The Missal of Thomas James

| The Missal of Thomas James | |

|---|---|

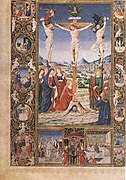

Frontispiece of the missal, fo 6 vo. | |

| Artist | Attavante degli Attavanti |

| Year | c. 1483-1484 |

| Medium | Oil on poplar panel |

| Dimensions | 39,2 cm × 28 cm (154 in × 11 in) |

| Location | Bibliothèque municipale de Lyon, Lyon |

| Accession | Ms 5123, Inv. 36.1 |

The Missal of Thomas James is an illuminated manuscript produced around 1483 for Thomas James, Bishop of Dol in Brittany. It represents the text of a missal for use in Rome and was commissioned by the Breton prelate, who was close to Pope Sixtus IV and Italian humanist circles while living in the papal city. The work was produced by the Italian painter Attavante degli Attavanti and the people of his studio in Florence. It contains two full-page miniatures, two-thirds-page miniatures, 165 historiated initials, and numerous margins decorated with medallions depicting saints or scenes from the life of Christ. These decorations are representative of Florentine Renaissance art, inspired by ancient objects and Flemish art. It served as a model for other manuscripts by the same painter, including The Missal of Matthias Corvin. The manuscript remained in Dol-de-Bretagne until the 19th century when it was sold and acquired by an archbishop of Lyon. It is currently kept in the Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon under the reference Ms.5123. However, it has been partially mutilated: the frontispiece has been cut out and five sheets have been removed. One of them, depicting the Crucifixion, is kept in the Museum of Modern Art André Malraux in Le Havre.

History

[edit]Context of creation

[edit]Attavante degli Attavanti, the painter who signed the manuscript (fo 6 vo), was a famous illuminator painter of the late 15th century. Many aristocrats and prelates from all over Europe sought to obtain a manuscript decorated by his hand, including Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary, Manuel I, King of Portugal, Georges d'Amboise, Archbishop of Rouen, and Lorenzo de' Medici.[1] The latter, through his diplomatic relations with Rome, helped to introduce Florentine artists to the papal city. Between 1477 and 1483, Sixtus IV invited the city's best artists to decorate the Sistine Chapel. Among them was Domenico Ghirlandaio, an artist who profoundly influenced the style of Attavante, with whom he probably collaborated. In particular, together with Domenico's brother Davide,[2] they collaborated on the decoration of the Bible of Federico da Montefeltro. In this context, one of the first works identified as coming from his studio was commissioned by a Breton monk living in Rome.

Patron and date

[edit]

The patron of this work can be identified by his coat of arms, which appears several times in the margins of the manuscript: "D'or, au chef d'azur chargé d'une rose d'or", which corresponds to that of Thomas James. He was a native of Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier with a doctorate in utroque jure, he pursued an ecclesiastical career in Brittany, holding several religious offices, including the title of archdeacon of Penthièvre. As a close friend of Pierre Landais, advisor to Francis II, Duke of Brittany, he began a career as a diplomat at the Holy See in Rome, which he joined in the 1470s, becoming a close friend of Pope Sixtus IV. He was appointed Bishop of Léon in 1478 (a bishopric to which he never returned), Governor of Castel Sant'Angelo at the end of 1478, and then Bishop of Dol in 1482. At that time he belonged to the entourage of Cardinal Guillaume d'Estouteville, Archbishop of Rouen, who probably introduced him to artistic circles. The humanist Giulio Pomponio Leto dedicated a Latin grammar to him in 1483, and he had an episcopal seal[3][4] engraved by Roman artisans.

