Teochew Romanization

| Teochew Romanization Tiê-chiu Pe̍h-ūe-jī 潮州白話字 | |

|---|---|

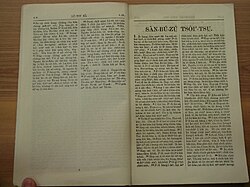

Bible in Teochew Romanised (1 Samuel), published by the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1915 | |

| Script type | (modified) |

| Creator | John Campbell Gibson William Duffus |

Period | c. 1875 — ? |

| Languages | Swatow dialect and Teochew dialect |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Latin script

|

| Transliteration of Chinese |

|---|

| Mandarin |

| Wu |

| Yue |

| Min |

| Gan |

| Hakka |

| Xiang |

| Polylectal |

| See also |

Teochew Romanization, also known as Swatow Church Romanization, or locally as Pe̍h-ūe-jī (Chinese: 白話字; lit. 'Vernacular orthography'), is an orthography similar to Pe̍h-ōe-jī used to write the Teochew language (including Swatow dialect). It was introduced by John Campbell Gibson and William Duffus, two British missionaries, to Swatow in 1875.

History

[edit]Romanization of Teochew can be traced back to the 1840s. The earliest attempt to write the language in the Latin script was undertaken by Baptist missionary William Dean in his 1841 publication First Lessons in the Tie-chiw Dialect published in Bangkok, Thailand[1]; however, his tonal system was said to be incomplete.[2]

The first complete orthographic system was devised by John Campbell Gibson and William Duffus, two Presbyterianism missionaries, in 1875. The orthography was generally based on the Pe̍h-ōe-jī system, another work of presbyterian origin devised for the Amoy dialect. The first translation of the Gospel of Luke in Swatow romanization was published in 1876.[2][3] It has been said[by whom?] that the vernacular orthographic system is more easier for illiterate persons to learn in their own mother tongue.

Besides Gibson and Duffus's original romanization system, several variations of the system were later devised, such as those by William Ashmore (1884)[4] and Lim Hiong Seng (1886).[5]

Other systems developed by Baptist missionaries such as Adele Marion Fielde (1883) and Josiah Goddard (1888) were generally used as a means of phonetic notation instead of a full orthographic system.[2][3]

Through the church's use of the romanization system, the number of users of the system grew and came to its high point in the 1910s. However, starting in the 1920s, the Chinese government promoted education in Mandarin and more people learned to read and write in Chinese characters. Thus, the promotion of romanized vernacular writing become less necessary.[2][3] By the 1950s, there were an estimated one thousand users of the system remaining in the Chaoshan area.[6]

Spelling schemes

[edit]Alphabet

[edit]The orthography uses 18 letters of the basic Latin alphabet.

| Capital letters | A | B | CH | CHH | E | G | H | I | J | K | KH | L | M | N | ᴺ | NG | O | P | PH | S | T | TH | TS | TSH | U | Ṳ | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowercase letters | a | b | ch | chh | e | g | h | i | j | k | kh | l | m | n | ⁿ | ng | o | p | ph | s | t | th | ts | tsh | u | ṳ | z |

Initial

[edit]The initial consonants in Teochew are listed below:[7]

The letters in the table represent the initial with its pronunciation in IPA, followed by the example of Chinese word and its translation in Teochew romanization.

| Lateral | Nasal | Stop | Affricate | Fricative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaspirated | Aspirated | Unaspirated | Aspirated | |||||

