Climate crisis

Climate crisis is a term that is used to describe global warming and climate change and their effects. This term and the term climate emergency have been used to emphasize the threat of global warming to Earth's natural environment and to humans, and to urge aggressive climate change mitigation and transformational adaptation.[2][3][4][5]

The term climate crisis is used by those who "believe it evokes the gravity of the threats the planet faces from continued greenhouse gas emissions and can help spur the kind of political willpower that has long been missing from climate advocacy".[2] They believe, much as global warming provoked more emotional engagement and support for action than climate change,[2][6][7] calling climate change a crisis could have an even stronger effect.[2]

A study has shown the term climate crisis invokes a strong emotional response by conveying a sense of urgency.[8] However, some caution this response may be counter-productive[9] and may cause a backlash due to perceptions of alarmist exaggeration.[10][11]

In the scientific journal BioScience, a January 2020 article that was endorsed by over 11,000 scientists states: "the climate crisis has arrived" and that an "immense increase of scale in endeavors to conserve our biosphere is needed to avoid untold suffering due to the climate crisis".[12][13]

Scientific basis

[edit]

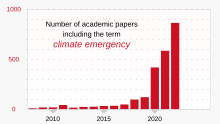

Until the mid 2010s, the scientific community had been using neutral, constrained language when discussing climate change. Advocacy groups, politicians and media have traditionally been using more-powerful language than that used by climate scientists.[18] From around 2014, a shift in scientists' language connoted an increased sense of urgency.[19]: 2546 Use of the terms urgency, climate crisis and climate emergency in scientific publications and in mass media has grown. Scientists have called for more-extensive action and transformational climate-change adaptation that focuses on large-scale change in systems.[19]: 2546

In 2020, a group of over 11,000 scientists said in a paper in BioScience describing global warming as a climate emergency or climate crisis was appropriate.[20] The scientists stated an "immense increase of scale in endeavor" is needed to conserve the biosphere.[12] They warned about "profoundly troubling signs", which may have many indirect effects such as large-scale human migration and food insecurity; these signs include increases in dairy and meat production, fossil fuel consumption, greenhouse gas emissions and deforestation, activities that are all concurrent with upward trends in climate-change effects such as rising global temperatures, global ice melt and extreme weather.[12]

In 2019, scientists published an article in Nature saying evidence from climate tipping points alone suggests "we are in a state of planetary emergency".[21] They defined emergency as a product of risk and urgency, factors they said are "acute". Previous research had shown individual tipping points could be exceeded with a 1–2 °C (1.8–3.6 °F) of global temperature increase; warming has already exceeded 1 °C (1.8 °F).[21] A global cascade of tipping points is possible with greater warming.[21]

Definitions

[edit]In the context of climate change, the word crisis is used to denote "a crucial or decisive point or situation that could lead to a tipping point".[5] It is a situation with an "unprecedented circumstance".[5] A similar definition states in this context, crisis means "a turning point or a condition of instability or danger" and implies "action needs to be taken now or else the consequences will be disastrous".[22] Another definition defines climate crisis as "the various negative effects that unmitigated climate change is causing or threatening to cause on our planet, especially where these effects have a direct impact on humanity".[11]

Use of the term

[edit]

20th century

[edit]

Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore has used crisis terminology since the 1980s; the Climate Crisis Coalition, which was formed in 2004, formalized the term climate crisis.[2] A 1990 report by the American University International Law Review includes legal texts that use the word crisis.[3] "The Cairo Compact: Toward a Concerted World-Wide Response to the Climate Crisis" (1989) states: "All nations ... will have to cooperate on an unprecedented scale. They will have to make difficult commitments without delay to address this crisis."[3]

21st century

[edit]

Call It a Climate Crisis —

and Cover It Like One

The words that reporters and anchors use matter. What they call something shapes how millions see it—and influences how nations act. And today, we need to act boldly and quickly. With scientists warning of global catastrophe unless we slash emissions by 2030, the stakes have never been higher, and the role of news media never more critical.

We are urging you to call the dangerous overheating of our planet, and the lack of action to stop it, what it is—a crisis––and to cover it like one.

