Zebra murders

Zebra murders | |

|---|---|

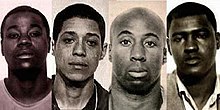

Convicted "Zebra murderers" at the time of their arrest in 1974: Manuel Moore, Larry Green, Jessie Lee Cooks, and J. C. X. Simon | |

| Conviction(s) | First-degree murder and conspiracy to commit first-degree murder |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

| Details | |

| Victims | 15 (confirmed), potentially 73+ dead; 8–10 wounded |

Span of crimes | 1973 (possibly as early as 1970) – 1974 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | California |

| Target(s) | White Americans |

Date apprehended | 1974 |

The "Zebra" murders were a string of racially motivated murders and related attacks committed by a group of four black serial killers in San Francisco, California, United States, from October 1973 to April 1974;[1] they killed at least 15 white people and wounded eight others. Police gave the case the name "Zebra" after the special police radio band they assigned to the investigation.

Some authorities believe that the Death Angels, as the perpetrators called themselves, may have killed as many as 73 or more victims since 1970.[2][1] Criminology professor Anthony Walsh wrote in a 2005 article that the "San Francisco–based Death Angels may have killed more people in the early- to mid-1970s than all the other serial killers operating during that period combined."[3]

In 1974, a worker at the warehouse where the Death Angels were based testified to police for a reward, providing private details about the murders. Based on his evidence, four men were arrested in connection with the case. They were convicted in a jury trial of first-degree murder and conspiracy charges, and sentenced to life imprisonment. The informant received immunity from prosecution for his testimony, and he, along with his family, was admitted to a witness protection program.

The attacks

[edit]1973

[edit]On October 20, 1973, Richard Hague, 30, and his wife, Quita, 28, were abducted at gunpoint and forced into a van while walking from their Telegraph Hill home in San Francisco. Quita Hague's body was found nearly decapitated, over 4 miles away, on a railroad track. Richard Hague, who had been beaten unconscious, was later found wandering near her body with his hands bound and his head and face slashed. He was able to give police a description of the attackers, describing them as three young black men in a white van. The description matched an earlier abduction attempt of three boys, ages 11 to 15.[4]

On October 30, 1973, Frances Rose, 28, was shot repeatedly in her car near the University of California Extension. A witness to the shooting said a man sitting in the passenger seat shot Rose and then jumped out of her car. The man was identified as Jessie Lee Cooks and he was arrested shortly after.[5]

On November 9, 1973, Robert Wayne Stoeckmann, 27, was shot by Leroy Doctor. Just before the shooting, Stoeckmann, a field clerk for Pacific Gas and Electric Company, was on duty, picking up paperwork from various projects, when a well-dressed man asked him for directions to a filling station. The man then pushed Stoeckmann behind a fence and pulled out a .32 caliber revolver, shooting him in the neck. He survived the attack, took the gun away from the man, and shot him three times, in the arm, shoulder, and stomach. Leroy Doctor was arrested and sentenced to a term of 9+1⁄2 years to life in prison.[6]

On November 25, 1973, Saleem Erakat, 53, was found dead in his store, across from the San Francisco Civic Center. Erakat's body was found near an empty cash register, shot in the head, his hands bound with his own necktie. Over $1,000 was stolen from the store. His wallet was found empty on a Muni bus later that day.[7] It was revealed that his murderer was a regular customer who had greeted Erakat in Arabic before this incident. His death was unique as he was an Arab and a person of color killed by the Death Angels.

On December 11, 1973, Paul Dancik, 26, was standing with a friend near a telephone booth. The friend told police that two young black men in navy peacoats approached them and began shooting, killing Dancik. Three .32 caliber shell casings were left at the scene.[8]

Two days later, on the evening of December 13, 1973, Art Agnos, 35, top aide to San Francisco Assemblyman Leo McCarthy, was in Potrero Hill attending a meeting on child-care centers. After the meeting ended, while Agnos was talking with two women outside, a black man walked up and fired two shots into his chest. Agnos survived the attack.[8] Less than 90 minutes later, Marietta DiGirolamo, 31, was standing in a doorway along Divisadero Street when a black man wearing a long leather jacket shot her three times at close range. Police found three .32 caliber shell casings at the place of the shooting.[8][9]

