United Kingdom insolvency law

| Insolvency |

|---|

|

| Processes |

| Officials |

| Claimants |

| Restructuring |

| Avoidance regimes |

| Offences |

| Security |

| International |

| By country |

| Other |

United Kingdom insolvency law regulates companies in the United Kingdom which are unable to repay their debts. While UK bankruptcy law concerns the rules for natural persons, the term insolvency is generally used for companies formed under the Companies Act 2006. Insolvency means being unable to pay debts.[2] Since the Cork Report of 1982,[3] the modern policy of UK insolvency law has been to attempt to rescue a company that is in difficulty, to minimise losses and fairly distribute the burdens between the community, employees, creditors and other stakeholders that result from enterprise failure. If a company cannot be saved it is liquidated, meaning that the assets are sold off to repay creditors according to their priority. The main sources of law include the Insolvency Act 1986, the Insolvency Rules 1986 (SI 1986/1925, replaced in England and Wales from 6 April 2017 by the Insolvency Rules (England and Wales) 2016 (SI 2016/1024) – see below), the Company Directors Disqualification Act 1986, the Employment Rights Act 1996 Part XII, the EU Insolvency Regulation, and case law. Numerous other Acts, statutory instruments and cases relating to labour, banking, property and conflicts of laws also shape the subject.

UK law grants the greatest protection to banks or other parties that contract for a security interest. If a security is "fixed" over a particular asset, this gives priority in being paid over other creditors, including employees and most small businesses that have traded with the insolvent company. A "floating charge", which is not permitted in many countries and remains controversial in the UK, can sweep up all future assets, but the holder is subordinated in statute to a limited sum of employees' wage and pension claims, and around 20 per cent for other unsecured creditors. Security interests have to be publicly registered, on the theory that transparency will assist commercial creditors in understanding a company's financial position before they contract. However the law still allows "title retention clauses" and "Quistclose trusts" which function just like security but do not have to be registered. Secured creditors generally dominate insolvency procedures, because a floating charge holder can select the administrator of its choice. In law, administrators are meant to prioritise rescuing a company, and owe a duty to all creditors.[4] In practice, these duties are seldom found to be broken, and the most typical outcome is that an insolvent company's assets are sold as a going concern to a new buyer, which can often include the former management: but free from creditors' claims and potentially with many job losses. Other possible procedures include a "voluntary arrangement", if three-quarters of creditors can voluntarily agree to give the company a debt haircut, receivership in a limited number of enterprise types, and liquidation where a company's assets are finally sold off. Enforcement rates by insolvency practitioners remain low, but in theory an administrator or liquidator can apply for transactions at an undervalue to be cancelled, or unfair preferences to some creditors be revoked. Directors can be sued for breach of duty, or disqualified, including negligently trading a company when it could not have avoided insolvency.[5] Insolvency law's basic principles still remain significantly contested, and its rules show a compromise of conflicting views.

History

[edit]Duke: How shalt thou hope for mercy, rendering none?

Shylock: What judgment shall I dread, doing no wrong?

You have among you many a purchas’d slave,

Which, fike your asses and your dogs and mules,

You use in abject and in slavish parts,

Because you bought them; shall I say to you

"Let them be free, marry them to your heirs?

Why sweat they under burdens? let their beds

Be made as soft as yours, and let their palates

Be season'd with such viands?" You will answer

"The slaves are ours." So do I answer you:

The pound of flesh which I demand of him

Is dearly bought; 'tis mine, and I will have it.

If you deny me, fie upon your law!

There is no force in the decrees of Venice.

I stand for judgment: answer; shall I have it?

William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice (1598), Act IV, scene i

The modern history of corporate insolvency law in the UK began with the first companies legislation in 1844.[6] However, many principles of insolvency are rooted in bankruptcy laws that trace back to ancient times. Regulation of bankruptcy was a necessary part of every legal system, and is found in the Code of Hammurabi (18th century BC), the Twelve Tables of the Roman Republic (450 BC), the Talmud (200 AD), and the Corpus Juris Civilis (534 AD).[7] Ancient laws used a variety of methods for distributing losses among creditors, and satisfaction of debts usually came from a debtor's own body. A debtor might be imprisoned, enslaved or killed or all three. In England, Magna Carta (1215) clause 9 set out rules that people's land would not be seized if they had chattels or money to repay debts.[8] The Bankruptcy Act 1542 introduced the modern principle of pari passu (i.e. proportional) distribution of losses among creditors. However, the 1542 Act still reflected the ancient notion that people who could not pay their debts were criminals, and required debtors to be imprisoned.[9] The Fraudulent Conveyances Act 1571 ensured that any transactions by the debtor with "intent to delay, hinder or defraud creditors and others of their just and lawful actions" would be "clearly and utterly void".

The view of bankrupts as subject to the total will of creditors, well represented by Shylock demanding his "pound of flesh" in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, began to wane around the 17th century. In the Bankruptcy Act 1705,[10] the Lord Chancellor was given power to discharge bankrupts from having to repay all debts, once disclosure of all assets and various procedures had been fulfilled. Nevertheless, debtors' prison was a common end. Prisoners were frequently required to pay fees to the prison guards, making them further indebted; they could be bound in manacles and chains; and the sanitary conditions were foul. An early 18th century scandal broke after the friend of a Tory MP died in debtors' prison, and in February 1729 a Gaols Committee reported on the pestilent conditions. Nevertheless, the basic legislative scheme and moral sentiment remained the same. In 1769, William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England remarked it was not justifiable for any person other than a trader to "encumber himself with debts of any considerable value".[11] At the end of the century, Lord Kenyon in Fowler v Padget reasserted the old sentiment that "Bankruptcy is considered a crime and a bankrupt in the old laws is called an offender."[12]

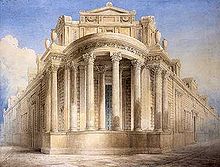

Since the South Sea Company and stock market disaster in 1720, limited liability corporations had been formally prohibited by law. This meant people who traded for a living ran severe risks to their life and health if their business turned bad, and they could not repay their debts. However, with the Industrial Revolution the view that companies were inefficient and dangerous,[13] was changing. Corporations became more and more common as ventures for building canals, water companies, and railways. The incorporators needed, however, to petition Parliament for a Local Act. In practice, the privilege of an investor to limit their liability upon insolvency was not accessible to the general business public. Moreover, the astonishing depravity of conditions in debtors' prison made insolvency law reform one of the most intensively debated issues on the 19th century legislative agenda. Nearly 100 bills were introduced to Parliament between 1831 and 1914.[14]

The long reform process began with the Insolvent Debtors (England) Act 1813. This established a specialist Court for the Relief of Insolvent Debtors. If their assets did not exceed £20, they might secure release from prison.

For people who traded for a living, the Bankruptcy Act 1825 (6 Geo. 4. c. 16) allowed the indebted to bring proceedings to have their debts discharged, without permission from the creditors.

The Gaols Act 1823 saw priests sent in, and put the debtors' prison jailors on the state's payroll, so they did not claim fees from inmates.

Under the Prisons Act 1835 five inspectors of prisons were employed.

| Insolvent Debtors Act 1842 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for the Relief of Insolvent Debtors. |

| Citation | 5 & 6 Vict. c. 116 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 12 August 1842 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

The Insolvent Debtors Act 1842 allowed non-traders to begin bankruptcy proceedings for relief from debts. Any person who was not a trader, or was a trader but owed less than £300, could obtain a protection order from the Court of Bankruptcy or a district court of bankruptcy halting all proceedings against him on condition that he vested all his property in an official assignee.