Public Citizen open letter

June 6, 2019[24]

In the late 2010s, the phrase climate crisis emerged "as a crucial piece of the climate hawk lexicon", and was adopted by the Green New Deal, The Guardian, Greta Thunberg, and U.S. Democratic political candidates such as Kamala Harris.[2] At the same time, it came into more-popular use following a series of warnings from climate scientists and newly-energized activists.[2]

In the U.S. in late 2018, the United States House of Representatives established the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, the name of which was regarded as "a reminder of how much energy politics have changed in the last decade".[25] The original House climate committee had been called the "Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming" in 2007.[2] It was abolished in 2011 when Republicans regained control of the House.[4]

The advocacy group Public Citizen reported that in 2018, less than 10% of articles in top-50 U.S. newspapers used the terms crisis or emergency in the context of climate change.[26] In the same year, 3.5% of national television news segments in the U.S. referred to climate change as a crisis or an emergency (50 of 1,400).[26][27] In 2019, Public Citizen launched a campaign called "Call it a Climate Crisis"; it urged major media organizations to adopt the term climate crisis.[27] In the first four months of 2019, the number of uses of the term in U.S. media tripled to 150.[26] Likewise, the Sierra Club, the Sunrise Movement, Greenpeace, and other environmental and progressive organizations joined in a June 6, 2019 Public Citizen letter to news organizations[26] urging the news organizations to call climate change and human inaction "what it is–a crisis–and to cover it like one".[24]

We cannot solve a crisis without treating it as a crisis. Nor can we treat something like a crisis unless we understand the emergency.

Greta Thunberg, December 10, 2020[28]

In 2019, the language describing climate appeared to change: the UN Secretary General's address at the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit used more emphatic language; Al Gore's campaign The Climate Reality Project, Greenpeace and the Sunrise Movement petitioned news organizations to alter their language; and in May 2019, The Guardian changed its style guide[29] to favor the terms "climate emergency, crisis or breakdown" and "global heating".[30][31] Editor-in-Chief Katharine Viner said: "We want to ensure that we are being scientifically precise, while also communicating clearly with readers on this very important issue. The phrase 'climate change', for example, sounds rather passive and gentle when what scientists are talking about is a catastrophe for humanity."[32] The Guardian became a lead partner in Covering Climate Now, an initiative of news organizations Columbia Journalism Review and The Nation that was founded in 2019 to address the need for stronger climate coverage.[33][34]

In May 2019, The Climate Reality Project promoted an open petition of news organizations to use climate crisis instead of climate change and global warming.[2] The NGO said: "it's time to abandon both terms in culture".[35]

In June 2019, Spanish news agency EFE announced its preferred phrase was "crisis climática".[26] In November 2019, Hindustan Times also adopted the term because climate change "does not correctly reflect the enormity of the existential threat".[36] The Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza also uses the term climate crisis rather than climate change; one of its editors described climate change as one of the most-important topics the paper has ever covered.[37]

Also in June 2019, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) changed its language guide to say: "Climate crisis and climate emergency are OK in some cases as synonyms for 'climate change'. But they're not always the best choice ... For example, 'climate crisis' could carry a whiff of advocacy in certain political coverage".[38] Journalism professor Sean Holman does not agree with this and said in an interview:

It's about being accurate in terms of the scope of the problem that we are facing. And in the media we, generally speaking, don't have any hesitation about naming a crisis when it is a crisis. Look at the opioid epidemic [in the U.S.], for example. We call it an epidemic because it is one. So why are we hesitant about saying the climate crisis is a crisis?[38]

In June 2019, climate activists demonstrated outside the offices of The New York Times; they urged the newspaper's editors to adopt terms such as climate emergency or climate crisis. This kind of public pressure led New York City Council to make New York the largest city in the world to formally adopt a climate emergency declaration.[39]

In November 2019, the website Oxford Dictionaries named climate crisis Word of the year for 2019. The term was chosen because it matches the "ethos, mood, or preoccupations of the passing year".[40]

