Hurricane Maria

Maria near peak intensity while southeast of the U.S. Virgin Islands late on September 19 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 16, 2017 |

| Extratropical | September 30, 2017 |

| Dissipated | October 2, 2017 |

| Category 5 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 175 mph (280 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 908 mbar (hPa); 26.81 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 3,059 total |

| Damage | $91.6 billion (2017 USD) (Fourth-costliest tropical cyclone on record; costliest in Dominican and Puerto Rican history) |

| Areas affected |

|

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season | |

| History • Meteorological history Effects • Commons: Maria images | |

Hurricane Maria was an extremely powerful and devastating tropical cyclone that affected the northeastern Caribbean in September 2017, particularly in the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, which accounted for 2,975 of the 3,059 deaths.[1][2] It is the deadliest and costliest hurricane to strike the island of Puerto Rico, and is the deadliest hurricane to strike the country of Dominica and the territory of the U.S. Virgin Islands. The most intense tropical cyclone worldwide in 2017, Maria was the thirteenth named storm, eighth consecutive hurricane, fourth major hurricane, second Category 5 hurricane, and deadliest storm of the extremely active 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. With over 3,000 deaths and a minimum central pressure of 908 millibars (26.8 inHg), Maria was both the deadliest Atlantic hurricane since Jeanne in 2004, and the eleventh most intense Atlantic hurricane on record, respectively. Total monetary losses are estimated at upwards of $91.61 billion (2017 USD), almost all of which came from Puerto Rico, ranking it as the fourth-costliest tropical cyclone on record.

Maria developed from a tropical wave on September 16 east of the Lesser Antilles. Steady strengthening and organization took place initially, until favorable conditions enabled it to undergo explosive intensification on the afternoon of September 18, achieving Category 5 strength just before making landfall on the island of Dominica that night. After crossing the island and weakening slightly, Maria re-intensified and achieved its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 175 mph (280 km/h) and a pressure of 908 mbar (hPa; 26.81 inHg). On September 20, an eyewall replacement cycle weakened Maria to a high-end Category 4 hurricane by the time it struck Puerto Rico. The hurricane re-emerged weaker from land interaction, but quickly restrengthened back into a major hurricane again the following day. Passing north of The Bahamas, Maria remained a powerful hurricane over the following week as it slowly paralleled the East Coast of the United States, gradually weakening over time as conditions became less favorable. Maria then stalled and swung eastward over the open Atlantic, becoming extratropical on September 30 before dissipating by October 2.

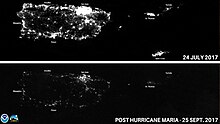

Maria brought catastrophic devastation to the entirety of Dominica, destroying housing stock and infrastructure beyond repair, and practically eradicating the island's lush vegetation. The neighboring islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique endured widespread flooding, damaged roofs, and uprooted trees. Puerto Rico suffered catastrophic damage and a major humanitarian crisis; most of the island's population suffered from flooding and a lack of resources, compounded by a slow relief process. The storm caused the worst electrical blackout in US history, which persisted for several months.[3] Maria also landed in the northeast Caribbean during relief efforts from another Category 5 hurricane, Irma, which crossed the region two weeks prior. The total death toll is 3,059: an estimated 2,975 in Puerto Rico,[4][5] 65 in Dominica, 5 in the Dominican Republic, 4 in Guadeloupe, 4 in the contiguous United States, 3 in the United States Virgin Islands, and 3 in Haiti. Maria was the deadliest hurricane in Dominica since the 1834 Padre Ruíz hurricane[6] and the deadliest in Puerto Rico since the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane.[7] This makes it the deadliest named Atlantic hurricane of the 21st century to date.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Maria originated from a tropical wave that left the western coast of Africa on September 12.[5] Gradual organization occurred as it progressed westward across the tropical Atlantic under the influence of a mid-level ridge that was located to the system's north,[8][9] and by 12:00 UTC on September 16, it had developed into Tropical Depression Fifteen, as deep convection consolidated and developed into curved bands wrapping into an increasingly-defined center of circulation. At that time, it was located about 665 mi (1,070 km) east of Barbados.[5] Favorable conditions along the system's path consisting of warm sea surface temperatures of 29 °C (84 °F), low wind shear, and abundant moisture aloft allowed the disturbance to consolidate and become Tropical Storm Maria 6 hours later, after satellite images had indicated that the low-level circulation of the wave had become well-defined.[5][10]