However, conditions remained an object of social disapprobation. The novelist Charles Dickens, whose own father had been imprisoned at Marshalsea while he was a child, pilloried the complexity and injustice through his books, especially David Copperfield (1850), Hard Times (1854) and Little Dorrit (1857). Around this very time reform began.

The difficulties for individuals to be discharged from debt in bankruptcy proceedings and the awfulness of debtors' prison made the introduction of modern companies legislation, and general availability of limited liability, all the more urgent. The first step was the Joint Stock Companies Act 1844, which allowed companies to be created through registration rather than a royal charter. It was accompanied by the Joint Stock Companies Winding-Up Act 1844, which envisaged a separate procedure to bring a company to an end and liquidate the assets. Companies had a legal personality separate from its incorporators, but only with the Limited Liability Act 1855 would a company's investors be generally protected from extra debts upon a company's insolvency. The 1855 Act limited investors' liability to the amount they had invested, so if someone bought shares in a company that ran up massive debts in insolvency, the shareholder could not be asked for more than he had already paid in. Thus, the risk of debtors' prison was reduced. Soon after, reforms were made for all indebted people. The Bankruptcy Act 1861 was passed allowing all people, not just traders, to file for bankruptcy. The Debtors Act 1869 finally abolished imprisonment for debt altogether. So the legislative scheme of this period came to roughly resemble the modern law. While the general principle remained pari passu among the insolvent company's creditors, the claims of liquidators expenses and wages of workers were given statutory priority over other unsecured creditors.[15] However, any creditor who had contracted for a security interest would be first in the priority queue. Completion of insolvency protection followed UK company law's leading case, Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd.[16] Here a Whitechapel bootmaker had incorporated his business, but because of economic struggles, he had been forced into insolvency. The Companies Act 1862 required a minimum of seven shareholders, so he had registered his wife and children as nominal shareholders, even though they played little or no part in the business. The liquidator of Mr Salomon's company sued him to personally pay the outstanding debts of his company, arguing that he should lose the protection of limited liability given that the other shareholders were not genuine investors. Salomon's creditors were particularly aggrieved because Salomon himself had taken a floating charge over all the company's present and future assets, and so his claims for debt against the company had ranked in priority to theirs. The House of Lords held that, even though the company was a one-man venture in substance, anybody who duly registered would have the protection of the Companies Acts in the event of insolvency. Salomon's case effectively completed the process 19th century reforms because any person, even the smallest business, could have protection from destitution following business insolvency.

Over the 20th century, reform efforts focused on three main issues. The first concerned setting a fair system of priority among claims of different creditors. This primarily centred upon the ability of powerful contractual creditors, particularly banks, to agree to take a security interest over a company's property, leaving unsecured creditors without any remaining assets to satisfy their claims. Immediately after Salomon's case and the controversy created over the use of floating charges, the Preferential Payments in Bankruptcy Amendment Act 1897 mandated that preferential creditors (employees, liquidator expenses and taxes at the time) also had priority over the holder of a floating charge (now Insolvency Act 1986 section 175). In the Enterprise Act 2002 a further major change was to create a ring-fenced fund for all unsecured creditors out of around 20 per cent of the assets subject to a floating charge.[17] At the same time, the priority for taxpayers' claims was abolished. Since then, debate for further reform has shifted to whether the floating charge should be abolished altogether and whether a ring-fenced fund should be taken from fixed security interests.[18] The second major area for reform was to facilitate the rescue of businesses that could still be viable. Following the Cork Report in 1982,[19] the Insolvency Act 1986 created the administration procedure, requiring (on paper) that the managers of insolvent businesses would attempt to rescue the company, and would act in all creditors' interests. After the Enterprise Act 2002 this almost wholly replaced the receivership rules by which secured creditors, with a floating charge over all assets, could run an insolvent company without regard to the claims of unsecured creditors. The third area of reform concerned accountability for people who worsened or benefited from insolvencies. As recommended by the Cork Report, the Company Directors' Disqualification Act 1986 meant directors who breached company law duties or committed fraud could be prevented from working as directors for up to 15 years. The Insolvency Act 1986 section 214 created liability for wrongful trading.[20] If directors failed to start the insolvency procedures when they ought to have known insolvency was inevitable, they would have to pay for the additional debts run up through prolonged trading. Furthermore, the provisions on fraudulent conveyances were extended, so that any transaction at an undervalue or other preference (without any bad intent) could be avoided, and unwound by an insolvent company.

The 2007–2008 financial crisis – which resulted from insufficient consumer financial protection in the United States, conflicts of interest in the credit rating agency industry, and defective transparency requirements in derivatives markets[21] – triggered a massive rise in corporate insolvencies. Contemporary debate, particularly in the banking sector, has shifted to prevention of insolvencies, by scrutinising excessive pay, conflicts of interest among financial services institutions, capital adequacy, and the causes of excessive risk-taking. The Banking Act 2009 created a special insolvency regime for banks, called the special resolution regime, envisaging that banks will be taken over by the government in extreme circumstances.

Corporate insolvency

[edit]

Corporate insolvencies happen because companies become excessively indebted. Under UK company law, a company is a separate legal person from the people who have invested money and labour into it, and it mediates a series of interest groups.[22] Invariably the shareholders, directors and employees' liability is limited to the amount of their investment, so against commercial creditors they can lose no more than the money they paid for shares, or their jobs. Insolvencies become intrinsically possible whenever a relationship of credit and debt is created, as frequently happens through contracts or other obligations. In the section of an economy where competitive markets operate, wherever excesses are possible, insolvencies are likely to happen. The meaning of insolvency is simply an inability to repay debts, although the law isolates two main further meanings. First, for a court to order a company be wound up (and its assets sold off) or for an administrator to be appointed (to try to turn the business around), or for avoiding various transactions, the cash flow test is usually applied: a company must be unable to pay its debts as they fall due. Second, for the purpose of suing directors to compensate creditors, or for directors to be disqualified, a company must be shown to have fewer overall assets than liabilities on its balance sheet. If debts cannot be paid back to everybody in full, creditors necessarily stand in competition with one another for a share of the remaining assets. For this reason, a statutory system of priorities fixes the order among different kinds of creditor for payment.

Companies and credit

[edit]

Companies are legal persons, created by registering a constitution and paying a fee, at Companies House. Like a natural person, a company can incur legal duties and can hold rights. During its life, a company must have a board of directors, which usually hires employees. These people represent the company, and act on its behalf. They can use and deal with property, make contracts, settle trusts, or maybe through some misfortune commission torts. A company regularly becomes indebted through all of these events. Three main kinds of debts in commerce are, first, those arising through a specific debt instrument issued on a market (e.g. a corporate bond or credit note), second, through loan credit advanced to a company on terms for repayment (e.g. a bank loan or mortgage) and, third, sale credit (e.g. when a company receives goods or services but has not yet paid for them.[23] However, the principle of separate legal personality means that in general, the company is the first "person" to have the liabilities. The agents of a company (directors and employees) are not usually liable for obligations, unless specifically assumed.[24] Most companies also have limited liability for investors. Under the Insolvency Act 1986 section 74(2)(d) this means shareholders cannot be generally sued for obligations a company creates. This principle generally holds wherever the debt arises because of a commercial contract. The House of Lords confirmed the "corporate veil" will not be "lifted" in Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd. Here, a bootmaker was not liable for his company's debts even though he was effectively the only person who ran the business and owned the shares.[25] In cases where a debt arises upon a tort against a non-commercial creditor, limited liability ceases to be an issue, because a duty of care can be owed regardless. This was held to be the case in Chandler v Cape plc, where a former employee of an insolvent subsidiary company successfully sued the (solvent) parent company for personal injury. When the company has no money left, and nobody else can be sued, the creditors may take over the company's management. Creditors usually appoint an insolvency practitioner to carry out an administration procedure (to rescue the company and pay creditors) or else enter liquidation (to sell off the assets and pay creditors). A moratorium takes effect to prevent any individual creditor enforcing a claim against the company. so only the insolvency practitioner, under the supervision of the court, can make distributions to creditors.