In 2021, the Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat created a free variable font called Climate Crisis that has eight weights that correlate with Arctic sea ice decline, visualizing historical changes in ice melt.[41] The newspaper's art director said the font both evokes the aesthetics of environmentalism and is a data visualization graphic.[41]

In updates to the World Scientists' Warning to Humanity of 2021 and 2022, scientists used the terms climate crisis and climate emergency; the title of the publications is "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency".[13][42] They said: "we need short, frequent, and easily accessible updates on the climate emergency".[13]

Effectiveness

[edit]In September 2019, Bloomberg journalist Emma Vickers said crisis terminology may be "showing results", citing a 2019 poll by The Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Foundation saying 38% of U.S. adults termed climate change "a crisis" while an equal number called it "a major problem but not a crisis".[4] Five years earlier, 23% of U.S. adults considered climate change to be a crisis.[43] As of 2019[update], use of crisis terminology in non-binding climate-emergency declarations is regarded as ineffective in making governments "shift into action".[5]

Concerns about crisis terminology

[edit]Emergency framing may have several disadvantages.[9] Such framing may implicitly prioritize climate change over other important social issues, encouraging competition among activists rather than cooperation. It could also de-emphasize dissent within the climate-change movement.[9] Emergency framing may suggest a need for solutions by government, which provides less-reliable long-term commitment than does popular mobilization, and which may be perceived as being "imposed on a reluctant population".[9] Without immediate dramatic effects of climate change, emergency framing may be counterproductive by causing disbelief, disempowerment in the face of a problem that seems overwhelming, and withdrawal.[9]

There could also be a "crisis fatigue" in which urgency to respond to threats loses its appeal over time.[18] Crisis terminology could lose audiences if meaningful policies to address the emergency are not enacted.[18] According to researchers Susan C. Moser and Lisa Dilling of University of Colorado, appeals to fear usually do not create sustained, constructive engagement; they noted psychologists consider human responses to danger—fight, flight or freeze—can be maladaptive if they do not reduce the danger.[44] According to Sander van der Linden, director of the Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab, fear is a "paralyzing emotion". He favors climate crisis over other terms because it conveys a sense of both urgency and optimism, and not a sense of doom. Van der Linden said: "people know that crises can be avoided and that they can be resolved".[45]

Climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe said in early 2019 crisis framing is only "effective for those already concerned about climate change, but complacent regarding solutions".[11] She added it "is not yet effective" for those who perceive climate activists "to be alarmist Chicken Littles", and that "it would further reinforce their pre-conceived—and incorrect—notions".[11] According to Nick Reimer, journalists in Germany say the word crisis may be misunderstood to mean climate change is "inherently episodic"—crises are "either solved or they pass"—or as a temporary state before a return to normalcy that is not possible.[46] Arnold Schwarzenegger, organizer of the Austrian World Summit for climate action[failed verification], said people are not motivated by the term climate change; according to Schwarzenegger, focusing on the word pollution might evoke be a more-direct and negative connotation.[47] A 2023 U.S. survey found no evidence that climate crisis or climate emergency—terms less familiar to those surveyed—elicit more perceived urgency than climate change or global warming.[48]

Psychological and neuroscientific studies

[edit]In 2019, an advertising consulting agency conducted a neuroscientific study involving 120 U.S. people who were equally divided into supporters of the Republican Party, the Democratic Party and independents.[49] The study involved electroencephalography (EEG) and galvanic skin response (GSR) measurements.[8] Responses to the terms climate crisis, environmental destruction, environmental collapse, weather destabilization, global warming and climate change were measured.[49] The study found Democrats had a 60% greater emotional response to climate crisis than to climate change. In Republicans, the emotional response to climate crisis was three times stronger than that for climate change.[49] According to CBS News, climate crisis "performed well in terms of responses across the political spectrum and elicited the greatest emotional response among independents".[49] The study concluded climate crisis elicited stronger emotional responses than neutral and "worn out" terms like global warming and climate change.[8] Climate crisis was found to encourage a sense of urgency, though not a strong-enough response to cause cognitive dissonance that would cause people to generate counterarguments.[8]

Related terminology

[edit]Climate change is here. It is terrifying. And it is just the beginning. The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived.

