Xanthoria parietina

| Xanthoria parietina | |

|---|---|

| |

| Yellow-orange Xanthoria parietina thallus growing on tree bark, surrounded by Physcia adscendens (greyish), and Trentepohlia algae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Lecanoromycetes |

| Order: | Teloschistales |

| Family: | Teloschistaceae |

| Genus: | Xanthoria |

| Species: | X. parietina

|

| Binomial name | |

| Xanthoria parietina | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

|

List

| |

Xanthoria parietina is a common and widespread lichen-forming fungus in the family Teloschistaceae. Commonly known as the yellow wall lichen, common orange lichen, or maritime sunburst lichen, this leafy lichen is known for its vibrant yellow to orange coloration and environmental adaptability. First described by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, it has become one of the most thoroughly studied lichens, contributing significantly to scientific understanding of lichen biology. Unlike many lichens that are sensitive to pollution, X. parietina grows in diverse habitats—including coastal rocks, urban walls, and tree bark—even in areas with high levels of air pollution and excess nitrogen. Its structure consists of small, overlapping lobes that typically measure less than 8 cm (3+1⁄8 in) across, with coloration that varies from bright orange in sun-exposed locations to greenish-yellow in shaded environments.

The lichen represents a symbiotic partnership between a fungus and green algae of the genus Trebouxia. Its distinctive orange-yellow color comes from parietin, an anthraquinone pigment that accumulates in the outer cortex and serves as a natural sunscreen, protecting the algal partner from excessive light and ultraviolet radiation. Unlike many lichens that reproduce through specialized vegetative structures, X. parietina primarily relies on sexual reproduction through cup-shaped fruiting bodies (apothecia), each of which can release up to 50 spores per minute under humid conditions. When fungal spores germinate, they initially form preliminary associations with common free-living algae in their vicinity. Additionally, the fungus can recruit compatible algal cells from neighboring lichen thalli—essentially extracting these partners—to help establish a complete symbiotic relationship.

Native across Europe, parts of Asia, and coastal North Africa, X. parietina has a more limited and primarily coastal distribution in North America and Australia, where genetic evidence suggests human-mediated introduction. In recent decades, it has expanded inland in these regions, particularly in urban environments and areas affected by agricultural runoff, road salt application, and nitrogen deposition. The lichen grows slowly (averaging 2.6 mm (1⁄8 in) per year) but possesses considerable regenerative abilities, with fragments capable of developing into new thalli. It participates in a complex web of ecological interactions, hosting at least 41 species of lichen-dwelling fungi, while certain gastropods and microscopic rotifers contribute to its dispersal by consuming and excreting viable spores.

The species has high diversity even within local populations, with distinct patterns linked to both geographic location and substrate type. This genetic variability, combined with the lichen's flexible associations with different photobiont strains, contributes to its ecological success. X. parietina serves as a bioindicator for monitoring air quality due to its capacity to accumulate environmental contaminants. Historically, it was used in folk medicine to treat jaundice and as a natural dye source for textiles. More recently, it has become a subject of astrobiology research, where it survives Mars-like environments, space vacuum, cosmic radiation, and extreme cold. This resilience has established X. parietina as a model organism in both environmental monitoring and space exploration research.

Systematics

[edit]Historical taxonomy

[edit]The taxonomic history of Xanthoria parietina begins in 1753 with Carl Linnaeus, who first described it as Lichen parietinus in his landmark work Species Plantarum.[3] In his brief diagnosis, Linnaeus characterized it as a foliose lichen with curled yellowish-brown lobes and a matching surface, citing Dillenius's earlier depiction and noting its broad European distribution on walls, rocks, and wood.[4] Linnaeus's original specimens of Lichen parietinus are preserved in the Linnaean Herbarium (LINN), both labeled with his Species Plantarum number 25. These specimens have caused taxonomic confusion, as one actually corresponds to Rusavskia elegans (formerly Xanthoria elegans), while the other has features resembling Xanthoria ectaneoides. A separate specimen in his Flora Suecica collection was later reassigned to X. parietina. Due to these inconsistencies, taxonomists designated the illustration cited by Linnaeus from Dillenius (1742) as the lectotype, with a corresponding specimen in the Oxford herbarium (OXF) designated epitype.[3]

Early lichenologists later reclassified the species in different genera. For instance, Erik Acharius (1803) referred to it as Parmelia parietina in his work Methodus,[5] and Giuseppe De Notaris (1847) listed it as Physcia parietina. Johannes M. Norman (1852) treated it under Teloschistes (a related genus of orange-colored lichens), calling it Teloschistes parietinus.[6]

The modern genus Xanthoria was established by Theodor Fries. In 1860, he formally recombined the species as Xanthoria parietina. In his treatment, Fries recognized a distinct form, which he called Xanthoria aureola, distinguishing it from the more common form of X. parietina. He described aureola as a primary and fundamental form of the species, particularly prevalent in Arctic regions, differing from typical X. parietina in its color, rigid thallus, and preference for exposed habitats. Fries also cited Acharius, who considered aureola an intermediate between Xanthoria elegans (now Rusavskia elegans) and X. parietina.[7] These distinctions may have contributed to later taxonomic interpretations that recognized Xanthoria aureola as a separate species.

Xanthoria parietina is the type species of the genus Xanthoria. The designated lectotype for Xanthoria parietina is the illustration cited by Linnaeus from Dillenius (1742).[3] Due to its reclassification across different genera, Xanthoria parietina has accumulated many synonyms in the literature. In addition to generic transfers, various infraspecific taxa (forms, varieties, or subspecies) have been described, particularly regarding morphological variants. The name Xanthoria parietina var. ectanea, originally described by Erik Acharius in 1810,[8] has a long and varied history, appearing under multiple combinations within Parmelia, Physcia, Teloschistes, and Xanthoria, before being recognized at different ranks as a variety, form, or subspecies.[2] Another variation, Xanthoria parietina var. convexa, was described by Veli Räsänen in 1944,[9] though its taxonomic significance has been less widely recognized.[2]

Taxonomists now recognize several taxa, once classified as infraspecific variants of Xanthoria parietina, as distinct species:

- f. antarctica (Vain.) Hue (1915) is now Polycauliona antarctica[10]

- f. ectaneoides (Nyl.) Boistel (1903) is now Xanthoria ectaneoides[11]

- f. ectaniza Boistel (1903) is now Rusavskia ectaniza[12]

- f. polycarpa (Hoffm.) Arnold (1881) is now Polycauliona polycarpa[13]

- subsp. calcicola (Oxner) Clauzade & Cl.Roux (1985) is now Xanthoria calcicola[14]

- subsp. phlogina (Ach.) Sandst. (1912) is now Scythioria phlogina[15]

- var. aureola (Ach.) Th.Fr. (1860) is now Xanthoria aureola[16]

- var. australis Zahlbr. (1917) is now Jackelixia australis[17]

- var. contortuplicata (Ach.) H.Olivier (1894) is now Xanthaptychia contortuplicata[18]

- var. incavata (Stirt.) Js. Murray (1960) is now Dufourea incavata[19]

- var. lobulata (Flörke) Rabenh. (1870) is now Seawardiella lobulata[20]

- var. mandschurica Zahlbr. (1931) is now Zeroviella mandschurica[21]

- var. rutilans (Ach.) Maheu & A.Gillet (1924) is now Xanthoria rutilans[22]

Xanthoria coomae, described from New South Wales in 2007,[23] and Xanthoria polessica, described from Belarus in 2013,[24] were later evaluated to be synonyms of Xanthoria parietina.[1]

Phylogenetic relationships and molecular studies

[edit]Modern taxonomy places X. parietina in the family Teloschistaceae, order Teloschistales, within the class Lecanoromycetes (lichenized Ascomycota).[25] It is closely related to other orange lichens such as those in the genera Caloplaca, Teloschistes, and other members of the Xanthorioid clade of the Teloschistaceae. Molecular studies have helped clarify its phylogenetic relationships. For example, DNA sequence analyses provided evidence that X. parietina is genetically distinct from Xanthoria aureola, another yellow coastal lichen that had sometimes been considered merely a variety or form of X. parietina. Their study confirmed that X. aureola is a separate species, not conspecific with X. parietina.[26]

