Western Azerbaijan (irredentist concept)

Western Azerbaijan (Azerbaijani: Qərbi Azərbaycan) is an irredentist propaganda and revisionism concept that is used in the Republic of Azerbaijan mostly to refer to the territory of Armenia. Azerbaijani officials have falsely claimed that the territory of the modern Armenian republic were lands that once belonged to Azerbaijanis.[1][2] Its claims are primarily hinged over the contention that the current Armenian territory was under the rule of various Turkic tribes, empires and khanates from the Late Middle Ages until the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828) signed after the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828. The concept has received official endorsement by the government of Azerbaijan, and has been used by its current president, Ilham Aliyev, who, since around 2010, has made regular reference to "Irevan" (Yerevan), "Göyçə" (Lake Sevan) and "Zangazur" (Syunik) as once and future "Azerbaijani lands".[3] The irredentist concept of "Western Azerbaijan" is associated with other irredentist claims promoted by Azerbaijani officials and academics, including the "Goyche-Zangezur Republic" and the "Republic of Irevan."[4]

After Aliyev was nominated in 2018 by the New Azerbaijan Party as presidential candidate, he called for "the return of Azerbaijanis to these lands" and establishing this as "our political and strategic goal, and we must gradually approach it." [5][6][7] In December 2022, Azerbaijan initiated its "Great Return" campaign which ostensibly promotes the settlement of ethnic Azerbaijanis who once lived in Armenia and Nagorno-Karbakh.[8][9] At his inauguration speech in December 2022, President Aliyev said "Present-day Armenia is our land. When I repeatedly said this before, they tried to object and allege that I have territorial claims. I am saying this as a historical fact. If someone can substantiate a different theory, let them come forward."[10][11]

Since the end of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, Azerbaijan has increasingly promoted expansionist claims to Armenian territory and in particular Syunik.[12][13] These manufactured territorial claims are part of Azerbaijan's strategy to weaken Armenia's requests for a special status for Armenians living in Nagorno-Karabakh[14] and achieve pan-Turkic territorial ambitions.[13][15][16]

Term, background and usage

The term "Western Azerbaijan" was originally a colloquialism used by some Azerbaijani refugees to refer to the Armenian SSR of the Soviet Union.[3] In the late 1990s, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the establishment of the independent republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan, the term began to assume a more geopolitical meaning "as a revivalist project recovering the history of this population after displacement".[3] As a return to Armenia was never considered to be politically feasible, those Azerbaijani refugees integrated into mainstream Azerbaijani society, with the community fading away over time.[3] However, as the historian and political scientist Laurence Broers explains, the historical geography of an "Azerbaijani palimpsest" underneath the soil of modern Armenia remained alive.[3] Although Azerbaijan attempts to equate the rights of "Western Azerbaijan" with those of Karabakh in its negotiations with Armenia, there are significant differences, including the fact that Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh have lived there until very recently.[14][17] Armenian prime minister Pashinyan has responded by saying it would be more accurate to compare "Western Azerbaijanis" to Armenians who once lived in Azerbaijan's exclave of Nakhchivan.[14]

Broers describes "Western Azerbaijanism" as a geopolitical vision that absorbs a modern Armenian territoriality in its entirety" in which "Armenians are portrayed as usurping interlopers with neither an indigenous state nor a culture of their own."[18] According to Broers, the false idea that "[...] Armenians arrived in the Caucasus only in the 19th century, specifically onto ‘Azerbaijani lands’, has been gathering pace in school curricula, maps, and official speeches for at least a decade, and has become mainstream over the last two years."[19] According to Harvard University professor, Christina Maranci, Azerbaijan uses "the propaganda of a “Western Azerbaijan” in place of the Republics of Armenia and Artsakh."[20]

Within Azerbaijani historiography, the Erivan Khanate has undergone the same type of transformation like the historic entity of Caucasian Albania before it.[3] Azerbaijani historiography regards the Erivan Khanate as an "Azerbaijani state" which was populated by autochthonous Azerbaijani Turks, and its soil is sacralised, as Broers adds, "as the burial ground of semi-mythological figures from the Turkic pantheon".[3] Within the same Azerbaijani historiography, the terms "Azerbaijani Turk" and "Muslim" are used interchangeably, even though contemporary demographic surveys differentiate "Muslims" into Persians, Shia and Sunni Kurds and Turkic tribes.[3]