The causes of corporate failure, at least in the market segment of the economy, all begin of the creation of credit and debt.[26] Occasionally excessive debts are run up through outright embezzlement of the company's assets or fraud by the people who run the business.[27] Negligent mismanagement, which is found to breach the duty of care, is also sometimes found.[28] More frequently, companies go insolvent because of late payments. Another business on which the company relied for credit or supplies could also be in financial distress, and a string of failures could be part of a broader macroeconomic depression.[29] Periodically, insolvencies occur because technology changes which outdates lines of business. Most frequently, however, businesses are forced into insolvency simply because they are out-competed. In an economy organised around market competition, and where competition presupposes losers or contemplates excess, insolvencies necessarily happen.[30] The variety of causes for corporate failure means that the law requires different responses to the particular issues, and this is reflected in the legal meaning of insolvency.

Meaning of insolvency

[edit]

The meaning of insolvency matters for the type of legal rule. In general terms insolvency has, since the earliest legislation, depended upon inability to pay debts.[31] The concept is embodied in the Insolvency Act 1986 section 122(1)(f) which states that a court may grant a petition for a company to be wound-up if "the company is unable to pay its debts". This general phrase is, however, given particular definitions depending on the rules for which insolvency is relevant. First, the "cash flow" test for insolvency represented under section 123(1)(e) is that a company is insolvent if "the company is unable to pay its debts as they fall due". This is the main test used for most rules. It guides a court in granting a winding-up order or appoints an administrator.[32] The cash flow test also guides a court in declaring transactions by a company to be avoided on the ground they were at an undervalue, were an unlawful preference or created a floating charge for insufficient consideration.[33] The cash flow test is said to be based on a "commercial view" of insolvency, as opposed to a rigid legalistic view. In Re Cheyne Finance plc,[34] involving a structured investment vehicle, Briggs J held that a court could take into account debts that would become payable in the near future, and perhaps further ahead, and whether paying those debts was likely. Creditors may, however, find it difficult to prove in the abstract that a company is unable to pay its debts as they fall due. Because of this, section 122(1)(a) contains a specific test for insolvency. If a company owes an undisputed debt to a creditor of more than £750, the creditor sends a written demand, but after three weeks the sum is not forthcoming, this is evidence that a company is insolvent. In Cornhill Insurance plc v Improvement Services Ltd[35] a small business was owed money, the debt undisputed, by Cornhill Insurance. The solicitors had repeatedly requested payment, but none had come. They presented a winding up petition in the Chancery Court for the company. Cornhill Insurance's solicitors rushed to get an injunction, arguing that there was no evidence at all that their multi-million business had any financial difficulties. Harman J refused to continue the injunction noting that, if the insurance company had "chosen" not to pay, a creditor was also entitled to choose to present a winding up petition when a debt is undisputed on substantial grounds.[36]

English law draws a distinction between a "debt", which is relevant for the cash flow test of insolvency under section 123(1)(e), and a "liability", which becomes relevant for the second "balance sheet" test of insolvency under section 123(2). A debt is a sum due, and its quantity is a monetary sum, easily ascertained by drawing up an account. By contrast a liability will need to be quantified, as for instance, with a claim for a breach of contract and unliquidated damages. The balance sheet test asks whether "the value of the company's assets is less than the amount of its liabilities, taking into account its contingent and prospective liabilities."[37] This, whether total assets are less than liabilities, may also be taken into account for the purpose of the same rules as the cash flow test (a winding up order, administration, and voidable transactions). But it is also the only test used for the purpose of the wrongful trading rules, and director disqualification.[38] These rules potentially impose liability upon directors as a response to creditors being paid. This makes the balance sheet relevant, because if creditors are in fact all paid, the rationale for imposing liability on directors (assuming there is no fraud) drops away. Contingent and prospective liabilities refer to liability of a company that arise when an event takes place (e.g., defined as a contingency under a surety contract) or liabilities that may arise in future (e.g., probable claims by tort victims). The method for computing assets and liabilities depends on accountancy practice. These practices may legitimately vary. However, the law's general requirement is that accounting for assets and liabilities must represent a "true and fair view" of the company's finances.[39] The final approach to insolvency is found under the Employment Rights Act 1996 section 183(3), which gives employees a claim for unpaid wages from the National Insurance fund. Mainly for the purpose of certainty of an objectively observable event, for these claims to arise, a company must have entered winding up, a receiver or manager must be appointed, or a voluntary arrangement must have been approved. The main reason employees have access to the National Insurance fund is that they bear significant risk that their wages will not be paid, given their place in the statutory priority queue.

Priorities

[edit]"In a liquidation of a company and in an administration (where there is no question of trying to save the company or its business), the effect of insolvency legislation (currently the 1986 Act and the Insolvency Rules ...), as interpreted and extended by the courts, is that the order of priority for payment out of the company's assets is, in summary terms, as follows:

(1) Fixed charge creditors;

(2) Expenses of the insolvency proceedings;

(3) Preferential creditors;

(4) Floating charge creditors;

(5) Unsecured provable debts;

(6) Statutory interest;

(7) Non-provable liabilities; and

(8) Shareholders."

Re Nortel GmbH [2013] UKSC 52, [39], Lord Neuberger

Since the Bankruptcy Act 1542 a key principle of insolvency law has been that losses are shared among creditors proportionately. Creditors who fall into the same class will share proportionally in the losses (e.g. each creditor gets 50 pence for each £1 she is owed). However, this pari passu principle only operates among creditors within the strict categories of priority set by the law.[40] First, the law permits creditors making contracts with a company before insolvency to take a security interest over a company's property. If the security refers to some specific asset, the holder of this "fixed charge" may take the asset away free from anybody else's interest to satisfy the debt. If two charges are created over the same property, the charge holder with the first will have the first access. Second, the Insolvency Act 1986 section 176ZA gives special priority to all the fees and expenses of the insolvency practitioner, who carries out an administration or winding up. The practitioner's expenses will include the wages due on any employment contract that the practitioner chooses to adopt.[41] But controversially, the Court of Appeal in Krasner v McMath held this would not include the statutory requirement to pay compensation for a management's failure to consult upon collective redundancies.[42] Third, even if they are not retained, employees' wages up to £800 and sums due into employees' pensions, are to be paid under section 175. Fourth, a certain amount of money must be set aside as a "ring fenced fund" for all creditors without security under section 176A. This is set by statutory instrument as a maximum of £600,000, or 20 per cent of the remaining value, or 50 per cent of the value of anything under £10,000. All these preferential categories (for insolvency practitioners, employees, and a limited amount for unsecured creditors) come in priority to the holder of a floating charge.

