William Robinson Brown

William Robinson Brown | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 17, 1875 Portland, Maine, U.S. |

| Died | August 4, 1955 (aged 80) Dublin, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Brown Company, Woods Division Manager |

| Known for |

|

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Hildreth Burton Smith |

| Children | 5, including Frances H. Townes (nee Brown) |

William Robinson Brown (January 17, 1875 – August 4, 1955), known professionally as W.R. Brown, was an American corporate officer of the Brown Company of Berlin, New Hampshire. An authority on Arabian horses, he was also an influential Arabian horse breeder, and also the founder and owner of the Maynesboro Stud.

After graduating from Williams College, Brown joined the family business, then known as the Berlin Mills Company, and became manager of the Woods Products Division, overseeing the company's woodlands and logging operations. He became an early advocate for sustainable forest management practices, was a member of the New Hampshire Forestry Commission from 1909 until 1952, and served on the boards of several forestry organizations. As chair of the Forestry Commission, Brown helped send sawmills to Europe during World War I to assist the war effort. He was influenced by the Progressive movement, instituting employee benefits such as company-sponsored care for injured workers that predated modern workers' compensation laws. A Republican, he served as a presidential elector for New Hampshire in 1924.

Brown founded the Maynesboro Stud in 1912 with foundation bloodstock from some of the most notable American breeders of Arabian horses. He looked abroad for additional horses, particularly from the Crabbet Arabian Stud, and imported Arabian horses from England, France and Egypt. At its peak, Maynesboro was the largest Arabian horse breeding operation in the United States. In 1929, he wrote The Horse of the Desert, still considered an authoritative work on the Arabian breed. He served as President of the Arabian Horse Club of America from 1918 until 1939. Brown was a remount agent and had a special interest in promoting the use of Arabian horses by the U.S. Army Remount Service. To prove the abilities of Arabians, he organized and participated in a number of endurance races of up to 300 miles (480 km), which his horses won three times, retiring the U.S. Mounted Service Cup. This accomplishment occurred even though The Jockey Club donated $50,000 to the U.S. Army to buy Thoroughbreds that tried but failed to beat the Arabians. Brown's legacy as a horse breeder was significant. Today, the term "CMK", meaning "Crabbet/Maynesboro/Kellogg" is a label for specific lines of "Domestic" or "American-bred" Arabian horses, many of which descend from Brown's breeding program. In 2012, the Berlin and Coös County Historical Society held a 100th anniversary celebration of the stud's founding.

Although Brown family members sold personal assets to keep the Brown Company afloat during the Great Depression, including Brown's dispersal of his herd of Arabian horses in 1933, the business went into receivership in 1934. Brown remained in charge of the Woods Division through the company's second bankruptcy filing in 1941. He retired from the company in 1943 and died of cancer in 1955. His final book, Our Forest Heritage, was published posthumously, and his innovations in forest management became industry standards.

Personal life

[edit]W. R. Brown was born in Portland, Maine, in 1875 to Emily Jenkins Brown and William Wentworth "W. W." Brown.[1] He was the youngest of the couple's three sons,[2] all of whom were avid horsemen.[3] He also had two younger half-brothers.[4] He attended Phillips Andover Academy[1] and Williams College, graduating from the latter in 1897.[5] He was a member of Kappa Alpha Society fraternity who also managed the football and baseball teams at Williams.[1] In 1915, he married Hildreth Burton Smith,[6] the granddaughter of former governor of Georgia, U.S. Senator and Confederate general John B. Gordon. The couple had five children: Fielding, Newell, Brenton, Nancy, and Frances.[7] Brown lived in New Hampshire for the remainder of his life, in Berlin until 1946 and then Dublin. After a long illness, he died of cancer on August 4, 1955,[8] and was buried at the Dublin cemetery. He was survived by his wife, his five grown children, and 15 grandchildren.[7][6]