— António Guterres, U.N. Secretary-General[50]

27 July 2023

Research has shown the naming of a phenomenon and the way it is framed "has a tremendous effect on how audiences come to perceive that phenomenon"[10] and "can have a profound impact on the audience's reaction".[45] Climate change, and its real and hypothetical effects, are usually described in scientific-and-practitioner literature in terms of climate risks.

The many related terms other than climate crisis include:[a]

- climate catastrophe (used with reference to a 2019 David Attenborough documentary,[52] the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season,[53] and the 2022 Pakistan floods[54])

- threats that impact the earth (World Wildlife Fund, 2012—)[55]

- climate breakdown (climate scientist Peter Kalmus, 2018)[56]

- climate chaos ("The New York Times" article title, 2019;[57] U.S. Democratic candidates, 2019;[58] and an Ad Age marketing team, 2019)[45]

- climate ruin (U.S. Democratic candidates, 2019)[58]

- global heating (Richard A. Betts, Met Office U.K., 2018)[59]

- global overheating (Public Citizen, 2019)[24]

- climate emergency (11,000 scientists' warning letter[12] in BioScience,[60][61] and in The Guardian,[4][30] both 2019),

- ecological breakdown, ecological crisis and ecological emergency (all set forth by climate activist Greta Thunberg, 2019)[62]

- global meltdown, Scorched Earth, The Great Collapse, and Earthshattering (an Ad Age marketing team, 2019)[45]

- climate disaster (The Guardian, 2019)[63]

- environmental Armageddon (Fiji Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama)[64]

- climate calamity (Los Angeles Times, 2022)[65]

- climate havoc (The New York Times, 2022)[66]

- climate pollution, carbon pollution (Grist, 2022)[67]

- global boiling (U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres speech, July 2023)[50]

- climate breaking point (Stuart P.M. Mackintosh, The Hill, August 2023)[68]

- (Has humanity) broken the climate (The Guardian, August 2023)[69]

- (climate) abyss (spokesman for the United Nations secretary general, May 2024)[70]

- climate hell (U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres, June 2024)[71]

In addition to climate crisis, other terms have been investigated for their effects upon audiences, including global warming, climate change, climatic disruption,[10] environmental destruction, weather destabilization and environmental collapse.[8]

In 2022, The New York Times journalist Amanda Hess said "end of the world" characterizations of the future, such as climate apocalypse, are often used to refer to the current climate crisis, and that the characterization is spreading from "the ironized hellscape of the internet" to books and film.[72]

See also

[edit]- Climate psychology – Field of psychology

- Environmental communication – Type of communication

- Extinction Rebellion – Environmental pressure group

- Media coverage of climate change

- Psychology of climate change denial – Human behaviour with regards to climate change denial

- Public opinion on climate change – Aspect of worldwide public opinion

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Following dates are not necessarily the first use of such terms.

References

[edit]- ^ Rosenblad, Kajsa (December 18, 2017). "Review: An Inconvenient Sequel". Medium (Communication Science news and articles). Netherlands. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019.

... climate change, a term that Gore renamed to climate crisis

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sobczyk, Nick (July 10, 2019). "How climate change got labeled a 'crisis'". E & E News (Energy & Environmental News). Archived from the original on October 13, 2019.

- ^ a b c Center for International Environmental Law. (1990). "Selected International Legal Materials on Global Warming and Climate Change". American University International Law Review. 5 (2): 515. Archived from the original on June 23, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Vickers, Emma (September 17, 2019). "When Is Change a 'Crisis'? Why Climate Terms Matter". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Mukheibir, Pierre; Mallam, Patricia (September 30, 2019). "Climate crisis – what's it good for?". The Fifth Estate. Australia. Archived from the original on October 1, 2019.

- ^ Samenow, Jason (January 29, 2018). "Debunking the claim 'they' changed 'global warming' to 'climate change' because warming stopped". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019.

