after the Supreme Court judges were restored to the bench,[233] on 31 July 2009, they ruled that Musharraf had violated the constitution when he declared emergency rule in 2007.[234][235]

Saudi Arabia exerted its influence to attempt to prevent treason charges, under Article 6 of the constitution, from being brought against Musharraf, citing existing agreements between the states,[236][237] as well as pressuring Sharif directly.[238] As it turned out, it was not Sharif's decision to make.[239]

Abbottabad's district and sessions judge in a missing person's case passed judgment asking the authorities to declare Pervez Musharraf a proclaimed offender.[240] On 11 February 2011 the Anti Terrorism Court,[241] issued an arrest warrant for Musharraf and charged him with conspiracy to commit murder of Benazir Bhutto.[242][243] On 8 March 2011, the Sindh High Court registered treason charges against him.[239][244][245][246]

Views

Pakistani police commandos

Regarding the Lahore attack on Sri Lankan cricket players, Musharraf criticised the police commandos' inability to kill any of the gunmen, saying "If this was the elite force I would expect them to have shot down those people who attacked them, the reaction, their training should be on a level that if anyone shoots toward the company they are guarding, in less than three seconds they should shoot the man down."[247][248]

Blasphemy laws

Regarding the blasphemy laws, Musharraf said that Pakistan is sensitive to religious issues and that the blasphemy law should stay.[249]

Return to Pakistan

Since the start of 2011, news had circulated that Musharraf would return to Pakistan before the 2013 general election. He himself vowed this in several interviews. On Piers Morgan Tonight, Musharraf announced his plans to return to Pakistan on 23 March 2012 to seek the Presidency in 2013.[250] The Pakistani Taliban[251] and Talal Bugti[252] threatened to kill him should he return.[253][254] On 24 March 2013, after a four-year self-imposed exile, he returned to Pakistan.[251][252] He landed at Jinnah International Airport, Karachi, via a chartered Emirates flight with Pakistani journalists and foreign news correspondents. Hundreds of his supporters and workers of APML greeted Musharraf upon his arrival at Karachi airport, and he delivered a short public speech.[255]

Electoral disqualification

On 16 April 2013, three weeks after he returned to Pakistan, an electoral tribunal in Chitral declared Musharraf disqualified from contesting elections, effectively quashing his political ambitions (several other constituencies had previously rejected Musharraf's nominations).[256] A spokesperson for Musharraf's party said the ruling was "biased" and they would appeal the decision.[218]

Jail, house arrest and bail

Two days later, on 18 April 2013, the Islamabad High Court ordered the arrest of Musharraf on charges relating to the 2007 arrests of judges.[257] Musharraf had technically been on bail since his return to the country, and the court now declared his bail ended.[258] Musharraf escaped from court with the aid of his security personnel, and went to his farm-house mansion.[259] The following day, Musharraf was placed under house arrest[260] but was later transferred to police headquarters in Islamabad.[261] Musharraf characterised his arrest as "politically motivated"[262][263] and his legal team has declared their intention to fight the charges in the Supreme Court.[261] Further to the charges of this arrest, the Senate also passed a resolution petitioning that Musharraf be charged with high treason in relation to the events of 2007.[261]

On Friday, 26 April 2013, a week after one court had voided his bail and caused his arrest in the "arrest of judges" case, another court ordered house arrest for Musharraf in connection with the death of Benazir Bhutto.[264] On 20 May, a Pakistani court granted bail to Musharraf.[265] On 12 June 2014 Sindh High Court allowed him to travel to seek medical attention abroad.[266][267]

Fourth assassination attempt

On 3 April 2014, Musharraf escaped the fourth assassination attempt, resulting in an injury of a woman, according to Pakistani news.[268]

