Tanks of Cuba

Tanks have been utilized on the island of Cuba both within the military and within several conflicts,[1] with their usage and origin after World War II; the Cold War; and the modern era. This includes imported Soviet tanks in the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces today as well as American and British designs imported prior to the Cuban Revolution.

Overview

[edit]

Cuba originally had tanks from Great Britain and the United States and armored vehicles but didn't manufacture any. From these beginnings the modern Cuban Armoured forces grew and procured modern armoured fighting vehicles from Russia and Soviet Bloc that served during the Cold War, and various operations. One of the main Cuban operations using armor was in Angola in Africa.

History

[edit]Cuba in 1942 received military aid through the Lend-Lease program, and received eight Marmon-Herrington tanks from the U.S.[2] which became known in the Cuban army as the ‘3 Man Dutch’ [3] as they had been the model of tank sent to the Dutch East Indies campaign against the Japanese invasion in World War II.[4][5]

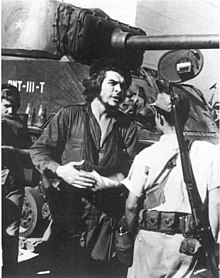

Cuba also got M3 Stuart tanks from the United States, as 24 of these light tanks arrived at Cuba under Lend Lease in 1942-1943 after the declaration of war to Germany. Later in 1957, 7 M4 Sherman tanks were received from the United States. They participated in the fights against the 26th of July Guerrilla Movement of Fidel Castro, fighting in Oriente (offensive of May 1958, Battle of Guise) and in the Battle of Santa Clara, in support of the Regiment "Leoncio Vidal" against Che Guevara. Some of these tanks were captured by the rebels, and the Shermans were displayed by the rebels riding the tanks when they triumphantly entered Havana, with Fidel on one of them.[6] Here, on January 1, 1959, was taken the famous photo of Che next to a Sherman which also saw action in the Battle of Santa Clara, as Batista sent 10 tanks, 12 armored cars along with an armored train and air support.[7][8][9]

Just before the revolution, Great Britain had sent 15 A34 Comet tanks[10] which were delivered to Cuba under Batista on 17 December 1958, and there are reports that some were used in the Battle of Santa Clara at the end of December 1959 by Batista's troops. Castro got these after he took over Cuba, and requested additional stocks of 77mm ammunition for the Comets as well as spare parts.[11]

When Fidel Castro seized power in January 1959, five of the eight Marmon-Herrington tanks were still operational. The new communist army, FAR (Revolutionary Armed Forces), retained them and shortly thereafter these five tanks were modified the original 37mm cannon replaced by a Bofors QF 20mm gun. The development of a strong armored force that could react quickly to any threat, whether internal or otherwise was a concern even at that stage.

In October 1960, the Cuban government needed tanks for which they could get ammunition not subject to US sanctions and turned to the Soviet Union for military aid from them and was supplied with T-34/85 tanks which allowed them to build up their armored forces. So by the time of Bay of Pigs in April 1961, there were in Cuba 125 T-34-85 and also 41 IS-2M tanks [12] that Cuba received. Some of the Sherman tanks also saw combat action against the anti-communist Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs (Playa Girón) along with the militia,[6] but the majority of the tanks and armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs) the Cuban Army used at the battle were Soviet, such as the T-34/85 and the SU-100.

The IS-2M tanks were in two regiments sent to the battle and were used as a reserve firing artillery support, while there were at least a force of 20 of the T-34-85 tanks fighting in the Bay of Pigs conflict and aided in the Cuban victory over the Brigade 2506 M41 Walker Bulldog tanks,[1] although five T-34-85 tanks were destroyed and others severely damaged.[13] Castro asked for more T-34-85 tanks after this to defend the island, and in September 1961 the request was up to 412 tanks, which began arriving just before the Missile Crisis.

Soon after their own revolution, many Cubans identified with the fledgling groups fighting for their independence. In Algeria, when France gave their independence, Castro decided to support them in their struggle with Morocco in the Sand War.[14] Castro was determined to prevent American domination and formed the Grupo Especial de Instrucción to use whose forces included twenty-two T-34-85 tanks, eighteen 120-mm mortars, a battery of 57-mm recoilless rifles, anti-aircraft artillery with eighteen guns, and eighteen 122mm field guns with the crews to operate them. They were described as an advisory contingent to train the Algerian army, but Castro allowed deployment in combat actions. Castro tried keep Cuba's intervention covert, but word of their presence soon leaked out.

In 1961 the Cuban Military began to provide support for the left wing MPLA movement in a civil war. The Angolan War of Independence was a struggle for control of Angola between guerilla movements and Portuguese colonial authority.[15] Castro had become familiar with the MPLA soon after it began, and after he came to power, Cuba had trained some of its guerrilla fighters, and Che Guevara had also made contact with its leaders.

So when Portugal left, Cuba sent advisors to help the MPLA and they quickly found themselves in the conflict when they lost men in the Battle of Quifangondo on 10 November 1975, the day before the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) declared Angola's independence from Portugal. Cuba supplied the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) rebels with weapons and soldiers along with tanks to fight as the Cuban military would fight alongside the MPLA in major battles.[16][17][18]

The arrival of the T-55 tanks in 1963 allowed Castro to send many of the older T-34-85 tanks to the conflict in Angola in 1975. All of the T-34s in Angola were armed with a ZiS-S-53 85mm main gun and two 7.62mm DT machine guns, with estimates as high as 200 T-34s used during the conflict.[citation needed] The T-34-85 tanks participated in Angola including the Battle of Cassinga where a Cuban mechanized battalion with T-34 tanks, and BTR-152 armoured personnel carriers were nearly destroyed, losing a half-dozen T-34s with another three heavily damaged. Cuba also received T-54s along with the T-55s, which formed the backbone of more than a thousand tanks that Russia would provide.[19]

Russian T-62s arrived in Cuba in 1976,[20] and by November 1987, shipments of T-54/55s were sent to Angola to replace the tanks lost. The assistance to the MPLA escalated till Cuban military aid helped the MPLA emerge victorious. Cuban T-62s along with T-55s and T-54Bs, were deployed to Angola during Havana's lengthy intervention in that country.