Maria gradually strengthened, and by late on September 17, although the center had temporarily become exposed, a convective burst over the center enabled it to become a hurricane.[11] Shortly afterward, explosive intensification occurred, with Maria nearly doubling its winds from 85 mph (140 km/h)—a Category 1 hurricane, to 165 mph (270 km/h)—a Category 5 hurricane, in just 24 hours, by which time it was located just 15 mi (24 km) east-southeast of Dominica late on September 18;[5][12] the rate of intensification that occurred has been exceeded only a few times in the Atlantic since records began. Maria made landfall in Dominica at 01:15 UTC on September 19,[13] becoming the first Category 5 hurricane on record to strike the island nation.[14]

Entering the Caribbean Sea, Maria weakened slightly to a Category 4 hurricane due to land interaction with the island of Dominica, however it quickly restrengthened to a Category 5 hurricane and attained its peak intensity with winds of 175 mph (280 km/h) and a pressure of 908 mbar (hPa; 26.81 inHg) at 03:00 UTC on September 20 while southeast of Puerto Rico; this ranks it as the eleventh-most intense Atlantic hurricane since reliable records began.[5] An eyewall replacement cycle caused Maria weaken to Category 4 strength before it made landfall near Yabucoa, Puerto Rico at 10:15 UTC (6:15 am local time) that day with winds of 155 mph (250 km/h)—the most intense to strike on the island since the 1928 San Felipe Segundo hurricane.[15] Maria weakened significantly while traversing Puerto Rico, but was able to restrengthen to a major hurricane once it emerged over the Atlantic later that afternoon, eventually attaining a secondary peak intensity with winds of 125 mph (201 km/h) on September 22, while north of Hispaniola.[16]

Maria then began fluctuating in intensity for the next few days as the eye periodically appeared and disappeared, while slowly nearing the East Coast of the United States, although southwesterly wind shear gradually weakened the hurricane.[5] By September 25, it passed over cooler sea surface temperatures that had been left behind by Hurricane Jose a week prior, causing its inner core to collapse and the structure of the storm to change significantly.[17] On September 28, a trough that was beginning to emerge off the Northeastern United States swung Maria eastward out to sea, while also weakening to a tropical storm.[5] Periodic bursts of convection near the center managed to maintain Maria's intensity as it accelerated east-northeast across the northern Atlantic Ocean, but interaction with an encroaching frontal zone ultimately resulted in the storm becoming an extratropical cyclone on September 30,[18] which continued east-northeastward, before dissipating on October 2.[5]

Preparations

Upon the initiation of the National Hurricane Center (NHC)'s first advisories for the system that would become Tropical Storm Maria on the morning of September 16, the government of France issued tropical storm watches for the islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe, while St. Lucia issued a tropical storm watch for its citizens, and the government of Barbados issued a similar watch for Dominica.[19] Barbados would later that day declare a tropical storm watch for its citizens and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.[20] The government of Antigua and Barbuda issued Hurricane watches for the islands of Antigua, Barbuda, St. Kitts, Nevis, and Montserrat by the time of the NHC's second advisory which declared Maria a tropical storm.[21][22] The Dominican Republic activated the International Charter on Space and Major Disasters for humanitarian satellite coverage on the 20th.[23]

Puerto Rico

Prior to both Hurricanes Irma and Maria, the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA), already struggling with increasing debt, had seen budget cuts imposed by PROMESA as well as the loss of 30 percent of its work force since 2012. With the median age of PREPA power plants at 44 years, an aging infrastructure across the island made the electric grid more susceptible to damage from storms. Inadequate safety mechanisms also plagued Puerto Rico's electric company, and local newspapers frequently reported on its poor maintenance and outdated control systems.[24]

According to the non-profit environmental advocacy group Natural Resources Defense Council, the island's water system was already in substandard conditions prior to hurricanes Irma and Maria. The NRDC reported that seventy percent of the island had water that did not meet the standards of the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act.[25]

Still recovering from Hurricane Irma two weeks prior, approximately 80,000 remained without power as Maria approached.[26] FEMA's Caribbean Distribution Center warehouse, its only emergency stockpile in the islands, is located on Puerto Rico. By September 15, 2017, 83% of the items there, including 90% of the water and all of the tarps and cots, had been deployed for post-Irma relief, mostly to the U.S. Virgin Islands. Maria arrived before supplies were replenished.[27]