The commission for the missal is known from two letters signed by the Florentine painter Attavante degli Attavanti, dated 1483 and 1484. They are addressed to Taddeo Gaddi (a descendant of the Florentine painter of the same name), who lived in the papal city and was responsible for supervising the production of the work on behalf of the client. The painter signed his letters "le miniaturiste de l'évêque de Dol" ("miniatore del vescovo di Dolo" in Italian). This commission, worth almost 200 ducats, probably dates back to his appointment as bishop of Dol. In July 1483, following the escape of a prisoner from the Castel Sant'Angelo, Thomas James was relieved of his governorship. James left Rome at the end of that year, probably because of the death of Cardinal d'Estouteville before the work was completed. It was his nephew François who enabled him to recover it in Florence in 1484, through the Rinieri family. Attavante signs the work on the frontispiece and gives the date of its creation: 1483.[5][6]

History of the manuscript

[edit]The manuscript is mentioned in the inventory of the bishop after he died in 1504. At that time it was valued at 1,200 ducats. On May 20, 1791, it was again listed in the inventory of the Cathedral: "Missel à l'usage de Rome en veslin garni de peintures" (Missal for the use of Rome in vellum decorated with paintings). It remained in the collections of the Dol Cathedral until the 19th century. In 1847, it was sold by the parish archpriest to a Parisian bookseller, after having unsuccessfully offered it to Godefroy Brossay-Saint-Marc, Archbishop of Rennes.It was quickly studied by the scholars Charles Cahier and Auguste de Bastard d'Estang. It was later sold to Cardinal Louis Jacques Maurice de Bonald, Archbishop of Lyon and a great art collector. After his death, it was donated, along with the rest of the archbishop's collection, to the Treasury of the Lyon Cathedral. It was rediscovered and studied for the first time by Léopold Delisle in 1882[7][8] and classified as a historical monument in 1902.[9] After the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State, the Primatial manuscripts were transferred to the Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon.[10]

Throughout its history, the manuscript has undergone several changes, including the removal of five sheets. Only one of these has been located: the Crucifixion, which is currently in the Museum of Modern Art André Malraux in Le Havre, where it was acquired in 1903 as a bequest from the Langevin-Berzan family. It is not known when the sheets were removed from the manuscript. It may have been cut out between the time it left Dol and its arrival in Lyon. It may also have been detached in the 18th century when it was rebound.[2]

Description

[edit]

Codicology

[edit]The work contains the traditional text of Roman missals in Latin:[11][12]

- A General Roman Calendar (fo 1-5 vo), the only particularity being the insertion of Saint Yves on October 27.

- The proper of Advent to the 25th Sunday after Pentecost (fo 6 vo-280), with the Mass in the Catholic Church inserted from folio 203.

- The proprer of saints (fo 280 vo-358).

- The commun of saints, dedication, votive Masses, and blessings (fo 358 vo-430).

The text is written in two columns of 26 lines each. It consists of 430 folio parchment sheets forming 8-sheet quires. The sheets, which measure 39.2 × 28 cm, were slightly cut when they were rebound in the 18th century. The manuscript is incomplete since five sheets are missing. Among the missing sheets are the one containing the months of November and December in the calendar (before the frontispiece, (fo 6 ro), as well as the sheet for the service on the first Sunday of Advent, after the frontispiece. Also missing from the center of the manuscript are the sheet before the beginning of the canon, the second one of the same canon, and the final sheet marking the beginning of the Easter service.

Decoration

[edit]The manuscript still contains two full-page miniatures, two third-page miniatures, 165 historiated initials, and numerous margins decorated with historiated vignettes.[10] One full-page miniature has been cut out and is now preserved in the Museum of Modern Art André Malraux in Le Havre, following a bequest in 1903 (inv.36.1).[6]

Frontispiece

[edit]The frontispiece (fo 6 vo, reproduced at the top of the page) contains a decoration covering the entire page and is used to frame the incipit of the missal text written in gold capital letters. The small central frame containing the text was cut out at an unknown date and remains empty today. The text was inscribed in a large carved altarpiece placed on an altar. The front of this altar is decorated with a bas-relief depicting the Triumph of Neptune and Amphitrite, inspired by the decoration on an Ancient Roman sarcophagi, now in the Villa Medici.[2][13]