- ^ Maibach, Edward; Leiserowitz, Anthony; Feinberg, Geoff; Rosenthal, Seth; Smith, Nicholas; Anderson, Ashley; Roser-Renouf, Connie (May 2014). "What's in a Name? Global Warming versus Climate Change". Yale Project on Climate Change, Center for Climate Change Communication. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.10123.49448. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Yoder, Kate (April 29, 2019). "Why your brain doesn't register the words 'climate change'". Grist. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Hodder, Patrick; Martin, Brian (September 5, 2009). "Climate Crisis? The Politics of Emergency Framing" (PDF). Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (36): 53, 55–60. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 10, 2020.(subscription required)

- ^ a b c "Words That (Don't) Matter: An Exploratory Study of Four Climate Change Names in Environmental Discourse / Investigating the Best Term for Global Warming". naaee.org. North American Association for Environmental Education. 2013. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Dean, Signe (May 25, 2019). "ScienceAlert Editor: Yes, It's Time to Update Our Climate Change Language". Science Alert. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M.; Barnard, Phoebe; Moomaw, William R. (January 1, 2020). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency". BioScience. 70 (1): 8–12. doi:10.1093/biosci/biz088. hdl:2445/151800. ISSN 0006-3568. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M.; Gregg, Jillian W.; et al. (July 28, 2021). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency 2021". BioScience. 71 (9): biab079. doi:10.1093/biosci/biab079. hdl:10871/126814. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ Cook, John; Oreskes, Naomi; Doran, Peter T.; Anderegg, William R. L.; et al. (2016). "Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming". Environmental Research Letters. 11 (4): 048002. Bibcode:2016ERL....11d8002C. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002. hdl:1983/34949783-dac1-4ce7-ad95-5dc0798930a6.

- ^ Powell, James Lawrence (November 20, 2019). "Scientists Reach 100% Consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming". Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. 37 (4): 183–184. doi:10.1177/0270467619886266. S2CID 213454806. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ Lynas, Mark; Houlton, Benjamin Z.; Perry, Simon (October 19, 2021). "Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (11): 114005. Bibcode:2021ERL....16k4005L. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966. S2CID 239032360.

- ^ Myers, Krista F.; Doran, Peter T.; Cook, John; Kotcher, John E.; Myers, Teresa A. (October 20, 2021). "Consensus revisited: quantifying scientific agreement on climate change and climate expertise among Earth scientists 10 years later". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (10): 104030. Bibcode:2021ERL....16j4030M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2774. S2CID 239047650.

- ^ a b c Bedi, Gitanjali (January 3, 2020). "Is it time to rethink our language on climate change?". Monash Lens. Monash University (Melbourne, Australia). Archived from the original on January 31, 2020.

- ^ a b New, M., D. Reckien, D. Viner, C. Adler, S.-M. Cheong, C. Conde, A. Constable, E. Coughlan de Perez, A. Lammel, R. Mechler, B. Orlove, and W. Solecki, 2022: Chapter 17: Decision-Making Options for Managing Risk. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 2539–2654, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.026

- ^ Carrington, Damian (November 5, 2019). "Climate crisis: 11,000 scientists warn of 'untold suffering'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on January 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c Lenton, Timothy M.; Rockström, Johan; Gaffney, Owen; Rahmstorf, Stefan; Richardson, Katherine; Steffen, Will; Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim (2019). "Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against". Nature. 575 (7784): 592–595. Bibcode:2019Natur.575..592L. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03595-0. hdl:10871/40141. PMID 31776487. S2CID 208330359.

- ^ "What does climate crisis mean? / Where does climate crisis come from?". dictionary.com. December 2019. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019.

- ^ "United States House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis / About". climatecrisis.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. 2019. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Crediting Shawna Faison and House Creative Services.

- ^ a b c "Letter to Major Networks: Call it a Climate Crisis – and Cover it Like One". citizen.org. Public Citizen. June 6, 2019. Archived from the original on October 17, 2019.

- ^ Meyer, Robinson (December 28, 2018). "Democrats Establish a New House 'Climate Crisis' Committee". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Yoder, Kate (June 17, 2019). "Is it time to retire 'climate change' for 'climate crisis'?". Grist. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019.

