Turkic mythology

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Turkic mythology |

|---|

|

Turkic mythology refers to myths and legends told by the Turkic people. It features Tengrist and Shamanist strata of belief along with many other social and cultural constructs related to the nomadic and warrior way of life of Turkic and Mongol peoples in ancient times.[1][2][3] Turkic mythology shares numerous ideas and practices with Mongol mythology.[1][2][3] Turkic mythology has also influenced other local Asiatic and Eurasian mythologies. For example, in Tatar mythology elements of Finnic and Indo-European mythologies co-exist. Beings from Tatar mythology include Äbädä, Alara, Şüräle, Şekä, Pitsen, Tulpar, and Zilant.

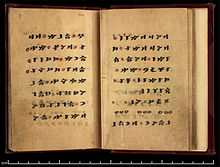

The ancient Turks apparently practised all the then-current major religions in Inner Asia, such as Tibetan Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, Judaism, and Manichaeism, before the majority's conversion to Islam through the mediation of Persian and Central Asian culture,[2][4] as well as through the preaching of Sufi Muslim wandering ascetics and mystics (fakirs and dervishes).[4][5] Often these other religions were assimilated and integrated through syncretism into their prevailing native mythological tradition, way of life, and worldview.[1][2][3][6] Irk Bitig, a 10th-century manuscript found in Dunhuang, is one of the most important sources for the recovery and study of Turkic mythology and religion. The book is written in Old Turkic alphabet like the Orkhon inscriptions.

Mythical creatures

[edit]- Archura, an evil forest demon.

- Qarakorshaq, a hiding animal-like creature that can be scared away by light and noise.[7]

- Tepegöz, a cyclops-like creature with only one eye on his forehead.[8]

- Tulpar, a winged horse.

- Yelbeghen, a creature described as a seven-headed giant or dragon.[9]

Mythical locations

[edit]Gods and spirits in Turkic mythology

[edit]

Turko-Mongol mythology is essentially polytheistic but became more monotheistic during the imperial period among the ruling class, and was centered around the worship of Tengri, the omnipresent Sky God.[11][12][13][1] Deities are personified creative and ruling powers. Even if they are anthropomorphised, the qualities of the deities are always in the foreground.[14][15]

İye are guardian spirits responsible for specific natural elements. They often lack personal traits since they are numerous.[14] Although most entities can be identified as deities or İye, there are other entities such as genien (Çor) and demons (Abasi).[14]

According to a common Turkic belief, the attitude of indefinite spirits is determined by their color: Good spirits appear white and evil spirits black.[16][17]

Tengri

[edit]Kök Tengri is the first of the primordial deities in the religion of the early Turkic people. After the Turks started to migrate and leave Central Asia and encounter monotheistic religions, Tengrism was modified from its pagan/polytheistic origins,[12] with only two of the original gods remaining: Tengri, representing goodness and Uçmag (a place like heaven), while Erlik represents evil and hell.

The words Tengri and Sky were synonyms and is maybe personification of the universe.[18]

Tengri's appearance is unknown. He rules the fates of all people and acts freely, but he is fair as he awards and punishes. The well-being of the people depends on his will. The oldest form of the name is recorded in Chinese annals from the 4th century BC, describing the beliefs of the Xiongnu. It takes the form 撑犁/Cheng-li, which is hypothesized to be a Chinese transcription of Tengri.[19]

Other deities

[edit]Umay (The Turkic root umāy originally meant 'placenta, afterbirth') is the goddess of fertility.[20]

Erlik (Old Turkic: 𐰀𐰼𐰠𐰃𐰚 is a deity associated with the dead and the underworld. According to the Khakas, Erlik resides in a palace in the lowest region of the netherworld.[21] Worship of Erlik is usually frowned upon,[22] After conversion to Islam, Erlik becomes associated with the Şeytan.[23]

Symbols

[edit]Horse

[edit]As a result of the Turks' nomadic lifestyle, the horse is also one of the main figures of Turkic mythology; Turks considered the horse an extension of the individual, particularly the male horse. This might have been the origin of the title "at-beyi" (horse-lord).[citation needed] As such, horses have been used in various Turkic rituals, including in funeral rites and burial practices. Turkology researcher Marat Kaldybayev has suggested that "the presence of a horse in funeral rites is one of the ethnocultural markers uniting Turkic cultures, starting from the ancient Turkic time and ending in the late Middle Ages."[24]

Dragons

[edit]The dragon (Ejderha; Evren, also Ebren), also depicted as a snake.[25] In Eastern Turkic myths, the dragon is a symbol of blessing and goodness.[26]

Tree

[edit]The World Tree or Tree of Life is a central symbol in Turkic mythology, and may have its origin in Central Asia.[27]