It is surrounded by architectural and sculptural elements inspired by antiquity and the Florentine Renaissance. A two-story loggia facing a palace inspired by the Palazzo Medici Riccardi in Florence can be seen in the left background. The right background shows a building inspired by the Baptistery of Saint John in Florence facing another Roman basilica-inspired building. The artist's signature appears at the bottom: "ACTAVANTE DE ACTAVANTIBUS DE FLORENTIA / HOC OPUS ILLUMINAVIT + D MCCCCLXXXIII". The margin is decorated with numerous scrolls surrounding medallions that form small scenes. The medallions in the four corners depict sibyls dressed in the Florentine style. The medallion in the center left represents St. Antoninus of Florence, while the medallion in the center right represents St. Bonaventure. Six other medallions reproduce antique cameos from Lorenzo de' Medici collections. The two lower ones depict Bacchus discovering Ariadne in Naxos, and Le Char d'Ariane et de Bacchus trainé par des Psychés (now in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples). In the lower center margin, there is the coat of arms of the bishop, held by two cherubs.[14]

- Examples of ancient artworks similar to the models used for the frontispiece decorations

-

Cameo depicting Bacchus surprising Ariadne, coll. National Archaeological Museum of Florence.

Incipit of the Canon of the Mass

[edit]The other fully decorated page preserved in the manuscript is the beginning of the Canon of the Mass (fo 203 ro). The upper part of this page contains a miniature depicting the Last Judgement. The patron, Thomas James, is shown kneeling before St. Michael, bareheaded and tonsured. His face is barely represented, the painter had adopted an almost profil perdu to avoid drawing the features of a model he probably never met. The background of the scene shows landscapes inspired by Tuscany and a town with a church within its walls, inspired by the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower in Florence. In the lower-left corner, the T of "Te Igitur" is covered by a small painting depicting the Resurrection of Jesus. Twelve medallions depicting episodes before and after this scene of the gospel are placed in the decorated margin of the page: The Descent from the Cross, the Pietà, the Burial of Jesus, the Descent into Limbo, the Holy Women at the Tomb in the left margin from top to bottom. At the bottom of the page in two square vignettes: Noli me tangere and the Disciples of Emmaus. In the right margin from bottom to top: The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, the Ascension, the Assumption, and the Coronation of the Virgin. At the bottom of the page, the coat of arms of Thomas James appears again between two angels.[15]

Le Havre Folio

[edit]

The Havre Folio contains the Crucifixion, which was placed opposite Folio 203. Based on the canons of 15th-century Florentine painting, the full-page miniature is in the form of a small painting. It incorporates the influences of Early Netherlandish painting (once known as Flemish Primitives) with its attention to detail in landscapes lightly shrouded in mist and its rendering of materials. In the same position as on the previous page, but reversed, Thomas James is again depicted in a youthful blue robe, kneeling at the foot of St. John, bareheaded and tonsured. The city in the background shows several Roman monuments such as the dome of the Pantheon, the walls around St. Peter's Basilica, and the Castel Sant'Angelo. In the crowd is a red banner with the letters SPQR.[2][16]

The gilded frame surrounding the scene depicts episodes from the life of Jesus and his Passion. On the left are the Joyful Mysteries: from top to bottom, the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Epiphany, the Circumcision, Christ among the Doctors and, at the bottom left of the page, the Baptism. This last scene is a reproduction of the Baptism of Christ painted by Andrea del Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci. On the right, it's the Passion,[17] beginning with the Last Supper at the bottom right, then, from bottom to top, the Sorrowful Mysteries: La Prière dans le Jardin des oliviers (The Prayer in the Garden of Olives), the Arrest of Jesus, Jesus before Pilate, the Flagellation, to the Christ Carrying the Cross and the Crucifixion for the main scene.[16][18]

Incipit of the commun of saints and secondary decoration

[edit]The last and most decorated page is the incipit of the commun of saints (fo 358 vo). It depicts L'Assemblée céleste (The Heavenly Assembly) in the upper third of the page: the central group of figures is directly inspired by those present at the Last Judgment (fo 203 ro). Other decorations in the manuscript include eleven pages with decorated margins between fo 18 vo and fo 31 vo, each accompanied by a historiated initial. The margins are decorated with fine acanthus scrolls surrounding a medallion depicting biblical scenes. The remaining pages, up to fo 200, are simply illustrated with ornate initials and clusters of scrolls. In the second part (from fo 203 to the end), the pages contain the same scrolls as in the first part, accompanied by 150 initials depicting either a half figure, a group of figures or, more rarely, a complete scene.[19]

-

Le Paradis céleste, fo 358 vo.