Evacuation orders were issued in Puerto Rico in advance of Maria, and officials announced that 450 shelters would open in the afternoon of September 18.[28] By September 19, 2017, at least 2,000 people in Puerto Rico had sought shelter.[29] Using anonymous aggregate cell phone tracking data provided by Google from users that opted to share location data, researchers reported that travel from Puerto Rico increased 20% the day before the hurricane made landfall. Puerto Rican travelers often chose to go to Orlando, Miami, New York City, and Atlanta. Internally, there was an influx of people into San Juan.[30]

Mainland United States

As Maria approached the coast of North Carolina and threatened to bring tropical storm conditions, a storm surge warning was issued for the coast between Ocracoke Inlet and Cape Hatteras, while a storm surge watch was issued for the Pamlico Sound, the lower Neuse River, and the Alligator River on the morning of September 26. A state of emergency was declared by officials in Dare and Hyde counties, while visitors were ordered to evacuate Hatteras and Ocracoke islands.[31] Ferry service between Ocracoke and Cedar Island was suspended the evening of September 25, and remained suspended on September 26 and 27, due to rough seas, while ferry service between Ocracoke and Hatteras Island was suspended on September 26 and 27.[31][32] The port in Morehead City was closed by the United States Coast Guard on the morning of September 26.[31] Schools in Dare County closed on September 26 and 27, while schools in Carteret and Tyrrell counties, along with Ocracoke Island, dismissed early on September 26, in anticipation of high winds.[31][32] Schools in Currituck County were closed on September 27, due to high winds.[32]

Impact in the Lesser Antilles

| Territory | Fatalities | Missing | Damage (2017 USD) |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominica | 65 | 0 | $1.37 billion | [33][34] |

| Dominican Republic | 5 | 1 | $63 million | [35][36] |

| Guadeloupe (France) | 4 | 0 | $120 million | [37] |

| Haiti | 3 | 0 | — | [38] |

| Martinique (France) | 0 | 0 | $42 million | [39] |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 0 | 0 | $12.8 million | [40] |

| Puerto Rico | 2,975 | 60 | $90 billion | [4][41][42] |

| United States Virgin Islands | 3 | 4 | [43][44] | |

| United States | 4 | 0 | — | [45][46] |

| Totals: | 3,059 | 65 | $91.6 billion |

Windward Islands

The outer rainbands of Maria produced heavy rainfall and strong gusts across the southern Windward Islands.[47] The Hewanorra and George F. L. Charles airports of Saint Lucia respectively recorded 4.33 and 3.1 in (110 and 79 mm) of rain, though even higher quantities fell elsewhere on the island.[48] Scattered rock slides, landslides and uprooted trees caused minor damage and blocked some roads.[49] Several districts experienced localized blackouts due to downed or damaged power lines.[50] The agricultural sector, especially the banana industry, suffered losses from the winds.[49]

Heavy rainfall amounting to 3–5 in (76–127 mm)[51] caused scattered flooding across Barbados; in Christ Church, the flood waters trapped residents from the neighborhood of Goodland in their homes and inundated the business streets of Saint Lawrence Gap.[52][53] Maria stirred up rough seas that flooded coastal sidewalks in Bridgetown and damaged boats as operators had difficulties securing their vessels.[54] High winds triggered an island-wide power outage and downed a coconut tree onto a residence in Saint Joseph.[55][56]

Passing 30 mi (48 km) off the northern shorelines, Maria brought torrential rainfall and strong gusts to Martinique but spared the island of its hurricane-force windfield,[57] which at the time extended 25 mi (40 km) around the eye.[58] The commune of Le Marigot recorded 6.7 inches (170 mm) of rain over a 24-hour period.[59] By September 19, Maria had knocked out power to 70,000 households, about 40% of the population.[60] Water service was cut to 50,000 customers, especially in the communes of Le Morne-Rouge and Gros-Morne.[57][61] Numerous roads and streets, especially along the northern coast, were impassible due to rock slides, fallen trees and toppled power poles.[61][60] Streets in Fort-de-France were inundated.[57] In the seaside commune of Le Carbet, rough seas washed ashore large rocks and demolished some coastal structures,[57][62] while some boats were blown over along the bay of the commune of Schœlcher.[63] Martinique's agricultural sector suffered considerable losses: about 70% of banana crops sustained wind damage, with nearly every tree downed along the northern coast.[64] There were no deaths on the island, although four people were injured in the hurricane—two seriously and two lightly.[61] Agricultural loss were estimated at €35 million (US$42 million).[39]