The tree of life connects the upper world, middle world and underworld. It is also imagined as the "white creator lord" (yryn-al-tojon).[28]

According to the Altai Turks, human beings are actually descended from trees. According to the Yakuts, Ak Ana sits at the base of the Tree of Life, whose branches reach to the heavens and are occupied by various supernatural creatures which have been born there. Yakut myth thus combines the cosmic tree with a mother goddess into a concept of nourishing and sustaining entity.[29]

Deer

[edit]Among animals, the deer was considered to be the mediator par excellence between the worlds of gods and men; thus at the funeral ceremony the soul of the deceased was accompanied in their journey to the underworld (Tamag) or abode of the ancestors (Uçmag) by the spirit of a deer offered as a funerary sacrifice (or present symbolically in funerary iconography accompanying the physical body) acting as psychopomp.[30]

In the Ottoman Empire, and more specifically in western Asia Minor and Thrace the deer cult seems to have been widespread, no doubt as a result of the meeting and mixing of Turkic with local traditions. A famous case is the 13th century holy man Geyiklü Baba (ie. 'father deer'), who lived with his deer in the mountain forests of Bursa and gave hind's milk to a colleague. Material in the Ottoman sources is not scarce but it is rather dispersed and very brief, denying us a clear picture of the rites involved.[31]

- In this instance the ancient funerary associations of the deer (literal or physical death) may be seen here to have been given a new (Islamic) slant by their equation with the metaphorical death of fanaa (the Sufi practice of dying-to-self) which leads to spiritual rebirth in the mystic rapture of baqaa.[32]

Epics

[edit]Grey Wolf legend

[edit]The wolf symbolizes honor and is also considered the mother of most Turkic peoples. Ashina is the name of one of the ten sons who were given birth to by a mythical wolf in Turkic mythology.[33][34][35]

The legend tells of a young boy who survived a raid in his village. A she-wolf finds the injured child and nurses him back to health. He subsequently impregnates the wolf which then gives birth to ten half-wolf, half-human boys. One of these, Ashina, becomes their leader and establishes the Ashina clan which ruled the Göktürks (T'u-chueh) and other Turkic nomadic empires.[36][37][38] The wolf, pregnant with the boy's offspring, escaped her enemies by crossing the Western Sea to a cave near to the Qocho mountains, one of the cities of the Tocharians. The first Turks subsequently migrated to the Altai regions, where they are known as experts in ironworking.[39]

Ergenekon legend

[edit]The Ergenekon legend tells about a great crisis of the ancient Turks. Following a military defeat, the Turks took refuge in the legendary Ergenekon valley where they were trapped for four centuries. They were finally released when a blacksmith created a passage by melting a mountain, allowing the gray wolf to lead them out.[40][41][42][43][44][45] A New Year's ceremony commemorates the legendary ancestral escape from Ergenekon.[46]

Korkut Ata stories

[edit]The Book of Dede Korkut from the 11th century covers twelve legendary stories of the Oghuz Turks, one of the major branches of the Turkic peoples. It originates from the state of Oghuz Yabghu period of the Turks, from when Tengriist elements in the Turkic culture were still predominant. It consists of a prologue and twelve different stories. The legendary story which begins in Central Asia is narrated by a dramatis personae, in most cases by Korkut Ata himself.[47] Korkut Ata heritage (stories, tales, music related to Korkut Ata) represented by Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkey was included in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity of UNESCO in November 2018 as an example of multi-ethnic culture.[48][49]

Epic of King Gesar in Turkic peoples

[edit]

They conclude that the stories of the Gesar cycle were well known in the territory of the Uyghur Khaganate.[50]

Orkhon Inscriptions and Creation narrative

[edit]The Old Turkic Orkhon inscriptions tells about Father-Heaven and Mother Earth giving raise to Mankind (child):

"When the blue Heaven above and the brown Earth beneath arose, between the twain Mindkind arose."[51]

See also

[edit]- Finnic mythology

- Hungarian mythology

- Mongol mythology

- Manchu mythology

- Tibetan mythology

- Scythian mythology

- Shamanism in Siberia

- Turkish folklore

- Susulu (mythology)

- Turkic creation myth

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Leeming, David A., ed. (2001). "Turko-Mongol Mythology". A Dictionary of Asian Mythology. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195120523.001.0001. ISBN 9780199891177.

- ^ a b c d M.L.D. (2018). "Türkic religion". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Vol. II. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1533–4. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-881625-6. LCCN 2017955557.

- ^ a b c Boyle, John A. (Autumn 1972). "Turkish and Mongol Shamanism in the Middle Ages". Folklore. 83 (3). Taylor & Francis on behalf of Folklore Enterprises, Ltd.: 177–193. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1972.9716468. ISSN 1469-8315. JSTOR 1259544. PMID 11614483. S2CID 27662332.