- ^ a b "Call it a Climate Crisis". ActionNetwork.org. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Earliest Wayback Machine archive is May 17, 2019. - ^ Common Dreams (December 11, 2020). "Greta Thunberg Warns Humanity 'Still Speeding in Wrong Direction' on Climate". Ecowatch.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021.

- ^ Visram, Talib (December 6, 2021). "The language of climate is evolving, from 'change' to 'catastrophe'". Fast Company. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Hickman, Leo (May 17, 2019). "The Guardian's editor has just issued this new guidance to all staff on language to use when writing about climate change and the environment..." Journalist Leo Hickman on Twitter. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (May 17, 2019). "Why The Guardian is changing the language it uses about the environment". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (May 17, 2019). "Why The Guardian is changing the language it uses about the environment / From now, house style guide recommends terms such as 'climate crisis' and 'global heating'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019.

- ^ Guardian staff (April 12, 2021). "The climate emergency is here. The media needs to act like it". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021.

- ^ Hertsgaard, Mark (August 28, 2019). "Covering Climate Now signs on over 170 news outlets". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019.

- ^ "Why Do We Call It the Climate Crisis?". climaterealityproject.org. The Climate Reality Project. May 1, 2019. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019.

- ^ "Recognising the climate crisis". Hindustan Times. November 24, 2019. Archived from the original on November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Do European media take climate change seriously enough?". European Journalism Observatory (ejo.ch). Switzerland. February 18, 2020. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "Treat climate change like the crisis it is, says journalism professor". Interviewed by Gillian Findlay. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. July 5, 2019. Archived from the original on July 7, 2019. • Archive of CBC quote in Osoyoos Times.

- ^ Barnard, Anne (July 5, 2019). "A 'Climate Emergency' Was Declared in New York City. Will That Change Anything?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 11, 2019.

- ^ Zhou, Naaman (November 20, 2019). "Oxford Dictionaries declares 'climate emergency' the word of 2019". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. "Climate emergency" was named word of the year.

- ^ a b Smith, Lilly (February 16, 2021). "This chilling font visualizes Arctic ice melt". Fast Company. Archived from the original on February 23, 2021.

- ^ Ripple, William J; Wolf, Christopher; Gregg, Jillian W; Levin, Kelly; Rockström, Johan; Newsome, Thomas M; Betts, Matthew G; Huq, Saleemul; Law, Beverly E; Kemp, Luke; Kalmus, Peter; Lenton, Timothy M (October 26, 2022). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency 2022". BioScience. 72 (12): 1149–1155. doi:10.1093/biosci/biac083. hdl:1808/30278.

- ^ Guskin, Emily; Clement, Scott; Achenbach, Joel (December 9, 2019). "Americans broadly accept climate science, but many are fuzzy on the details". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019.

- ^ Moser, Susan C.; Dilling, Lisa (December 2004). "Making Climate Hot / Communicating the Urgency and Challenge of Global Climate Change" (PDF). University of Colorado. pp. 37–38. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 10, 2017. Footnotes 33–37. Also published: December 2004, Environment, volume 46, no. 10, pp. 32–46 Archived May 18, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d Rigby, Sara (January 3, 2020). "Climate change: should we change the terminology?". BBC Science Focus. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020.

- ^ Reimer, Nick (September 19, 2019). "Climate Change or Climate Crisis – What's the right lingo?". Germany. Clean Energy Wire. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019.

- ^ Shahan, Zachary (June 6, 2023). "Why Arnold Schwarzenegger Wants Us To Focus On Pollution Rather Than Climate Change". Clean Technica. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023.

- ^ de Bruin, Wandi Bruine; Kruke, Laurel; Sinatra, Gale M.; Schwarz, Norbert (August 12, 2024). "Should we change the term we use for "climate change"? Evidence from a national U.S. terminology experiment". Climactic Change. 177 (129). doi:10.1007/s10584-024-03786-3.

- ^ a b c d Berardelli, Jeff (May 16, 2019). "Does the term "climate change" need a makeover? Some think so — here's why". CBS News. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019.

- ^ a b "Secretary-General's opening remarks at press conference on climate". UN.org. United Nations. July 27, 2023. Archived from the original on July 29, 2023.