On December 20, 1973, Ilario Bertuccio, 81, was shot four times as he walked across the street while on his way home from his work.[8] Just over two hours after Bertuccio was killed, Terese DeMartini, 20, survived being shot several times near her apartment, while parking her car, after returning home from a Christmas party.[8]

On December 22, 1973, Neal Moynihan, 19, was shot three times while walking near Market Street.[8] Within a few minutes, and a few blocks, of Moynihan's murder, Mildred Hosler, 65, was shot four times at point-blank range.[8]

Initial reports of the Moynihan and Hosler shootings both mentioned a buckskin coat, but witnesses reported different races, and in some instances described a man with a medium complexion. Nevertheless, police indicated that the shootings were likely committed by the same person responsible for five other killings over the previous five days, due to the fact that all seven victims were shot at close range with a handgun, three or four times, and none were robbed.[10]

On December 24, 1973, a dismembered body, named John Doe #169, cut with surgical precision, wrapped in plastic, and stuffed in a cardboard box, was found at Ocean Beach.[11][12] His head, hands, and feet were missing. It was testified that the remaining Death Angels took turns hacking off his limbs, "starting with his fingers, and toes, until he was disassembled like a hog in a butcher's shop" [13]

1974

[edit]The killings resumed on January 28, 1974, with five more shootings; four were fatal. Tana Smith, 32, was shot on the sidewalk, only six blocks from her home. Ten minutes later, and eight blocks away, Vincent Wollin, 69, was shot twice in the back while digging through trash cans for items to repair and sell to supplement his Social Security checks. He died just a few feet from his home, where friends were waiting for him to arrive to celebrate his birthday. John Bambic, 87, a man known for his funny hats, was shot twice in the back, just an hour later, and died immediately. Jane Holly, 45, was doing her laundry when a gunman ran through the door of the laundromat and shot her twice in the back. She died just before she could celebrate her 25th wedding anniversary. Minutes later, Roxanne McMillan, 23, survived being shot twice, as she was removing clothing from her car, by the same man who had just greeted her on the street.[14][15]

On April 1, 1974, Tom Rainwater, 19, and Linda Story, 21, both Salvation Army cadets, were shot while on their way to grab something to eat at a restaurant. Only Story survived the attack.[14]

On April 14, 1974, Terry White, 15, who was waiting for a bus, and Ward Anderson, 18, who was hitchhiking just a few feet away, were each shot twice. Both teenagers survived.[14]

On April 16, 1974, Nelson Shields IV, 23, was making room in a friend's car for a rug he had just purchased when he was shot in the back three times. He died grasping a lacrosse stick.[14]

Operation Zebra

[edit]The murders caused widespread panic in San Francisco. The city suffered losses in revenue by a dramatic drop in tourist traffic; many hotel, nightclub, restaurant, and theater owners reported a decline in business. Streets were deserted at night, even in North Beach, a neighborhood with seven-night-a-week nightlife.[16][17]

A manhunt, dubbed "Operation Zebra" due to the "Z" police frequency used for communication, was launched immediately following the murders on January 28, 1974.[18]

Initial evidence related to the killings revealed a common pattern. In a hit-and-run shooting, the gunman would walk up to his victim, shoot the victim repeatedly at close range, and flee on foot. Another link among the shootings was the killers' preference for a .32 caliber pistol, based on the slugs recovered from the victims and the shell casings found at the crime scenes.[19]

A stop-and-search program was instituted on April 17, 1974, following the shooting of Nelson Shields. The next day, a grid of six police combat zones were set up in the city of San Francisco, and more than 150 officers were deployed into the area. Each officer carried a composite sketch of the suspect, prepared by Homicide Inspector Hobart Nelson, based on the descriptions given by the many witness he interviewed. During the searches, field interrogation cards were filled out when officers deemed further questioning necessary. Recorded on the cards were the individuals' names, ages, addresses, and drivers license and social security numbers. Those cards were turned over to homicide detectives, and ultimately kept on file at the Hall of Justice.[20][21][22][23]