- ^ a b Findley, Carter V. (2005). "Islam and Empire from the Seljuks through the Mongols". The Turks in World History. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 56–66. ISBN 9780195177268. OCLC 54529318.

- ^ Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (January 1999). "Sufis and Shamans: Some Remarks on the Islamization of the Mongols in the Ilkhanate". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 42 (1). Leiden: Brill Publishers: 27–46. doi:10.1163/1568520991445605. ISSN 1568-5209. JSTOR 3632297.

- ^ JENS PETER LAUT Vielfalt türkischer Religionen p. 25 (German)

- ^ KALAFAT, Yaşar (1999), Doğu Anadoluda Eski Türk İnançlarının İzleri, Ankara: Atatürk Kültür Merkezi Yayını

- ^ "Türk Mitolojisinin, Kılıç İşlemeyen Şeytani Varlıklarından Biri: Tepegöz". Ekşi Şeyler (in Turkish). Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ "Cilbegän/Җилбегән". Tatar Encyclopedia. Kazan: Tatarstan Republic Academy of Sciences Institution of the Tatar Encyclopaedia. 2002.

- ^ Türk Söylence Sözlüğü (Turkish Mythological Dictionary), Deniz Karakurt, (OTRS: CC BY-SA 3.0)

- ^ "History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. 4". unesdoc.unesco.org. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ a b Klyashtornyj, Sergei G. (2008). Spinei, V. and C. (ed.). Old Turkic Runic Texts and History of the Eurasian Steppe. Bucureşti/Brăila: Editura Academiei Române; Editura Istros a Muzeului Brăilei.

- ^ Róna-Tas, A. (1987). W. Heissig; H.-J. Klimkeit (eds.). "Materialien zur alten Religion den Turken: Synkretismus in den Religionen zentralasiens" [Materials on the ancient religion of the Turks: syncretism in the religions of Central Asia]. Studies in Oriental Religions (in German). Wiesbaden. 13: 33–45

- ^ a b c Turkish Myths Glossary (Türk Söylence Sözlüğü), Deniz Karakurt(in Turkish)

- ^ Man 2004, pp. 402–404.

- ^ Zhanar, Abdibek, et al. "The Problems of the Mythological Personages in the Ancient Turkic Literature." Asian Social Science 11.7 (2015): 344.

- ^ Zarcone, Thierry, and Angela Hobart, eds. Shamanism and Islam: Sufism, healing rituals and spirits in the Muslim world. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017. p. 317

- ^ Bekebassova, A. N. "Archetypes of Kazakh and Japanese cultures." News of the national academy of sciences of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Series of social and human sciences 6.328 (2019): 87-93.

- ^ Jean-Paul Roux, Die alttürkische Mythologie, p. 255

- ^ Eason, Cassandra. Fabulous Creatures, Mythical Monsters, and Animal Power Symbols: A Handbook. Greenwood Press. 2008. p. 53. ISBN 978-02-75994-25-9.

- ^ Burnakov, V. A. "Erlik khan in the traditional worldview of the khakas." Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia 39.1 (2011): 107-114.

- ^ Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer Shamanism: Soviet Studies of Traditional Religion in Siberia and Central Asia: Soviet Studies of Traditional Religion in Siberia and Central Asia Routledge, 22. Juli 2016, ISBN 978-1-315-48724-3 S. 63

- ^ Moldagaliyev, Bauyrzhan Eskaliyevich, et al. "Synthesis of traditional and Islamic values in Kazakhstan." European Journal of Science and Theology 11.5 (2015): 217-229.

- ^ Marat, Kaldybayev (2023). "A horse in the funeral rites of the Turks as an ethnocultural marker". Cultural Dynamics. doi:10.1177/09213740231205015.

- ^ Ekici, Metin (2019). Dede Korkut kitabı: Türkistan/Türkmen sahra nüshası : soylamalar ve 13. boy : Salur Kazan'ın yedi başlı ejderhayı öldürmesi (in Turkish). Ötüken Neşriyat. ISBN 978-605-155-808-0.

- ^ Duman, Harun. "Türk mitolojisinde ejderha." Uluslararası Beşeri Bilimler ve Eğitim Dergisi 5.11 (2019): 484.

- ^ Knutsen, R. (2011). Tengu: The Shamanic and Esoteric Origins of the Japanese Martial Arts. Niederlande: Brill. p. 45

- ^ Dixon-Kennedy, M. (1998). Encyclopedia of Russian & Slavic Myth and Legend. Vereinigtes Königreich: ABC-CLIO. p. 282.