Microscopic studies have established Xanthoria parietina as the prototype species for the "Teloschistes-type" ascus, a structural category characterized by an apically thickened, strongly amyloid outer layer and a dome-like apex that splits longitudinally during spore release. This ascus type, originally described in members of Xanthoria, Teloschistes, and related genera, differs from the "Lecanora-type" by lacking a specialized discharge mechanism and instead relying on simple rupture for ascospore release. Early electron microscopy investigations of X. parietina helped clarify the functional nature of this ascus and its distinction from other ascus types found in lichenized fungi.[27]

Naming

[edit]The etymology of the current name is rooted in its appearance and habitat. Xanthoria derives from the Greek xănthós, meaning 'yellow', with the generic suffix oria ("pertaining to"), and alludes to the lichen's bright orange-yellow color.[28] The species epithet parietina comes from Latin parietina ('of walls'), referring to its frequent occurrence on walls. Thus, the name Xanthoria parietina essentially means "yellow wall (lichen)", a fitting description of this common orange lichen, and one of its several English common names.[29] Other common names used for this species include "common orange lichen", "yellow scales",[30] "maritime sunburst lichen", "wall lichen",[31] and "shore lichen".[32][33]

Description

[edit]

The vegetative body of the lichen, the thallus, is foliose (leafy) and typically less than 8 centimetres (3.1 in) wide. The lobes of the thallus are 1–4 mm (rarely up to 7 mm) in diameter, and flattened,[34] though in African populations the lobes tend to be smaller than those in temperate areas, typically 0.5–2.0 mm wide.[35] The upper surface is some shade of yellow, orange, or greenish yellow, becoming almost green when growing in shaded situations. The lower surface is white, has a cortex, and sparse pale rhizines or hapters that help attach the thallus to its substrate. The vegetative reproductive structures soredia and isidia are absent in this species.[34] X. parietina reproduces primarily through sexual reproduction via apothecia (fruiting bodies). Apothecia typically develop about 2–4 mm behind the growing edge of the thallus and take 12–18 months to reach maturity. Mature apothecia typically measure between 1.5 and 2.6 mm in diameter, though in rare cases they can reach up to 4.3 mm. They can comprise between 0–87% of a thallus's dry weight, with most thalli dedicating 10–30% of their biomass to these reproductive structures. The apothecia can release spores at rates of up to 50 per minute under humid conditions. The production of apothecia appears to be independent of the thallus's directional aspect (north, south, east, or west facing), meaning that sunlight exposure does not significantly influence reproductive effort.[36]

The outer "skin" of the lichen, the cortex, is composed of closely packed fungal hyphae and serves to protect the thallus from water loss due to evaporation as well as harmful effects of high levels of irradiation. In X. parietina, the thickness of the thalli is known to vary depending on the habitat in which it grows. Thalli are much thinner in shady locations than in those exposed to full sunshine; this has the effect of protecting the algae that cannot tolerate high light intensities.[37]

The ascospores made by X. parietina are hyaline (colorless and translucent), ellipsoid, and typically measure 13–16 by 7–9 μm. Like all Teloschistaceae lichens, they are polarilocular, meaning they are divided into two components (locules) separated by a central septum with a perforation. This septum ranges from 3 to 8 μm wide.[38]

| Microscopic characteristics of Xanthoria parietina: (Single apothecium) Mature apothecium showing the orange-yellow disc surrounded by a thalline margin; (Sectioned apothecium) Cross-section of an apothecium revealing the orange-yellow hymenium, green algal cells in the margin, and hyaline supporting fungal tissue; (Illustration) Vertical section of apothecium depicting paraphyses (a), asci with polarilocular spores (b), and hypothecium (c); (Ascospore) High-magnification view of a polarilocular ascospore (scale bar: 1 μm) with its characteristic central septum and perforation, typical of the family Teloschistaceae. |

Similar species

[edit]Xanthoria parietina can be confused with several closely related species, particularly X. aureola and X. calcicola. Molecular evidence supports that these are distinct species, though they share morphological similarities. X. aureola was historically considered synonymous with X. parietina but is now recognized as a separate species. Compared to X. parietina, X. aureola has a thicker thallus (averaging 320 μm vs. 236 μm), narrower lobes at their widest point (averaging 2.3 mm vs. 2.9 mm), and a rough upper surface with visible crystals rather than smooth. The central parts of X. aureola are covered with overlapping, crenulate to strap-shaped lobules. It typically produces fewer apothecia, and shows an ecological preference for seashore rocks, while X. parietina occurs on various substrates.[39]

Xanthoria calcicola differs from X. parietina by its rough upper surface with crystals, central parts covered with coarse isidia or papilla-like projections, and dull orange-yellow color compared to the brighter yellow of X. parietina. It typically has scattered apothecia when present (versus abundant in X. parietina), thalline margins of apothecia that range from smooth to rough to crenulate, a distinct chemosyndrome (a set of related secondary metabolites), and preference for calcareous substrates like stone walls, rarely growing on bark. Molecular analysis shows X. calcicola and X. aureola are more closely related to each other than either is to X. parietina, though they remain genetically distinct species with different morphological features and ecological preferences. The presence of crystals on the upper surface is a key characteristic that distinguishes both X. aureola and X. calcicola from X. parietina, which has a smooth upper surface.[39]

Another possible lookalike, Rusavskia elegans, has smaller convex lobes that measure up to 1.3 mm wide.[38]

Photobiont

[edit]

The photosynthetic partners, or photobionts, of X. parietina belong to the green algal genus Trebouxia, including Trebouxia arboricola and T. irregularis. These algae also exist independently in nature, occurring on both lichen-colonized and lichen-free bark.[40] A study found that the photobiont occupies 7% of the thallus volume in X. parietina.[41] Pigmentation density in the upper cortex varies, regulating light exposure to the algae. The Trebouxia photobiont adjusts its photosynthetic activity seasonally, supporting X. parietina in sunlit environments. As sunlight increases in spring, the photobiont reduces chlorophyll levels and produces protective pigments to dissipate excess light as heat. Chlorophyll concentrations are lowest in spring and peak in winter, balancing light absorption and photoprotection throughout the year.[42]

X. parietina associates with diverse photobionts. It primarily partners with Trebouxia decolorans when growing on bark and with T. arboricola on rock. Even within local populations, genetically distinct photobionts often coexist in adjacent thalli. One study identified 36 algal genotypes among 38 epiphytic samples from a single site. Despite T. decolorans being assumed to reproduce asexually, multiple algal strains sometimes occur within a single thallus, suggesting photobiont switching or thallus fusion. This diversity may contribute to X. parietina's adaptability across varied environments.[43]

Although free-living algae are abundant, X. parietina selectively associates with Trebouxia species. Fungal proteins, including algal-binding proteins, may mediate this selection by recognizing compatible photobionts. These proteins interact specifically with Trebouxia cell walls, suggesting a biochemical mechanism for partner recognition.[44] Bubrick and Galun (1980) identified a protein in X. parietina that binds selectively to the cell walls of its cultured photobiont, with binding strength correlating with acidic polysaccharide levels. This interaction may be crucial during lichen resynthesis, as X. parietina propagates via fungal spores and must recruit new photobionts from the environment.[45]

Live-cell imaging has revealed a dynamic mitochondrial network (chondriome) in Trebouxia freshly isolated from X. parietina.[46] The findings suggest that mitochondria may be shaped by the lichenized state and contribute to energy exchange with the fungal partner. They also appear to play a role in stress responses, such as desiccation tolerance, typically studied in relation to the chloroplast. These insights may help clarify physiological interactions in lichen symbiosis.