Vocal and widespread criticism from the black community emerged immediately following the start of the program. Black Panther party leader Bobby Seale described the program as "vicious and racist." The general counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union, Paul Halvonik, stated that the measures taken by Mayor Alioto and police "are totally unprecedented in their scope and clearly indefensible in view of the Constitution." The Officers For Justice group, led by Nation of Islam associate Jesse Byrd, described the policy as "racist and unproductive".[24][25]

A week after the program began, Cinque, the black leader of the Symbionese Liberation Army, said, "If we look closely, we begin to see the truth that Operation Zebra is a planned enemy offensive against the enemy to commit a race war," also claiming that it was a means to get "black males to submit to FBI classification and identification."[26]

In response to the public backlash about the program, Alioto compared the interrogations to that of the Zodiac murders, in which hundreds of white people were also stopped, and defended the searches as constitutional.[20] Dr. Washington Garner, the first black Police Commissioner for the city of San Francisco, urged the city's black men, "If you are stopped, don't resent it. Show your identification and, if necessary, permit a search."[27]

Two lawsuits were filed; one by the NAACP, asking that stop-and-search tactic be declared unconstitutional, and another by the ACLU, on behalf of six young black men, asking that the searches be stopped. Nathaniel Colley, an attorney for the NAACP, told the judge, "By admission, the police are engaged in a wholesale violation of every black male's rights if he happens to be what they think fits the description of the Zebra killer."[26][28]

On April 22, 1974, Alioto was spat on and struck on the head with protest signs as he walked through a crowd of about 1,000 demonstrators, organized by a group called, "Coalition to Stop Operation Zebra."[28]

During the hearing for the lawsuits, which began on April 24, 1974, Chief of Inspectors Charles Barca reported that of the 567 black men that had been stopped, 181 field interrogation cards were submitted, and that the searches produced, "no effective leads." A memo from Barca, disclosed that day, revealed directions to police that stated, "be more selective in making stops. Make them when the individual is acting, or appears to be out of the ordinary."[29]

On April 25, 1974, U.S. District Judge Alfonso Zirpoli issued a court order ruling that the searches unconstitutionally violated the rights of young black men, and said officers must have probable cause, and that a likeness to the composite drawing was not enough. Following the order, the police cut back interrogations to just over a dozen per day, and on April 26, 1974, the city filed an appeal to Zirpoli's order.[30][31]

Arrests and convictions

[edit]By April 18, 1974, rewards totaling $30,000 were being offered for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the person(s) involved in the murders.[32]

Arrests

[edit]Just ten days later, on April 28, 1974, Anthony Harris attended a secret meeting with the mayor that led to the arrests of seven men on May 1, 1974, just six months after the killings began. The men were identified as: J. C. Simon, 29; Larry Green, 22; Manuel Moore, 23; Dwight Stallins, 28; Thomas Manney, 31; Edgar Burton, 22; Clarence Jamison, 27; the last four were released due to lack of evidence.[33][34]

It was later reported that Harris, the informant, had actually been in discussions with police prior to meeting with Alioto. In the ten hours of interrogation that was taped, he provided names, vehicle descriptions, stash locations inside of vehicles, and the center location where victims were taken for killing and dismemberment. As a result of this information, a special 28-man group of black police officers was divided into teams in order to maintain 24-hour surveillance on the named suspects. A public reference to this special team was made by Chief Scott on April 23, 1974. As an informant to police, Harris was stashed in a hotel and kept under guard. Two days later, Mayor Alioto was approached by a lawyer on behalf of Harris, who was motivated by a $30,000 reward.[35][36]

Despite this fumble, a meeting attended by the Mayor, Chief Scott, Chief of Inspectors Charles Barca, Lieutenant Charles Ellis, Inspector Gus Coreris, and Prosecutor Walter Giubbini resulted in the decision to move forward with the arrests.

