Betawi language

| Betawi | |

|---|---|

| basè Betawi, basa Betawi | |

| Native to | Indonesia |

| Region | Greater Jakarta |

| Ethnicity | |

Native speakers | (5 million cited 2000 census)[1] |

Malay-based creole

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin (Malay alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | bew |

| Glottolog | beta1252 |

| |

Betawi, also known as Batavian[2], Jakartanese[3], Betawi Malay, Jakartan Malay, or Batavian Malay, is the spoken language of the Betawi people in Jakarta, Indonesia. It is the native language of perhaps 5 million people; a precise number is difficult to determine due to the vague use of the name.

Betawi Malay is a popular informal language in contemporary Indonesia, used as the base of Indonesian slang and commonly spoken in Jakarta TV soap operas and some animated cartoons (e.g. Adit Sopo Jarwo).[4] The name "Betawi" stems from Batavia, the official name of Jakarta during the era of the Dutch East Indies. Colloquial Jakarta Indonesian, a vernacular form of Indonesian that has spread from Jakarta into large areas of Java and replaced existing Malay dialects, has its roots in Betawi Malay. According to Uri Tadmor, there is no clear border distinguishing Colloquial Jakarta Indonesian from Betawi Malay.[5]

Betawi is still spoken by the older generation in some locations on the outskirts of Jakarta, such as Kampung Melayu, Pasar Rebo, Pondok Gede, Ulujami, and Jagakarsa.[6]

There is a significant Chinese community which lives around Tangerang, called Cina Benteng, who have stopped speaking Chinese and now speak Betawian Malay with noticeable influence of Chinese (mostly Hokkien) loanwords.

Background

[edit]The origin of Betawi is of debate to linguists; many consider it to be a Malay dialect descended from Proto-Malayic, while others consider it to have developed as a creole. It is believed that descendants of Chinese men and Balinese women in Batavia converted to Islam and spoke a pidgin that was later creolized, and then decreolized incorporating many elements from Sundanese and Javanese (Uri Tadmor 2013).[7]

Betawi has large amounts of Hokkien Chinese, Arabic, Portuguese, and Dutch loanwords. Especially the Indonesian Arabic variation which greatly influences the vocabulary in this language.[8] It replaced the earlier Portuguese creole of Batavia, Mardijker. The first-person pronoun gua ('I' or 'me') and second-person pronoun lu ('you') and numerals such as cepé' ('a hundred'), gopé' ('five hundred'), and secèng ('a thousand') are from Hokkien, whereas the words anè ('I' or 'me') and énté ('you') are derived from Arabic. Cocos Malay, spoken in the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Australia and Sabah, Malaysia is believed to have derived from an earlier form of Betawi Malay.

Dialects

[edit]

There is no absolute consensus among linguists regarding the classification of the varieties of Batavian language. The most popular classification divides Batavian into two varieties (dialects or subdialects)[9], i.e.:

- Middle Batavian or Urban Batavian dialect (Betawi Tengah or Betawi Kota): originally spoken within the Urban Jakarta region, which is mainly characterized by an obvious realization of final [a] to [ɛ], e.g.: ada [ada] (Malay) 'to be (existence)' → adè [adɛ].

- Suburban Batavian or Ora Batavian dialect (Betawi Pinggiran or Betawi Ora): originally spoken in suburban Jakarta, Tangerang in Banten, Depok, Bogor, and Bekasi in West Java, which is characterized by the retention of final [a] or a change into [ah], e.g. gua [gua] or guah [guah] 'I, me' instead of guè [guɛ], and the use of ora 'no, not' as a negation particle instead of kaga' which is used in the Middle dialect.

Chaer (1982) divided the language into four subdialects, which are based mainly on—but not limited to—phonological realization variations[10], i.e.:

- Meester subdialect, spread across Jatinegara, Kampung Melayu, and the surrounding areas.

- Tanah Abang subdialect, spread across Tanah Abang, Petamburan, and the surrounding areas.

- Karet subdialect, spread across Karet, Senayan, Kuningan, Menteng and the surrounding areas.

- Kebayoran subdialect, spread across suburban and rural areas of the Batavian-speaking region.

The table below briefly describes the final sound realization variations between the subdialects drawn by Chaer (1982):

| Indonesian | Batavian | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meester | Tanah Abang | Karet | Kebayoran | ||||||

| [ah] | rumah [rumah] 'house' | [ɛ] | rumè [rumɛ] | [ɤː] | rume [rumɤː] | [a] | ruma [ruma] | [ah] | rumah [rumah] |

| [a] | bawa [bawa] 'to bring' | [ɛ] | bawè [bawɛ] | [ɤː] | bawe [bawɤː] | [ɛʔ] | bawè' [bawɛʔ] | [aʔ] | bawa' [bawaʔ] |

| saya [saja] 'I, me' | [ɛ] | sayè [sajɛ] | [ɤː] | saye [sajɤː] | [ɛ] | sayè [sajɛ] | [ah] | sayah [sajah] | |