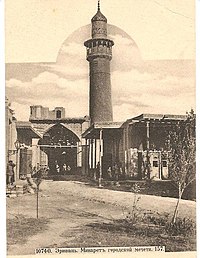

According to Broers, catalogues of "lost Azerbaijani heritage" portray an array of "Turkic palimpsest beneath almost every monument and religious site in Armenia – whether Christian or Muslim".[3] Additionally, from around 2007, standard maps of Azerbaijan started to show Turkic toponyms printed in red underneath the Armenian ones on the major part of Armenia which it shows.[3] In terms of rhetoric, as Broers narrates, the Azerbaijani palimpsest beneath Armenia "reaches into the future as a prospective territorial claim".[3] The Armenian capital of Yerevan is particularly focused by this narrative; the Yerevan Fortress and Sardar Palace, which had been demolished by the Soviets during their building of the city, have become "widely disseminated symbols of lost Azerbaijani heritage recalling the fetishised contours of a severed body part".[21] Similarly, Lake Sevan is also often targeted, wherein its referred to by its Azerbaijani name Göyçə.[21]

From the mid-2000s, the concept of a "Western Azerbaijan" was merged into renewed interest of the khanates of the Caucasus, in, what Broers explains as "wide-ranging fetishisation" of the Erivan Khanate as a "historically Azerbaijani entity".[3] Azerbaijani nationalism has been redefined to include viewing Armenian territory as Azerbaijani "ancestral lands."[22] In 2003, Azerbaijani Defense Minister Safar Abiyev said "The Armenian state was created on the occupied Azeri lands with the area of 29,000 square kilometers.”[23] The Azerbaijani Defense Ministry spokesman Colonel Ramiz Melikov made more extreme comments in 2004: “In the next 25–30 years there will be no Armenian state in the South Caucasus. This nation has been a nuisance for its neighbors and has no right to live in this region. Present-day Armenia was built on historical Azerbaijani lands. I believe that in 25–30 years these territories will once again come under Azerbaijan's jurisdiction.”[23]

In 2005, an organization called "Return to Western Azerbaijan" led by Rizvan Talybov, was created and declared that it would lobby for the creation of an autonomous republic on Armenian territory and later the creation of a government in exile.[24] The Azerbaijani government has produced publications and videos that depict modern-day Armenia as "Western Azerbaijan":[25][26][27] for instance, a 2007 catalogue produced by the Azerbaijani Ministry of Culture and Tourism opens with a map of “The Ancient Turkish–Oghuz land—Western Azerbaijan (Present-Day Republic of Armenia).”[25][26] In 2018, the Azerbaijani government started to promote the idea that the capital of Armenia has Azerbaijani origins. Aliyev said "The younger generation, and the entire world, should know about [the history of Erivan]. I am glad that scientific work is being done, films are being produced, exhibitions are organized about the history of our ancestral lands. In the years ahead we must be more active in this direction, and presentations and exhibitions should be organized in various corners of the world."[27]

Developments since the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War

Since the end of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, Azerbaijan has increasingly promoted irredentist claims to Armenian territory which it describes as "Western Azerbaijan".[28][29][30][15] These manufactured territorial claims are part of Azerbaijan's strategy to weaken Armenia's requests for a special status for Armenians living in Artsakh/Nagorno-Karabakh.[14] Benyamin Poghosyan, an analyst and head of the Center for Political and Economic Strategic Studies in Yerevan wrote “Azerbaijan uses this concept as a stick to force Armenia to drop its demands for international presence in Nagorno-Karabakh.”[14][31]

After Azerbaijan attacked Armenia in September 2022,[32] pro-government media and certain Azerbaijani and Turkish officials briefly promoted the irredentist concept of the "Goycha-Zangazur Republic" which claims all of southern Armenia and whose aim is "to reunite the Turkish world."[15][16] Azerbaijani member of parliament Hikmat Babaoghlu condemned the idea, arguing that it weakens Azerbaijan's public case to create the Zangezur corridor.[15] According to Broers, Azerbaijan's irredentism has shifted the focus of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict from self-determination and majority-minority relations to inter-state relations.[22]

In 2020, Gafar Chahmagli an ethnically Azerbaijani professor of the University of Kayseri said "the main goal of the Republic of Western Azerbaijan (Irevan) [...] is return [to Azerbaijan] all historic lands, including Yerevan, Zangebasar, Goichu, Zangezur, Gyumri, Drlayza [Daralageaz?], and all remaining historical lands within the border of Armenia."[33][34][35]