Search warrants were issued for a Black Self-Help center where Green, Simon, and Moore worked, in Green and Simon's apartment, and in automobiles seized. At the center they collected a roll of rope, an axe, bows and arrows, a sickle, a machete, wire, plastic bags, five knives, a small hatchet, a hand saw, and a spear. In the apartment, they found two swords with scabbards and rope.[37]

The statement released by Mayor Alioto,[38] following the arrests, read:

The police have arrested several suspects in connection with the Zebra killings. At this stage of the proceedings all of these suspects are entitled in the presumption that they are innocent. And the police and I are entitled to the opinion that the ring leaders who perpetrated the wave of terror in San Francisco are behind bars. The investigation will continue until we are satisfied that we have rounded up all of the members of this group and have insured the fact that new members will not take their place.

I am confident that the trial judges have ample power to protect the suspects from the publicity which the Zebra slayings have generated. I am also of the opinion that this community is entitled to know the nature of the terrorist organization responsible for the recent rash of crimes.

The San Francisco police, under the leadership of Chief Donald Scott, have pierced the veil of a vicious ring of murders called "DEATH ANGELS." The local group is a division of a larger organization dedicated to the murder and mutilation of Whites and dissident Blacks. The pattern of killing is by random street shooting or hacking to death with machete, cleaver or knife. Decapitation or other forms of mayhem bring special credit from the organization for the killers. Hitchhikers are a particular prey.

"DEATH ANGELS," a kind of reverse Ku Klux Klan, is based on the muddled aberrations clearly outside the mainstream of Islamic religions. In my opinion, it represents as much a potential threat to Blacks as to Whites. Members are usually characterized by trim, neat appearance, and purport to live by a puritanical code of moral conduct. They are fanatical believers in Black separatism. The training of young boys fourteen years of age and over in what they call "martial arts" is a practice of this group. It consists of teaching manual methods and techniques of killing or incapacitating.

Our intelligence indicates that the national leader of this organization is apparently located outside of California and that he determines levels of promotion in the local divisions. The "DEATH ANGELS" who use wings as an insignia, literally earn their promotions upon presentation of proof of the number and nature of the murders committed.

Nearly 80 California murderous assaults, principally in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Alameda, and Sacramento counties between September of 1970 to date, have been characterized by the "DEATH ANGEL" pattern of operations, i.e. unprovoked attacks involving random shooting of Whites in the street or mutilation by heavy-bladed weapons committed by neatly dressed young Black men. An examination of the specific facts in the attached partial list of victims amply supports the inference, on courtroom evidence, that the similarity of pattern is better explained by concert of action than by coincidence.

A concerted drive by local, state, and national law enforcement agencies is desperately needed to shatter this organization. Otherwise the arrest of present perpetrators will result in their replacement by other "DEATH ANGELS." The jails are favorite places of recruitment, with job opportunities upon release as one of the inducements.

Investigation by local police, the FBI, and grand juries, preferably coordinated by the Attorney General of California, is in my opinion an absolute imperative. This investigation must be carried on by skilled, professional, dispassionate police work, avoiding emotional appeals and hysterical speculation. While it must be vigorous and relentless, it must stay within constitutional limitations.

The public is urged to cooperate with police authorities and to come forward with information, with the assurance that all the law permits by way of reward of leniency will be recommended in appropriate cases in exchange for valuable information.

Special care must be taken by public officials and the police to prevent hate groups from converting a criminal investigation into a racial struggle. The inescapable fact of the matter is that most mass murderers of recent years - Manson, the Santa Cruz murderers, Corona, and Zodiac have been White. Murder knows no color and must be fought without aggravating sensitive racial tensions.

For that reason, numerous Blacks and Whites with unquestioned credentials in the Black community must participate in these law enforcement efforts. However, it should be clear that a constitutional assault on a murderous society of brutal killers cannot be diminished because its members are Black, anymore than if they were White. Murder is murder, and no community will endure that approaches the struggle for effective law enforcement with anything less than rugged determination to wipe out organized lawlessness.