Dominica

Rainfall ahead of the hurricane caused several landslides in Dominica, as water levels across the island began to rise by the afternoon of September 18.[65] Maria made landfall at 21:15 AST that day (1:15 UTC, September 19) as a Category 5 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 165 mph (266 km/h).[13] These winds, the most extreme to ever impact the island,[66] damaged the roof of practically every home—including the official residence of Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit, who required rescue when his home began to flood.[67] Downing all cellular, radio and internet services, Maria effectively cut Dominica off from the outside world; the situation there remained unclear for a couple of days after the hurricane's passage.[68][69] Skerrit called the devastation "mind boggling" before going offline, and indicated immediate priority was to rescue survivors rather than assess damage.[68] Initial ham radio reports from the capital of Roseau on September 19 indicated "total devastation," with half the city flooded, cars stranded, and stretches of residential area "flattened".[70]

The next morning, the first aerial footage of Dominica elucidated the scope of the destruction.[71] Maria left the mountainous country blanketed in a field of debris: Rows of houses along the entirety of the coastline were rendered uninhabitable, as widespread floods and landslides littered neighborhoods with the structural remnants.[71][72] The hurricane also inflicted extensive damage to roads and public buildings, such as schools, stores and churches,[72] and affected all of Dominica's 73,000 residents in some form or way.[73] The air control towers and terminal buildings of the Canefield and Douglas Charles airports were severely damaged, although the runways remained relatively intact and open to emergency landings.[73] The disaster affected all of the island's 53 health facilities, including the badly damaged primary hospital, compromising the safety of many patients.[71][74]

The infrastructure of Roseau was left in ruins; practically every power pole and line was downed, and the main road was reduced to fragments of flooded asphalt. The winds stripped the public library of its roof panels and demolished all but one wall of the Baptist church.[75] To the south of Roseau, riverside flooding and numerous landslides impacted the town of Pointe Michel, destroying about 80% of its structures and causing most of the deaths in the country.[76][77] Outside the capital area, the worst of the destruction was concentrated around the east coast and rural areas, where collapsed roads and bridges isolated many villages.[73] The port and fishing town of Marigot, Saint Andrew Parish, was 80% damaged.[78] Settlements in Saint David Parish, such as Castle Bruce, Good Hope and Grand Fond, had been practically eradicated; many homes hung off cliffs or decoupled from their foundations. In Rosalie, rushing waters gushed over the village's bridge and damaged facilities in its bay area. Throughout Saint Patrick Parish, the extreme winds ripped through roofs and scorched the vegetation. Buildings in Grand Bay, the parish's main settlement, experienced total roof failure or were otherwise structurally compromised. Many houses in La Plaine caved in or slid into rivers, and its single bridge was broken.[79]

Overall, the hurricane damaged the roofs of as much as 98% of the island's buildings,[73] including those serving as shelters;[71] half of the houses had their frames destroyed.[73] Its ferocious winds defoliated nearly all vegetation, splintering or uprooting thousands of trees and decimating the island's lush rainforests.[80] The agricultural sector, a vital source of income for the country, was completely wiped out: 100% of banana and tuber plantations was lost, as well as vast amounts of livestock and farm equipment.[73] In Maria's wake, Dominica's population suffered from an island-wide water shortage due to uprooted pipes. The Assessment Capacities Project estimates that the hurricane has caused EC$3.69 billion (US$1.37 billion) in losses across the island, which is equal to 226 percent of its 2016 GDP.[33] As of April 12, 2019, a total of 65 fatalities have been confirmed across the island, including 34 who are missing and presumed to be dead.[34]

Post-hurricane relief aid that was brought to Dominica from regional partners and aiding countries additionally brought several non-native species that became established and which local stakeholders are still trying to remove in 2022.[81]