In July 2021, Azerbaijan reorganized the organization of its internal economic regions which included a new region, bordering Syunik (Armenia), named “Eastern Zangezur,” which implied that there is a “Western Zangezur” — that is Syunik. This was confirmed by President Aliyev in a speech a few days later: “Yes, Western Zangezur is our ancestral land […] we must return there and we will return. No one can stop us."[22][36] In December 2022, the Azerbaijan government inaugurated its "Great Return" program, which ostensibly promotes the settlement of ethnic Azerbaijanis who once lived in Armenia and Nagorno-Karbakh.[8][9] As part of this program, a natural gas pipeline will be built between Agdam and Stapanakert which will begin operation in 2025 which is also when the Russian peacekeeping forces' mandate in Nagorno-Karbakh ends.[37]

On March 10, 2023, Azerbaijani President Aliyev said that “Armenia lost its chance to become an independent state,” alleging that Armenia had committed acts of aggression against Azerbaijan.[38]

On March 16, 2023, Azerbaijani President Aliyev made a speech in which he repeatedly described Armenian territory as "Western Azerbaijan" during the summit of the Heads of State of the Organization of Turkic States. Aliyev also said that "The decision of the Soviet government in November 1920 to separate West Zangezur, our historical land, from Azerbaijan and hand it over to Armenia led to the geographical separation of the Turkic world."[39] The Armenian Foreign Ministry responded by describing the speech as "a clear manifestation of territorial claims against the Republic of Armenia and the preparation of another aggression."[40][41]

History

The present-day territory of Armenia, along with the western part of Azerbaijan, including Nakhchivan were historically part of the Armenian Highlands and Eastern Armenia.[43][44] The toponym "Zangezur" that Azerbaijan uses is derived from the name of a district created by the Russian Empire in 1868 as part of the Yelizavetpol governorate.[22] The term covers an area including what is today the southern part of Armenia. Syunik, the Armenian name, is an older term dating back to antiquity.[22]

The area formed part of the ancient Kingdom of Armenia after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire, with control over the region later being contested by the Roman Empire and in turn the Parthian and Sassanid Empires in Persia. In the Middle Ages, the area was controlled variously by Oghuz Turkic Seljuks, Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu before eventually falling into the hands of the Safavid Empire.

Under the Iranian Safavids, the area that constitutes the bulk of the present-day Republic of Armenia, was organized as the Erivan Province. The Erivan Province also had Nakhchivan as one of its administrative jurisdictions. A number of the Safavid era governors of the Erivan Province were of Turkic origin. Together with the Karabagh province, the Erivan Province comprised Iranian Armenia.[45][46]

Iranian ruler Nader Shah (r. 1736–1747) later established the Erivan Khanate (i.e. province); from then on, together with the smaller Nakchivan Khanate, these two administrative entities constituted Iranian Armenia.[47] In the Erivan Khanate, the Armenian citizens had partial autonomy under the immediate jurisdiction of the melik of Erevan.[48] In the Qajar era, members of the royal Qajar dynasty were appointed as governors of the Erivan khanate, until the Russian occupation in 1828.[49] The heads of the provincial government of the Erivan Khanate were thus directly related to the central ruling dynasty.[50]

In 1828, per the Treaty of Turkmenchay, Iran was forced to cede the Erivan and Nakhchivan Khanates to the Russians. These two territories, which had constituted Iranian Armenia prior to 1828, were added together by the Russians and then renamed into the "Armenian Oblast".

According to journalist Thomas de Waal, a few residents of Vardanants Street recall a small mosque being demolished in 1990.[51] Geographical names of Turkic origin were changed en masse into Armenian ones,[52] a measure seen by some as a method to erase from popular memory the fact that Muslims had once formed a substantial portion of the local population.[53] According to Husik Ghulyan's study, in the period 2006–2018, more than 7700 Turkic geographic names that existed in the country have been changed and replaced by Armenian names.[54] Those Turkic names were mostly located in areas that previously were heavily populated by Azerbaijanis, namely in Gegharkunik, Kotayk and Vayots Dzor regions and some parts of Syunik and Ararat regions.[54]

Demographic basis

Until the mid-fourteenth century, Armenians had constituted a majority in Eastern Armenia.[44] At the close of the fourteenth century, after Timur's campaigns, Islam had become the dominant faith, and Armenians became a minority in Eastern Armenia.[44] After centuries of constant warfare on the Armenian Plateau, many Armenians chose to emigrate and settle elsewhere. Following Shah Abbas I's massive deportation (see Great Surgun) of predominantly Armenians in 1604–05,[55] their numbers dwindled even further.