Grand jury

[edit]The grand jury's first meeting began on May 6, 1974, with unprecedented security. Witness identities remained protected due to an order banning extrajudicial statements. The following week, protestors from the Progressive Labor Party distributed literature demanding the indictment of Mayor Alioto and the police department for the harassment and terrorization of black people. They also requested the destruction of the Operation Zebra field interrogation cards.[34][22]

A grand jury transcript revealed that police officers unknowingly questioned and released the suspects seven times, including during the abduction on the Hagues. Green, who was driving a white van at the time, was also stopped by an officer on October 31, 1973, but was released. Two months later, on December 22, 1973, Simon and Moore interfered while an officer was conducting a traffic stop. Neither was cited and two hours later two more Zebra murders occurred. Several more times, Simon, Green, and Moore were stopped, and each time they were let go.[39]

On May 9, 1974, Moore, Green, and Simon pleaded innocent to the murder charges. Their bail was set at $250,000 each.[40]

Harris' testimony, which covered 62 pages of the grand jury transcript, indicated he was present for 10 murders but did not actively participate. He said that he was told that the "Death Angels" were "supposed to be a pretty high branch of the Nation of Islam," and had 2,000 members nationwide. He also stated that the killings began after a meeting in September or October in Simon's apartment, at which 12 or 13 people were present. On the date of the Hague murder and assault, Harris testified that Green and Cooks offered him a ride home, but instead made him a participant in the kidnapping of the couple.[41]

On May 16, 1974, the grand jury indicted all four men on murder charges. Moore and Simon were indicted on two counts each of murder and assault with a deadly weapon. Moore was charged with two additional accounts of assault with an additional weapon. Green and Cooks were indicted on one count each of murder, two counts of kidnapping, two counts of robbery, and one of assault with a deadly weapon. Bail was set for each at $300,000.[42]

Trial

[edit]On May 29, 1974, all four suspects pleaded innocent to the charges for the three murders. The trial date was originally set for July 8, 1974, however, due to a scheduling conflict with the defendants' attorney, the trial was postponed multiple times.[43][44][45]

By February 21, 1975, Clinton White, the attorney for defendants Green, Moore, and Simon, said Harris sent him two letters claiming police threatened to revoke his parole if he failed to testify. White, and defense attorney for Cooks, Roger Pierucci, tape recorded an interview with Harris, in which the informant recanted his testimony.[46]

On February 24, 1975, a $14 million lawsuit was filed in which Mayor Alioto and the San Francisco Police Department found themselves the defendants; the Zebra killings defendants and the four men that were released were the plaintiffs. They asked for damages for false arrests and the "fright, shame, humiliation, embarrassment, and worry" suffered.[47]

The trial began on March 3, 1975. During the first day of trial, 48 jurors were excused for hardship. Defense attorney Clinton White requested a delay due illness of their chief strategist, Edward Jacko. That same night, a briefcase, tape recorder, cassettes, and binders concerning the Zebra trial were stolen from the parked car of one of the defense attorneys, John Cruikshank.[48]

After questioning 205 potential jurors over the course of four weeks, on March 27, 1975, the juror panel was seated; five men and seven women.[49]

In opening remarks by the prosecution, District Attorney Robert Podesta stated police have the .32 caliber pistol that was used in 5 of the 20 murders and assaults. He also revealed they have a wedding ring taken from Quita Hague.[50] Harris, who was granted immunity, describing the machete slaying of Quita Hague, said "Larry grabbed the woman by her hair and took a machete knife and took her 20 feet from the van. He raised it over his head and sliced down on her neck. He kept chopping, chopping." He continued, "He came over to where I was standing and said, 'You should have seen the blood gush out of that devil's neck.'" He then described Cooks attack on Quita's husband.[51] Harris also testified that he rode for several hours with the defendants on the night in January that four persons were killed and one was wounded.[52] When questioned about the letters he wrote to defense attorney White, Harris said he "just made up" the story because of pressures on his wife and anger towards the district attorney's office.[53] Michael Armstrong, 23, testified under immunity that he sold the gun that killed and wounded several victims in 1974 to Thomas Manney, manager of the Black Self-Help center and former suspect in the Zebra killings.[54] A month into the trial, a 12-year-old girl identified Cooks in court, as the man who tried to abduct her at gunpoint on October 20, 1973. Her testimony coincided with Harris', who described how he, Cooks, and two other men, attempted to abduct three children before abducting the Hagues.[55] Also heard in the trial was Cooks' confession to the Frances Rose shooting.[56] Linda Story, who survived with a bullet lodged in her spine, testified about the attack on her and fellow cadet Tom Rainwater.[57]