Brown's family was strongly affiliated with Williams College; W. R. and his two older brothers Herbert ("H. J.") and Orton ("O. B.") all attended Williams, as did sons Fielding and Brenton.[9] Fielding also earned a Ph.D. at Princeton University and returned to Williams as the Charles L. MacMillan Professor of Physics before retiring to become an artist and sculptor.[10] Daughter Frances married Nobel Prize–winning physicist Charles H. Townes and wrote a book, Misadventures of a Scientist's Wife, about her life.[11] Newell attended Princeton and served as the Federal Wages and Hours Administrator for the United States Department of Labor during the Eisenhower administration.[9] Politically aligned with the Republican party, W. R. Brown was a presidential elector for New Hampshire in the 1924 election, voting for Calvin Coolidge.[12]

Brown Company career

[edit]

H. Winslow & Company, later called the Berlin Mills Company, was founded about 1853, and W. W. Brown purchased an interest in 1868.[13] In 1881, the company expanded from lumber into pulp and paper manufacturing.[14] W. W. Brown obtained a controlling interest in the company by 1888,[15] becoming, along with his older two sons, the sole owners by 1907.[13] The corporation's name was changed to the Brown Company in 1917, removing the word "Berlin" because of the conflict with Germany in World War I.[16]

W. R. Brown went to work for the company in 1897 after finishing college. His father, declaring he "wanted no kittens that couldn't catch mice," made W. R. find a job without family help. As a result, Brown started out selling the company's lumber in Portland, Maine, earning nine dollars a week. He was promoted, returned to Berlin, and after a second promotion became the sawmill's night superintendent. In that position, he developed a method of using exhaust steam to heat a pond that thawed and cleaned logs, speeding up mill production during the winter.[17] Promoted to day superintendent, he organized a successful event on September 8, 1900, to break the world's record for lumber cut by the crew of a "one head rig" in an 11-hour shift, producing 221,319 board feet, a record that still stood 85 years later.[18] After this event, he declared that he "qualified with Father as one of the 'kittens'."[19] His father, who had been out of town on the day of the record attempt, reviewed the results, inquired as to the amount of cut lumber that was actually shipped to customers, and then commented, "Hum, that was good."[20] His father promoted Brown to full general manager of the Woods Division in 1902.[19] He was an officer of the corporation,[9] and managed the company's timberlands as director of woods operations until 1943.[1][16] When Brown began his career, the company owned 400,000 acres (160,000 ha) of land.[21] At its peak, the company owned, and Brown supervised, 3,750,000 acres (1,520,000 ha), as many as 40 logging camps, plus an inland fleet of more than 30 boats.[19] The loggers used at least 2500 horses to haul logs,[22] and the company-owned railroad had more than 800 freight cars.[23]

The Brown family was later described as "progressive and ... ahead of their times", and had innovative ideas about wood products manufacturing and scientific forest management.[23][24] During Brown's tenure, the company was one of the first to initiate modern forest management practices and to attempt to conserve the forest for future industry use. He was particularly critical of the damage done by portable sawmills.[25][26] Brown understood that the pulp mills of his time were dependent on locally accessible timber, and concluded that sustainable practices were important to the industry.[27] He built upon the sustainable forestry practices advocated by company forester Austin Cary, who had been recruited from the U.S. Forest Service. In 1919, Brown set up a tree nursery on the north shore of Cupsuptic Lake that researched sustained yield practices[16] and at its peak was the largest tree nursery in the United States.[1] His innovations in forest management became industry standards;[28] researchers at Plymouth State College concluded that he "led the Brown company to international prominence as a source for scientific research and development."[29]

Brown was influenced by the Progressive movement as applied to business.[30] He paid his workers above the prevailing wage, instituted safety programs, hired a doctor to care for loggers in the camps, and, prior to modern workers' compensation laws, had the company pay for hospitalization of injured workers.[1] He also attempted to improve camp conditions for the workers by banning card games and requiring the loggers to take showers, but those particular reform efforts "were not well received."[31] The Brown family took considerable interest in the city of Berlin. Various family members started a public kindergarten, built a community club with a gym, swimming pool, and bowling alley, provided soup to the sick, and gave Christmas presents to local children.[22] Brown himself helped found a number of civic and business self-help organizations including the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests, established in 1901;[32] the New Hampshire Timberlands Owners Association, a fire-protection group established in 1910;[19][28][33] and similar fire-protection groups in Maine and Vermont.[34] He set up a series of effective forest-fire lookout towers, possibly the first in the nation, and by 1917 had helped establish a forest-fire insurance company.[9] In 1909, after helping draft the legislation creating New Hampshire's State Forestry Department,[19] he became a member of the New Hampshire Forestry Commission;[35][a] and its chair from 1910 until 1952,[37] playing a significant role in shaping the forestry practices and laws of the state.[38] Brown also served on the boards of several industry groups, including the American Forestry Association, Society of American Foresters, Canadian Pulp and Paper Association, and the Forest Research Council.[28][39] He represented the U.S. at the first World Forestry Congress held in Rome in 1926.[9]