Guadeloupe

Blustery conditions spread over Guadeloupe as Maria tracked to the south of the archipelago, which endured hours of unabating hurricane-force winds.[82] The strongest winds blew along the southern coastlines of Basse-Terre Island: Gourbeyre observed a peak wind speed of 101 mph (163 km/h), while winds up north in nearby Baillif reached 92 mph (148 km/h).[83] Along those regions, the hurricane kicked up extremely rough seas with 20 ft (6.1 m) waves.[84] The combination of rough seas and winds was responsible for widespread structural damage and flooding throughout the archipelago, especially from Pointe-à-Pitre, along Grand-Terre Island's southwestern coast, to Petit-Bourg and the southern coasts on Basse-Terre Island.[85] Aside from wind-related effects, rainfall from Maria was also significant. In just a day, the hurricane dropped nearly a month's worth of rainfall at some important locations: Pointe-à-Pitre recorded a 24-hour total of 7.5 inches (190 mm), while the capital of Basse-Terre measured 6.4 in (160 mm).[59] Even greater quantities fell at higher elevations of Basse Terre Island, with a maximum total of 18.07 in (459 mm) measured at the mountainous locality of Matouba, Saint-Claude.[83]

Throughout the archipelago, the hurricane left 40% of the population (80,000 households) without power and 25% of landline users without service.[86] The islands of Marie-Galante, La Désirade and especially Les Saintes bore the brunt of the winds, which caused heavy damage to structures and nature alike and cut the islands off from their surroundings for several days.[85][86] Homes on Terre-de-Haut Island of Les Saintes were flooded or lost their roofs.[87] On the mainland, sections of Pointe-à-Pitre stood under more than 3.3 feet (1.0 m) of water, and the city's hospital sustained significant damage.[61] The Basse-Terre region suffered severe damage to nearly 100% of its banana crops, comprising a total area of more than 5,000 acres (2,000 hectares); farmers described the destruction to their plantations as "complete annihilation".[64] Beyond their impact on farmland, the strong winds ravaged much of the island's vegetation: fallen trees and branches covered practically every major road and were responsible for one death.[86] Another person was killed upon being swept out to sea.[85] Two people disappeared at sea after their vessel capsized offshore La Désirade, east of mainland Grande-Terre,[86] and they are presumed to be dead afterwards.[37] Damage from Maria across Guadeloupe amounted to at least €100 million (US$120 million).[88]

U.S. Virgin Islands

Two weeks after Hurricane Irma hit St. Thomas and St. John as a Category 5 hurricane, Hurricane Maria's weaker outer eyewall was reported by the National Hurricane Center (NHC) to have crossed Saint Croix, while the hurricane was at Category 5 intensity. Sustained winds at the Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge on St. Croix reached 99 to 104 mph (159 to 167 km/h) and gusted to 137 mph (220 km/h).[89] Damage was most extensive in the town of Frederiksted,[citation needed] on the west end of St. Croix, as well as along the southern shoreline, leaving 3 people dead. Weather stations on St. Croix recorded between 10 and 20 inches (250 and 510 mm) of rain from the hurricane, and estimates for St. John and St. Thomas were somewhat less.[90]

The hurricane killed two people, both in their homes: one person drowned and another was trapped by a mudslide.[43] A third person had a fatal heart attack during the hurricane.[44] The hurricane caused severe damage to St. Croix. It took almost a year for power to be restored to most residents. U.S. President Donald Trump declared a major disaster in the U.S. Virgin Islands one day after Maria hit. The move freed up federal funding for people on the island of St. Croix. After both hurricanes, the office of V.I. congresswoman Stacey Plaskett stated that 90% of buildings in the Virgin Islands were damaged or destroyed and 13,000 of those buildings had lost their roofs.[91] The Governor Juan F. Luis Hospital & Medical Center on St. Croix suffered roof damage and flooding, but remained operational.[92]

Impact in the Greater Antilles and the United States

Puerto Rico

The storm made landfall on Puerto Rico on Wednesday, September 20, near the Yabucoa municipality at 10:15 UTC (6:15 a.m. local time) as a high-end Category 4 hurricane with winds of 155 mph (249 km/h).[93] A sustained wind of 64 mph (103 km/h) with a gust to 113 mph (182 km/h) was reported in San Juan, immediately prior to the hurricane making landfall on the island. After landfall, wind gusts of 109 mph (175 km/h) were reported at Yabucoa Harbor and 118 mph (190 km/h) at Camp Santiago.[94] A minimum barometric pressure reading of 926.6 mbar (27.36 inHg) was reported in Yabucoa.[5] In addition, heavy rainfall occurred throughout the territory, peaking at 37.9 inches (960 mm) in Caguas.[95] The eyewall replacement cycle that caused María to weaken to Category 4 strength also caused the eye to triple in size as the diameter expanded 9–28 nmi (10–32 mi) prior to landfall. This change in size caused the area exposed to high-intensity winds on the island to be far greater.[5] Widespread flooding affected San Juan, waist-deep in some areas, and numerous structures lost their roof.[93] The coastal La Perla neighborhood of San Juan was largely destroyed.[96] Cataño saw extensive damage, with the Juana Matos neighborhood estimated to be 80-percent destroyed.[97] The primary airport in San Juan, the Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport, was slated to reopen on September 22.[98]