After twelve months, 212 days in court, and testimony from 181 witnesses, jury deliberations began.[58][59] Just three days later, all four defendants were found guilty. Green laughed out loud as jurors were polled; Cooks also laughed after conferring with his attorney. Moore and Simon showed no emotion.[60][61]

Moore and Simon were charged with two counts each of murder and assault with a deadly weapon in the murders of Tana Smith and Jane Holly. Each was also charged with two counts of assault in the attack on Roxanne McMillan. In addition, Moore was charged with assault on Terry White and Ward Anderson. Green and Cooks were charged with one count each of murder, two counts of kidnapping, two counts of robbery, and one assault with a deadly weapon for the murder of Quita Hague and the attack on her husband, Richard Hague.[61]

On March 29, 1976, Cooks, Green, Moore, and Simon were sentenced to life in prison, the maximum penalty allowed.[62]

Aftermath

[edit]On March 12, 2015, J. C. X. Simon (aged 69) was found unresponsive in his cell at San Quentin State Prison, where since 1976 he had been serving a life sentence with the possibility of parole. He was declared dead of unknown causes, pending an autopsy.[63] Moore (aged 75) died in 2017 at the California Health Care Facility.[64] Cooks died in prison on June 30, 2021, at Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility.[65] Larry Green is currently incarcerated in California State Prison, Solano. He was most recently denied parole on July 31, 2024.[66]

Victims

[edit]| Name | Age | Date | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richard Hague | 30 | October 20, 1973 | Survived |

| Quita Hague | 28 | October 20, 1973 | Died |

| Frances Rose | 28 | October 30, 1973 | Died |

| Robert Stoeckmann | 27 | November 9, 1973 | Survived |

| Saleem Erakat | 53 | November 25, 1973 | Died |

| Paul Dancik | 26 | December 11, 1973 | Died |

| Art Agnos | 35 | December 13, 1973 | Survived |

| Ilario Bertuccio | 81 | December 20, 1973 | Died |

| Terese DeMartini | 20 | December 20, 1973 | Survived |

| Neal Moynihan | 19 | December 22, 1973 | Died |

| Mildred Hosler | 65 | December 22, 1973 | Died |

| John Doe #169 | Unknown | December 24, 1973 | Died |

| Tana Smith | 32 | January 28, 1974 | Died |

| Vincent Wollin | 69 | January 28, 1974 | Died |

| John Bambic | 87 | January 28, 1974 | Died |

| Jane Holly | 45 | January 28, 1974 | Died |

| Roxanne McMillan | 23 | January 28, 1974 | Survived |

| Thomas Rainwater | 19 | April 1, 1974 | Died |

| Linda Story | 21 | April 1, 1974 | Survived |

| Terry White | 15 | April 14, 1974 | Survived |

| Ward Anderson | 18 | April 14, 1974 | Survived |

| Nelson Shields IV | 23 | April 16, 1974 | Died |

See also

[edit]General:

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Boca Raton News 1974c.

- ^ Howard 1979, pp. 228, 238–39, 247–48, 266, 333–34.

- ^ Walsh, Anthony (2005). "African Americans and Serial Killing in the Media: The Myth and the Reality." Homicide Studies, Vol. 9 No. 4, November 2005, pp 271-291; doi:10.1177/1088767905280080

- ^ "Slaying link to earlier kidnap try". San Francisco Examiner. October 23, 1973. p. 2. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "SF Woman Found Slain". Napa Valley Register. November 1, 1973. p. 13. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zebra Victim Describes Attack". Santa Cruz Sentinel. May 2, 1974. p. 29. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Robbers execute Civic Center grocer". San Francisco Examiner. November 26, 1973. p. 2. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The 57 Bay Area victims on Alioto's Zebra list". San Francisco Examiner. May 2, 1974. p. 4. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Appeal Courts Reports 1983, p. 268.