Fifth, the holders of a floating charge holders must be paid. Like a fixed charge, a floating charge can be created by a contract with a company before insolvency. Like with a fixed charge, this is usually done in return for a loan from a bank. But unlike a fixed charge, a floating charge need not refer to a specific asset of the company. It can cover the entire business, including a fluctuating body of assets that is traded with day today, or assets that a company will receive in future. The preferential categories were created by statute to prevent secured creditors taking all assets away. This reflected the view that the power of freedom of contract should be limited to protect employees, small businesses or consumers who have unequal bargaining power.[43] After funds are taken away to pay all preferential groups and the holder of a floating charge, the remaining money due to unsecured creditors. In 2001 recovery rates were found to be 53% of one's debt for secured lenders, 35% for preferential creditors but only 7% for unsecured creditors on average.[44] Seventh comes any money due for interest on debts proven in the winding up process. In eighth place is money due to company members under a share redemption contract. Ninth are debts due to members who hold preferential rights. And tenth, ordinary shareholders, have the right to residual assets.

The priority system is reinforced by a line of case law, whose principle is to ensure that creditors cannot contract out of the statutory regime. This is sometimes referred to as the "anti-deprivation rule". The general principle, according to the Mellish LJ in Re Jeavons, ex parte Mackay[46] is that "a person cannot make it a part of his contract that, in the event of bankruptcy, he is then to get some additional advantage which prevents the property being distributed under the bankruptcy laws." So in that case, Jeavons made a contract to give Brown & Co an armour plates patent, and in return Jeavons would get royalties. Jeavons also got a loan from Brown & Co. They agreed half the royalties would pay off the loan, but if Jeavons went insolvent, Brown & Co would not have to pay any royalties. The Court of Appeal held half the royalties would still need to be paid, because this was a special right for Brown & Co that only arose upon insolvency. In a case where a creditor is owed money by an insolvent company, but also the creditor itself owes a sum to the company, Forster v Wilson[47] held that the creditor may set-off the debt, and only needs to pay the difference. The creditor does not have to pay all its debts to the company, and then wait with other unsecured creditors for an unlikely repayment. However, this depends on the sums for set-off actually being in the creditors' possession. In British Eagle International Air Lines Ltd v Compaigne Nationale Air France,[48] a group of airlines, through the International Air Transport Association had a netting system to deal with all the expenses they incurred to one another efficiently. All paid into a common fund, and then at the end of each month, the sums were settled at once. British Eagle went insolvent and was a debtor overall to the scheme, but Air France owed it money. Air France claimed it should not have to pay British Eagle, was bound to pay into the netting scheme, and have the sums cleared there. The House of Lords said this would have the effect of evading the insolvency regime. It did not matter that the dominant purpose of the IATA scheme was for good business reasons. It was nevertheless void. Belmont Park Investments Pty Ltd v BNY Corporate Trustee Services Ltd and Lehman Brothers Special Financing Inc observed that the general principle consists of two subrules — the anti-deprivation rule (formerly known as "fraud upon the bankruptcy law") and the pari passu rule, which are addressed to different mischiefs — and held that, in borderline cases, a commercially sensible transaction entered into in good faith should not be held to infringe the first rule. All these anti-avoidance rules are, however, subject to the very large exception that creditors remain able to jump up the priority queue, through the creation of a security interest.

Secured lending

[edit]

While UK insolvency law fixes a priority regime, and within each class of creditor distribution of assets is proportional or pari passu, creditors can "jump up" the priority ladder through contracts. A contract for a security interest, which is traditionally conceptualised as creating a proprietary right that is enforceable against third parties, will generally allow the secured creditor to take assets away, free from competing claims of other creditors if the company cannot service its debts. This is the first and foremost function of a security interest: to elevate the creditor's place in the insolvency queue. A second function of security is to allow the creditor to trace the value in an asset through different people, should the property be wrongfully disposed of. Third, security assists independent, out-of-court enforcement for debt repayment (subject to the statutory moratorium on insolvency), and so provides a lever against which the secured lender can push for control's over the company's management.[49] However, given the adverse distributional impact between creditors, the economic effect of secured lending is a negative externality against non-adjusting creditors.[50] With an ostensibly private contract between a secured lender and a company, assets that would be available to other creditors are diminished without their consent and without them being privy to the bargain. Nevertheless, security interests are commonly argued to facilitate the raising of capital and hence economic development, which is argued to indirectly benefits all creditors.[51] UK law has, so far, struck a compromise approach of enforcing all "fixed" or "specific" security interests, but only partially enforcing floating charges that cover a range of assets that a company trades with. The holders of a floating charge take subject to preferential creditors and a "ring fenced fund" for up to a maximum of £600,000 reserved for paying unsecured creditors.[52] The law requires that details of most kinds of security interests are filed on the register of charges kept by Companies House. However, this does not include transactions with the same effect of elevating creditors in the priority queue, such as a retention of title clause or a Quistclose trust.[53]

Debentures

[edit]In commercial practice the term "debenture" typically refers to the document that evidences a secured debt, although in law the definition may also cover unsecured debts (like any "IOU").[54] The legal definition is relevant for certain tax statutes, so for instance in British India Steam Navigation Co v IRC[55] Lindley J held that a simple "acknowledgement of indebtedness" was a debenture, which meant that a paper on which directors promised to pay the holder £100 in 1882 and 5% interest each half-year was enough, and as a result subject to pay duty under the Stamp Act 1870. The definition depends on the purpose of the statutory provision for which it is used. It matters because debenture holders have the right to company accounts and the director's report,[56] because debenture holders must be recorded on a company register which other debenture holders may inspect,[57] and when issued by a company, debentures are not subject to the rule against "clogs on the equity of redemption". This old equitable rule was a form of common law consumer protection, which held that if a person contracted for a mortgage, they must always have the right to pay off the debt and get full title to their property back. The mortgage agreement could not be turned into a sale to the lender,[58] and one could not contract for a perpetual period for interest repayments. However, because the rule limited on contractual freedom to protect borrowers with weaker bargaining power, it was thought to be inappropriate for companies. In Kreglinger v New Patagonia Meat and Cold Storage Co Ltd[59] the House of Lords held that an agreement by New Patagonia to sell sheepskins exclusively to Kreglinger in return for a £10,000 loan secured by a floating charge would persist for five years even after the principal sum was repaid. The contract to keep buying exclusively was construed to not be a clog on redeeming autonomy from the loan because the rule's purpose was to preclude unconscionable bargains. Subsequently, the clog on the equity of redemption rule as a whole was abolished by what is now section 739 of the Companies Act 2006. In Knightsbridge Estates Trust Ltd v Byrne[60] the House of Lords applied this so that when Knightsbridge took a secured loan of £310,000 from Mr Byrne and contracted to repay interest over 40 years, Knightsbridge could not then argue that the contract should be void. The deal created a debenture under the Act, and so this rule of equity was not applied.

Registration

[edit]

While all records of all a company's debentures need to be kept by the company, debentures secured by a "charge" must additionally be registered under the Companies Act 2006 section 860 with Companies House,[61] along with any charge on land, negotiable instruments, uncalled shares, book debts and floating charges, among other things. The purpose of registration is chiefly to publicise which creditors take priority, so that creditors can assess a company's risk profile when making lending decisions. The sanction for failure to register is that the charge becomes void, and unenforceable. This does not extinguish the debt itself, but any advantage from priority is lost and the lender will be an unsecured creditor. In National Provincial Bank v Charnley[62] there had been a dispute about which creditor should have priority after Mr Charnley's assets had been seized, with the Bank claiming its charge was first and properly registered. Giving judgment for the bank Atkin LJ held that a charge, which will confer priority, simply arises through a contract, "where in a transaction for value both parties evince an intention that property, existing or future, shall be made available as security for the payment of a debt, and that the creditor shall have a present right to have it made available, there is a charge". This means a charge simply arises by virtue of contractual freedom. Legal and equitable charges are two of four kinds of security created through consent recognised in English law.[63] A legal charge, more usually called a mortgage, is a transfer of legal title to property on condition that when a debt is repaid title will be reconveyed.[64] An equitable charge used to be distinct in that it would not be protected against bona fide purchasers without notice of the interest, but now registration has removed this distinction. In addition the law recognises a pledge, where a person hands over some property in return for a loan,[65] and a possessory lien, where a lender retains property already in their possession for some other reason until a debt is discharged,[66] but these do not require registration.