During World War I, in his capacity as chair of the New England Forestry Commission, Brown worked with the War Industries Board to send 10 sawmills abroad. The equipment went to Scotland to meet Britain's need for lumber.[40] When the war effort in France subsequently required more than 73 million board feet of lumber per month,[41] Brown was commissioned as a major to oversee sawmill operations there, but ultimately was not allowed to serve in France because of his poor vision,[28] as he was partially blind in one eye.[3]

The Great Depression had a significant impact on the Brown Company. Berlin at that time had a population of about 20,000 people, most of whom either worked for the company or provided services to the families of company employees.[42] The Brown family had borrowed heavily during the 1920s to fund expansion, and, as stated by a company employee, had become "complacent and overly optimistic." The family's nepotism may also have become a disadvantage.[23] Reduced demand for the company's products forced it to take out short-term loans to provide operating capital,[16] and by 1931 the international financial situation led to major losses in the value of the company's bonds.[43][44] As a result, in the winter of 1931–32 the Brown Company could not obtain the necessary financing for its logging operations, when it normally needed to employ 4,000 to 5,000 loggers to cut timber each winter.[43] Family members sold off personal holdings to try to keep the company solvent, and W. R. Brown dispersed his entire herd of Arabian horses.[44] In 1933, he negotiated a cooperative financing plan with the City of Berlin and the State of New Hampshire, ratified by the state legislature, to fund the woods operations, keeping Berlin's local residents employed.[1][22] The company was nevertheless forced to file for bankruptcy in 1935,[16] after having gone into receivership the previous year.[43] A court-appointed president took over, but Brown continued as head of the Woods Division.[44] Brown's agreement with the City of Berlin lasted until 1941, when the company again filed for bankruptcy. Ultimately the Brown family ceased to have a significant role on the board of directors and the company was sold to outside investors.[43][45] Brown officially retired from the company in 1943,[8] but his brother O. B. remained on the board of directors until 1960.[16]

Arabian horse breeder

[edit]

Brown bought his first Arabian horses in 1910 and founded the Maynesboro Stud near Berlin in 1912.[47] The farm was named after the original settlement in the area, Maynesborough, located in the White Mountains in an area also known as the Great North Woods Region. The main stallion barn, although moved from its original location, has been preserved and restored by the Berlin and Coös County Historical Society,[48][49] which is also restoring the work horse barns of the Brown Company.[50] On September 15, 2012, the society celebrated the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Maynesboro Stud.[51]

At its peak, Maynesboro was the largest Arabian stud farm in the United States.[52] In 1919, Brown had 88 horses, some at his main farm in New Hampshire, and others at farms he owned in Decorah, Iowa, and Cody, Wyoming.[53] He is credited as the breeder of 194 horses,[51] and became known as one of the most knowledgeable breeders and authorities on Arabians.[54] He served as President of the Arabian Horse Club of America, now part of the Arabian Horse Association, from 1918 until 1939.[55]

Foundation stock

[edit]As he built Maynesboro, Brown studied the pedigrees of almost every purebred Arabian in the US at the time. He believed the Arabian was actually a separate subspecies of horse,[55][56] a once-popular but now discredited theory.[57] He found that, even though developed in the desert, Arabians adapted well to the severe winter weather of his New England farm.[46]