Chemistry

[edit]

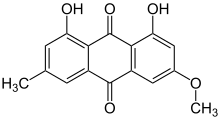

Like many lichens, Xanthoria parietina produces various secondary metabolites (lichen substances), primarily anthraquinone pigments that contribute to its vivid color. Its dominant compound, parietin, is an orange-yellow anthraquinone that accumulates in the outer cortex and is sometimes referred to as physcion in chemical literature.[47] Parietin typically makes up 2.1% of the thallus dry weight and forms a hydrophobic layer in the upper cortex above the algal layer.[48] It is deposited as tiny crystals in the upper cortex, where it protects the photobiont. Parietin synthesis is stimulated by UV-B radiation[47] and photosynthates from the Trebouxia symbiont.[49] In addition to shielding against UV radiation, parietin acts as a barrier against environmental toxins, particularly heavy metals.[48]

Parietin, an anthraquinone pigment, not only gives X. parietina its bright orange color but also protects it from visible light (400–500 nm). Experimental removal of parietin led to increased photoinhibition, especially in hydrated thalli, confirming its protective function. However, when desiccated, X. parietina remained phototolerant, suggesting that structural adaptations also contribute to its light resistance.[50] In addition to its role in photoprotection, parietin enhances desiccation tolerance by stabilizing cell membranes and modifying the upper cortex to improve water retention.[51]

Parietin is highly effective in UV protection, absorbing UV-B radiation with a peak at 288 nm. This trait is particularly beneficial in UV-intense habitats such as coastal cliffs and alpine regions. Experiments confirm that UV-B light is necessary for parietin synthesis—under controlled conditions, thalli exposed only to photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) regenerated 12% of their parietin, while those exposed to UV-B restored 35%.[52] Despite lower UV-B levels in Arctic environments, X. parietina maintains high parietin concentrations, suggesting that additional environmental factors regulate its production.[52] Seasonal field studies show that parietin levels in Xanthoria parietina follow an annual cycle. In naturally occurring populations, concentrations were lowest in winter and nearly doubled by the summer solstice. This pattern mirrors seasonal shifts in UV-B radiation, suggesting that parietin synthesis is rapidly upregulated in spring to shield the photobiont from excess light and declines more gradually in autumn as irradiance decreases.[53]

In addition to parietin, X. parietina produces several related anthraquinones, including fallacinol (also called teloschistin), fallacinal, emodin, and parietinic acid. Fallacinol and fallacinal are minor anthraquinones, while emodin is another orange pigment found in some lichens. These compounds contribute to the chemical profile of X. parietina and have been investigated in phytochemical studies. Recent research (2023) has explored X. parietina as a natural source of anthraquinones for synthesizing pharmaceutical derivatives, such as O-methylated and acylated anthraquinones.[54] X. parietina also produces the secondary metabolite 2-methoxy-4,5,7-trihydroxy-anthraquinone,[55] as well as tocopherol and ergosterol.[56]

Beyond anthraquinones, X. parietina contains additional pigments, including carotenoids such as mutatoxanthin, which contribute to its photoprotective capabilities. The total carotenoid content in X. parietina can reach up to 94.7 mg/g dry weight, significantly higher than in some related species, indicating a strong investment in light protection mechanisms. Furthermore, the synthesis of anthraquinones in X. parietina is linked to its symbiotic relationship with Trebouxia algae—ribitol, a carbohydrate supplied by the photobiont, has been shown to significantly enhance parietin production when provided in culture.[52]

In lichenology, simple chemical spot tests are used to detect certain compounds in situ, and X. parietina yields clear results due to its anthraquinone pigments. A standard test is the K test (using potassium hydroxide solution). On X. parietina, applying KOH to the cortex produces a deep purple reaction (K+ purple). This is a classic indication of anthraquinones like parietin – the KOH causes parietin to form a purple salt (a distinctive color change). Other spot test results for this lichen are negative: C–, KC–, and P–.

In addition to its anthraquinone pigments, Xanthoria parietina contains small amounts of calcium oxalate, a secondary metabolite that occurs in many lichens, particularly those growing on calcareous substrates. However, unlike strictly calcicolous species such as Caloplaca heppiana and Lecanora calcarea, which accumulate large quantities of calcium oxalate, X. parietina was found to contain only minor traces of this compound. This suggests that while X. parietina can tolerate limestone habitats, it does not rely on extensive oxalate production for calcium regulation or substrate modification to the same extent as obligate calcicoles.[57]

Physiological adaptations

[edit]Xanthoria parietina regulates water balance while maintaining gas exchange, allowing it to tolerate fluctuating moisture conditions. This adaptation is largely due to the class I hydrophobin protein XPH1, which self-assembles into a hydrophobic rodlet layer on fungal hyphae in the medullary and algal layers of the thallus.[58] The hydrophobin layer prevents waterlogging while preserving air spaces essential for CO2 and O2 diffusion. Unlike the hydrophilic outer cortex, which absorbs water, the fungal hyphae are coated with a hydrophobic barrier, ensuring continuous gas exchange even in rain or high humidity. This feature is especially beneficial in coastal and riparian environments, where frequent wetting could otherwise disrupt metabolism.[58][59]

The thallus structure of Xanthoria parietina consists of approximately 7% algal cells, 43% fungal tissue, 18% air spaces, and 34% extracellular matrix, which may include glucan or lichenan. The air spaces reduce CO2 diffusion resistance, improving photosynthesis even when fungal walls are water-saturated.[41]

Protein XPH1 forms a stable, insoluble coating that enhances the lichen's resilience. It contains a leucine zipper domain, likely aiding in aggregation at air-water interfaces to prevent liquid infiltration. Freeze-fracture electron microscopy reveals that the hydrophobin layer coats both fungal and algal cell walls, forming a protective boundary between symbiotic partners and the environment.[59] In X. parietina, XPH1 is continuously expressed, unlike in non-lichenized fungi, where hydrophobins appear only at specific stages. Laboratory cultures of the mycobiont grown without its photobiont fail to produce XPH1, indicating that its synthesis depends on symbiosis.[58][59]

The hydrophobin layer also enhances desiccation resistance by repelling excess moisture and preventing prolonged saturation, allowing the lichen to recover quickly from dehydration. This is especially critical in exposed habitats with frequent wet-dry cycles.[58][59] The hydrophobin layer may aid air pollution tolerance, particularly heavy metal resistance, by creating a protective barrier that reduces fungal exposure to toxic particulates. This may explain why X. parietina thrives in urban and industrial environments where other lichens struggle.[58]

Reproduction and dispersal

[edit]

Many lichens disperse via symbiotic vegetative propagules such as soredia, isidia, or blastidia, but X. parietina lacks these structures and must re-establish its symbiotic state with each reproductive cycle. Instead, oribatid mites—Trhypochtonius tectorum and Trichoribates trimaculatus—serve as vectors, consuming X. parietina and dispersing its viable ascospores and photobiont cells through their faecal pellets. This facilitates both short- and long-distance dispersal.[60]

Despite lacking specialized vegetative propagules, X. parietina demonstrates sophisticated reproductive strategies that overcome the challenges of sexual reproduction in lichens. When germinating fungal spores spread across a substrate, they first form associations with common non-symbiotic algae (such as Pleurococcus), creating a preliminary "proto-lichen" stage. This widespread network increases the likelihood of encountering the Trebouxioid photobiont needed for proper thallus development. Additionally, the mycobiont can extract suitable algal partners from the soredia of other lichens, particularly Physcia species that often grow alongside X. parietina and contain compatible photobionts.[61]

Once contact is established with compatible Trebouxia cells, the mycobiont forms specialized structures called haustorial complexes that enable efficient nutrient exchange. These intraparietal haustoria, which penetrate partially into the algal cell wall but not into the cell membrane itself, allow short-distance shifting of photobiont cells and create pathways for carbohydrate translocation from the photosynthetic algae to the fungus. Unlike many other lichens, X. parietina can form several haustoria per algal cell, with each haustorium developed by either a single hypha or multiple fungal hyphae working together, enhancing the efficiency of the symbiotic relationship.[62]

Xanthoria parietina follows a four-stage life cycle with 13 developmental states. After spore germination, growth progresses through protothallus (fungal hyphae only), proterothallus (initial algal association), and juvenile stages, eventually forming a foliose thallus. In young thalli, apothecia cover about half of the thallus margin, but in mature thalli, they occupy only around 1/16 of the margin. This decrease indicates that as the lichen matures, the relative area devoted to reproductive structures declines compared to the overall thallus size. Environmental conditions strongly influence development—thalli in polluted or urban areas often fail to complete their life cycle, whereas those in clean habitats reach full maturity.[63]

Reproductive success varies by substrate—thalli on aspen trees produce more apothecia and spores than those on other species. Additionally, the mycobiont can associate with non-native algae (e.g., Pleurococcus) before establishing its typical Trebouxia or Pseudotrebouxia symbiont, enabling colonization across different substrates.[63]