Fixed and floating charges

[edit]While both need to be registered, the distinction between a fixed and a floating charge matters greatly because floating charges are subordinated by the Insolvency Act 1986 to insolvency practitioners' expenses under section 176ZA,[67] preferential creditors (employees' wages up to £800 per person, pension contributions and the EU coal and steel levies) under section 175 and Schedule 6 and unsecured creditors' claims up to a maximum of £600,000 under section 176A. The floating charge was invented as a form of security in the late nineteenth century, as a concept which would apply to the whole of the assets of an undertaking. The leading company law case, Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd,[16] exemplified that a floating charge holder (even if it was the director and almost sole shareholder of the company) could enforce their priority ahead of all other persons. As Lord MacNaghten said, "Everybody knows that when there is a winding-up debenture-holders generally step in and sweep off everything; and a great scandal it is." Parliament responded with the Preferential Payments in Bankruptcy Amendment Act 1897, which created a new category of preferential creditors – at the time, employees and the tax authorities – who would be able to collect their debts after fixed charge holders, but before floating charge holders. In interpreting the scope of a floating charge the leading case was Re Yorkshire Woolcombers Association Ltd[68] where a receiver contended an instrument was void because it had not been registered. Romer LJ agreed, and held that the hallmarks of a floating charge were that (1) assets were charged present and future and (2) change in the ordinary course of business, and most importantly (3) until a step is taken by the charge holder "the company may carry on its business in the ordinary way".[69] A floating charge is not, technically speaking, a true security until a date of its "crystallisation", when it metaphorically descends and "fixes" onto the assets in a business' possession at that time.

Businesses, and the banks who had previously enjoyed uncompromised priority for their security, increasingly looked for ways to circumvent the effect of the insolvency legislation's scheme of priorities. A floating charge, for its value to be ascertained, must have "crystallised" into a fixed charge on some particular date, usually set by agreement.[70] Before the date of crystallisation (given the charge merely "floats" over no particular property) there is the possibility that a company could both charge out property to creditors with priority,[71] or that other creditors could set-off claims against property subject to the (uncrystallised) floating charge.[72] Furthermore, other security interests (such as a contractual lien) will take priority to a crystallised floating charge if it arises before in time.[73] But after crystallisation, assets received by the company can be caught by the charge.[74] One way for companies to gain priority with floating charges originally was to stipulate in the charge agreement that the charge would convert from "floating" to "fixed" automatically on some event before the date of insolvency. According to the default rules at common law, floating charges impliedly crystallise when a receiver is appointed, if a business ceases or is sold, if a company is would up, or if under the terms of the debenture provision is made for crystallisation on reasonable notice from the charge holder.[75] However an automatic crystallisation clause would mean that at the time of insolvency – when preferential creditors' claims are determined – there would be no floating charge above which preferential creditors could be elevated. The courts held that it was legitimate for security agreements to have this effect. In Re Brightlife Ltd[76] Brightlife Ltd had contracted with its bank, Norandex, to allow a floating charge to be converted to a fixed charge on notice, and this was done one week before a voluntary winding up resolution. Against the argument that public policy should restrict the events allowing for crystallisation, Hoffmann J held that in his view it was not "open to the courts to restrict the contractual freedom of parties to a floating charge on such grounds." Parliament, however, intervened to state in the Insolvency Act 1986 section 251 that if a charge was created as a floating charge, it would deem to remain a floating charge at the point of insolvency, regardless of whether it had crystallised.

‘A company has not the restraint which the fear of bankruptcy imposes on an individual trader... [For] directors of a company... little or no personal discredit falls upon them if their company fails to pay a dividend to its trade creditors. It is, therefore, all the more important that the amount and manner of borrowing by a corporation should be upon a satisfactory basis... We do not consider that a company should have any greater facility for borrowing than an individual, and we think that while a company should have unrestricted power to mortgage or charge its fixed assets and should be allowed to contract that other fixed assets substituted for those charged should become subject to the charge, and the company should also be capable of charging existing chattels and book debts or other things in action, it ought to be rendered incapable of charging after acquired chattels, or future book debts, or other property not in existence at the time of the creation of the charge.’

Minority of the Loreburn Committee, Report of the Company Law Amendment Committee (1906) Cd 3052, 28

Especially as automatic crystallisation ceased to make floating charges an effective form of priority, the next step by businesses was to contract for fixed charges over every available specific asset, and then take a floating charge over the remainder. It attempted to do this as well over book debts that a company would collect and trade with. In two early cases the courts approved this practice. In Siebe Gorman & Co Ltd v Barclays Bank Ltd[77] it was said to be done with a stipulation that the charge was "fixed" and the requirement that proceeds be paid into an account held with the lending bank. In Re New Bullas Trading Ltd[78] the Court of Appeal said that a charge could purport to be fixed over uncollected debts, but floating over the proceeds that were collected from the bank's designated account. However, the courts overturned these decisions in two leading cases. In Re Brumark Investments Ltd[79] the Privy Council advised that a charge in favour of Westpac bank that purported to separate uncollected debts (where a charge was said to be fixed) and the proceeds (where the charge was said to be floating) could not be deemed separable: the distinction made no commercial sense because the only value in uncollected debts are the proceeds, and so the charge would have to be the same over both.[80] In Re Spectrum Plus Ltd,[81] the House of Lords finally decided that because the hallmark of a floating charge is that a company is free to deal with the charged assets in the ordinary course of business, any charge purported to be "fixed" over book debts kept in any account except one which a bank restricts the use of, must be in substance a floating charge. Lord Scott emphasised that this definition "reflects the mischief that the statutory intervention... was intended to meet and should ensure that preferential creditors continue to enjoy the priority that section 175 of the 1986 Act and its statutory predecessors intended them to have."[82] The decision in Re Spectrum Plus Ltd created a new debate. On the one hand, John Armour argued in response that all categories of preferential would be better off abolished, because in his view businesses would merely be able to contract around the law (even after Re Spectrum Plus Ltd) by arranging loan agreements that have the same effect as security but not in a form caught by the law (giving the examples of invoice discounting or factoring).[83] On the other hand, Roy Goode and Riz Mokal have called for the floating charge simply to be abandoned altogether, in the same way as was recommended by the Minority of the Loreburn Report in 1906.[84]

Equivalents to security

[edit]Aside from a contract that creates a security interest to back repayment of a debt, creditors to a company, and particularly trade creditors may deploy two main equivalents security. The effect is to produce proprietary rights which place them ahead of the general body of creditors. First, a trade creditor who sells goods to a company (which may go into insolvency) can contract for a retention of title clause. This means that even though the seller of goods may have passed possession to a buyer, until the price of sale is paid, the seller has never passed property. The company and creditor agree that title to the property is retained by the seller until the date of payment. In the leading case, Aluminium Industrie Vaassen BV v Romalpa Aluminium Ltd[85] a Dutch company making aluminium foil stipulated in its contract with Romalpa Aluminium Ltd that when it supplied the foil, ownership would only passed once the price had been paid, and that any products made by Romalpa would be held by them as bailees. When Romalpa went insolvent, another creditor claimed that its floating charge covered the foil and products. The Court of Appeal held, however, that property in the foil had never become part of Romalpa's estate, and so could not be covered by the charge. Furthermore, the clause was not void for want to registration because only assets belonging to the company and then charged needed to be registered. In later cases, the courts have held that if property is mixed during a manufacturing process so that it is no longer identifiable,[86] or if it is sold onto a buyer,[87] then the retention of title clause ceases to have effect. If the property is something that can be mixed (such as oil) and the clause prohibits this, then the seller may retain a percentage share of the mixture as a tenant in common. But if the clause purports to retain title over no more than a part of the property, Re Bond Worth Ltd held that the clause must take effect in equity, and so requires registration.[88] The present requirements in the Companies Act 2006 section 860 continue not to explicitly cover retention of title clauses, in contrast to the registration requirements in the US Uniform Commercial Code article 9. This requires that anything with the same effect as a security interest requires registration, and so covers retention of title provision.