| Bilabial | Voiceless | p [p] 邊 (pian) |

ph [pʰ] 頗 (phó) |

|||||

| Voiced | m [m] 門 (mûn) |

b [b] 文 (bûn) |

||||||

| Alveolar | Voiceless | t [t] 地 (tī) |

th [tʰ] 他 (tha) |

ts [ts] 之 (tsṳ) |

tsh [tsʰ] 出 (tshut) |

s [s] 思 (sṳ) | ||

| Voiced | l [l] 柳 (liú) |

n [n] 挪 (nô) |

z [dz] 而 (zṳ̂) |

|||||

| Alveolo-palatal | Voiceless | ch [tɕ] 貞 (cheng) |

chh [tɕʰ] 刺 (chhì) |

s [ɕ] 時 (sî) | ||||

| Voiced | j [dʑ] 入 (ji̍p) |

|||||||

| Velar | Voiceless | k [k] 球 (kiû) |

kh [kʰ] 去 (khṳ̀) |

|||||

| Voiced | ng [ŋ] 俄 (ngô) |

g [ɡ] 語 (gṳ́) |

||||||

| Glottal | Voiceless | h [h] 喜 (hí) | ||||||

The affricate consonants ts/ch, tsh/chh, and z/j are three allophone pairs where those voiced and voiceless alveolar affricate will shift to voiced and voiceless alveolo-palatal affricate when they meet with close or close-mid front vowels (i, e).

Finals

[edit]The rhymes used in the orthography are listed below:[7][8]

The latin alphabet sets in the table represent the spelling of syllable final in the system with its pronunciation in IPA, followed by the example of Chinese word and its translation in Teochew romanization.

| Vowels | Coda-ending | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Types

|

Articulation | Simple | Nasal | Glottal Stop | Bilabial | Alveolar | Velar | |||||

| Backness | Height | Simple | Nasal | Nasal | Stop | Nasal | Stop | Nasal | Stop | |||