Xanthoria parietina grows at an average rate of about 2.6 mm per year, though growth varies with habitat. Moist sub-montane environments support faster growth (6–7 mm/year), while drier coastal regions slow expansion. Growth peaks in cold, wet seasons (autumn/winter) and declines in warm, dry conditions, such as Mediterranean climates. The slow growth of X. parietina influences its longevity and dispersal. Without active water uptake, high evaporative demand limits metabolism, especially in wind-exposed, low-altitude regions, where desiccation slows thallus expansion and reduces propagule success. In contrast, high humidity supports steady radial growth, allowing long-term persistence, biomass accumulation, and continuous ascospore release. Strong winds both hinder and aid X. parietina. While wind exposure dehydrates thalli and slows growth, it also disperses thallus fragments, which serve as vegetative propagules in the absence of specialized structures, supplementing spore-based dispersal.[64]

Xanthoria parietina releases and germinates spores year-round, though germination is faster in summer (4–5 days) and slower in winter. Optimal germination occurs at pH 6, but spores tolerate pH 3–7. Germination success and mycobiont development are influenced by multiple environmental factors. Substrate affects success—germination is higher on agar than in water films.[65] In the laboratory, the ascospores of X. parietina germinate best in liquid nutrient media, particularly malt-yeast extract, which provides essential carbohydrates, amino acids, and vitamins. Higher temperatures accelerate germination, with 23 °C (73 °F) promoting faster colony formation than 19 °C (66 °F). Light exposure is unnecessary for early fungal growth—cultures in darkness develop healthier, more extensive mycelial networks.[66]

Developing mycobiont morphology provides insights into early symbiosis. In vitro, X. parietina forms septate, branched hyphae, which later develop into lobed structures, resembling early lichen thalli. Scanning electron microscopy reveals a dense, interwoven hyphal network, potentially facilitating photobiont interactions during natural lichenization. These adaptations support X. parietina's regenerative ability and symbiotic establishment across varied environments.[66]

Although X. parietina lacks specialized vegetative propagules, it has a regenerative capacity that enhances its ecological success. Older, apothecia-covered thalli detach along drought-induced cracks, while younger margins remain attached. When fragments land on suitable substrates, they regenerate new lobes along wound margins, acting as natural propagules. Field studies show a 150% laminal size increase in just 13 months in regenerating thalli. In a five-year experiment, X. parietina maintained 50% substrate coverage, despite losing 90% of its initial thallus area, as regrowth compensated for these losses. Total turnover (growth + loss) exceeded 170%, highlighting its dynamic life cycle.[67]

Regeneration is driven by actively dividing fungal and algal cells within mature thallus areas, allowing new growth from virtually any part of the lichen body, including apothecial disk margins. This adaptation is particularly evident in X. parietina and some Teloschistales species, providing a significant ecological advantage over lichens that lack both vegetative propagules and high regenerative ability.[67] This fragmentation-based dispersal contributes to the species' resilience and widespread distribution.[68]

Habitat and distribution

[edit]Xanthoria parietina is a cosmopolitan species reported from Australia, Africa, Asia, North America, and throughout much of Europe.[69] In eastern North America and Europe, it is more frequently encountered near coastal locations, and in Southern Ontario, Canada, its reappearance has been attributed to increased nitrate deposition associated with industrial and agricultural developments.[70]

The species shows a strong preference for coastal habitats, where it benefits from marine aerosol deposition. In Maine, USA, X. parietina is abundant on gravestones near the ocean but declines sharply further inland. It becomes rare beyond 40 km (25 mi) from the coast in southwestern Maine and 130 km (81 mi) inland in eastern Maine. This inland distribution pattern is largely influenced by the deposition of marine-derived nutrients, particularly chloride and sodium, which are transported inland by wind and precipitation.[71]

In North America, the species was historically limited primarily to coastal regions—along the Atlantic coast from Newfoundland to Pennsylvania, along the Pacific coast from California to the Pacific Northwest, and in a small part of the Gulf coast in Texas. Within the Pacific Northwest, its traditional range was described as west of the Cascades, from the Willamette Valley to the Puget Sound region. Since the early 2000s, however, the species has been documented in several inland cities in Idaho, Washington, and parts of western Montana. These inland occurrences are predominantly associated with urban environments, particularly in arboretums and parks on planted ornamental trees, suggesting human-mediated dispersal.[72] These documented range expansions have identified X. parietina as one of the few lichen species to have become demonstrably invasive in new territories, primarily through horticultural introduction pathways.[29] Research indicates that X. parietina is being transported inland on nursery stock from coastal regions, as evidenced by its presence on commercial nursery plants and absence from naturally occurring woody plants in undisturbed areas outside these cities.[72]

Wind direction plays a critical role in shaping the inland extent of X. parietina. Southwesterly winds in the warmer months carry marine aerosols further inland, while easterly storms contribute additional sea salt deposition through precipitation. The influence of these aerosols is evident in Maine cemeteries: X. parietina is more frequent in open cemeteries exposed to prevailing winds, compared to wooded cemeteries, which block or capture airborne sea salts, and have significantly lower frequencies of the lichen.[71]

In recent decades, inland populations of X. parietina have been discovered in southern Ontario, suggesting an expansion beyond its traditionally coastal range. Once considered extirpated from the region, the species was rediscovered growing on trees in several inland locations. This inland occurrence raises questions about whether the lichen has reestablished after a long absence or has persisted undetected for decades. The expansion may be linked to increasing nitrogen deposition from agricultural runoff and air pollution, which create conditions favorable for nitrophilous lichens like X. parietina. Another possible factor in its inland spread is the widespread use of road salt in Ontario over the past 50–70 years. Since X. parietina thrives in salt-rich coastal environments, roadside salt deposition may have provided an artificial habitat, mimicking the chemical conditions of maritime regions. The lichen is often found near highways and on trees growing along drainage ditches that receive runoff from fertilized fields, further supporting the role of anthropogenic nutrient enrichment in its inland establishment.[70]

The lichen grows on a range of substrates and in diverse habitats. It is found in hardwood forests within broad, low-elevation valleys and occurs sporadically on Populus and other hardwoods in riparian zones of agricultural and populated areas.[34] It preferentially colonizes the upper parts of trunks (about 70% of total tree height), where the bark is younger and more exposed to sunlight.[73] It is also abundant on farm buildings and on rocks immediately above the high water mark in coastal zones, and on rocky seashores it typically forms a distinct band in the supralittoral zone between more halophilic species below and terrestrial species above.[74] Nutrient enrichment by bird droppings enhances the ability of X. parietina to grow on rock.[75] The species demonstrates substrate versatility and has even been recorded overgrowing lead on lead-incised gravestones in England.[76]

The species demonstrates ecological resilience through its regenerative capacity. Unlike many foliose lichens that show strict positional control of growth limited to thallus margins, X. parietina can initiate new growth from virtually any damaged portion of its thallus. This ability to recover from physical damage or fragmentation allows it to persist in disturbed habitats where other lichens might fail to reestablish.[68]

Additional records indicate that distinct morphological forms occur in anthropogenic habitats. A granulose form (formerly known as Xanthoria aureola) has been recorded predominantly on roofs in southeastern England.[77]

Ecology

[edit]Xanthoria parietina demonstrates a range of physiological and morphological adaptations that facilitate its survival in diverse habitats. Populations in drier, more exposed habitats produce longer-chain surface hydrocarbons (alkanes), whereas those in more humid, cooler regions synthesize shorter-chain alkanes—a response that helps reduce water loss, similar to adaptations seen in vascular plants.[78] Its thallus morphology is plastic; forms in moist stream beds tend to be semi-erect and orange-yellow, whereas those in drier, sun-exposed sites are more compact and darker orange. These differences appear to be induced by environment conditions rather than genetic differences.[79]

The lichen's survival is closely linked to its dependence on atmospheric humidity. Lacking specialized water-absorbing structures such as roots or stomata, X. parietina absorbs ambient moisture for metabolic activity. When humidity drops, the lichen enters a dormant state, suspending photosynthesis until moisture returns. This poikilohydric strategy enables it to withstand prolonged dry periods, although growth and reproduction are largely confined to humid conditions. In wetter climates, continuous hydration supports ongoing metabolism and faster thallus expansion.[64] Environmental factors—air temperature, wind, and evaporative demand—influence its physiology: higher temperatures accelerate water loss, and strong, dry winds intensify desiccation, particularly in low-altitude coastal regions; conversely, moderate winds with adequate humidity can enhance gaseous exchange and temporarily boost photosynthetic efficiency. This balance between moisture availability and air movement is a key determinant of lichen growth rates across different habitats.[64]

