The New Babylon

| The New Babylon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Grigori Kozintsev Leonid Trauberg |

| Written by | Grigori Kozintsev Leonid Trauberg P. Bliakin (idea) |

| Starring | Yelena Kuzmina Pyotr Sobolevsky Sergei Gerasimov Vsevolod Pudovkin Oleg Zhakov Yanina Zhejmo |

| Cinematography | Andrei Moskvin Yevgeny Mikhailov |

| Music by | Dmitri Shostakovich |

Production company | |

Release date |

|

Running time | German export edit: 125 minutes[1] (ca. 2,900 m) Gosfilmofond version: 93 min.[1] (ca. 2,170 m) European export edit: 84 min.[1] (ca. 1,900 m)[2] |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

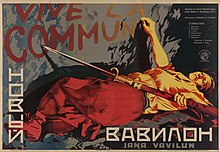

The New Babylon (Russian: Новый Вавилон, romanized: Novyy Vavilon alt. title: Russian: Штурм неба, romanized: Shturm neba) is a 1929 silent historical drama film written and directed by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg. The film deals with the 1871 Paris Commune and the events leading to it, and follows the encounter and tragic fate of two lovers separated by the barricades of the Commune.[3]

Composer Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his first film score for this movie. In the fifth reel of the score he quotes the revolutionary anthem, "La Marseillaise" (representing the Commune), juxtaposed contrapuntally with the famous "Can-can" from Offenbach's Orpheus in the Underworld.[4]

Footage from The New Babylon was included in Guy Debord's feature film The Society of the Spectacle (1973).

Kozintsev and Trauberg found some of their inspiration in Karl Marx's The Civil War in France[5] and The Class Struggle in France, 1848–50.[6][7]

Background

[edit]As one of the directors, Leonid Trauberg, later admitted, the film as it stands is a little difficult to follow. Its subtitle Assault on the Heavens: Episodes from the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, 1870–71 makes it fairly obvious that it is principally a political film, and not a love story. Some background knowledge of the Paris Commune is needed to understand what's going on around the two lovers. As Fiona Ford remarks, "Both New Babylon and Eisenstein's October are episodic in structure and require an intimate knowledge of their relevant historical periods (the Paris Commune of 1871 in the case of New Babylon) to better appreciate the directors' intentions and often simply to follow the diegesis."[8]

After the disastrous Franco-Prussian war of 1870, the victorious Prussian forces briefly surrounded Paris, cutting it off from the rest of the country, while a civil war was waged between the right-wing bourgeois-backed government backed by the tattered remains of the defeated French army (caps with a regimental number on a light stripe), and the left-wing workers and their National Guard (dark caps). One of the scenes in the film features the old bronze cannons of the National Guard, which had been paid for by public subscription.

The defeated nationalist government fled in disarray to the old royal Palace of Versailles some fifteen miles outside Paris. The workers took over large areas of central Paris and organised a Commune under the red flag, the world's first attempt at communist government.

Synopsis

[edit]The film is set in the spring of 1871 during the time of the Paris Commune, immediately after the end of the Franco-Prussian War. Louise is employed as a salesperson in a wholesale store in Paris named "The New Babylon". She is involved in the Commune, against which Jean, a young man from the countryside with no political affiliations, has to fight as a soldier in the army controlled by the French government. Louise and Jean are in love with each other although they are on opposing sides, but their love has no place in a time of political turmoil. At the end of the film, Jean is ordered to dig a grave for Louise, who has been sentenced to death by the court.

Cast

[edit]- Arnold Arnold – deputy

- Sergei Gerasimov – journalist Loutro

- David Gutman – owner of the shop "New Babylon"

- Oleg Zhakov – member of the Paris Commune

- Yanina Zhejmo – milliner Teresa

- Andrei Kostrichkin – bailiff

- Elena Kuzmina – saleswoman Louise

- Sofiya Magarill – actress

- Tamara Makarova – cancan dancer

- Vsevolod Pudovkin – bailiff

- Lyudmila Semyonova – cancan dancer

- Pyotr Sobolevsky – soldier Jean

- Eugene Chervyakov – soldier of the national guard

Production

[edit]The New Babylon was staged with members of the "Factory of the Eccentric Actor" (FEKS)[9] – an avant-garde artists' association founded by Kozintsev and Trauberg in 1922 that sought to create new paths in the performing arts. FEKS first began as a theater group, but in the following years, many of its members shaped the Russian-Soviet film history when working as actors, outfitters, and cinematographers. They wanted to get away from the naturalism and empathy aesthetics of bourgeois art, and saw Eccentrism (as laid out in Trauberg's Eccentric Manifesto)[10] as a new direction within the avant-garde that sought to find a place between Futurism, Surrealism and Dadaist Constructivism.