Some 80% of the population of Iranian Armenia were Muslims (Persians, Turkics, and Kurds) whereas Christian Armenians constituted a minority of about 20%.[56] As a result of the Treaty of Gulistan (1813) and the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), Iran was forced to cede Iranian Armenia (which also constituted the present-day Republic of Armenia), to the Russians.[47][57]

After the Russian administration took hold of Iranian Armenia, the ethnic make-up shifted, and thus for the first time in more than four centuries, ethnic Armenians started to form a majority once again in one part of historic Armenia.[58] The new Russian administration encouraged the settling of ethnic Armenians from Iran proper and Ottoman Turkey. As a result, by 1832, the number of ethnic Armenians had matched that of the Muslims.[56] Only after the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, which brought another influx of Turkish Armenians, were ethnic Armenians once again the solid majority in Eastern Armenia.[59] Nevertheless, the city of Yerevan remained having a Muslim majority up to the twentieth century.[59] According to the traveller H. F. B. Lynch, the city of Erivan was about 50% Armenian and 50% Muslim (Tatars[a] i.e. Azeris and Persians) in the early 1890s.[48]

According to the Russian census of 1897, about 300,000 Tatars populated the Russian Empire's Erivan Governorate[62] (roughly corresponding to most of present-day central Armenia, Iğdır Province of Turkey, present-day Azerbaijani Nakhchivan, but excluding Syunik and most of northern Armenia). They formed the majority in four of the governorate's seven districts (including Igdyr and Nakhchivan, which are not part of Armenia today and Sharur-Daralayaz which is mostly in Azerbaijan) and were nearly as many as the Armenians in Yerevan (42.6% against 43.2%).[63] At the time, Eastern Armenian cultural life was centered more around the holy city of Echmiadzin, seat of the Armenian Apostolic Church.[64]

Reactions

Several organizations and political analysts have condemned Azerbaijan's territorial claims, stating that they post a threat to security in the region or to the Armenian people.

![]() European Parliament – issued two resolutions in 2021 and 2022, condemning Azerbaijan's ongoing invasion of Armenia in which they described the aggressive and irredentist territorial statements by Azerbaijani authorities referring to Armenian territory as ancestral land as "worrying" and "undermin[g] the efforts towards security and stability in the region."[65] The European Parliament also encouraged Armenia to seek alternative security alliances considering CSTO's inaction during Azerbaijan's invasion.[66][67]

European Parliament – issued two resolutions in 2021 and 2022, condemning Azerbaijan's ongoing invasion of Armenia in which they described the aggressive and irredentist territorial statements by Azerbaijani authorities referring to Armenian territory as ancestral land as "worrying" and "undermin[g] the efforts towards security and stability in the region."[65] The European Parliament also encouraged Armenia to seek alternative security alliances considering CSTO's inaction during Azerbaijan's invasion.[66][67]

![]() Council of Europe – issued a report in which it described Azerbaijan as "a party keen to employ hate rhetoric and even denying Armenia’s territorial integrity."[68]

Council of Europe – issued a report in which it described Azerbaijan as "a party keen to employ hate rhetoric and even denying Armenia’s territorial integrity."[68]

Armenian National Committee of America — Alex Galitsky, a program director of the organization, argued that Azerbaijan’s ongoing incursions into sovereign Armenian territory is indistinguishable from Russia's invasion of Ukraine. He wrote "By violating Armenia’s sovereignty, Baku has demonstrated that this [Nagorno-Karabakh] conflict was never truly about the principle of territorial integrity for Azerbaijan [and]... If Washington wants to demonstrate consistency in its response to authoritarian expansionism, that must begin with an immediate halt to all military assistance to Azerbaijan..."[69]