The more ubiquitous T-55 was favoured for combat duty, and during the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale only a single battalion of Cuban T-62s took part in the fighting. The Cuban tanks clashed with defending South African armoured units at Cuamato and again at Calueque without sustaining serious losses.

Organization of armored forces

[edit]

Fidel Castro ousted Batista on 31 December 1959, replacing his government with a revolutionary socialist state. Castro set up the Ministry of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Cuba (MINFAR) to oversee the Communist Party of Cuba and the government, as well as the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias – FAR).[21] In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, Castro's government began a program of nationalization and political consolidation that transformed Cuba's economy and society. He also reformed many aspects of Cuba's military and political organizations along communist lines, such as the 26 July Movement becoming the Communist Party in October 1965, and making a people's militia called the National Revolutionary Militia (MNR) as well as building the military which had the armored forces. It was the MMR which first engaged the counter-revolutionary force at the Bay of Pigs, with the tanks being sent once the regular army was sent by Castro.[22]

As he consolidated his government, Castro built up the number of tanks for the army. Cuban armored forces were organized at first to defend the revolutionary socialist state, and later enable intervention in foreign military conflicts. Military schools were founded for infantry, tank, artillery and communications training as well as reorganizing and expanding the regular Army at the expense of the common people in the MNR militia. The best of the militia members were transferred to the regular Army and armored forces, and in 1963 the militia was changed to a new military reserve organization, the Popular Defense Forces. Then after the defeat of counter-revolutionary forces in the mountains in 1965, the Popular Defense Forces were made into the Civil Defense headed by Raúl Castro. Then in 1980 the Territorial Troops Militia was created,[23] composed exclusively of civilian volunteers, which backed up the army while the Civil Defense focused on natural disasters relief.

The regular army with its armored forces has been involved in training others or foreign intervention with considerable Soviet military assistance. It reached its peak in 1975, with three armored divisions with over 1000 tanks, and 15 infantry divisions.[19] In offensive action in these interventions, tanks, reconnaissance armored vehicles, armored personnel carriers and artillery pieces of the first echelon unit normally attack using Soviet military doctrine, which if defending the tanks are dug in with the armored units and soldiers, while the heavy artillery forms up behind to support them.

Overview of tanks

[edit]Light and medium tanks

[edit]| Name | Country of origin | Quantity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marmon-Herrington Combat Tank | 8 | [24] |

| Name | Country of origin | Quantity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| M3 | 5 | [24] |

| Name | Country of origin | Quantity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| M4 | 15 | [24] |

| Name | Country of origin | Quantity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A34 | 5 | [24] |

| Name | Country of origin | Quantity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-34-85 | 150 | [24] | |

| PT-76 | 50 | [24] |

Heavy tanks

[edit]| Name | Country of origin | Quantity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| IS-2Ms | 41 | [24] |

Main battle tanks

[edit]| Name | Country of origin | Quantity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-54/55 | 800 | T-55Ms active[24] | |

| T-62 | 380 | T-62Ms active[24] |

See also

[edit]- History of the tank

- Tanks in World War II

- Tank classification

- List of military vehicles

- Cuban military ranks

- Cuban intervention in Angola

- Cuban Revolutionary Air and Air Defense Force

- Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces

- List of wars involving Cuba

- Military interventions of Cuba

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Cuban Tanks • Rubén Urribarres".

- ^ "Marmon-Herrington CTMS-ITB1". 9 June 2018.

- ^ "Cuban Tanks, I part • Rubén Urribarres". Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ Spoelstra, Hanno. "Marmon-Herrington tanks: The Dutch Connection". Marmon-Herrington Military Vehicles. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ Klemen, L. "The conquest of Java Island, March 1942". The Netherlands East Indies 1941–1942. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ a b "How Cuba Remembers Its Revolutionary Past and Present".

- ^ Rebelde, Radio. "Ernesto Che Gevara and the Big Battle for Santa Clara". www.radiorebelde.cu. Archived from the original on 4 November 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ "Cuba rebels, army battle for key city". Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ "Che Guevara in Santa Clara, Cuba". Havana Times. 16 September 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ "A34 Comet in Cuban Service - Tanks Encyclopedia". May 2018.

- ^ "A34 Comet in Cuban Service - Tanks Encyclopedia". www.tanks-encyclopedia.com. May 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ "IS-2 Heavy Tank". 30 June 2014.

- ^ "Enemy Tanks • Rubén Urribarres".

- ^ Article title [permanent dead link]

- ^ Williams, John Hoyt (1 August 1988). "Cuba: Havana's Military Machine". The Atlantic. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ "Cuba and the struggle for democracy in South Africa | South African History Online".

- ^ Brooke, James (February 1987). "Cuba's Strange Mission in Angola". The New York Times.

- ^ "Over Where? Cuban Fighters in Angola's Civil War". 20 October 2016.

- ^ a b "The Decline of the Cuban Armed Forces | Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses".

- ^ Rubén Urribarres. "Cuban tanks". Cuban Aviation. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Rebel army invades Cuba, battles for beachheads".

- ^ "Territorial Militia Troops".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Cuban Tanks". Cuban Aviation • Rubén Urribarres. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Jane's Intelligence Review, June 1993

- Defense Intelligence Agency, Handbook on the Cuban Armed Forces, DDB-2680-62-79, April 1979