Judicial hearings and return to exile

On 25 June 2013, Musharraf was named as prime suspect in two separate cases. The first case was subverting and suspending the constitution, and the second was a Federal Investigation Agency probe into the conspiracy to assassinate Bhutto.[269] Musharraf was indicted on 20 August 2013 for Bhutto's assassination in 2007.[270] On 2 September 2013, a first information report (FIR) was registered against him for his role in the Lal Masjid Operation in 2007. The FIR was lodged after the son of slain hard line cleric Abdul Rahid Ghazi (who was killed during the operation) asked authorities to bring charges against Musharraf.[271][272]

On 18 March 2016, Musharraf's name was removed from the Exit Control List and he was allowed to travel abroad, citing medical treatment. He subsequently lived in Dubai in self-imposed exile.[273][274] Musharraf vowed to return to Pakistan, but he never did.[275] It was first disclosed in October 2018 that Musharraf was suffering from amyloidosis, a rare and serious illness for which he has undergone treatment in hospitals in London and Dubai; an official with Musharraf's political party said that Musharraf would return to Pakistan after he made a full recovery.[276]

In 2017, Musharraf appeared as a political analyst on his weekly television show Sab Se Pehle Pakistan with President Musharraf, hosted by BOL News.[277]

On 31 August 2017, the anti-terrorism court in Rawalpindi declared him an "absconder" in Bhutto's murder case. The court also ordered that his property and bank account in Pakistan be seized.[244][278][279]

Verdict

On 17 December 2019, a special court declared him a traitor and sentenced him in absentia to death for abrogating and suspending the constitution in November 2007.[280][281][282][283][284] The three-member panel of the special court which issued the order was spearheaded by Chief Justice of the Peshawar High Court Waqar Ahmed Seth.[285] He was the first Pakistani Army General to be sentenced to death.[286][287] Analysts did not expect Musharraf to face the sentence given his illness and the fact that Dubai has no extradition treaty with Pakistan;[267][288] the verdict was also viewed as largely symbolic given that Musharraf retained support within the current Pakistani government and military.[275]

Musharraf challenged the verdict,[275][289][290] and on 13 January 2020, the Lahore High Court annulled the death sentence against Musharraf, ruling that the special court that held the trial was unconstitutional.[275] The unanimous verdict was delivered by a three-member bench of the Lahore High Court,[275][289] consisting of Justice Sayyed Muhammad Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqvi, Justice Muhammad Ameer Bhatti, and Justice Chaudhry Masood Jahangir.[289] The court ruled that the prosecution of Musharraf was politically motivated and that the crimes of high treason and subverting the Constitution were "a joint offence" that "cannot be undertaken by a single person."[275]

Personal life

Musharraf was the second son of his parents and had two brothers—Javed and Naved.[11][12][23] Javed retired as a high-level official in Pakistan's civil service.[23] Naved is an anaesthetist who has lived in Chicago since completing his residency training at Loyola University Medical Center in 1979.[11][23]

Musharraf married Sehba, who is from Karachi, on 28 December 1968.[22] They had a daughter, Ayla, an architect married to film director Asim Raza,[291] and a son, Bilal.[23][292] He also had close family ties to the prominent Kheshgi family.[293][294][295][296][297]

Death

On 5 February 2023, Musharraf died at age 79 due to amyloidosis.[298] He had been hospitalised a year prior due to the disease. His body was returned to Karachi, Pakistan, from Dubai on 6 February.[299] His funeral prayers were offered at a mosque in Karachi's Gulmohar Polo Ground in Malir Cantonment on 7 February.[300] He was laid to rest with military honours in an army graveyard.[301]

Bibliography

Musharraf published his autobiography—In the Line of Fire: A Memoir—in 2006.[302] His book has also been translated into Urdu, Hindi, Tamil and Bangali. In Urdu the title is Sab Se Pehle Pakistan (Pakistan Comes First).