| [ai̯] | satai [satai̯] 'satay' | [e] | saté [sate] | [e] | saté [sate] | [eʔ] | saté' [sateʔ] | [ɛʔ] | satè' [satɛʔ] |

| ramai [ramai̯] 'crowded' | [ɛ] | ramè [ramɛ] | [ɛ] | ramè [ramɛ] | [ɛ] | ramè [ramɛ] | [ɛ] | ramè [ramɛ] | |

| [ɛh] | boleh [bolɛh] 'may, might' | [ɛ] | bolè [bɔlɛ] | [e] | bolé [bɔle] or [bole] | [e] | bolé [bɔle] or [bole] | [eh] or [ɛh] | boléh [bɔleh] or bolèh [bɔlɛh] |

| [oh] | bodoh [bodoh] 'fool' | [ɔ] or [o] | bodo [bɔdɔ] or [bodo] | [ɔ] or [o] | bodo [bɔdɔ] or [bodo] | [ɔ] or [o] | bodo [bɔdɔ] or [bodo] | [ɔʔ] | bodo' [bɔdɔʔ] |

| [uh] | bunuh [bunuh] 'to kill' | [u] | bunu [bunu] | [u] | bunu [bunu] | [u] | bunu [bunu] | [uh] | bunuh [bunuh] |

| [u] | minggu [miŋɡu] 'week' | [u] | minggu [miŋɡu] | [u] | minggu [miŋɡu] | [uʔ] | minggu' [miŋɡuʔ] | [uʔ] | minggu' [miŋɡuʔ] |

However, Chaer (2015) also made a classification of dialectal variations based on the typology of Batavian subgroups, which is divided into three dialectal variations[11], i.e.:

- Urban variation (Betawi Kota or Betawi Tengah)

- Sububrban variation

- Rural variation (Betawi Ora')

Apart from a geographical basis, this typology is also based on final phoneme realization variations. This table describes the differences between these variations as cited in Chaer (2015).[12]

| Indonesian | Batavian | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Suburban | Rural | |||||

| [a] | apa [apa] 'what' | [ɛ] | apè [apɛ] | [ɛ] | apè [apɛ] | [ah] | apah [apah] |

| [ah] | salah [salah] 'mistaken' | [ɛ] | salè [salɛ] | [a] | sala [sala] | [ah] | salah [salah] |

Meanwhile, Grijns (1991) drew the classification into 7 distinct dialects (or dialect clusters).[13] These dialectal differences are drawn not only based on phonological realization variations—unlike other classifications that are mainly focused only on these phonological realization variations of final sounds—but also based on morphological and lexical differences (including lexical compatibility with other languages, such as Balinese, Javanese, Malay, and Sundanese). This is the classification of the dialects:

- Urban Jakarta Malay dialect: spoken mainly within the urban area of Jakarta. The most conspicuous feature of this dialect is the occurrence of è [ɛ] as the realization of the final diaphoneme a [a], e.g.: berapa [bərapa] 'how many, how much' → berapè [bərapɛ]. From a lexical compatibility aspect, this language has a high lexical compatibility with Malay and Indonesian. Javanese and Sundanese influences are roughly almost equal while Balinese is not dominant.

- Cengkareng-Grogol Petamburan-Kebayoran Baru dialect: spoken in several parts of West Jakarta and Senayan. From a lexical compatibility aspect, Javanese and Sundanese influences are roughly equal. However, lexical compatibility with Malay is lower, while Balinese influence is insignificant. Another typical feature of this dialect is the realization of the final diaphoneme a [a] with e [ə] (schwa) in several places belonging to this dialect, e.g.: {dia [dia] 'how many, how much' → die [diə].

- Pasar Rebo dialect: spoken in several parts of East Jakarta, especially in the Pasar Rebo, Pulo Gadung and the surrounding areas. Lexically, this dialect has roughly almost equal Javanese and Sundanese influences with a few Malay influences.

- Ciputat dialect: spoken across the western part of the Batavian-speaking region, comprising the Ciputat, South Tangerang, Depok, and several parts of Northern Bogor. Lexically, Javanese influence is higher than Sundanese influence, although the difference is not significant.

- Gunung Sindur dialect: spoken in the southwestern part of the Batavian-speaking region, especially in the Gunung Sindur region. The Sundanese influence is dominant in this dialect, followed by Javanese influence.

- Pebayuran dialect: spoken in the eastern part of the Batavian-speaking region, mainly in Bekasi region. The main distinct feature of this dialect is a strong Sundanese influence, both lexically and morphologically. Javanese influence is less prevalent than Sundanese, while Malay influence is insignificant.

- Mauk-Sepatan dialect: spoken in the northeastern part of the Batavian-speaking region, precisely in the Mauk and Sepatan which are located on the northern coast of Tangerang Regency. Despite high Banten Javanese and Sundanese influences, the lexical compatibility with Malay/Indonesian is also high.