When he started Maynesboro, Brown obtained his original foundation bloodstock from his oldest brother, Herbert, who had purchased *Abu Zeyd,[b] a stallion bred by the Crabbet Arabian Stud in England. *Abu Zeyd was considered the best son of his famous sire, Mesaoud.[59] Herbert Brown obtained the stallion from the estate of Homer Davenport following Davenport's death in 1912. The Maynesboro stud also acquired 10 mares from the Davenport estate.[60] Brown considered *Abu Zeyd an ideal representative of the Arabian breed, and when the stallion died, Brown donated the skeleton to the American Museum of Natural History.[55] His other American purchases included most of the horses owned by Spencer Borden's Interlachen Farms in Massachusetts, following Borden's decision to disperse his herd. These horses included animals descended from the breeding program of Randolph Huntington, one of the first people in the United States to breed purebred Arabians.[61][62] Brown also obtained Borden's extensive collection of literary works on horsemanship, Arab culture, and the Arabian horse, which included 8th-century Furusiyya manuscripts.[55] Following this start, he looked abroad for additional bloodstock, eventually importing 33 horses into the United States.[51]

International purchases

[edit]

Many American breeders had purchased horses from the Crabbet Stud, which at the time Brown founded Maynesboro was owned by Lady Anne Blunt and Wilfrid Scawen Blunt.[59] American breeders obtained some of Crabbet's best Arabians during the early 1900s owing to the turmoil within the Blunt family. The couple separated in 1906, and following Lady Anne's death in 1917, Blunt's daughter Judith, Lady Wentworth, became involved in a rancorous and expensive estate battle with Wilfrid over the Crabbet lands and horses.[63] Wilfrid, needing to appease creditors, sold many of the stud's best horses to international buyers for low prices. Through an agent, Brown purchased 20 Crabbet horses in 1918, although for reasons unknown, only 17 actually made it to Maynesboro; he paid only £2727 for the entire lot.[64][c] The most significant animal purchased was the well-known stallion *Berk, who died in America after siring only four foals, much to the dismay of Lady Wentworth, who was trying to buy back the best breeding stock lost to Crabbet because of her father's actions.[66] Brown bought two additional Crabbet-bred horses from England in 1923, although not directly from Lady Wentworth.[53][d]

One of the most notable Crabbet-bred stallions Brown eventually kept at Maynesboro was *Astraled, who had come to America in 1909. This horse had been sold by Wilfrid Blunt to an American buyer from Massachusetts, but after siring only two purebred foals in New England, was sold to the remount, shipped west, and lived in obscurity in Oregon, where he sired no purebred Arabian offspring. *Astraled was ultimately obtained by Brown in 1923, who shipped the aged horse by rail from Idaho to New Hampshire. *Astraled only sired one foal crop at Maynesboro, but that group of foals included his most notable American-bred son, Gulastra.[68]

Brown traveled to Europe with the U.S. Army Remount Service in 1921, visiting a number of major European studs in Austria, France, and Hungary. He met Lady Wentworth at Crabbet on the way home, but did not purchase any of her horses.[67] He imported several Arabian mares from France in 1921 and 1922,[66] in part owing to France's reputation for producing excellent cavalry horses.[69]

In 1929, Brown traveled to Egypt and Syria with Arabian expert Carl Raswan in search of desertbred horses. According to Brown's wife, the two apparently did not get along well, and the five horses purchased during their journey somehow never made it to America. Following that trip, Brown wrote The Horse of the Desert, still considered to be one of the best works written about the Arabian horse.[67]

In 1932, Brown sent his stud manager Jack Humphrey to Egypt, where acting for Brown he bought two stallions and four mares from Prince Mohammed Ali.[70] The Prince was known as a horseman and scholar, publishing a two-volume treatise on the breeding of Arabian horses. Two of the mares purchased were daughters of Mahroussa, whom Brown described as "the most beautiful mare he ever saw".[71] The stallions were *Nasr, a successful race horse, and *Zarife.[72]

Endurance testing and remounts

[edit]

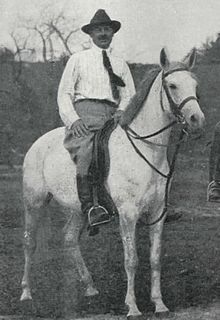

Brown was a remount agent,[68] who served on the U.S. Remount Board,[28] and his interest in improving the quality of horses used by the U.S. Cavalry may have been his motivation to breed Arabians.[67] Spencer Borden shared Brown's interest in Arabians as remount bloodstock.[47] Seeking to prove the superior endurance and durability of Arabian horses to the U.S. Army Remount Service, Brown actively encouraged the participation of Arabians in endurance races.[73][74] He had most of his horses trained to ride and drive. Many were used in endurance races, others shown, and at least one was a polo pony.[75]