Effective dates of promotion

| Insignia | Rank | Date |

|---|---|---|

| General, COAS | Oct 1998 | |

| Lieutenant-General | 1995 | |

| Major-General | 1991 | |

| Brigadier | 1987 | |

| Colonel | 1978 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | 1974 | |

| Major | 1972 | |

| Captain | 1966 | |

| Lieutenant | 1965 | |

| Second Lieutenant | 1964 |

Awards and decorations

| Nishan-e-Imtiaz

(Order of Excellence) |

Hilal-e-Imtiaz

(Crescent of Excellence) |

Tamgha-e-Basalat

(Medal of Good Conduct) |

Sitara-e-Harb 1965 War

(War Star 1965) |

| Sitara-e-Harb 1971 War

(War Star 1971) |

Tamgha-e-Jang 1965 War

(War Medal 1965) With MiD or Imtiazi Sanad |

Tamgha-e-Jang 1971 War

(War Medal 1971) |

Tamgha-e-Baqa

1998 |

| Tamgha-e-Istaqlal Pakistan

2002 |

10 Years Service Medal | 20 Years Service Medal | 30 Years Service Medal |

| 35 Years Service Medal | 40 Years Service Medal | Tamgha-e-Sad Saala Jashan-e-

(100th Birth Anniversary of 1976 |

Hijri Tamgha

(Hijri Medal) 1979 |

| Jamhuriat Tamgha

(Democracy Medal) 1988 |

Qarardad-e-Pakistan Tamgha

(Resolution Day Golden Jubilee Medal) 1990 |

Tamgha-e-Salgirah Pakistan

(Independence Day Golden Jubilee Medal) 1997 |

Command & Staff College |

Foreign decorations

| Foreign awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Order of King Abdul Aziz – Class I[131] | ||

| The Order of Zayed[303] | ||

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Boone, Jon (18 February 2014). "Pervez Musharraf makes first court appearance in treason case". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Pervez Musharraf: Pakistan ex-leader sentenced to death for treason". BBC News. 17 December 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Desk, BR Web (10 January 2024). "SC upholds Pervez Musharraf's death sentence in treason case". Brecorder. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Former military ruler Pervez Musharraf passes away in Dubai". DAWN.COM. Reuters. 5 February 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Dawn.com (5 February 2023). "Profile: Musharraf — from military strongman to forgotten man of politics". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Profile: Pervez Musharraf". BBC News. 16 June 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2009.

- ^ a b "India Remembers 'Baby Musharraf'". BBC News. 15 April 2005. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ a b c Dixit, Jyotindra Nath (2002). "Implications of the Kargil War". India-Pakistan in War & Peace (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 28–35. ISBN 978-0-415-30472-6.

- ^ a b c d Harmon, Daniel E. (13 October 2008). Pervez Musharraf: President of Pakistan (Easyread Super Large 20pt ed.). ReadHowYouWant.com. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4270-9203-8. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ Kashif, Imran (28 October 2014). "Musharraf's mother reaches Karachi". Karachi: Arynews. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Dugger, Celia W. (26 October 1999). "Pakistan Ruler Seen as 'Secular-Minded' Muslim". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Musharraf Mother Meets Indian PM" Archived 29 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News (21 March 2005).

- ^ "Gen Pervez Musharraf's mother dies in Dubai". 15 January 2021. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Worth, Richard; Kras, Sara Louise (2007). Pervez Musharraf. Infobase. ISBN 9781438104720. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Musharraf, Pervez (25 September 2006). In the Line of Fire: A Memoir (1 ed.). Pakistan: Free Press. pp. 40–60. ISBN 074-3283449. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Ajami, Fouad (15 June 2011). "Review: In the Line of Fire: A Memoir by Pervez Musharraf". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Rediff On The NeT: My brother, the general". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ a b Jacob, Satish (13 July 2001). "Musharraf's Family Links to Delhi". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ a b "Profile – Pervez Musharraf". BBC 4. 12 August 2003. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010.