-

Example of a decorated page from the first part, fo 29 vo.

-

Detail of a margin medallion: shepherds, fo 29 vo.

-

Example of a decorated page from the second part, fo 394 vo.

Attribution of the decoration

[edit]Not all of the illuminations in the manuscript are attributed to Attavante: the people of his studio was also involved in the decoration. The artist seems to have been involved in the frontispiece, the initial page of the canon and some of the initials in the first half of the volume: the Nativity (fo 16 vo), the Adoration of the Shepherds (fo 19 ro), the Virgin on a Throne (fo 20 ro), the Massacre of the Innocents (fo 24 ro), the Martyrdom of Thomas Becket (fo 25 vo), The Circumcision (fo 28 ro) and the Adoration of the Magi (fo 29 vo). The others are attributed to two close collaborators based on the less precise style of their contributions. One of them, considered the most skillful by art historians, is the sole author of the decorations for the incipit of the commun of saints (fo 358 ro) and produced the richest frames in the first part of the manuscript. The second half is entirely in the hands of the same two unidentified collaborators of the studio. The most skillful could be the author of the historiated initials in this section.[19] It has also been hypothesized that the master of Xenophon Hamilton (who had already worked with Attavante on the Bible of Federico da Montefeltro) participated in the decoration of the frontispiece[20] page.

-

Page with a frame attributed to the people of the studio and an initial to the artist, the Nativity, fo 16 vo

-

Example of an initial attributed to a collaborator, Évêque devant un autel, fo 394 vo.

Attavante's influence on other manuscripts

[edit]The decorations of the manuscript were repeated in other works later decorated by Attavante degli Attavanti and the people of his studio, for example, the Bréviaire de Matthias Corvin (Breviary of Matthias Corvin), now in the Vatican Library (Urb.lat.112), dated between 1487 and 1492, has the same type of frontispiece. But this is especially true of his missal now in the Royal Library of Belgium (Ms. 9008), dated between 1485 and 1487. The Missal of Thomas James is very close to the latter since Attavante used the same dimensions, the same models, the same sketches, and almost the same pagination for this second missal, written three years later. The miniature of the Crucifixion is almost identical, differing only in the background and some small details, such as the two angels above the Good Thief.[21] There is also a difference in the number of historiated initials in the second part of the manuscript: the Brussels manuscript contains only about 50, compared to 150 in the Lyon manuscript. This makes it possible to guess the content of the pages that have disappeared from the Lyon manuscript. For example, the page formerly opposite the frontispiece, at the beginning of the missal, contained medallions in the margins depicting scenes from the life of the Virgin and an initial depicting David. The Easter page contained a text depicting the Resurrection of Jesus.[22] The initial of the Nativity (fo 16 ro) is also found in another later work by Attavante: the Book of Hours in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (Ms. 154, fo 14 ro).[23]

-

Book of Hours with large initial of the Adoration du Christ (Adoration of Christ), Fitzwilliam Museum, Ms.154, fo 13 ro-fo 14 ro.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ferretti, Patrizia. "Attavanti, Attavante [Vante di Gabriello di Vante Attavanti]". Grove Art Online.

- ^ a b c d Labriola (2008, p. 111)

- ^ Bertaux & Birot (1906, pp. 129–130)

- ^ Osmond, Patricia. "Thomas James". Repertorium Pomponianum. (With additions by Diane Booton).

- ^ Bertaux & Birot (1906, pp. 130–131)

- ^ a b Bresc-Bautier, Crépin-Leblond & Taburet-Delahaye (2010, p. 360)

- ^ Delisle, Léopold (1882). "Le missel de Thomas James, évêque de Dol. Lettre à Mr le comte Auguste de Bastard". Bibliothèque de l'École des chartes (in French). 43: 311–315. doi:10.3406/bec.1882.447089.