In 1918, Brown set up a test ride in which he had two of his horses travel from Berlin to Bethel, Maine, a distance of 162 miles (261 km). They completed the ride in just over 31 hours including breaks; each horse carried a rider and equipment weighing 200 pounds (91 kg) in poor weather and on muddy roads. The horses were Kheyra, a purebred seven-year-old mare who weighed 900 pounds (410 kg), and Rustem Bey, a half-Arab by Khaled out of a Standardbred mare of the Clay Trotting Horses line. Rustem Bey was taller and heavier than Kheyra. Both horses were examined by a veterinarian, assessed as being sound and fit to continue at the end of the ride, and showed no evidence of soreness 24 hours later. A third Arabian, Herbert Brown's *Crabbet, was ridden by a military officer supervising the test, and that pair covered 95 miles (153 km) in seventeen hours. The results of the test were reported in The New York Times.[76]

Following the 1918 test, Brown helped organize the first U.S. Official Cavalry Endurance Ride in 1919, which was won by his mare Ramla, who carried 200 pounds (91 kg).[77] The race covered 306 miles (492 km) in five days.[8] The U.S. Remount Service requested the weight horses carried in 1920 be raised to 245 pounds (111 kg), and required horses to travel for about 60 miles (97 km) a day for five days. Arabians won the highest average points of any breed, and although an Arabian horse did not win first place that year,[77] Rustem Bey was second.[78] In 1921, with a weight requirement of 225 pounds (102 kg),[77] again covering 300 miles (480 km) in five days, Brown's gelding *Crabbet won the race and Rustem Bey placed third,[78] despite a donation of $50,000 from The Jockey Club to the Army to buy the best Thoroughbreds possible in a failed attempt to beat the Arabians. Brown won again in 1923 with an Anglo-Arabian named Gouya, thus retiring the U.S. Mounted Service Cup.[77]

Brown used Arabian stallions owned by the remount service as breeding animals,[68] and over time he also provided 32 of his own stallions to sire remounts. He advocated crossbreeding Arabians to improve other breeds. He concluded, however, that attempting to breed purebred Arabians for increased size resulted in a sacrifice in quality and Arabian type.[55]

Dispersal

[edit]Brown sold all his horses in 1933[79] in an attempt to raise funds to keep the Brown Company solvent.[80] They were bought by the Kellogg Ranch, Roger Selby, William Randolph Hearst's San Simeon Stud,[79] and "General" J. M. Dickinson of Traveler's Rest Stud, who acquired most of the horses from Brown's 1932 importation from Egypt.[53] Dickinson in turn sold *Zarife to Wayne Van Vleet of Colorado in 1939,[72] and Azkar, the last foal bred by Brown,[8] to a ranch in Texas. There Azkar was left to fend for himself on the open range as a herd stallion, but, a testament to the hardiness of Brown's Arabians, he survived and was returned to the Arabian breeding world by Henry Babson. Dickinson sold the mare *Aziza to Alice Payne, who later owned *Raffles.[81]

Legacy

[edit]

Brown believed it was important to preserve the scenic value of New Hampshire's forests.[25] Between 1903 and 1911, he helped with efforts to establish White Mountain National Forest.[19] Among his many civic activities, Brown promoted early legislative efforts to protect public riding trails.[55] He also helped New Hampshire acquire Franconia Notch and Crawford Notch as public lands,[9] and established a river conservation group in Quebec.[34]

A scholar of the Arabian horse, he collected a significant library of works on the breed, one of the largest collections in the United States. His papers are now kept by the Arabian Horse Owners Foundation (AHOF).[67] Today, the term "CMK", meaning "Crabbet/Maynesboro/Kellogg", is a label for specific lines of "Domestic" or "American-bred" Arabian horses. It describes the descendants of horses imported to America from the desert or from Crabbet Park Stud in the late 1800s and early 1900s and then bred on in the US by the Hamidie Society, Huntington, Borden, Davenport, Brown, W. K. Kellogg, Hearst, or Dickinson.[79]