- ^ "Man sought in San Francisco killing spree". Independent, Long Beach. December 24, 1973. p. 3. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ocean Beach yields body". Los Angeles Times. December 24, 1973. p. 1. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Howard 1979, pp. 181, 226, 358.

- ^ "Zebra: The True Account of 179 Days of Terror in San Francisco".

- ^ a b c d "List of 18 Victims In Zebra Hits". Vallejo Times Herald. May 2, 1974. p. 4. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Zebra Shootings - Without Warning, Reason, Pity". Los Angeles Times. May 1, 1974. p. 3. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zebra Madness Drives Tourists From SF". The Modesto Bee. April 26, 1974. p. 5. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Howard 1979, pp. 347–48.

- ^ "Operation Zebra: Tense SF Hunts Sect of Killers". The Modesto Bee. January 30, 1974. p. 2. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Howard 1979, p. 235.

- ^ a b "Zebra manhunt engulfs young SF blacks". Independent, Long Beach. April 19, 1974. p. 1. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "All-out hunt for random slayers". San Francisco Examiner. April 18, 1974. p. 1. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Tight Security As Jury Hears Zebra Evidence". Santa Cruz Sentinel. May 14, 1974. p. 12. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "20 attorneys seek Zebra dragnet ban". San Francisco Examiner. April 24, 1974. p. 20. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sanders & Cohen 2006, p. 220.

- ^ "Manhunt for Zebra". Independent, Long Beach. April 19, 1974. p. 8. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "SLA Leader Cinque, Labels Zebra Hunt 'Race War' Effort". The Sacramento Bee. April 25, 1974. p. 2. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Blacks Stopped On SF Streets". Santa Cruz Sentinel. April 18, 1974. p. 1. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Alioto spat upon, hit by protesters of Zebra hunt". Press-Telegram. April 23, 1974. p. 10. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zebra effort ineffective, judge is told". San Francisco Examiner. April 24, 1974. p. 1. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Police deploy against Zebra". Press-Telegram. April 28, 1974. p. 11. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "SF police halt massive questioning". Redlands Daily Facts. April 26, 1974. p. 2. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The City's biggest manhunt - 150 police". San Francisco Examiner. April 18, 1974. p. 22. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "SF Police Arrest 7 Death Angels in Zebra Killings (2)". The Fresno Bee. May 1, 1974. p. 4. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Jurors probing Zebra killings tightly guarded". Independent, Long Beach. May 8, 1974. p. 4. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Real story of Zebra tipster". San Francisco Examiner. May 7, 1974. p. 1. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Nolan's inside on Zebra case". San Francisco Examiner. May 7, 1974. p. 18. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Weapons seized in Zebra probe". The Bakersfield Californian. June 19, 1974. p. 9. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Text of Mayor Alioto's Statement". Vallejo Times Herald. May 2, 1974. p. 4. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "SF Police Stumbled On, Missed Zebra Slaying". The Sacramento Bee. June 13, 1974. p. 14. Retrieved December 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Three Zebra suspects enter innocent pleas". The San Bernardino Sun. May 10, 1974. p. 4. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Death Angels - revenge as motive for murder". Ukiah Daily Journal. June 11, 1974. p. 3. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jury Indicts 4 in SF Zebra Street Killings". The Modesto Bee. May 16, 1974. p. 1. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Innocent Pleas Entered By Zebra Suspects". Santa Cruz Sentinel. May 29, 1974. p. 1. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Trial Date Set for 4 in Zebra Case". Oakland Tribune. October 20, 1974. p. 42. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zebra Trial Delayed". Santa Cruz Sentinel. November 13, 1974. p. 7. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zebra Killings Witness Recants". San Mateo County Times. February 21, 1975. p. 20. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zebra Suit Seeks $14 Million". San Mateo County Times. February 25, 1975. p. 6. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "48 jurors excused in Day One of Zebra trial". San Francisco Examiner. March 4, 1975. p. 36. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jurors for Zebra Trial Selected". Oakland Tribune. March 29, 1975. p. 2. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "SF Zebra Trial Opens With Display of Pistol". San Mateo County Times. April 15, 1975. p. 5. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Grisly Testimony At Zebra Trial". Santa Cruz Sentinel. April 17, 1975. p. 3. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Death Angels' Initiation Rites Are Described". Santa Cruz Sentinel. April 18, 1975. p. 14. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Police threat story untrue, witness says". Independent, Long Beach. April 22, 1975. p. 31. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zebra gun sale admitted". Press-Telegram. May 6, 1975. p. 44. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Girl Identifies Zebra Suspect". Santa Cruz Sentinel. May 8, 1975. p. 26. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zebra Confession Heard By Jury". Santa Cruz Sentinel. May 21, 1975. p. 46. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zebra Jury Told About Shooting". San Mateo County Times. July 1, 1975. p. 6. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zebra Trial To Go To Jury". Santa Cruz Sentinel. February 9, 1976. p. 22. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Zebra Case Is Handed To Jury After 212 Days". Santa Cruz Sentinel. March 11, 1976. p. 2. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Four Are Guilty In Zebra Trial". Santa Cruz Sentinel. March 14, 1976. p. 1. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Four Are Guilty In Zebra Trial pt 2". Santa Cruz Sentinel. March 14, 1976. p. 2. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Life Sentences For Zebra Slayers". Santa Cruz Sentinel. March 30, 1976. p. 11. Retrieved December 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ msn.com.