- ^ Bertaux & Birot (1906, pp. 131–132)

- ^ "Manuscrit: missel de Thomas James, évêque de Dol". Ministère français de la Culture. (in French).

- ^ a b Missel d'Attavante

- ^ Horemans, Jean-Marie (1993). Le Missel de Mathias Corvin et la Renaissance en Hongrie (in French). Brussels. p. 61. ISBN 2870930801.

- ^ Bertaux & Birot (1906, p. 133)

- ^ Bober, Phyllis; Rubinstein, Ruth (1986). Renaissance Artists and Antique Sculpture: A Handbook of Sources. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781905375608.

- ^ Bertaux & Birot (1906, pp. 135, 136, 145, 146)

- ^ Bertaux & Birot (1906, pp. 136, 144)

- ^ a b Hatot & Jacob (2016)

- ^ Mauger, Michel (2002). Bretagne chatoyante: Une histoire du duché au Moyen Âge à travers l'enluminure Relié (in French). Apogée. ISBN 978-2843981265.

- ^ Bertaux & Birot (1906, pp. 142, 145)

- ^ a b Bertaux & Birot (1906, pp. 136–138)

- ^ Labriola & (2008, p. 112)

- ^ Horemans, Jean-Marie (1993). Le Missel de Mathias Corvin et la Renaissance en Hongrie (in French). Bibliothèque royale Albert Ier. pp. 78–79. ISBN 2870930801.

- ^ Bertaux & Birot (1906, pp. 139–140.)

- ^ Panayotova, Stella (2016). COLOUR: The Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts. Harvey Miller. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-909400-56-6.

Bibliography

[edit]- Delisle, Léopold (1882). "LE MISSEL DE THOMAS JAMES ÉVÊQUE DE DOL: LETTRE A M. LE COMTE AUGUSTE DE BASTARD". Bibliothèque de l'École des Chartes (in French). 43: 311–315. doi:10.3406/bec.1882.447089. JSTOR 43000308.

- Bertaux, Émile; Birot, G. (1906). "Le Missel de Thomas James, évêque de Dol". La Revue de l'art ancien et moderne (in French). 20: 129–146. ISSN 2021-0663.

- Leroquais, Victor (1924). Les sacramentaires et les missels manuscrits des bibliothèques publiques de France (in French). Vol. 3. Paris. pp. 223–225.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Joly, Henry (1931). Le missel d'Attavante pour Thomas James, évêque de Dol (in French). Lyon: les Amis de la Bibliothèque de Lyon.

- Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève; Crépin-Leblond, Thierry; Taburet-Delahaye, Elisabeth (2010). France 1500 : entre Moyen âge et Renaissance (Catalogue de l’exposition du Grand Palais à Paris) (in French). Paris: RMN. p. 360. ISBN 978-2-7118-5699-2.

- Hatot, Nicolas; Jacob, Marie (2016). Trésors enluminés de Normandie. Une (re)découverte (in French). PU DE RENNES. pp. 255–256. ISBN 9782753551770.

- Booton, Diane E. (2018). "Le mécénat et l'acculturation italienne de Thomas James, évêque de Dol-de-Bretagne, à la fin du xve siècle". Livres manuscrits et mécénat du Moyen Âge à la Renaissance (in French). Vol. 21. Pecia. Brepols: Pecia. Le livre et l’écrit. pp. 231–258. doi:10.1484/J.PECIA.5.118861. ISSN 2295-970X.

- Labriola, Ada (2008). Firenze e gli antichi Paesi Bassi 1430-1530 dialoghi tra artisti: da Jan van Eyck a Ghirlandaio, da Memling a Raffaello... (in Italian). Florence: Sillabe. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978888347730-0.

- "Ms 5123 // Missel". Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon (in French).

External links

[edit]- Fine arts resource: Manuscrit : missel de Thomas James, évêque de Dol (in French)

- Missel romain, dit missel d'Attavante. Commanditaire Thomas James, évêque de Dol (in French)

- Missel romain (in French)

- The Joyful Mysteries