See also

- Azerbaijanis in Armenia

- Khanates of the Caucasus

- Erivan Khanate

- Shoragel sultanate

- Shamshadil sultanate

- History of Azerbaijan

- Whole Azerbaijan

- Anti-Armenian sentiment in Azerbaijan

Notes

- ^ The term "Tatars", employed by the Russians, referred to Turkish-speaking Muslims (Shia and Sunni) of Transcaucasia.[60] Unlike Armenians and Georgians, the Tatars did not have their own alphabet and used the Perso-Arabic script.[60] After 1918 with the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, and "especially during the Soviet era", the Tatar group identified itself as "Azerbaijani".[60] Prior to 1918 the word "Azerbaijan" exclusively referred to the Iranian province of Azarbayjan.[61]

References

- ^ "Present-day Armenia located in ancient Azerbaijani lands - Ilham Aliyev". News.Az. October 16, 2010. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ "Statement in Response to the Open Letter sent by the Rabbinical Center of Europe to the President and Prime Minister of Armenia". Lemkin Institute. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Broers 2019, p. 117.

- ^ "The rise and fall of Azerbaijan's "Goycha-Zangazur Republic"". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ Broers 2019, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Узел, Кавказский. "Власти Армении возмутились словами Алиева об исторических землях Азербайджана". Кавказский Узел (in Azerbaijani). Retrieved 2023-06-25.

"Erivan is our historical land, and we, Azerbaijanis, must return to these lands. This is our political and strategic goal, and we must gradually approach it".

- ^ "Ильхам Алиев назвал стратегической целью азербайджанцев "возвращение" Еревана" [Ilham Aliyev called the strategic goal of the Azerbaijanis the "return" of Yerevan]. Interfax.ru (in Russian). 2018-02-08. Retrieved 2023-06-25.

Azerbaijanis should gradually approach their strategic goal of "returning" Yerevan to themselves, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev said. 'Yerevan is our historical land, and we Azerbaijanis must return to these lands. This is our political and strategic goal, and we must gradually approach it,' Aliyev said at the VI Congress of the ruling Yeni Azerbaijan Party.

- ^ a b "Aliyev: "The great return begins"". commonspace.eu. Retrieved 2023-01-25.

- ^ a b "Azerbaijan seeks "Great Return" of refugees to Armenia". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-25.

- ^ Joshua Cucera (17 January 2023). "Azerbaijan seeks "Great Return" of refugees to Armenia". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ "Ilham Aliyev viewed conditions created at administrative building of Western Azerbaijan Community". president.az, official website of the President of Azerbaijan Republic. 24 December 2022. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ "Is Azerbaijan planning a long-term presence in Armenia?". Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank. 2022-09-26. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

An Azerbaijani historiographic tradition suggesting Armenians arrived in the Caucasus only in the 19th century, specifically onto 'Azerbaijani lands', has been gathering pace in school curricula, maps, and official speeches for at least a decade, and has become mainstream over the last two years

- ^ a b "Red Flag Alert for Genocide - Azerbaijan in Armenia". Lemkin Institute. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- ^ a b c d e Kucera, Joshua (Mar 29, 2023). "Baku pushes rights of "Western Azerbaijan" in negotiations with Yerevan". Eurasianet.

- ^ a b c d "The rise and fall of Azerbaijan's "Goycha-Zangazur Republic"". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ a b Nagihan, Ece (2022-09-22). "Turkey is the First State to Recognize the Goyce-Zengezur Turkish Republic!". Expat Guide Turkey. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ amartikian (2023-03-15). ""Azerbaijan has territorial designs on Armenia" - Nikol Pashinyan". English Jamnews. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ Broers 2019, p. 22.

- ^ "Is Azerbaijan planning a long-term presence in Armenia?". Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank. 2022-09-26. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- ^ Topalian, Ruby (2023-08-14). "The Slow Death: Azerbaijan's Armenian Genocide". Trinity News. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

Professor of Armenian Studies at Harvard University Christina Maranci explained Azerbaijan's wider goals: 'If one follows the rhetoric that has come out for years now from the government of Azerbaijan – including the postage stamps celebrating the 'extermination' of Armenians from the region, the propaganda of a 'western Azerbaijan' in place of the Republics of Armenia and Artsakh, and the erasure of Armenian cultural heritage in now-captured lands – it follows that the goal is complete elimination of Armenian presence in the region, as human rights organizations including Genocide Watch began to signal already last year.'