The thallus of X. parietina progresses through distinct ontogenetic stages that reflect its ecological adaptations. In the juvenile and immature phases, the lichen establishes its foliose form and develops a homeomeric structure with a protective upper crust. As it advances to virginal stages, the characteristic rosette shape forms. During the generative period, apothecia develop gradually, shifting from a scattered central distribution in young thalli to a more concentrated arrangement in both central and peripheral regions in middle-aged specimens; these developmental rates vary with environmental conditions, with optimal formation in well-illuminated habitats with moderate nutrient levels.[63]

Ecological competition further influences population structure and morphology. In regions where several nitrophilous lichen species coexist, X. parietina often forms a codominant relationship in early colonization, but its higher tolerance to pollution and nutrient enrichment may eventually lead to greater dominance in altered habitats. This dynamic is reflected in the varying proportions of ontogenetic stages, with balanced age distributions in less disturbed environments and disproportionate representation in stressed ones.[63] On rocky substrates, the lichen colonizes surfaces via hyphae emerging from its lower cortex rather than through rhizines; it can penetrate mineral fissures—especially in calcareous rocks—and on softer substrates like calcarenite, its hyphae may extend 1–2 mm beneath the surface, promoting mineral fragmentation. On harder andesite, the lichen remains largely surface-bound, contributing mainly to mechanical disaggregation rather than chemical weathering.[80]

As a nitrophilous species, X. parietina thrives in nutrient-rich environments. Moderate nutrient input stimulates growth, although excessive levels eventually reduce growth rates. Consequently, it is often abundant in areas affected by agricultural runoff, bird perches, and atmospheric nitrogen deposition,[81] where nutrient enrichment can alter lichen community structures by reducing acid-sensitive species. Bird guano, which is rich in the toxic compound urea, generally excludes most lichens from these habitats; however, X. parietina achieves one of the highest nitrogen contents reported, partly because of its high urease activity that converts urea into CO2 and NH4.[82]

Nitrogen relationships

[edit]Xanthoria parietina is highly adaptable to nitrogen-rich environments, with thalli containing between 11 and 43 milligrams per gram of nitrogen (dry weight), a broader range than most other green algal lichens.[83] The species maintains metabolic balance by shifting resource allocation between its fungal and algal partners, directing more resources to its photobiont under high nitrogen conditions. Unlike nitrogen-sensitive species, X. parietina sustains consistent growth patterns regardless of nitrogen concentration, allowing it to thrive in agricultural areas and urban centers.[84] his adaptation to high nitrogen environments explains its frequent association with eutrophication[85][86] and its common presence near farmland and livestock facilities.[87]

Transplant experiments near a pig farm in Denmark further demonstrated its nitrogen accumulation ability. Lichen thalli exposed to high ammonia levels rapidly increased their nitrogen content, reaching approximately 2.1% within a month, whereas samples positioned 300 meters away maintained lower levels (around 1.6%). In situ samples collected along a transect exhibited a strong linear correlation between thallus nitrogen content and the logarithm of ambient ammonia concentrations.[88] Additional research suggests that X. parietina's nitrogen tolerance may be linked to osmotic adaptations rather than a direct nitrogen preference. It is primarily halotolerant and xerophytic, with cell osmotic values significantly higher than those of non-nitrophytic species. This allows it to take up water from concentrated solutions, including ammonium nitrate deposits, explaining its success in both nitrogen-polluted urban areas and coastal or dry Mediterranean climates where nitrogen levels are low.[89]

Population genetics

[edit]

Genetic studies of Xanthoria parietina have revealed significant differentiation among populations, with genetic variation structured by both geographic distance and substrate type. Populations growing on tree bark show higher genetic diversity than those on rock surfaces, though there is no evidence of restricted gene flow between populations on the same substrate type, even when separated by distances of up to 25 km (16 mi). Despite these genetic differences, no corresponding morphological or chemical variation has been observed.[69]

At fine spatial scales, X. parietina exhibits high genetic diversity within local populations, with most genetic variation (up to 90%) occurring within rather than between populations.[90] Studies using IGS and ITS (genetic markers used to assess variation) reveal significant diversity even among closely located individuals.[91] Research from Storfosna island, Norway, suggests long-term local adaptation to bark or rock habitats has led to habitat-specific genetic variants, shaping the overall population structure.[39]

While local populations may have limited genetic diversity, populations from different geographic regions show significant genetic differentiation. For example, Antarctic populations of Rusavskia elegans from sites just 5–15 km (3.1–9.3 mi) apart differed by one nucleotide. In contrast, those separated by 660 km (410 mi) showed a 14.2% divergence in their DNA sequences. Similar patterns in other Xanthoria species suggest that, despite limited variation within local populations, long-distance dispersal and genetic drift contribute to regional differentiation and ecological adaptation.[92]

At broader spatial scales, X. parietina populations show a pattern of isolation by distance—genetic differences increase with geographic separation.[93] A global genetic study using RAPD-PCR fingerprinting identified just two major genetic clusters worldwide: one in southwestern Europe (Iberian Peninsula, Balearic and Canary Islands) and another spanning Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand. The high similarity between Australian/New Zealand samples and those from Europe indicates the species was introduced by humans to the Southern Hemisphere, possibly via grapevine transport or ship ballast stones.[94] A similar human introduction has been suggested for the lichen in the populated Willamette Valley of the western United States,[34] and in Ontario, where it may have arrived on nursery trees.[38]

The high genetic diversity observed in X. parietina has several practical implications for its ecology and conservation. This diversity likely supports the species' adaptability to different environments—from coastal rocks to urban trees and polluted areas. High genetic variation within local populations provides material for natural selection, enabling adaptation to changing conditions including pollution levels and climate shifts. The different genetic structures between the fungal and algal partners suggest that X. parietina gains ecological advantages by pairing with locally-adapted algal partners, improving its ability to colonize diverse habitats. From a conservation perspective, this genetic diversity helps predict how the species might respond to environmental changes and identifies potentially important population groups for biodiversity management. The genetic structure also reveals patterns of human-assisted spread, as shown by the similarity between European and Southern Hemisphere populations.[93]

Although X. parietina is homothallic (self-fertile), genetic studies reveal it frequently mates with other individuals. This represents a novel reproductive strategy termed 'unisexuality'—a form of homothallism where individuals of a single mating type can still engage in sexual reproduction with others.[95] Genetic analyses of X. parietina and its algal partner Trebouxia decolorans show contrasting population structures. The fungal component displays high genetic mixing and little structure between populations. In contrast, the algal partner shows clear genetic differences between populations, consistent with its primarily asexual reproduction. This suggests that X. parietina's success across diverse habitats may partly come from its ability to associate with different locally adapted photobionts. When compared to fruticose lichens such as Evernia mesomorpha and Ramalina menziesii, X. parietina shows stronger genetic differences among populations within the same landscape. This indicates that X. parietina has more limited genetic exchange between nearby populations than previously thought, possibly due to habitat specialization.[93]

Molecular investigations into the mating-type (MAT) loci have further revealed the reproductive strategies within Xanthoria. While X. parietina is homothallic—possessing only a MAT1-2 gene (although truncated)—species such as X. polycarpa are heterothallic, with distinct MAT idiomorphs (different mating-type genetic regions). These differences in mating system structure can significantly affect population genetics, influencing levels of genetic diversity, gene flow, and ultimately speciation processes within the genus.[96]