- ^ mercurynews.com/2020/01/28/last-two-living-zebra-killers-denied-parole-tied-to-massive-california-murder-spree-targeting-whites-at-random/

- ^ Jessie Lee Cooks, convicted of "Zebra" killings, dies in prison, July 1, 2021

- ^ "Last surviving 'death angel' convicted of racist killings that tormented San Francisco in the 1970s loses latest bid for parole - San Francisco Public Safety News". sfpublicsafety.news. July 31, 2024. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- "4 Whites Killed by Roving Gunmen – At Least One Other Injured in San Francisco Area". The New York Times. UPI. January 30, 1974. p. 69. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- "CDCR Public Inmate Locator". Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- "Fear in the Streets of San Francisco". Time. April 29, 1974. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved August 28, 2006.

- Howard, Clark (1979). Zebra: The True Account of the 179 Days of Terror in San Francisco. New York: Richard Marek Publishers. ISBN 978-0-399-90050-1 – via Internet Archive.

- Peele, Thomas (February 7, 2012). Killing the Messenger: A Story of Radical Faith, Racism's Backlash, and the Assassination of a Journalist. Crown/Archetype. ISBN 978-030771757-3.

- Reports of Cases Determined in the Courts of Appeal of the State of California. Bancroft-Whitney. January 1, 1983. p. 268.

- Romney, Lee (March 13, 2015). "'Zebra Killer' J.C.X. Simon found dead in San Quentin prison cell". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- Sanders, Prentice Earl; Cohen, Bennett (2006). Zebra Murders: A Season of Killing, Racial Madness, and Civil Rights. New York: Arcade. ISBN 978-1-55970-806-7 – via Internet Archive.

- Scheeres, Julia. "The Zebra Killers". CrimeLibrary. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- Talbot, David (May 8, 2012). Season of the Witch: Enchantment, Terror and Deliverance in the City of Love. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-143912787-2.

- West's California reporter. Vol. 190. January 1, 1983. pp. 260–62.

- "'Zebra' cult killings rite?". Boca Raton News. UPI. May 2, 1974a. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- "'Zebra Killer' J.C.X. Simon found dead in San Quentin prison cell". msn.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

External links

[edit]- "S.F.'s own time of terror", sfgate.com; accessed March 15, 2015.

- Zebra, online ebook

- Unidentified victim at NamUs

- 1973 in California

- 1973 in San Francisco

- 1973 murders in the United States

- 1974 in California

- 1974 in San Francisco

- 1974 murders in the United States

- Crimes in San Francisco

- Murder in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Nation of Islam

- Racially motivated violence against white Americans

- Serial killers from California

- Serial murders in the United States

- Stabbing attacks in the United States