Bibliography

[edit]Brown authored the following works:

- — (1929). The Horse of the Desert (1st ed.). Derrydale Press. OCLC 2438208. Republished in 1947, considered an authoritative work on the Arabian horse.[7]

- — (1958). Our Forest Heritage: A History of Forestry and Recreation in New Hampshire. Derrydale Press. OCLC 2197078. Published posthumously.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Now the State Forest Management Program of the New Hampshire Division of Forests and Lands, New Hampshire Department of Resources and Economic Development[36]

- ^ An asterisk before the name of an Arabian horse indicates that the horse was imported to the United States.[58]

- ^ This was $13,000.00 in 1918 dollars.[65] This amount is equivalent to about £138,000 as of 2011,[65] comparing the historic opportunity cost of £2727 in 1918 with 2011, using the GDP deflator.

- ^ Brown had begun corresponding with Lady Anne in 1916, and respected her love and knowledge of the Arabian horse, describing her favorably as "a true scientist". In 1921, Brown established correspondence with Lady Wentworth, and the two exchanged more than 35 letters over the course of several years. But he did not like her as well as he liked Lady Anne, finding it difficult to get Lady Wentworth to provide a straightforward assessment of her stock. He was frustrated by her excessively favorable descriptions of her horses combined with her harsh criticism of everyone else's. He believed she was simply trying to sell him as many horses as possible and that her prices were too high.[67]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Churchill 1955, p. 3.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011a, 0:04:52.

- ^ a b Steen 2012, p. 44.

- ^ Gove 1986, p. 85.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011a, 0:04:55.

- ^ a b "Hildreth Brown". The Petersborough Transcript. August 2, 1984. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c Churchill 1955, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Steen 2012, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e f "William R. Brown, 80, fire tower pioneer, Williams man, dies" (PDF). The North Adams, Massachusetts, Transcript. August 5, 1955. p. 11.

- ^ Brown, Fielding. "About the artist". Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ Townes, Frances (2007). Misadventures of a Scientist's Wife. Regent Press. OCLC 156822471.

- ^ "Certificates issued". Portsmouth Herald. December 11, 1924. p. 9.

- ^ a b Defebaugh, James Elliott (1907). History of the Lumber Industry of America. Vol. 2. American Lumbermen. p. 70.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011a, 7:08.

- ^ Gove 1986, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d e f Rule, John. "The Brown Company: From north country sawmill to world's leading paper producer" (PDF). Beyond Brown Paper. Plymouth State University, New Hampshire Historical Society. Retrieved August 26, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gove 1986, p. 86.

- ^ Gove 1986, pp. 87, 90.

- ^ a b c d e f Gove 1986, p. 87.

- ^ Gove 1986, p. 89.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011a, 0:04:15.

- ^ a b c Rule, Rebecca. "It Felt Like Death". North Country Stories. Monadnock Institute, Franklin Pierce University. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ a b c Gove 1986, p. 90.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011a, 0:07:00.

- ^ a b Upham-Bornstein 2011a, 0:01:06.

- ^ "Protecting the forest". Museum of the White Mountains. Plymouth State University. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011a, 0:07:58.

- ^ a b c d e Churchill 1955, p. 10.

- ^ "The life and times of W.R. Brown". Center for Rural Partnerships. Plymouth State University. 2011. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011b, 0:01:26.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011a, 8:43.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011b, 0:01:42.

- ^ "2011 NHTOA Centennial Celebration". NH Timberland Owner's Association. 2011. Archived from the original on December 11, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Upham-Bornstein 2011b, 0:02:26.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011b, 0:00:05.

- ^ "State Forest Management Program". NH Division of Forests and Lands. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ Brown, William E. Jr (June 1985). "Guide to the William Robinson Brown papers" (pdf). William Robinson Brown Papers. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011b, 0:00:21.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011b, 0:03:30.

- ^ Report of Forestry Commission. New Hampshire Forestry Commission. 1918. pp. 27–31. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ^ Greeley, W.B. (June 1919). "The American Lumberjack in France". American Forestry. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ Rule, Rebecca (June 11, 2012). "A Brief History of the Brown Paper Company". Northern Woodlands. Center for Northern Woodlands Education. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Upham-Bornstein, Linda. "Berlin history". Berlin, New Hampshire. City of Berlin, NH. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c Upham-Bornstein 2011b, 0:04:40.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011b, 0:06:08.