Pollution tolerance

[edit]Xanthoria parietina is highly resistant to air pollution, including heavy metals, nitrogen compounds, and ozone. Laboratory experiments have shown that it tolerates exposure to air contaminants and bisulfite ions with little or no damage.[97] It is also resistant to heavy metal contamination[98] and nitrogen pollution.[99] The mechanisms underlying this tolerance involve multiple protective systems. The parietin layer in the upper cortex acts as a hydrophobic barrier, reducing the penetration of toxic metal ions into the photobiont cells. Experimental studies have shown that parietin-deficient thalli experience greater physiological stress when exposed to heavy metals.[48] Parietin also contributes to ozone tolerance; fumigation experiments revealed that samples containing parietin recovered photosynthetic efficiency and chlorophyll integrity more quickly than those without it, suggesting an antioxidant function in addition to its role as a light-screening pigment. Furthermore, reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels induced by ozone exposure were significantly higher in parietin-deficient samples, reinforcing its role in oxidative stress mitigation.[100] The hydration state of X. parietina influences its ozone sensitivity. Dry thalli suffer less damage and recover more quickly than hydrated ones, likely because reduced gas exchange limits ozone penetration. This factor helps explain the lichen's resilience in Mediterranean climates, where it often remains desiccated during periods of high ozone pollution.[100]

Both symbiotic partners contribute to detoxification within the thallus. The photobiont is particularly vulnerable to metal toxicity due to its delicate photosynthetic machinery but mitigates damage through the synthesis of phytochelatins—sulfur-rich peptides derived from glutathione that bind and sequester metal ions. These compounds serve as a secondary defense when metals penetrate the parietin barrier. The mycobiont also aids metal tolerance through cell wall immobilization of metals and the production of antioxidant compounds.[48] Other protective mechanisms include pH buffering, high potassium content, and antioxidant properties of parietin. The lichen also mounts induced detoxification responses, including conversion of toxic sulfur dioxide to non-toxic sulfate, increased glutathione production, enhanced synthesis of proline and arginine, and improved ROS detoxification.[97] These adaptations help maintain stable physiological functions in polluted environments: its chlorophyll remains intact, photosynthetic activity declines only moderately, cell membranes maintain integrity with minimal electrolyte leakage, and ATP levels remain constant.[101] These characteristics allow X. parietina to persist in polluted environments where many other lichen species decline.

Response to pollution and environmental stress

[edit]Historical records indicate that X. parietina persisted in London despite severe air pollution, even when many other lichens disappeared. Mid-20th century mapping studies revealed that its distribution correlated with areas of moderate sulphur dioxide concentrations, but it was absent from the most polluted zones of central London, suggesting that while resistant to airborne contaminants, it has an upper tolerance limit.[102] However, it is sensitive to certain pollutants, as demonstrated after the Torrey Canyon oil spill, when oil contamination and toxic dispersants caused widespread mortality on coastal rocks. Affected thalli lost their characteristic orange pigmentation, indicating chemical damage that interfered with enzymatic and protein activity, ultimately leading to detachment from the rock surface.[103] The dispersant BP 1002, used during cleanup efforts, was later found to be highly toxic to marine life and coastal lichens. In X. parietina, its surfactant components disrupted algal cell membranes, reducing photosynthetic activity and accelerating thallus deterioration.[104]

Pollution affects both the population structure and development of X. parietina. There has been a decline in population density with increasing pollution levels; one study documented approximately 47 thalli per tree in lightly polluted zones, compared to 12 in moderately polluted areas and 9 in severely polluted regions.[63] In unpolluted environments, the lichen completes its full life cycle, reaching maturity and old age. However, in polluted urban areas, lichen bodies often die before reaching these later developmental stages. Morphological effects of pollution include smaller thalli, fewer and smaller apothecia, and weaker substrate attachment at later developmental stages.[63] Rather than accelerating development under stress, as some plant species do, X. parietina exhibits retarded development of pregenerative individuals and elimination of less tolerant generative individuals. Its pollution tolerance also varies with light availability; optimal conditions appear to be in areas with low pollution and good illumination, where young generative individuals dominate and reproductive capacity is highest.[63]

The species also demonstrates high metal tolerance. A key mechanism is the immobilization of toxic metals in the apoplast (the extracellular space between the cell wall and plasma membrane), preventing them from entering living cells.[105] Additionally, it produces protective thiol peptides, increases antioxidant production, and maintains membrane integrity under metal stress. Laboratory studies indicate differential sensitivity to various metals, with its tolerance being higher for cadmium and nickel but lower for copper and mercury.[105] It also shows resilience to pesticide exposure, persisting in untreated gardens but declining in semi-intensive orchards and disappearing in intensively sprayed orchards.[106] These physiological responses to various pollutants make this species valuable for environmental monitoring applications.[107][108]

Species interactions

[edit]Lichenicolous fungi

[edit]

Xanthoria parietina hosts a diverse array of lichenicolous fungi—fungi that live on lichens. As of 2017, at least 41 species of lichenicolous fungi have been reported on X. parietina, including both obligate parasites and facultative colonizers. Examples include Athelia arachnoidea, Catillaria nigroclavata, and Capronia suijae. While some of these fungi may be pathogenic, others colonize the lichen without causing obvious damage to the thallus.[109]

In some cases, multiple lichenicolous and saprotrophic fungi can form complex communities on decaying thalli of X. parietina. One study in Austria documented ten different fungal species simultaneously colonizing damaged lichen thalli. The most visually apparent was Xanthoriicola physciae, while the dematiaceous hyphomycete Cladosporium macrocarpum was the most abundant colonizer, covering large areas of the thallus and apothecia with dark cottony filaments. This fungus causes visible discoloration and unevenness of the apothecial discs before eventually destroying the lichen structure. Other notable parasites included Lichenoconium xanthoriae, Lichenodiplis poeltii, and Pyrenochaeta xanthoriae. The highly destructive Marchandiomyces aurantiacus forms distinctive pale orange crumbles on the lichen surface, ultimately shrinking the thallus to a bleached, fragile film that clings to the substrate before complete decay.[110]

Among these, the recently described (2023) fungus Tremella parietinae is found exclusively on X. parietina, where it induces the formation of convex, orange to yellow galls within the hymenium of its apothecia. This fungus is known from several European countries—including Austria, Spain, and Sweden—and likely has a broader distribution wherever its host occurs. Another lichenicolous fungus, Tremella occultixanthoriae, parasitizes X. parietina but develops on the lower surface of the thallus and produces four-celled basidia. Both fungi belong to a broader complex of Tremella species that specialize in infecting Teloschistaceae lichens, often with strict host specificity.[111]

Some common saprotrophic fungi not typically associated with lichens have also been found colonizing X. parietina. These include Epicoccum nigrum, appearing as dark purple-brown hemispherical heaps on the surface of apothecial discs, and Periconia digitata, which forms distinctive stalked spherical heads resembling tiny pins on the apothecia and thallus. The environmental conditions that trigger such extensive fungal colonization remain unclear, although factors like prolonged snow cover, high rainfall, or other environmental stressors may initially weaken the lichen, making it susceptible to fungal invasion.[110]

Another lichenicolous fungus is Arthonia parietinaria, which was long misidentified as Arthonia molendoi or A. epiphyscia. This species forms mat black, dull ascomata that are arranged in large groups of up to 20–30 (sometimes 50) on the thallus surface of X. parietina, including its apothecial margins and hymenia. Unlike A. molendoi (which primarily infects Rusavskia elegans), A. parietinaria appears to be restricted to the X. parietina group and is widespread throughout Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa. The fungus acts as a commensal or weakly parasitic species, causing no significant destruction of host tissue outside infection spots, though larger groups of ascomata may cause slight discoloration of the host thallus.[112]

The biochemical impact of the lichenicolous fungus Xanthoriicola physciae on its host has been investigated using Raman spectroscopy. This technique revealed that the fungus destroys key photoprotective pigments—such as parietin and carotenoids—that are vital for shielding the lichen from intense sunlight. Additionally, the detection of scytonemin—a pigment typically produced by cyanobacteria and known for UV protection—in the infected tissues implies secondary colonisation by cyanobacteria.[113]

Gastropod interactions and dispersal

[edit]

Xanthoria parietina serves as both a food source and shelter for certain gastropods. The snail Balea perversa uses the lichen for shelter and nourishment.[114] Similarly, other gastropods, such as Helicigona lapicida, feed on Xanthoria parietina. This grazing may contribute to lichen dispersal: photobiont cells from X. parietina partially survive passage through the snail's digestive tract, retaining some photosynthetic activity even after digestion. Such survival raises the possibility that snail herbivory could facilitate lichen relichenization—either by recombining surviving symbionts from the same thallus or by mixing photobionts and mycobionts from different individuals in fecal deposits.[115] However, digestion significantly reduces photobiont viability, with photobiont fluorescence (a measure of photosynthetic activity) declining by 41–44% after passage through the snail gut. While some cells remain intact, they often suffer morphological damage (including shrunken chloroplasts and enlarged cell wall-to-membrane distances), leaving it unclear whether surviving photobionts can effectively establish new lichens without viable fungal spores or hyphae.[115]