- ^ Dixon-Kennedy, M. (1998). Encyclopedia of Russian & Slavic Myth and Legend. Vereinigtes Königreich: ABC-CLIO.p. 282

- ^ "Deer totem in Turkic cultures". tengrifund.ru. 5 August 2014.

- ^ Laban Kaptein, Eindtijd en Antichrist, p. 32ff. Leiden 1997. ISBN 90-73782-90-2; Laban Kaptein (ed.), Ahmed Bican Yazıcıoğlu, Dürr-i Meknûn. Kritische Edition mit Kommentar, §§ 7.53; 14.136–14.140. Asch 2007. ISBN 978-90-902140-8-5

- ^ "Geyikli Baba". islamansiklopedisi.org.tr.

- ^ Book of Zhou, Vo. 50. (in Chinese)

- ^ History of Northern Dynasties, Vo. 99. (in Chinese)

- ^ Book of Sui, Vol. 84. (in Chinese)

- ^ Findley, Carter Vaughin. The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19-517726-6. Page 38.

- ^ Roxburgh, D. J. (ed.) Turks, A Journey of a Thousand Years. Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2005. Page 20.

- ^ Leeming, David Adams. A Dictionary of Asian Mythology. Oxford University Press. 2001. p. 178. ISBN 0-19-512052-3.

- ^ Christopher I. Beckwith, Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present, Princeton University Press, 2011, p.9

- ^ Oriental Institute of Cultural and Social Research, Vol. 1-2, 2001, p.66

- ^ Murat Ocak, The Turks: Early ages, 2002, pp.76

- ^ Dursun Yıldırım, "Ergenekon Destanı", Türkler, Vol. 3, Yeni Türkiye, Ankara, 2002, ISBN 975-6782-36-6, pp. 527–43.

- ^ İbrahim Aksu: The story of Turkish surnames: an onomastic study of Turkish family names, their origins, and related matters, Volume 1, 2006 , p.87

- ^ H. B. Paksoy, Essays on Central Asia, 1999, p.49

- ^ Andrew Finkle, Turkish State, Turkish Society, Routledge, 1990, p.80

- ^ Michael Gervers, Wayne Schlepp: Religion, customary law, and nomadic technology, Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies, 2000, p.60

- ^ Miyasoğlu, Mustafa (1999). Dede Korkut Kitabı.

- ^ "Intangible Heritage: Nine elements inscribed on Representative List". UNESCO. 28 November 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ "Heritage of Dede Qorqud/Korkyt Ata/Dede Korkut, epic culture, folk tales and music". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ Chadwick & Zhirmunsky 1969, pp. 263–4.

- ^ Büchner, V.F. and Doerfer, G., “Tañri̊”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 18 January 2023 doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_7392 First published online: 2012 First print edition: ISBN 9789004161214, 1960-2007

References

[edit]- Bonnefoy, Yves; Doniger, Wendy (1993). Asian Mythologies, University Of Chicago Press, pp. 315–339.

- Chadwick, Nora Kershaw; Zhirmunsky, Viktor (1969). Oral Epics of Central Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-14828-3.

- Hausman, Gerald; Hausman, Loretta (2003). The Mythology of Horses: Horse Legend and Lore Throughout the Ages. pp. 37–46.

- Heissig, Walter (2000). The Religions of Mongolia, Kegan Paul.

- Klyashtornyj, S. G. (2005). 'Political Background of the Old Turkic Religion' in: Oelschlägel, Nentwig, Taube (eds.), "Roter Altai, gib dein Echo!" Leipzig:FS Taube, ISBN 978-3-86583-062-3, pp. 260–265.

- Nassen-Bayer; Stuart, Kevin (October 1992). "Mongol creation stories: man, Mongol tribes, the natural world and Mongol deities". 2. 51. Asian Folklore Studies: 323–334. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Sproul, Barbara C. (1979). Primal Myths. HarperOne HarperCollinsPublishers. ISBN 978-0-06-067501-1.

- Türk Söylence Sözlüğü (Turkish Mythology Dictionary), Deniz Karakurt, (OTRS: CC BY-SA 3.0)

- 满都呼, 中国阿尔泰语系诸民族神话故事 [Folklores of Chinese Altaic races]. 民族出版社, 1997. ISBN 7-105-02698-7.

- 贺灵, 新疆宗教古籍资料辑注 [Materials of old texts of Xinjiang religions]. 新疆人民出版社, May 2006. ISBN 7-228-10346-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Kulsariyeva, Aktolkyn, Madina Sultanova, i Zhanerke Shaigozova. 2018. "The Shamanistic Universe of Central Asian Nomads: Wolves and She-Wolves". In: Przegląd Wschodnioeuropejski 9 (2): 231-40. https://doi.org/10.31648/pw.3192.