- ^ a b Steen 2012, p. 49.

- ^ a b Edwards 1973, p. 53.

- ^ Steen 2012, p. 45.

- ^ Leclerc, Donald (November 2, 2011). "Brown Company barns restoration project". News Letter Fall 2011. Berlin and Coös County Historical Society. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- ^ "About us". Berlin and Coös County Historical Society. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ^ a b c Leclerc, Donald (November 3, 2012). "Maynesboro Stud memorial ride". News Letter Fall 2012. Berlin and Coös County Historical Society. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ^ Conn 1972, p. 172.

- ^ a b c Conn 1972, p. 194.

- ^ Forbis 1976, p. 199.

- ^ a b c d e f Steen 2012, p. 48.

- ^ "Standard conformation and type" (published online March 23, 2011). The Arabian Stud Book. Arabian Horse Club Registry of America (now Arabian Horse Association). 1918. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Edwards 1973, p. 27.

- ^ Magid, Arlene (2009). "How to Read a Pedigree". arlenemagid.com. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- ^ a b Steen 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Edwards 1973, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Edwards 1973, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Conn 1972, p. 191.

- ^ Wentworth, Judith Anne Dorothea Blunt-Lytton (1979). The Authentic Arabian Horse (3rd ed.). George Allen & Unwin. pp. 76–82. OCLC 59805184.

- ^ Steen 2012, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b Officer, Lawrence H. (2009). "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present". MeasuringWorth. Archived from the original on November 24, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Edwards 1973, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b c d e Steen 2012, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Edwards 1973, p. 51.

- ^ Cadranell, R.J. (Summer 1989). "The double registered Arabians". The CMK Record. VIII (I). Republished by CMK Arabians, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Steen 2012, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Forbis 1976, pp. 198–199.

- ^ a b Edwards 1973, p. 60.

- ^ Steen 2012, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Churchill 1955, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Edwards 1973, pp. 60–61.

- ^ "Arabian horses prove fit. Complete severe endurance test under service conditions" (PDF). New York Times. October 6, 1918. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Arabians in the U.S. Army? You bet!". Arabian Horse History & Heritage. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Edwards 1973, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Kirkman, Mary (2012). "Domestic Arabians". Arabian Horse Bloodlines. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Upham-Bornstein 2011b, 0:04:58.

- ^ Cadranell, R.J. (November–December 1996). "*Aziza & *Roda". Arabian Visions. Republished by CMK Arabians, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

Sources

[edit]- Churchill, P. W. (1955). "W. R. Brown: Modern pioneer" (PDF). The Brown Bulletin. 4 (2): 3, 10–11.

- Conn, George H. (1972) [1957]. The Arabian Horse in America. A. S. Barnes and Company. ISBN 978-0-498-01093-4. LCCN 57-12176. OCLC 2650806.

- Edwards, Gladys Brown (1973). The Arabian: War Horse to Show Horse (Revised Collector's ed.). Rich Publishing. ISBN 978-0-938276-00-5. LCCN 71-247969. OCLC 1148763.

- Forbis, Judith (1976). The Classic Arabian Horse. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-87140-612-5. OCLC 1945650.

- Gove, William G. (April 1986). "New Hampshire's Brown Company and Its World-Record Sawmill". Journal of Forest History. 30 (2). Forest History Society and American Society for Environmental History: 82–91. doi:10.2307/4004931. JSTOR 4004931. S2CID 131496375.

- Steen, Andrew S. (Summer 2012). "W. R. Brown's Maynesboro Stud" (PDF). Modern Arabian Horse (4). Arabian Horse Association: 44–51. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2012.

- Upham-Bornstein, Linda (2011a). DeGrandprem, Nicole (ed.). The life and times of WR Brown Part 1 (Online video). Plymouth State College: Center for Rural Partnerships.

- Upham-Bornstein, Linda (2011b). DeGrandprem, Nicole (ed.). The life and times of WR Brown Part 2 (Online video). Plymouth State College: Center for Rural Partnerships.