A second main equivalent to a security interest is a "Quistclose trust" named after the case Barclays Bank Ltd v Quistclose Investments Ltd.[89] Here a company named Rolls Razor Ltd had promised to pay a dividend to its shareholders, but had financial difficulty. Already in debt to its bank, Barclays, for £484,000 it agreed to take a loan from Quistclose Investments Ltd for £209,719. This money was deposited in a separate Barclays account, for the purpose of being paid out to shareholders. Unfortunately, Rolls Razor Ltd entered insolvency before the payment was made. Barclays claimed it had a right to set off the Quistclose money against the debts that were due to it, while Quistclose contended the money belonged entirely to it, and could not be used for the satisfaction of other creditors. The House of Lords unanimously held that a trust had been created in favour of Quistclose, and if the purpose of the payment (i.e. to pay the shareholders) failed, then the money would revert to Quistclose's ownership. While Quistclose trust cases are rare, and their theoretical basis has remained controversial (particularly because the trust is for a purpose and so sits uncomfortably with the rule against perpetuities), trusts have also been acknowledged to exist when a company keeps payments by consumers in a separate fund. In Re Kayford Ltd a mail order business, fearing bankruptcy and not wanting pre-payments by its customers to be taken by other creditors, acted on its solicitors' advice and placed their money in a separate bank account. Megarry J held this effectively ensured other creditors would not have access to this cash. Since the Insolvency Act 1986 reforms, it is probable that section 239, which prohibits transactions that desire to give a preference to one creditor over others, would be argued to avoid such an arrangement (if ever a company does in fact seek to prefer its customers in this way). The position, then, would be that while banks and trade creditors may easily protect themselves, consumers, employees and others in a weaker bargaining position have few legal resources to do the same.

Procedures

[edit]As a company nears insolvency, UK law provides four main procedures by which the company could potentially be rescued or wound down and its assets distributed. First, a company voluntary arrangement,[90] allows the directors of a company to reach an agreement with creditors to potentially accept less repayment in the hope of avoiding a more costly administration or liquidation procedure and less in returns overall. However, only for small private companies is a statutory moratorium on debt collection by secured creditors available. Second, and since the Enterprise Act 2002 the preferred insolvency procedure, a company which is insolvent can go under administration. Here a qualified insolvency practitioner will replace the board of directors and is charged with a public duty of rescuing the company in the interests of all creditors, rescuing the business through a sale, getting a better result for creditors than immediate liquidation, or if nothing can be done effecting an orderly winding up and distribution of assets. Third, administrative receivership is a procedure available for a fixed list of eight kinds of operation (such as public-private partnerships, utility projects and protected railway companies[91]) where the insolvency practitioner is appointed by the holder of a floating charge that covers a company's whole assets. This stems from common law receivership where the insolvency practitioner's primary duty was owed to the creditor that appointed him. After the Insolvency Act 1986 it was increasingly viewed to be unacceptable that one creditor could manage a company when the interests of her creditor might conflict with those holding unsecured or other debts. Fourth, when none of these procedures is used, the business is wound up and a company's assets are to be broken up and sold off, a liquidator is appointed. All procedures must be overseen by a qualified insolvency practitioner.[92] While liquidation remains the most frequent end for an insolvent company, UK law since the Cork Report has aimed to cultivate a "rescue culture" to save companies that could be viable.

Company voluntary arrangement

[edit]

Because the essential problem of insolvent companies is excessive indebtedness, the Insolvency Act 1986 sections 1 to 7 contain a procedure for companies to ask creditors to reduce the debt they are owed, in the hope that the company may survive. For instance, directors might propose that each creditor accepts 80 per cent of the money owed to each, and to spread repayments out over five years, in return for a commitment to restructure the business' affairs under a new marketing strategy. Under chapter 11 of the US Bankruptcy Code this kind of debt restructuring is usual, and the so-called "cram down" procedure allows a court to approve a plan over the wishes of creditors if they will receive a value equivalent to what they are owed.[94] However, under UK law, the procedure remains predominantly voluntary, except for small companies. A company's directors may instigate a voluntary arrangement with creditors, or if already appointed, an administrator or liquidator can also propose it.[95] Importantly, secured and preferential creditors' entitlements cannot be reduced without their consent.[96] The procedure takes place under the supervision of an insolvency practitioner, to whom the directors will submit a report on the company's finances and a proposal for reducing the debt.

When initially introduced, the CVA procedure was not frequently used because a single creditor could veto the plan, and seek to collect their debts. This changed slightly with the Enterprise Act 2002. Under a new section 1A of the Insolvency Act 1986, small companies may apply for a moratorium on debt collection if it has any two of (1) a turnover under £6.5m (2) under £3.26m on its balance sheet, or (3) fewer than 50 employees.[97] After an arrangement is proposed creditors will have the opportunity to vote on the proposal, and if 75 per cent approve the plan it will bind all creditors.[98] For larger companies, voluntary arrangements remain considerably under-used, particularly given the ability of administrators to be appointed out of court. Still, compared to the individual voluntary arrangement available for people in bankruptcy, company voluntary arrangements are rare.

Administration

[edit]After the Cork Report in 1982 a major new objective for UK insolvency law became creating a "rescue culture" for business, as well as ensuring transparency, accountability and collectivity.[99] The hallmark of the rescue culture is the administration procedure in the Insolvency Act 1986, Schedule B1 as updated by the Enterprise Act 2002. Under Schedule B1, paragraph 3 sets the primary objective of the administrator as "rescuing the company as a going concern", or if not usually selling the business, and if this is not possible realising the property to distribute to creditors. Once an administrator is appointed, she will replace the directors.[100] Under paragraph 40 all creditors are precluded by a statutory moratorium from bringing enforcement procedures to recover their debts. This even includes a bar on secured creditors taking and or selling assets subject to security, unless they get the court's permission.[101] The moratorium is fundamental to keeping the business' assets intact and giving the company a "breathing space" for the purpose of a restructure. It also extends to a moratorium on the enforcement of criminal proceedings. So in Environmental Agency v Clark[102] the Court of Appeal held that the Environment Agency needed court approval to bring a prosecution against a polluting company, though in the circumstances leave was granted. Guidance for when leave should be given by the court was elaborated in Re Atlantic Computer Systems plc (No 1).[103] In this case, the company in administration had sublet computers that were owned by a set of banks who wanted to repossess them. Nicholls LJ held leave to collect assets should be given if it would not impede the administration's purpose, but strong weight should be given to the interests of the holder of property rights. Here, the banks were given permission because the costs to the banks were disproportionate to the benefit to the company.[104] The moratorium lasts for one year, but can be extended with the administration.[105]