- ^ a b Broers 2019, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d e "Perspectives | Augmented Azerbaijan? The return of Azerbaijani irredentism". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ a b Suny, Ronald Grigor (2010-01-01). "The pawn of great powers: The East–West competition for Caucasia". Journal of Eurasian Studies. 1 (1): 10–25. doi:10.1016/j.euras.2009.11.007. ISSN 1879-3665. S2CID 153939076.

- ^ "Azerbaijan: Former Presidential Adviser Discusses Regionalism In Politics". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ a b Alakbarli, Aziz (2007). The Monuments of Western Azerbaijan (PDF). Baku: Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Azerbaijani Republic.

- ^ a b Broers, Laurence; Toal, Gerard (2013-05-01). "Cartographic Exhibitionism?". Problems of Post-Communism. 60 (3): 16–35. doi:10.2753/PPC1075-8216600302. ISSN 1075-8216. S2CID 154163316.

- ^ a b "Azerbaijan mounts exhibition showcasing Erivan Khanate". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ "Perspectives | Augmented Azerbaijan? The return of Azerbaijani irredentism". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ Boy, Ann-Dorit (2023-01-18). "Blockade in the Southern Caucasus: "There Is Every Reason to Expect More Violence This Year"". Der Spiegel. ISSN 2195-1349. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ "Azerbaijan seeks "Great Return" of refugees to Armenia". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ Poghosyan, Dr Benyamin (2023-03-23). "What next in Armenia-Azerbaijan negotiations". The Armenian Weekly. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ "Armenia-Azerbaijan tensions: Distracted by Ukraine, Russia is losing its influence in South Caucasus". Firstpost. 2023-01-10. Retrieved 2023-01-11.

- ^ Hakan Yavuz, M; M. Gunter (2023). The Karabakh Conflict Between Armenia and Azerbaijan: Causes & Consequences (978-3-031-16261-9 ed.). palgrave macmillan. p. 112. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-16262-6. ISBN 978-3-031-16261-9. S2CID 254072350.

- ^ Goble, Paul (2020-05-11). "Western Azerbaijan Republic Declared By Professor In Turkey: Government In Exile To Be Formed – OpEd". Eurasia Review. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ "The Republic of West Azerbaijan (Erevan) was declared in exile". www.turan.az. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ "What's the future of Azerbaijan's "ancestral lands" in Armenia?". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ "Armenia and Azerbaijan Are at a Boiling Point. Another Violent Conflict Is Just a Matter of Time". Haaretz. Retrieved 2023-01-25.

- ^ Little, Alex (2023-04-04). "Is there a Way out of the Impasse over Nagorno-Karabakh?". International Policy Digest. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ "Ilham Aliyev attended the Extraordinary Summit of the Organization of Turkic States » Official web-site of President of Azerbaijan Republic". president.az. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ "Statement of MFA of Armenia regarding the false claims and bellicose statements of the President of Azerbaijan". www.mfa.am (in Armenian). Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ "Aliyev's belligerent rhetoric is aimed at resorting to the use of large-scale force against both Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. RA MFA". Time News. 2023-03-16. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ See Hovannisian, Richard G. (1982). The Republic of Armenia, Vol. II: From Versailles to London, 1919-1920. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 192, map 4, 526–529. ISBN 0-520-04186-0.

- ^ A. West, Barbara (2008). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Vol. 1. Facts on File. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8160-7109-8.

- ^ a b c Bournoutian 1980, pp. 11, 13–14.

- ^ Bournoutian 2006, p. 213.

- ^ Payaslian 2007, p. 107.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 1980, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Kettenhofen, Bournoutian & Hewsen 1998, pp. 542–551.

- ^ "Iranians, in order to save the rest of eastern Armenia, heavily subsidized the region and appointed a capable governor, Hosein Qoli Khan, to administer it." -- A Concise History of the Armenian People: (from Ancient Times to the Present), George Bournoutian, Mazda Publishers (2002), p. 215

- ^ Bournoutian 2004, pp. 519–520.

- ^ Myths and Realities of Karabakh War by Thomas de Waal. Caucasus Reporting Service. CRS No. 177, 1 May 2003. Retrieved 31 July 2008

- ^ (in Russian) Renaming Towns in Armenia to Be Concluded in 2007. Newsarmenia.ru. 22

- ^ Nation and Politics in the Soviet Successor States by Ian Bremmer and Ray Taras. Cambridge University Press, 1993; p.270 ISBN 0-521-43281-2

- ^ a b Ghulyan, Husik (2020-12-01). "Conceiving homogenous state-space for the nation: the nationalist discourse on autochthony and the politics of place-naming in Armenia". Central Asian Survey. 40 (2): 257–281. doi:10.1080/02634937.2020.1843405. ISSN 0263-4937. S2CID 229436454.