However, Von de Wall (1909) also noted a dialect of the Batavian language, which has the visible feature of the final a [a] realization as ĕ [ə].[14] The usage of this "older" dialect started to fade later and to be replaced gradually with è [ɛ].[15] In 1971, Grijns (1991) could still witness a consistent realization of ĕ [ə] in Kebon Pala.[15] Here is an example of this dialect usage:

| Batavian of the ĕ [ə] dialect[16] | English translation |

|---|---|

| Njòءlĕ, naèk, kitĕ pĕlĕsiran. Poelang-poelang… malĕm; pedoeli apĕ, tĕrèm bĕdjalan hampé tĕngĕ malĕm boetĕ. Goewĕ rasĕ hampé poekoel hatoe.[a] | Come on! Get in! Let's have fun. It will be late at night once we get home. Who cares? The tram operates until midnight. I think it's until 1 o'clock. |

| |

Even though the Urban Jakarta dialect with its final è [ɛ] realization stereotypes the Batavian language throughout Indonesia,[17] there is no concept of a certain regional dialect being considered as "higher" or "more prestigious" than the other dialects among Batavians.[18] However, dialect-mixing is also found in some cases, especially on social media posts.[19]

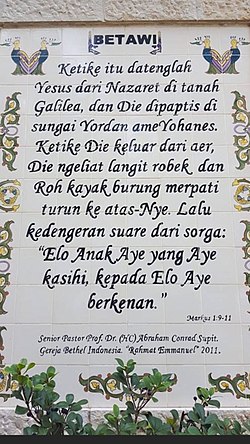

Sample

[edit]

Middle Betawi

[edit]Semuè orang, mah, èmang diberocotin ènggal amè ngelè argè diri amè hak-hak nyang sembabad. Tu orang padè diangsrongin deri sononya pikiran amè liangsim mengkènyè udè kudunyè, dèh, padè segalang-segulung nyampur amè nyang laènnyè dengen sumanget sudaraan.

Suburban Betawi

[edit]Orang dari sonohnya, mah, èmang diberocotinnya pada bébas ama gableg arga diri ama hak nyang sembabad. Tu orang udah dikasi pikiran ama liangsim mangkanya udah kudunya, dah, tuh, pada gaul campur dengen semanget sedaraan.[citation needed]

English

[edit]All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Indonesian

[edit]Semua manusia dilahirkan bebas dan samarata dari segi kemuliaan dan hak-hak. Mereka mempunyai pemikiran dan perasaan hati dan hendaklah bertindak di antara satu sama lain dengan semangat persaudaraan.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Betawi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Batavian at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Stevens, Alan M.; Schmidgall-Tellings, A. Ed. (2010). A Comprehensive Indonesian English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. p. 131.

- ^ Bowden, John. Towards an account of information structure in Colloquial Jakarta Indonesian. Proceedings of the International Workshop on Information Structure of Austronesian Languages, 10 April 2014. Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. p. 194.

- ^ Kozok, Uli (2016), Indonesian Native Speakers – Myth and Reality (PDF), p. 15

- ^ "Documentation of Betawi". Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ Tadmor, Uri (2013). "On the Origin of the Betawi and their Language" (PDF). ISMIL 17 conference talk.

- ^ Rahman, Lina Aulia (2021). "Kebudayaan Masyarakat Keturunan Arab Di Jakarta, Studi Kasus di Kampung Arab Condet" (PDF). Program Studi Magister Kajian Timur Tengah dan Islam (in Indonesian). Jakarta, Indonesia: University of Indonesia. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ Muhadjir (1984). Morfologi Dialek Jakarta: Afiksasi dan Reduplikasi [Morphology of Jakarta Dialect] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Penerbit Djambatan. p. 4.

- ^ Chaer, Abdul (1982). Kamus Dialek Jakarta [Dictionary of Jakarta Dialect] (in Indonesian). Ende: Penerbit Nusa Indah. p. xviii–xix.

- ^ Chaer, Abdul (2015). Betawi Tempo Doeloe: Menelusuri Sejarah Kebudayaan Betawi [Batavia in the Past: Exploring the History of Batavian Culture] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Penerbit Masup Jakarta. p. 14-16, 75-78.

- ^ Chaer 2015, p. 75-78.

- ^ Grijns, C. D. (1991). Jakarta. Vol. 1. Leiden: KITLV Press. p. 199-246.

- ^ von Dewall, A. (1909). "Bataviaasch-Maleische Taalstudiën" [Batavian Malay Language Study] (PDF). Tijdschrift voor Indische taal-, land- en volkenkunde (in Dutch). 51. Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen: 191–221.

- ^ a b Grijns 1991, p. 211.

- ^ von Dewall 1909, p. 211.

- ^ Grijns 1991, p. 204.

- ^ Chaer 1982, p. xx.

- ^ Nanda, R. A. (2025). Sikap Bahasa dalam Lanskap Linguistik Posting-an Akun Instagram Bertemakan Kebudayaan Betawi [Language Attitude in the Linguistic Landscape of Batavian Culture-related Instagram Accounts' Posts] (Master's thesis). Depok: University of Indonesia. p. 43, 47.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ikranagara, Kay (1975). Melayu Betawi grammar (Ph. D. thesis). University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/11720.