The duties of an administrator in Schedule B1, paragraph 3 are theoretically meant to be exercised for the benefit of the creditors as a whole.[106] However the administrator's duties on paper lie in tension with how, and by whom, an administrator is appointed. The holder of a floating charge, which covers substantially all of a company's property (typically the company's bank), has an almost absolute right to select the administrator. Under Schedule B1, paragraph 14, it may appoint the administrator directly, and can do so out of court. The company need not be technically insolvent, so long as the terms of the floating charge allow appointment. The directors or the company may also appoint an administrator out of court,[107] but must give five days' notice to any floating charge holder,[108] who may at any point intervene and install his own preferred candidate.[109] The court can, in law, refuse the floating charge holder's choice of administrator because of the 'particular circumstances of the case', though this will be rare. Typically banks wish to avoid the spotlight and any effect on their reputation, and so they suggest that company directors appoint the administrator from their own list.[110] Other creditors may also apply to court for an administrator to be appointed, although once again, the floating charge holder may intervene.[111] In this case, the court will grant the petition for appointment of an administrator only if, first, the company "is or is likely to become unable to pay its debts" (identical to IA 1986 section 123) and "the administration order is reasonably likely to achieve the purpose of administration."[112] In Re Harris Simons Construction Ltd Hoffmann J held that 'likely to achieve the purpose of administration' meant a test lower than balance of probabilities, and more like whether there was a 'real prospect' of success or a 'good arguable case' for it. So here the company was granted an administration order, which led to its major creditor granting funding to continue four building contracts.[113]

Once in place, the first task of an administrator is to make proposals to achieve the administration objectives. These should be given to the registrar and unsecured creditors within 10 weeks, followed by a creditor vote to approve the plans by simple majority.[114] If creditors do not approve the court may make an order as it sees fit.[115] However, before then under Schedule B1, paragraph 59 the administrator can do 'anything necessary or expedient for the management of the affairs, business and property of the company'.[116] In Re Transbus International Ltd Lawrence Collins J made the point that the rules on administration were intended to be "a more flexible, cheaper and comparatively informal alternative to liquidation" and so with regard to doing what is expedient "the fewer applications which need to be made to the court the better."[117] This means that an administrator can sell the whole assets of a company immediately, making the eventual creditors' meeting redundant.[118] Because of this and out of court appointments, since 2002, "pre-packaged administrations" became increasingly popular. Typically the company directors negotiate with their bank, and a prospective administrator, to sell the business to a buyer immediately after entering administration. Often the company's directors are the buyers.[119] The perceived benefits of this practice, originating in the 1980s in the United States,[120] is that a quick sale without hiring lawyers and expending time or business assets through formalities, can be effected to keep the business running and employees in their jobs. The potential downside is that because a deal is already agreed among the controlling interested parties (directors, insolvency practitioners and the major secured creditor) before broader consultation, unsecured creditors are given no voice, and will recover almost none of their debts.[121] In Re Kayley Vending Ltd, which concerned an in-court appointed administrator,[122] HH Judge Cooke held that a court will ensure that applicants for a prepack administration provide enough information for a court to conclude that the scheme is not being used to unduly disadvantage unsecured creditors. Moreover, while the costs of arranging the prepack before entering administration will count for the purpose of administrator's expenses, it is less likely to do so if the business is sold to the former management. Here the sale of a cigarette vending machine business was to the company's competitors, and so the deal was sufficiently "arm's length" to raise no concern. In their conduct of meetings, the Court of Appeal made clear in Revenue and Customs Commissioners v Maxwell that administrators appointed out of court will be scrutinised in the way they treat unsecured creditors. Here the administrator did not treat the Revenue as having sufficient votes against the company's management buyout proposal, but the court substituted its judgment and stated the number of votes allowed should take account of events all the way in the run up to the meeting, including in this case the Revenue's amended claim for unlawful tax deductions to the managers' trust funds and loans to directors.[123]

This wide discretion of the administrator to manage the company is reflected also in paragraph 3(3)-(4), whereby the administrator may choose between which result (whether saving the company, selling the business, or winding down) "he thinks" subjectively is most appropriate. This places an administrator in an analogous position to a company director.[124] Similarly, further binding duties allow a broad scope for the administrator to exercise good business judgment. An administrator is subject to a duty to perform her functions as 'quickly and efficiently as is reasonably practicable',[125] and must also not act so as to 'unfairly harm' a creditor's interests. In Re Charnley Davies Ltd (No 2) the administrator sold the insolvent company's business at an allegedly undervalued price, which creditors alleged breached his duty to not unfairly harm them.[126] Millett J held the standard of care was not breached, and was the same standard of care as in professional negligence cases of an "ordinary, skilled practitioner". He emphasised that courts should not judge decisions which may turn out sub-optimal with the benefit of hindsight. Here the price was the best possible in the circumstances. Further, in Oldham v Kyrris it was held that creditors may not sue administrators directly in their own capacity, because the duty is owed to the company.[127] So a former employee of a Burger King franchise with an equitable charge for £270,000 for unpaid wages could not sue the administrator directly, outside the terms of the statutory standard, unless responsibility had been directly assumed to him.[128]

Receivership

[edit]For businesses where floating charges were created before 2003, and in eight types of corporate insolvencies in the Insolvency Act 1986, sections 72B to 72GA, an older procedure of administrative receivership remains available. These companies are capital market investments; public-private partnerships with step in rights; utility projects; urban regeneration projects; large project finance with step in rights;[129] financial market, system and collateral security charges; registered social landlords; and rail and water companies. Until the Enterprise Act 2002, creditors who had contracted for a security interest over a whole company could appoint their own representative to seize and take a company's assets, owing minimal duties to other creditors. Initially this was a right based purely in the common law of property. The Law of Property Act 1925 gave the holder of any mortgage an incidental power to sell the secured property once the power became exercisable. The receiver was appointable and removable only by, and was the sole the agent of, the mortgagee.[130] In companies, secured lenders who had taken a floating charge over all the assets of a company also contracted for the right upon insolvency to manage the business: the appointed person was called a "receiver and manager" or an "administrative receiver".[131] The Insolvency Act 1986 amended the law so as to codify and raise the administrative receiver's duties. All receivers had a duty to keep and show accounts,[132] and administrative receivers had to keep unsecured creditors informed, and file a report at Companies House.[133] By default, he would be personally liable for contracts that he adopted while he ran the business.[134] For employment contracts, he could not contract out of liability, and had to pay wages if he kept employees working for over 14 days.[135] However, the administrative receiver could always be reimbursed for these costs out of the company's assets,[136] and he would have virtually absolute management powers to control the company in the sole interest of the floating charge holder.