FEKS were influenced by street art and their cinematic preference was D. W. Griffith[11] and Chaplin,[12] not German expressionistic cinema of the early 1920s.[13] "Yesterday: salons, obeisances, barons. Today: yells of newsboys, scandals, policeman's truncheon, noise, scream, stomping, running," declared Kosintsev and Trauberg in their Manifesto of the Eccentric Actor.[10][14]

Like Kosintsev and Trauberg, twenty-two year old Dmitri Shostakovich was a member of the film group of "FEKS", dedicated to the abolition of the borders between theater, film, circus, music hall and opera. In his musical score he used various musical forms: dance and operetta melodies as well as French folk music and revolutionary songs: "Ça ira", "La Carmagnole" and "La Marseillaise"; it served as a leitmotif for the reactionary bourgeoisie and was used in various forms, such as can-can, waltz or gallop.

The score, which bears the Opus number 18, was lost shortly after the premiere, and was only discovered again shortly after Shostakovitch's death in 1975.[15]

The Russian premiere of The New Babylon took place on 18 March 1929 in Leningrad.

The score was of unprecedented complexity, and closely followed the fast cross-cuts of the film. Shostakovich himself performed the original solo piano score for two industry preview screenings. But the Sovkino censors ordered over 20% of the film to be removed, and attempts to re-edit the complex orchestral version of the score proved disastrous, with orchestras struggling to perform it. A copy of the piano score, originally intended for smaller cinemas, was rediscovered, and had its first live public performance on 25 March 2017 at the Barbican Centre in London.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c At 20 frames per second.

- ^ "Im Räderwerk der Filmzensur" (in German). arte. 25 October 2006. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ^ Jay Leyda (1960). Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film. George Allen & Unwin. pp. 258–260.

- ^ "CD Review, Building a Library: Elgar: Violin Concerto". BBC. BBC Radio 3. 14 January 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1871). The Civil War in France. Hosted at Marxists Internet Archive (English ed.). Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ Marx, Karl. The Class Struggle in France, 1848–50. Hosted at Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Mark (1990) New Babylon: Royal Northern College of Music, 30 June 1990 8.00 pm. Programme notes, p. 7

- ^ Ford, Fiona (2011). The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930) (PhD thesis). University of Nottingham. p. 183. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ "FEKS". Monoskop. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Eccentric Manifesto (1922/1992)". Monoskop. 27 November 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2017. With downloadable PDF.

- ^ so Taylor S. 148.

- ^ "Chaplin's bottom is dearer to us than the hand of Eleonora Duse." (cited by Lokke Heiss)

- ^ "arte.tv" (in German). Archived from the original on 11 September 2014.

- ^ "bibliotekar.ru" (in Russian).

- ^ Sheet music examples from Bernatchez, p. 263 ff.: Second musical examples, p. 263 1. Old French song from the 6th film part on "Das neue Babylon" (with text) – Tchaikovsky's Old French song from the album for youth, p 2. Excerpt from Gnessin's gallop, "A Jewish orchestra at the mayor's ball" and excerpt from the second part of the film about "The New Babylon".

- ^ "Shostakovich: New Babylon". London Symphony Orchestra. 25 March 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Houten, Theodore van; Taylor, Richard; University of Bristol. Library. Richard Taylor Russian Film Collection (1989). Leonid Trauberg and his films : always the unexpected. 's-Hertogenbosch [Netherlands]: Art & Research. ISBN 90-72058-03-8. OCLC 20309235.

- Houten, Theodore van (1991). 'Eisenstein was great eater' : in memory of Leonid Trauberg. 's-Hertogenbosch [Netherlands]: Art & Research. ISBN 90-72058-07-0. OCLC 24552753.

- Pytel, Marek (1999). New Babylon: Trauberg, Kozintsev, Shostakovich. London: Eccentric Press.

- Titus, Joan (1 April 2016). "New Babylon (1928–1929) and Scoring for the Silent Film". The Early Film Music of Dmitry Shostakovich. Oxford University Press. pp. 15–41. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199315147.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-931514-7.

- Stephen L. Hanson (2000). "Novyy Vavilon". In Tom Pendergast; Sara Pendergast (eds.). International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers. Vol. 1: Films (fourth ed.). London etc.: St. James Press. ISBN 978-1-55862-450-4.

- Vincent Canby (3 October 1983). "'New Babylon,' Silent Russian Classic". The New York Times.

External links

[edit]- The New Babylon at IMDb

- The New Babylon at AllMovie

- Jacques Poitrat, ed. (2006). "Новый Вавилон" (PDF) (in French). arte. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- 1929 films

- Soviet black-and-white films

- Soviet silent feature films

- Films directed by Grigori Kozintsev

- Films directed by Leonid Trauberg

- Films scored by Dmitri Shostakovich

- Films about the Paris Commune

- Soviet historical drama films

- 1920s historical drama films

- 1929 drama films

- Silent historical drama films

- 1920s Soviet films

- 1920s Russian-language films

- 1920s Soviet film stubs