Microfaunal interactions

[edit]The apothecia of Xanthoria parietina also host microscopic animals. Members of the rotifer genus Philodina have been observed feeding on the lichen's ascospores present on apothecial surfaces. Individual rotifers can accumulate several dozen spores, and when ingesting 20 or more spores, about 15% remain viable and capable of germination after excretion. These findings indicate that rotifers may act as dispersal vectors, dislodging and releasing viable spores in new locations.[116]

Competitive and ecological roles

[edit]Beyond these interactions, Xanthoria parietina often overgrows other epilithic lichens without affecting their photobionts. It also supports microbial communities beneath its thallus, likely benefiting from microhabitats created by its attachment structures.[80] In addition, Xanthoria parietina plays a role in biogeochemical cycling by promoting rock weathering through hyphal penetration and adhesion. Its interactions with minerals such as quartz, feldspar, and muscovite contribute to mineral breakdown, particularly in carbonate-rich substrates.[80]

Finally, the lichen competes with other foliose lichens. In experimental settings, it showed competitive equivalence with Parmelia caperata but was overgrown by Parmelia saxatilis under some conditions. In three-species mixtures, however, X. parietina often gained a competitive advantage—possibly due to its tolerance for elevated nitrogen levels. Its ability to thrive in nutrient-rich environments may allow it to outcompete acidophytic species in habitats influenced by agricultural or atmospheric nitrogen inputs.[81]

When competing with other lichens, X. parietina typically forms codominant relationships rather than completely displacing other species, particularly in early colonization stages. Field studies show that when X. parietina thalli border upon other lichens such as Physcia species, neither distinctly overgrows the other, but rather their marginal lobes intermingle.[67] The frequent co-occurrence of X. parietina with grey-colored Physcia species may represent more than simple cohabitation. Research suggests that during reproduction, fungal spores from X. parietina may engage in a form of reproductive parasitism (a type of symbiosis where a microorganism alters the reproduction of a host) by "stealing" algal partners from Physcia lichens, which contain the same algal species. This algal sharing strategy provides a reproductive advantage, as germinating X. parietina fungal spores can bypass the uncertain process of finding compatible free-living algae.[117]

However, the species engages in a long-term ecological succession pattern. Studies tracking lichen communities over five-year periods found that Physcia species (such as P. adscendens and P. caesia) are comparatively short-lived, typically developing and vanishing within about two years, while X. parietina populations persisted throughout. Eventually, in sheltered or humid locations, bryophytes (particularly Orthotrichum species) tend to invade and overgrow lichen-covered surfaces—representing the normal succession pattern in canopy situations. The regenerative capacity of X. parietina allows it to maintain its presence longer than many other lichen species during this successional process, but it is eventually replaced by vigorously growing mosses in most sheltered habitats.[67]

Uses

[edit]Traditional medicine

[edit]Xanthoria parietina has a long history of use in traditional medicine across several cultures. In Andalucia, Spain, this lichen was known as flor de piedra ('stone flower') or rompepiedra ('stone breaker'). Spanish traditional healers employed it for several purposes: treating menstrual complaints when prepared as a decoction in wine, addressing kidney disorders and toothaches when made into water-based decoctions, and serving as a general analgesic. They also incorporated it into cough syrups along with various plant ingredients.[118]

In European traditional medicine during the early modern era, X. parietina was boiled with milk to treat jaundice, often alongside Polycauliona candelaria.[118] This application exemplifies the Doctrine of signatures – a belief system that plants resembling parts of the body could treat ailments of those parts – as the yellow-orange color of the lichen was thought to indicate its efficacy against the yellowing of the skin in jaundice.[119]

In Traditional Chinese medicine, it was known as Chinese: shí huáng yī ('stone yellow clothes') and valued for its antibacterial properties. The widespread medicinal use of lichens, including X. parietina, had been mostly abandoned by 1800, and these applications represent historical folk remedies rather than evidence-based treatments.[118]

Dyeing

[edit]Xanthoria parietina has been used as a natural dye source for centuries. Historical evidence indicates that ancient civilizations recognized this lichen's dyeing properties. In a 1934 publication, Reginald Campbell Thompson analyzed ancient Assyrian texts that mention lichens and dyeing. Thompson noted that the "yellow wall lichen" was "affirmed to give a good yellow or orange colour, if fixed with alum". Thompson's analysis of these ancient tablets suggests that knowledge of using lichens with alum as a mordant existed in ancient Mesopotamia. Alum (a naturally occurring mineral containing aluminium sulfate) was a mordant used with this lichen primarily to fix the dye to fabrics. Thompson notes that "the discovery of alum was one of the most important events in the history of dyeing." X. parietina was valued for its accessibility, growing readily on tree trunks and walls, and its ability to produce consistent yellow to orange hues when properly processed with mordants.[120]

Parietin is responsible for the lichen's dyeing properties, and pure isolated parietin produces the same color characteristics as whole lichen extracts. When processed using different extraction methods and mordants, this lichen yields a diverse range of colors. Extractions in boiling water produce golden-brown, yellow, and caramel hues, whereas 10% ammonia fermentation processes yield purplish-pink, orange, and pink shades.[121] The POD (photo-oxidized) method, which involves exposing the lichen material to sunlight in an alkaline solution over time, can extract blue or purple dyes from X. parietina.[122]

Alum has proven to be particularly effective as a mordant for X. parietina dyes, allowing the natural colors to develop fully while enhancing their permanence. Mordants function by creating a chemical bridge between the natural dye and the fiber, forming strong bonds that ensure the color's resistance to washing and fading.[121]

Modern research has expanded beyond traditional dyeing applications, focusing on parietin. This hydrophobic compound serves as a natural photoprotective agent for the lichen. Recent studies have explored parietin's potential in nanotechnology, particularly in the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antimicrobial properties.[123]

Research

[edit]Historical

[edit]In 1888, the French botanist Gaston Bonnier demonstrated early experimental evidence for lichen symbiosis through his work with X. parietina (then called Parmelia parietina). He reported creating artificial lichen thalli by replacing the organism's natural algal partner (Protococcus viridis) with different algae species, including Protococcus botryoides and the filamentous reddish alga Trentepholia abietina.[124] While his methods foreshadowed modern microbiological techniques and represented a significant step for the time, modern assessments note critical limitations. His algal sources were not truly isolated (coming from other lichen thalli), and his "synthesized lichens" only vaguely resembled natural specimens, showing fungal hyphae surrounding algal cells but lacking true lichen morphology.[29]

In 1967, Richardson conducted early transplant experiments with X. parietina that helped establish methods for studying lichen adaptability. Using a novel technique of attaching lichen thalli to new substrates with resin glue, the study achieved a 96% survival rate in transplanted specimens. When coastal specimens (var. ectanea) were moved to farm roofs in Oxford, they showed significant morphological changes within 18 months, including increased lobe width from 0.8 mm to 2.4 mm. The study also demonstrated that parietin production could adapt to local conditions within six months, with transplanted specimens eventually matching the pigment levels of native populations. This early research helped establish that while some morphological features remain stable regardless of environment, others show significant plasticity in response to new conditions. The transplantation technique proved valuable for studying both taxonomic relationships and ecological adaptations in lichens, helping lay groundwork for future experimental studies.[125]

In 1986, researchers performed the first complete laboratory resynthesis of X. parietina from its separate fungal and algal components. The experiment involved isolating fungal spores and algal cells, growing them separately, and then allowing them to recombine on an agar substrate. After 8–12 months, the symbionts formed new lichen thalli 2–5 mm across, complete with apothecia. While these artificially created lichens showed a similar basic structure to natural specimens, they differed in some aspects, including paler pigmentation and the absence of some characteristic lichen products. This achievement represented a breakthrough in understanding lichen biology, as successful laboratory synthesis of lichens had been a challenge for over a century.[126]