- ^ Musharraf, Pervez (2006). In the Line of Fire: A Memoir. Simon & Schuster. p. 34. ISBN 9780743298438. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ a b c "Pakistan's Self-appointed Democratic Leader". CNN. 4 May 2003. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Worth, Richard. "Time of Trials". Pervez Musharraf. New York: Chelsea House, 2007. pp. 32–39 Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 1438104723

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Chitkara, M. G. "Pervez Bonaparte Musharraf Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine". Indo-Pak Relations: Challenges before New Millennium. New Delhi: A.P.H. Pub., 2001. pp. 135–36 ISBN 8176482722

- ^ a b c "FACTBOX – Facts about Pakistani Leader Pervez Musharraf" Archived 18 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Reuters (18 August 2008).

- ^ "CNN.com - General Pervez Musharraf, President and Chief Executive of Pakistan - June 28, 2001". CNN. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ Adil, Adnan. "Profile: Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain" Archived 12 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News (29 June 2004).

- ^ Musharraf Regime and Governance Crises. United States: Nova Science Publishers. p. 275. ISBN 1-59033-135-4. Retrieved 6 June 2012

- ^ "Q&A on What's Happening in Pakistan". MSNBC. 5 November 2007. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Tricks of the trade from a Sri Lankan general, and some secrets". 3 March 2013.

- ^ "The Sunday Times Front Section". sundaytimes.lk.

- ^ "Profile: Pervez Musharraf the cowboy who saved us". 25 February 2023.

- ^ "Meeting Sri Lanka's ex-army chief". The Express Tribune. 19 February 2013.

- ^ "Pervez Musharraf, an Adversary of the Eelam State – Ilankai Tamil Sangam". sangam.org.

- ^ "IF INDIA CAN'T, PAKISTAN MIGHT". Himal Southasian. 1 September 2000.

- ^ a b c d e f Crossette, Barbara. "Coup in Pakistan – Man in the News; A Soldier's Soldier, Not a Political General" Archived 28 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times (13 October 1999).

- ^ a b "Pakistan's Chief Executive a Former Commando" Archived 17 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine. New Straits Times (16 October 1999).

- ^ Schmetzer, Uli. "Coup Leader Is Hawkish Toward India" . Chicago Tribune. Battle of Asal Uttar (13 October 1999).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Weaver, Mary Anne. "General On Tightrope Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine". Pakistan: in the Shadow of Jihad and Afghanistan. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003. pp. 25–31 ISBN 0374528861

- ^ a b c Harmon, Daniel E. "A Nation Under Military Rule". Pervez Musharraf: President of Pakistan. New York: Rosen Pub., 2008. pp. 44–47 Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 1404219056

- ^ Musharraf, Pervez (2006). In the Line of Fire. Islamabad, Pakistan: Free Press. p. 79. ISBN 0-7432-8344-9. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k John, Wilson (2002). The General and Jihad (1 ed.). Washington D.C.: Pentagon Press. p. 45. ISBN 81-8274-158-0. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Kapur, S. Paul. "The Covert Nuclear Period". Dangerous Deterrent: Nuclear Weapons Proliferation and Conflict in South Asia. Singapore: NUS, 2009. pp. 117–18 Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 9971694433

- ^ Wilson John, pp209

- ^ a b c d e Journalist and author George Crile's book, Charlie Wilson's War: The Extraordinary Story of the Largest Covert Operation in History (Grove Press, New York, 2003)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hiro, Dilip (17 April 2012). Apocalyptic realm: jihadists in South Asia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 200–210. ISBN 978-0300173789. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Morris, Chris (18 August 2008). "Pervez Musharraf's mixed legacy". Special report published by Chris Morris BBC News, Islamabad. BBC News, Islamabad. BBC News, Islamabad. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Constable, Pamela (28 November 2007). "Musharraf Steps Down as Head of Pakistani Army". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "Pakistan's Dubious Referendum". The New York Times. 1 May 2002. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ Tony Zinni; Tom Clancy; Tony Koltz (2004). Battle ready (Berkley trade pbk. ed.). New York: Putnam. ISBN 0-399-15176-1.