| Front | Open | a [a] 膠 (ka) |

aⁿ [ã] 柑 (kaⁿ) |

ah [aʔ] 甲 (kah) |

ahⁿ [ãʔ] 垃 (na̍hⁿ) |

am [am] 甘 (kam) |

ap [ap̚] 鴿 (kap) |

an [an] 干 (kan) |

at [at̚] 結 (kat) |

ang [aŋ] 江 (kang) |

ak [ak̚] 覺 (kak) | |

| Mid | e [e] 家 (ke) |

eⁿ [ẽ] 更 (keⁿ) |

eh [eʔ] 格 (keh) |

ehⁿ [ẽʔ] 脈 (me̍hⁿ) |

eng [eŋ] 經 (keng) |

ek [ek̚] 革 (kek) | ||||||

| Close | i [i] 枝 (ki) |

iⁿ [ĩ] 天 (thiⁿ) |

ih [iʔ] 砌 (kih) |

ihⁿ [ĩʔ] 碟 (tihⁿ) |

im [im] 金 (kim) |

ip [ip̚] 急 (kip) |

in [in] 新 (sin) |

it [it̚] 吉 (kit) |

||||

| Back | Mid | o [o] 高 (ko) |

oⁿ [õ] 望 (mōⁿ) |

oh [oʔ] 閣 (koh) |

ohⁿ [õʔ] 瘼 (mo̍hⁿ) |

ong [oŋ] 公 (kong) |

ok [ok̚] 國 (kok) | |||||

| Close | u [u] 龜 (ku) |

uh [uʔ] 嗝 (kuh) |

un [un] 君 (kun) |

ut [ut̚] 骨 (kut) |

||||||||

| ṳ [ɯ] 車 (kṳ) |

ṳh [ɯʔ] 嗻 (tsṳ̍h) |

ṳn [ɯn] 巾 (kṳn) |

ṳt [ɯt̚] 乞 (khṳt) |

|||||||||

| Front | Closing | ai [ai] 皆 (kai) |

aiⁿ [ãĩ] 愛 (àiⁿ) |

aih [aiʔ] 𫠡 (ga̍ih) |

aihⁿ [ãiʔ] 捱 (nga̍ihⁿ) |

|||||||

| Backward | au [au] 交 (kau) |

auⁿ [ãũ] 好 (hàuⁿ) |

auh [auʔ] 樂 (ga̍uh) |

auhⁿ [ãuʔ] 鬧 (nauhⁿ) |

||||||||

| Front | Opening | ia [ia] 佳 (kia) |

iaⁿ [ĩã] 京 (kiaⁿ) |

iah [iaʔ] 揭 (kiah) |

iam [iam] 兼 (kiam) |

iap [iap̚] 劫 (kiap) |

iang [iaŋ] 姜 (kiang) |

iak [iak̚] 龠 (iak) | ||||

| ie [ie] 蕉 (chie) |

ieⁿ [ĩẽ] 薑 (kieⁿ) |

ieh [ieʔ] 借 (chieh) |

ien [ien] 堅 (kien) |

iet [iet̚] 潔 (kiet) |

||||||||

| Backward | iong [ioŋ] 恭 (kiong) |

iok [iok̚] 鞠 (kiok) | ||||||||||

| Close | iu [iu] 鳩 (khiu) |

iuⁿ [ĩũ] 幼 (iùⁿ) |

||||||||||

| Forward | Closing | oi [oi] 雞 (koi) |

oiⁿ [õĩ] 間 (koiⁿ) |

oih [oiʔ] 夾 (koih) |

||||||||

| Back | ou [ou] 孤 (kou) |

ouⁿ [õũ] 虎 (hóuⁿ) |

||||||||||

| Forward | Opening | ua/oa[a] [ua] 柯 (kua) |

uaⁿ/oaⁿ [ũã] 官 (kuaⁿ) |

uah/oah [uaʔ] 割 (kuah) |

uam [uam] 凡 (huâm) |

uap [uap̚] 法 (huap) |

uan [uan] 關 (kuan) |

uat [uat̚] 決 (kuat) |

uang [uaŋ] 光 (kuang) |

uak [uak̚] 廓 (kuak) | ||

| ue [ue] 瓜 (kue) |

ueⁿ [ũẽ] 果 (kúeⁿ) |

ueh [ueʔ] 郭 (kueh) |

uehⁿ [uẽʔ] 襪 (gu̍ehⁿ) |

|||||||||

| Close | ui [ui] 規 (kui) |

uiⁿ [ũĩ] 跪 (kũiⁿ) |

||||||||||

| Backward | Close-up | iau [iau] 驕 (kiau) |

iauⁿ [ĩãũ] 掀 (hiauⁿ) |

iauh [iauʔ] 躍 (iauh) |

iauhⁿ [iãuʔ] 躍 (iauhⁿ) |

|||||||

| iou[b] [iou] 驕 (kiou) |

iouⁿ [ĩõũ] 掀 (hiouⁿ) |

iouh [iouʔ] 躍 (iouh) |

iouhⁿ[iõuʔ] 躍 (iouhⁿ) |

|||||||||

| Forward | uai [uai] 乖 (kuai) |

uaiⁿ [ũãĩ] 檨 (suāiⁿ) |

uaihⁿ [uãiʔ] 轉 (ua̍ihⁿ) |

|||||||||

| Syllabic consonant | ngh [ŋʔ] 夗 (n̍gh) |

m [m] 唔 (m̃) |

ng [ŋ] 黃 (n̂g) |

|||||||||

| hng [ŋ̊ŋ̍] 園 (hn̂g) |

||||||||||||

Nowadays, in most cities in Chaoshan, alveolar codas (-n/-t) have largely shifted to velar codas (-ng/-k); therefore, they are not found in the Peng'im system which was developed later in the 1960s. However, these codas are still present among native speakers particularly in few border townships like Fenghuang (鳳凰), Sanrao (三饒), and Nan'ao.