- ^ Arakel of Tabriz. The Books of Histories; chapter 4. Quote: "[The Shah] deep inside understood that he would be unable to resist Sinan Pasha, i.e. the Sardar of Jalaloghlu, in a[n open] battle. Therefore he ordered to relocate the whole population of Armenia - Christians, Jews and Muslims alike, to Persia, so that the Ottomans find the country depopulated."

- ^ a b Bournoutian 1980, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2015, p. 141.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980, p. 14.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 1980, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Bournoutian, George (2018). Armenia and Imperial Decline: The Yerevan Province, 1900-1914. Routledge. p. 35 (note 25).

- ^ Bournoutian, George (2018). Armenia and Imperial Decline: The Yerevan Province, 1900-1914. Routledge. p. xiv.

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly - Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". www.demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2023-02-20.

- ^ Russian Empire Census 1897

- ^ Thomas de Waal. Black Garden: Armenia And Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press, p. 74. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7

- ^ von Cramon-Taubadel, Viola; Neumann, Hannah; Barrena Arza, Pernando; Villanueva Ruiz, Idoia; Cozzolino, Andrea; Arena, Maria; Marques, Pedro; Rodríguez Ramos, María Soraya; Ștefănuțǎ, Nicolae; Charanzová, Dita; Auštrevičius, Petras; Strugariu, Ramona; Karlsbro, Karin; Hahn, Svenja; Körner, Moritz; Joveva, Irena; Grošelj, Klemen; Chastel, Olivier; Loiseau, Nathalie; Melchior, Karen; Cseh, Katalin; Azmani, Malik; Gheorghe, Vlad; Gahler, Michael; Kelly, Seán; Thun Und Hohenstein, Róża; Łukacijewska, Elżbieta Katarzyna; van Dalen, Peter; Fernandes, José Manuel; Rangel, Paulo; Kalniete, Sandra; Kovatchev, Andrey; Maydell, Eva; Vincze, Loránt; Niedermayer, Luděk; Polčák, Stanislav; Šojdrová, Michaela; Zdechovský, Tomáš; Hetman, Krzysztof; Tomc, Romana; Pospíšil, Jiří; Vandenkendelaere, Tom; Lega, David; Fourlas, Loucas; Wiseler-Lima, Isabel; Jarubas, Adam; Ochojska, Janina; Kympouropoulos, Stelios; Pollák, Peter; Bilčík, Vladimír; Kubilius, Andrius; Lexmann, Miriam; Sagartz, Christian; Weimers, Charlie; Castaldo, Fabio Massimo; Kanko, Assita; Fragkos, Emmanouil. "Joint Motion For a Resolution on prisoners of war in the aftermath of the most recent conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan | RC-B9-0277/2021". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ Kovatchev, Andrey. "Report on EU-Armenia relations | A9-0036/2023". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 2023-03-18.

- ^ sharon (2023-03-18). "Azerbaijani Aggression Condemned by EU Parliament". europeanconservative.com. Retrieved 2023-03-18.

- ^ "Ensuring free and safe access through the Lachin Corridor" (PDF). Parliamentary Council of the Assembly of Europe. 2023-06-22.

- ^ Galitsky, Alex. "Azerbaijan's Aggression Has Forced Armenia Into Russia's Arms". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

Sources

- Bournoutian, George A. (1980). The Population of Persian Armenia Prior to and Immediately Following its Annexation to the Russian Empire: 1826–1832. The Wilson Center, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies.

- Bournoutian, George A. (2004). "Ḥosaynqoli Khan Sardār-E Iravāni". Encycloæedia Iranica. Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 519–520.

- Bournoutian, George A. (2006). A Concise History of the Armenian People (5 ed.). Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. pp. 214–215. ISBN 1-56859-141-1.

- Broers, Laurence (2019). Armenia and Azerbaijan: Anatomy of a Rivalry. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1474450522.

- Kettenhofen, Erich; Bournoutian, George A.; Hewsen, Robert H. (1998). "Erevan". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VIII, Fasc. 5. pp. 542–551.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- Payaslian, Simon (2007). The History of Armenia: From the Origins to the Present. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230608580.