The basic duty of the receiver was to realise value for the floating charge holder, although all preferential debts, or those with priority, would have to be paid.[137] For other unsecured creditors, the possibility of recovering money was remote. The floating charge holder owed no duty to other creditors with regard to the timing of the appointment of a receiver, even if it could have an effect on negotiations for refinancing the business.[138] It was accepted that a receiver had a duty to act only for the proper purpose of realising debts, and not for some ulterior motive. In Downsview Nominees Ltd v First City Corp Ltd,[139] a company had given floating charges to two banks (Westpac first, and First City Corp second). The directors, wishing to install a friendly figure in control asked Westpac to assign its floating charge to their friend Mr Russell, who proceeded to run the business with further losses of $500,000, and refused to pass control to First City Corp, even though they offered the company discharge of all the money owed under the first debenture. The Privy Council advised that Mr Russell, as administrative receiver, had acted for an improper purpose by refusing this deal. A further case of breach of duty occurred in Medforth v Blake[140] where the administrative receiver of a pig farm ignored the former owner's advice on how to get discounts on pig food of £1000 a week. As a result, larger debts were run up. Sir Richard Scott VC held this was a breach of an equitable duty of exercising due diligence. However, a more general duty to creditors was tightly constrained, and general liability for professional negligence was denied to exist. In Silven Properties Ltd v Royal Bank of Scotland[141] a receiver of a property business failed to apply for planning permission on houses that could have significantly raised their value, and did not find tenants for the vacant properties, before selling them. It was alleged that the sales were at an undervalue, but the Court of Appeal held that the receiver's power of sale was exercisable without incurring any undue expense. Everything was subordinate to the duty to the receiver to realise a good price.[142] In this respect, an administrator is not capable of disregarding other creditors, at least in law. One of the reasons for the partial abolition of administrative receivership was that after the receiver had performed his task of realising assets for the floating charge holder, very little value was left in the company for other creditors because it appeared to have fewer incentives to efficiently balance all creditors' interests.[143] Ordinarily, once the receiver's work was done, the company would go into liquidation.

Liquidation

[edit]

Liquidation is the final, most frequent, and most basic insolvency procedure. Since registered companies became available to the investing public, the Joint Stock Companies Winding-Up Act 1844 and all its successors contained a route for a company's life to be brought to an end. The basic purpose of liquidation is to conclude a company's activities and to sell off assets (i.e. "liquidate", turn goods into "liquid assets" or money) to pay creditors, or shareholders if any value remains. Either the company (its shareholders or directors) can initiate the process through a "voluntary liquidation", or the creditors can force it through a "compulsory liquidation". In urgent circumstances, a provisional liquidation order can also be granted if there is a serious threat to dissipation of a company's assets: in this case, a company may not be notified.[144] By contrast, a voluntary liquidation begins if the company's members vote to liquidate with a 75 per cent special resolution.[145] If the directors can make a statutory declaration that the company is solvent, the directors or shareholders remain in control,[146] but if the company is insolvent, the creditors will control the voluntary winding up.[147] Otherwise, a "compulsory liquidation" may be initiated by either the directors, the company, some shareholders or creditors bringing a petition for winding up to the court.[148] In principle, almost any member (this is usually shareholders, but can also be anyone registered on the company's member list) can bring a petition for liquidation to begin, so long as they have held shares for over six months, or there is only one shareholder.[149] In Re Peveril Gold Mines Ltd[150] Lord Lindley MR held that a company could not obstruct a member's right to bring a petition by requiring that two directors consented or the shareholder had over 20 per cent of share capital. A member's right to bring a petition cannot be changed by a company constitution. However, in Re Rica Gold Washing Co[151] the Court of Appeal invented an extra-statutory requirement that a member must have a sufficient amount of money (£75 was insufficient) invested before bringing a petition.[152] For creditors to bring a petition, there must simply be proof that the creditor is owed a debt that is due. In Mann v Goldstein[153] the incorporated hairdressing and wig business, with shops in Pinner and Haverstock Hill, of two married couples broke down in acrimony. Goldstein and his company petitioned for winding up, claiming unpaid directors fees and payment for a wig delivery, but Mann argued that Goldstein had received the fees through ad hoc payments and another company owed money for the wigs. Ungoed Thomas J held the winding-up petition was not the place to decide the debt actually existed, and it would be an abuse of process to continue.[154]

Apart from petitions by the company or creditors, an administrator has the power to move a company into liquidation, carrying out an asset sale, if its attempts at rescue come to an end.[155] If the liquidator is not an administrator, he is appointed by the court usually on the nomination of the majority of creditors.[156] The liquidator can be removed by the same groups.[157] Once in place, the liquidator has the power to do anything set out in sections 160, 165 and Schedule 4 for the purpose of its main duty. This includes bringing legal claims that belonged to the company. This is to realise the value of the company, and distribute the assets. Assets must always be distributed in the order of statutory priority: releasing the claims of fixed security interest holders, paying preferential creditors (the liquidator's expenses, employees and pensions, and the ring fenced fund for unsecured creditors),[158] the floating charge holder, unsecured creditors, deferred debts, and finally shareholders.[159] In the performance of these basic tasks, the liquidator owes its duties to the company, not individual creditors or shareholders.[160] They can be liable for breach of duty by exercising powers for improper purposes (e.g. not distributing money to creditors in the right order,[161]) and may be sued additionally for negligence.[162] As a person in a fiduciary position, he may have no conflict of interest or make secret profits. Nevertheless, liquidators (like administrators and some receivers) can generally be said to have a broad degree of discretion about the conduct of liquidation. They must realise assets to distribute to creditors, and they may attempt to maximise these by bringing new litigation, either to avoid transactions entered into by the insolvent company, or by suing the former directors.

Increasing assets

[edit]

If a company has gone into an insolvency procedure, administrators or liquidators should aim to realise the greatest amount in assets to distribute to creditors.[163] The effect is to alter orthodox private law rules regarding consideration, creation of security and limited liability. The freedom to contract for any consideration, adequate or not,[164] is curtailed when transactions are made for an undervalue, or whenever it comes after the presentation of a winding up petition.[165] The freedom to contract for any security interest[166] is also restricted, as a company's attempt to give an undue preference to one creditor over another, particularly a floating charge for no new money, or any charge that is not registered, can be unwound.[167] Since the Cork Report's emphasis on increasing director accountability, practitioners may sue directors by summary procedure for breach of duties, especially negligence or conflicts of interest. Moreover, and encroaching on limited liability and separate personality,[168] a specific, insolvency related claim was created in 1986 named wrongful trading, so if a director failed to put a company into an insolvency procedure, and ran up extra debts, when a reasonable director would have, he can be made liable to contribute to the company's assets. Intentional wrongdoing and fraud is dealt with strictly, but proof of a mens rea is unnecessary in the interest of preventing unjust enrichment of some creditors at others' expense, and to deter wrongdoing.

Voidable transactions

[edit]There are three main claims to unwind substantive transactions that could unjustly enrich some creditors' at the expense of others. First, the Insolvency Act 1986 section 127 declares every transaction void which is entered after the presentation of a winding up petition, unless approved by a court. In Re Gray's Inn Construction Co Ltd[169] Buckley LJ held that courts would habitually approve all contracts that were plainly beneficial to a company entered into in good faith in the ordinary course of business. The predominant purpose of the provision is to ensure unsecured creditors are not prejudiced, and the company's assets are not unduly depleted. However, in Re Gray's Inn because a host of transactions honoured by the company's bank, in an overdrawn account, between the presentation and the winding up petition were being granted, this meant unprofitable trading. So, the deals were declared void.[170] In Hollicourt (Contracts) Ltd v Bank of Ireland, the Court of Appeal held that a bank itself which allows overpayments will not be liable to secondarily creditors if transactions are subsequently declared void. It took the view that a bank is not unjustly enriched, despite any fees for its services the bank may receive.[171] Second, under IA 1986 section 238, transactions at an undervalue may be avoided regardless of their purpose, but only up to two years before the onset of insolvency.[172] For example, in Phillips v Brewin Dolphin Bell Lawrie Ltd[173] the liquidators of an insolvent company, AJ Bekhor Ltd, claimed to rescind the transfer of assets to a subsidiary, whose shares were then purchased by the investment management house Brewin Dolphin for £1. The only other consideration given by Brewin Dolphin was the promise to carry out a lease agreement for computers, which itself was likely to be unwound and therefore worthless. The House of Lords held that the total package of connected transactions could be taken into account to decide whether a transaction was undervalued or not, and held that this one was.