Biomonitoring

[edit]Xanthoria parietina is an effective biomonitor for tracking air pollution trends and heavy metal accumulation over time. A seven-year study in Adriatic Italy measured nine heavy metals (Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb, V, Cu, Zn, Fe, Al) in 51 locations, revealing spatial and temporal pollution patterns. During the study, Cr, Ni, Zn, Fe, and Al levels increased, likely due to industrial and vehicular emissions, while Pb levels declined, reflecting the phase-out of leaded gasoline. The study also identified pollution hotspots, with elevated vanadium levels near oil refineries (a marker of fossil fuel combustion) and higher copper and zinc concentrations in urban areas, likely from traffic and industry. Statistical analyses showed that Al, Fe, Cr, and Ni were linked to industrial emissions and resuspended soil dust, while Cd, Zn, Cu, and V were associated with oil refinery activities and long-range pollutant transport. This ability to differentiate pollution sources makes X. parietina a valuable tool for environmental forensics and pollution source attribution.[107]

In addition to pollution mapping, X. parietina is used in environmental health risk assessments, identifying areas with persistent heavy metal accumulation that may indicate higher human exposure to airborne contaminants. One advantage of lichen biomonitoring is that it provides a cost-effective alternative to air-quality networks, which require specialized equipment and infrastructure. Because lichens accumulate pollutants over time, they allow for high-density spatial sampling, even in areas lacking automated monitoring stations. This makes X. parietina particularly useful for retrospective pollution assessments and long-term environmental monitoring. Findings from the Adriatic Italy study support its role as a reliable tool for tracking pollution trends, identifying pollutant sources, and informing environmental planning and public health strategies.[107]

Environmental influences on growth rate have important implications for biomonitoring studies that use X. parietina to assess air quality. Because the lichen accumulates pollutants over time, differences in growth rates between populations can affect pollutant load measurements. Thalli in humid, cooler environments may accumulate contaminants at a lower rate than those in drier, warmer habitats simply due to differences in growth and dilution effects. Consequently, lichen-based biomonitoring efforts must consider local climatic conditions to ensure accurate comparisons of atmospheric pollution levels across regions.[64]

Astrobiology and space research

[edit]

Xanthoria parietina's extreme resilience has made it a focus of astrobiology and space-exposure research. Lichens are among the most stress-tolerant life forms, and X. parietina, with its strong UV defenses, has been tested for survivability in space and Mars-like conditions. Laboratory experiments simulating outer space conditions (high vacuum, cosmic UV radiation) exposed the lichen to 10–14 days of extreme stress. The lichen survived, remained metabolically active, and resumed growth after treatment, proving its short-term viability in space environments.[128] Laboratory tests have further demonstrated the lichen's extraordinary cold tolerance, with dry samples surviving immersion in liquid nitrogen at temperatures below −182 °C (−295.6 °F).[29]

Building on these findings, X. parietina was tested under simulated Martian conditions in a 2023 study. Samples were exposed for 30 days to low pressure, a CO2-rich atmosphere, extreme temperature shifts, and high UV radiation. The lichen's health was monitored using chlorophyll fluorescence and structural analysis. It survived the full 30 days, retained photosynthetic ability, and maintained structural integrity, though UV-exposed samples showed reduced efficiency and some pigment degradation. Given this resilience, researchers suggested X. parietina as a candidate for long-term space exposure, such as on the International Space Station or satellites.[127]

A 2024 study further examined X. parietina's physiological resilience under simulated Martian conditions. After 30 days, photosynthetic efficiency dropped by 85% in UV-exposed samples and 46% in non-UV-exposed samples. However, within 24 hours of returning to Earth-like conditions, photosynthesis began recovering, demonstrating X. parietina's ability to repair its photosynthetic system after prolonged extreme exposure.[129]

Recovery appears to be linked to antioxidant production. Under Mars-like conditions, oxidative stress increased antioxidant levels, protecting against UV and temperature fluctuations. Over 30 days, antioxidant levels declined as the lichen neutralized reactive oxygen species (ROS), indicating an adaptive response that supports survival in extreme environments.[129]

X. parietina minimizes metabolism under extreme conditions. In the Mars simulation study, photosystem II efficiency declined under UV stress but remained active. UV-shielded samples performed better, suggesting that without radiation exposure, X. parietina could survive Mars-like cold and low pressure. Raman spectroscopy revealed carotenoid and parietin degradation after prolonged UV exposure, but enough pigment remained to protect vital cells, leaving the lichen's structure intact.[127]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Tsurykau, Andrei; Bely, Pavel; Arup, Ulf (2020). "Molecular phylogenetic analyses reveal two new synonyms of Xanthoria parietina". Plant and Fungal Systematics. 65 (2): 620–623. doi:10.35535/pfsyst-2020-0033.

- ^ a b c "GSD Species Synonymy. Current Name: Xanthoria parietina (L.) Th. Fr., Lich. arct. (Uppsala): 67 (1860)". Species Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ a b c Jørgensen, Per M.; James, Peter W.; Jarvis, Charles E. (1994). "Linnaean lichen names and their typification". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 115 (4): 261–405. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1994.tb01784.x.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1753). Species Plantarum (in Latin). Vol. 2. Stockholm: Impensis Laurentii Salvii. p. 1143.

- ^ Acharius, Erik (1803). Methodus qua Omnes Detectos Lichenes Secundum Organa Carpomorpha ad Genera, Species et Varietates Redigere atque Observationibus Illustrare Tentavit Erik Acharius [A method by which Erik Acharius attempted to classify all known lichens according to their fruiting body structures into genera, species, and varieties, and to illustrate them with observations] (in Latin). Stockholm: F.D.D. Ulrich. p. 213.

- ^ Norman, J.M. (1852). "Conatus praemissus redactionis novae generum nonnullorum Lichenum in organis fructificationes vel sporis fundatae" [A preliminary attempt at a new revision of certain genera of lichens based on their fruiting bodies or spores]. Nytt Magazin for Naturvidenskapene (in Latin). 7: 213–252.

- ^ Fries, Th.M. (1860). Lichenes Arctoi Europae Groenlandiaeque hactenus cogniti [The Arctic lichens of Europe and Greenland known thus far] (in Latin). p. 167.

- ^ Acharius, Erik (1810). Lichenographia Universalis [Universal Lichenography] (in Latin). Gottingen: Apud Iust. Frid. Danckwerts. p. 464.

- ^ Räsänen, V. (1944). "Lichenes novi I" [New lichens I]. Annales Botanici Societatis Zoologicae-Botanicae Fennicae "Vanamo" (in Latin). 20 (3): 1–34 [12].

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina f. antarctica (Vain.) Hue, Deux. Expéd. Antarct. Franç., 1908-10, Lichens: 44 (1915)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina f. ectaneoides (Nyl.) Boistel, Nouv. Fl. Lich. (Paris) 2: 71 (1903)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina f. ectaniza Boistel, Nouv. Fl. Lich. (Paris) 2: 71 (1903)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina f. polycarpa (Hoffm.) Arnold, Verh. Kaiserl.-Königl. zool.-bot. Ges. Wien 30: 121 (1881) [1880]". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina subsp. calcicola (Oxner) Clauzade & Cl. Roux, Bull. Soc. bot. Centre-Ouest, Nouv. sér., num. spec. 7: 830 (1985)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina subsp. phlogina (Ach.) Sandst., Abh. naturw. Ver. Bremen 21(1): 223 (1912)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina var. aureola (Ach.) Th. Fr., Lich. arct. (Uppsala): 67 (1860)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina var. australis Zahlbr., K. svenska Vetensk-Akad. Handl., ny följd 57(no. 6): 49 (1917)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina var. contortuplicata (Ach.) H. Olivier, Rev. Bot. 12: 94 (1894)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina var. incavata (Stirt.) Js. Murray, Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 88: 202 (1960)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina var. lobulata (Flörke) Rabenh., Krypt.-Fl. Sachsen, Abth. 2 (Breslau): 282 (1870)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina var. mandschurica Zahlbr., Annls mycol. 29: 85 (1931)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Record Details: Xanthoria parietina var. rutilans (Ach.) Maheu & A. Gillet, Mém. Soc. Sci. Nat. Maroc. 8(2): 281 (1924)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ Kondratyuk, S.Y.; Kärnefelt, I.; Elix, J.A.; Thell, A. (2007). "Contributions to the Teloschistaceae of Australia". Bibliotheca Lichenologica. 96: 157–174.