- ^ "A Bleak Day for Pakistan". The Guardian. 13 October 1999. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Musharraf Vs. Sharif: Who's Lying?". The Weekly Voice. 2 October 2006. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

- ^

- Amir, Ayaz (9 July 1999). "Victory in reverse: the great climbdown". Dawn. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- Amir, Ayaz (23 July 1999). "For this submission what gain?". Dawn. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Musharraf planned coup much before Oct 12: Fasih Bokhari". Daily Times. Pakistan. 9 October 2002. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

Former Navy chief says the general feared court martial for masterminding Kargil

- ^ a b c Kargil was a bigger disaster than 1971 Archived 6 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine – Interview of Lt Gen Ali Kuli Khan Khattak.

- ^ Haleem, S. A. (19 October 2006). "Sweet and bitter memories (Review of In the Line of Fire by Pervez Musharraf)". Jang. Archived from the original on 24 November 2006.

- ^ a b c "Air Chief Marshal Parvaiz Mehdi Qureshi, NI(M), S Bt". PAF Directorate for Public Relations. PAF Gallery and Press Release. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ Masood, Shahid (3 June 2008). "Former general for making an example of Musharraf". GEO News Network. Archived from the original on 6 June 2008.

- ^ Zehra, Nasim (29 July 2004). "Nawaz Sharif Not A Kargil Victim". Media Monitors Network. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Weiner, Tim. "Countdown to Pakistan's Coup: A Duel of Nerves in the Air", The New York Times Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (17 October 1999).

- ^ Neilan, Terence (1 October 1999). "World Briefing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Wilson, John (2007). "General Pervez Musharraf— A Profile". The General and Jihad. Washington D.C.: Pentagon Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-520-24448-1.

- ^ Dummett, Mark (18 August 2008). "Pakistan's Musharraf steps down". Work and report completed by BBC correspondent for Pakistan Mark Dummett. BBC Pakistan, 2008. Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Rashid, Ahmed (2012). Pakistan in the Brink. Allen Lane. pp. 6, 21, 31, 35–38, 42, 52, 147, 165, 172, 185, 199, 205. ISBN 978-1-84614-585-8.

- ^ "Syed Pervez Musharraf kon hain ? | Daily Jang". jang.com.pk. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Pervez Musharraf Biography President (non-U.S.), General (1943–)". Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ "Pervez Musharraf: president of Pakistan". Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Under the Gun" Archived 18 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Time (25 October 1999).

- ^ a b c d e f "How the 1999 Pakistan Coup Unfolded" Archived 29 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News (23 August 2007).

- ^ a b Dugger, Celia W. "Coup in Pakistan: The Overview" Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times (13 October 1999)

- ^ a b c Dugger, Celia W., and Raja Zulfikar. "Pakistan Military Completes Seizure of All Authority" Archived 12 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times (15 October 1999)

- ^ Dugger, Celia W. "Pakistan Calm After Coup; Leading General Gives No Clue About How He Will Rule". The New York Times Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (14 October 1999).

- ^ Goldenberg, Suzanne (16 October 1999). "Musharraf strives to soften coup image". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ Weiner, Tim, and Steve Levine. "Pakistani General Forms New Panel to Govern the Nation" Archived 12 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times (18 October 1999).

- ^ a b c d Dugger, Celia W. "Pakistan's New Leader Is Struggling to Assemble His Cabinet" Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times (23 October 1999).

- ^ Kershner, Isabel, and Mark Landler. "Pakistan's Leaders Appoint Regional Governors" Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times (22 October 1999).

- ^ a b McCarthy, Rory (1 April 2000). "Sharif family alone against the military". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ "Pakistan profile – Timeline". BBC News. 28 November 2011. Archived from the original on 25 May 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.