- ^ Osaka, Shannon (October 30, 2023). "Why many scientists are now saying climate change is an all-out emergency". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Data source: Web of Science database.

- ^ "Climate Change: The Facts". Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC Australia). August 2019. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019.

- ^ Flanagan, Richard (January 3, 2020). "Australia Is Committing Climate Suicide". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020.

- ^ Baloch, Shah Meer (August 28, 2022). "Pakistan declares floods a 'climate catastrophe' as death toll tops 1,000". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 28, 2022.

- ^ "Tackling Threats That Impact the Earth". World Wildlife Fund. 2019. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019.

- ^ Kalmus, Peter (August 29, 2018). "Stop saying 'climate change' and start saying 'climate breakdown.'". @ClimateHuman on Twitter. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019.

- ^ Shannon, Noah Gallagher (April 10, 2019). "Climate Chaos Is Coming — and the Pinkertons Are Ready". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Kormann, Carolyn (July 11, 2019). "The Case for Declaring a National Climate Emergency". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (December 16, 2018). "Global warming should be called global heating, says key scientist". Grist. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019.

- ^ Ryan, Jackson (November 5, 2019). "'Climate emergency': Over 11,000 scientists sound thunderous warning / The dire words are a call to action". CNET. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019.

- ^ McGinn, Miyo (November 5, 2019). "11,000 scientists say that the 'climate emergency' is here". Grist. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019.

- ^ Picazo, Mario (May 13, 2019). "Should we reconsider the term 'climate change'?". The Weather Network (CA). Archived from the original on November 12, 2019. includes link to Thunberg's tweet: ● Thunberg, Greta (May 4, 2019). "It's 2019. Can we all now please stop saying 'climate change' and instead call it what it is". twitter.com/GretaThunberg. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ Goldrick, Geoff (December 19, 2019). "2019 has been a year of climate disaster. Yet still our leaders procrastinate". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019.

- ^ Anna, Cara (September 27, 2020). "Leaders to UN: If virus doesn't kill us, climate change will". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023.

- ^ Roth, Sammy (July 28, 2022). "August is coming. Prepare for climate calamity". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022.

- ^ Sengupta, Somini (September 27, 2022). "Who pays for climate havoc?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022.

- ^ Yoder, Kate (September 29, 2022). "'It makes climate change real': How carbon emissions got rebranded as 'pollution'". Grist. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022.

- ^ Mackintosh, Stuart P. M. (August 22, 2023). "We need better strategies for the approaching climate breaking point". The Hill. Archived from the original on August 24, 2023.

- ^ Carrington, Damian; Lakhani, Nina; Milman, Oliver; Morton, Adam; Niranjan, Ajit; Watts, Johathan (August 28, 2023). "'Off-the-charts records': has humanity finally broken the climate?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 29, 2023.

- ^ Carrington, Demian (May 9, 2024). "'The stakes could not be higher': world is on edge of climate abyss, UN warns". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024.

- ^ "There is an exit off 'the highway to climate hell', Guterres insists". United Nations. June 5, 2024. Archived from the original on June 5, 2024.

- ^ Hess, Amanda (February 3, 2022). "Apocalypse When? Global Warming's Endless Scroll". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023.

the climate crisis is outpacing our emotional capacity to describe it.

(subscription required)

Further reading

[edit]- "Act now and avert a climate crisis (editorial)". Nature. September 15, 2019. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. (Nature joining Covering Climate Now.)

- Feldman, Lauren; Hart, P. Sol (November 16, 2021). "Upping the ante? The effects of "emergency" and "crisis" framing in climate change news". Climatic Change. 169 (10): 10. Bibcode:2021ClCh..169...10F. doi:10.1007/s10584-021-03219-5. S2CID 244119978.

- Hall, Aaron (November 27, 2019). "Renaming Climate Change: Can a New Name Finally Make Us Take Action". Ad Age. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. (advertising perspective by a "professional namer")

- Visram, Talib (December 6, 2021). "The language of climate is evolving, from 'change' to 'catastrophe'". Fast Company. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Covering Climate Now (CCNow), a collaboration among news organizations "to produce more informed and urgent climate stories" (archive)