Tones

[edit]There are eight tones in Teochew and are indicated as below,

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese Tone names (modern) |

Dark-level 陰平 (Im-phêⁿ) |

Dark-rising 陰上 (Im-siãng) |

Dark-departing 陰去 (Im-khṳ̀) |

Dark-entering 陰入 (Im-ji̍p) |

Light-level 陽平 (Iâng-phêⁿ) |

Light-rising 陽上 (Iâng-siãng) |

Light-departing 陽去 (Iâng-khṳ̀) |

Light-entering 陽入 (Iâng-ji̍p) |

| Chinese Tone names (alternative)[9] |

Upper-even 上平 (Chiẽⁿ-phêⁿ) |

Upper-high 上上 (Chiẽⁿ-siãng) |

Upper-going 上去 (Chiẽⁿ-khṳ̀) |

Upper-entering 上入 (Chiẽⁿ-ji̍p) |

Lower-even 下平 (Ẽ-phêⁿ) |

Lower-high 下上 (Ẽ-siãng) |

Lower-going 下去 (Ẽ-khṳ̀) |

Lower-entering 下入 (Ẽ-ji̍p) |

| Chinese Tone names (traditional)[5][10] |

Upper-level 上平 (Chiẽⁿ-phêⁿ) |

Rising 上聲 (Siãng-siaⁿ) |

Upper-departing 上去 (Chiẽⁿ-khṳ̀) |

Upper-entering 上入 (Chiẽⁿ-ji̍p) |

Lower-level 下平 (Ẽ-phêⁿ) |

Lower-departing 下去 (Ẽ-khṳ̀) |

Departing 去聲 (Khṳ̀-siaⁿ) |

Lower-entering 下入 (Ẽ-ji̍p) |

| Pitches | ˧ (33) | ˥˨ (52) | ˨˩˧ (213) | ˨ (2) | ˥ (55) | ˧˥ (35) | ˩ (11) | ˦ (4) |

| Tone types | Mid level | High falling | Low dipping | Low stop | Top level | High rising | Bottom level | High stop |

| Diacritics | none | Acute accent | Grave accent | none | Circumflex | Tilde | Macron | Overstroke |

| Example | hun 分 | hún 粉 | hùn 訓 | hut 忽 | hûn 雲 | hũn 混 | hūn 份 | hu̍t 佛 |

| Sandhi | 1 | 6 | 2 or 5 | 8 | 7 or 3 | 3 or 7 | 7 or 3 | 4 |

Both the first and the fourth tones are unmarked but can be differenced by their coda-endings; those with the first tone end with an open vowel which could be either simple or nasalised, or end in a nasal consonant such as -m, -n, -ng, while those with the fourth tone end with a stop consonant such as -p, -t, -k, and -h.

Teochew features tone sandhi where for any compound that contains more than one word (a syllable), sandhi rules apply to all words except the last one in each phrase. For example, in the Swatow dialect, Tiê-chiu Pe̍h-ūe-jī would be pronounced as Tiē-chiu Peh-ùe-jī, where all words in the compound (linked by a hyphen) undergo tone sandhi except for the final word in each compound: chiu and jī. The tones markings of each word do not actually change to indicate tone sandhi and are written with their original tone markings.

References

[edit]- ^ Dean, William (1841). First Lessons in the Tie-chiw Dialect. Bangkok.

- ^ a b c d Snow, Don; Nuanling, Chen (2015-04-01). "Missionaries and written Chaoshanese". Global Chinese. 1 (1): 5–26. doi:10.1515/glochi-2015-1001. ISSN 2199-4382.

- ^ a b c Klöter, Henning; Saarela, Mårten Söderblom (6 October 2020). Language Diversity in the Sinophone World: Historical Trajectories, Language Planning, and Multilingual Practices. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-20148-2.

- ^ Ashmore, William (1884). Primary Lessons in Swatow Grammar (colloquial). Swatow: English Presbyterian Mission Press.

- ^ a b Lim, Hiong Seng (1886). "Tones, Hyphens". Handbook of the Swatow Vernacular. Singapore. p. 40.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "關於白話字-中國南方白話字發展". 台灣白話字文獻館 (in Traditional Chinese). 國立台灣師範大學. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- ^ a b Ma, Chongqi (2014). "A Comparative Research on Phonetic Systems of Four Swatow Dialect Works by Western Missionaries in the 1880s" (PDF). Research in Ancient Chinese Language (4): 10–22+95. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. PDF

- ^ Xu, Yuhang (2013). "The Phonological System of the Chaozhou Dialect in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). Journal of Chinese Studies (57): 223–244. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-06-21.

- ^ Fielde, Adele Marion (1883). A pronouncing and defining dictionary of the Swatow dialect, arranged according to syllables and tones. Shangai: American Presbyterian Mission Press.

- ^ Lechler, Rudolf; Williams, Samuel Wells; Duffus, William (1883). English-Chinese Vocabulary of the Vernacular Or Spoken Language of Swatow. Swatow: English Presbyterian Mission Press.