Extensive damage occurred to hundreds of thousands of buildings throughout Puerto Rico due to high winds, heavy rainfall, storm surge, wave action and landslides. Ricardo Rosselló estimated that over 300,000 homes had been destroyed and many more damaged across the commonwealth. Other estimates included 166,000 residential buildings damaged or destroyed and 472,000 housing units having received major damage or having been destroyed.[99]

Storm surge and flash flooding—stemming from flood gate releases at La Plata Lake Dam—converged on the town of Toa Baja, trapping thousands of residents. Survivors indicate that flood waters rose at least 6 ft (1.8 m) in 30 minutes, with flood waters reaching a depth of 15 feet (4.6 m) in some areas. More than 2,000 people were rescued once military relief reached the town 24 hours after the storm. At least eight people died from the flooding, while many were unaccounted for.[100]

On September 24, Puerto Rico's Governor Ricardo Rosselló estimated that the damage from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico was probably over the $8 billion damage figure from Hurricane Georges.[101] Approximately 80 percent of the territory's agriculture was lost due to the hurricane, with agricultural losses estimated at $780 million.[102]

The hurricane completely destroyed the island's power grid, leaving all 3.4 million residents without electricity.[97][103][104] Governor Rosselló stated that it could take months to restore power in some locations,[105] with San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz estimating that some areas would remain without power for four to six months.[106] Communication networks were crippled across the island. Ninety-five percent of cell networks were down, with 48 of the island's 78 counties networks being completely inoperable.[103] Eighty-five percent of above-ground phone and internet cables were knocked out.[107] Only twelve radio stations, namely WAPA 680 AM, WPAB 550 AM & WISO 1260 AM of Ponce, WKJB 710 AM, WPRA 990 AM & WTIL 1300 AM of Mayaguez, WMIA 1070 AM of Arecibo, WVOZ 1580 AM of Morovis, WXRF 1590 AM of Guayama, WALO 1240 AM of Humacao and WOIZ 1130 AM of Guayanilla, remained on the air during the storm.[103]

Hurricane Maria caused landslides across the island and in some municipalities there were more than 25 landslides per square mile.[108][109]

The NEXRAD Doppler weather radar of Puerto Rico was blown away. The radome which covers the radar antenna, and which was designed to withstand winds of more than 130 mph, was destroyed while the antenna of 30 feet in diameter was blown from the pedestal, the latter remaining intact. The radar is 2,800 ft (850 m) above sea level, and the anemometer at the site measured winds of about 145 mph (233 km/h) before communications broke, which means winds at that height were likely 20 percent higher than what was seen at sea level. The radar was rebuilt and finally brought back online 9 months later.[110][111]

The nearby island of Vieques suffered similarly extensive damage. Communications were largely lost across the island. Widespread property destruction took place with many structures leveled.[112] The remaining structures on the island of Culebra were extremely vulnerable to Maria's powerful winds after having recently experienced major damage due to Hurricane Irma, causing the complete destruction of many wooden houses, along with blown off roofs and sunken boats.[5]

The former survey ship Ferrel, carrying a family of four, issued a distress signal while battling 20-foot seas (6.1 m) and 115 mph winds (185 km/h) on September 20.[113] Communications with the vessel were lost near Vieques on September 20. The United States Coast Guard, United States Navy, and British Royal Navy conducted search-and-rescue operations using an HC-130 aircraft, a fast response cutter, USS Kearsarge, RFA Mounts Bay and Navy helicopters.[114] On September 21, the mother and her two children were rescued while the father drowned inside the capsized vessel.[113]

Maria's Category 4 winds broke a 96-foot (29 m) line feed antenna of the Arecibo Observatory, causing it to fall 500 feet (150 m) and puncturing the dish below, greatly reducing its ability to function until repairs could be made.[115][116]

Hurricane Maria greatly affected Puerto Rico's agriculture. Coffee was the worst affected crop, with 18 million coffee trees destroyed, which will require about five to ten years to bring back at least 15% of the coffee production of the island.[117]

The Whitney Museum of American Art documented Hurricane Maria experiences in Puerto Rico and its aftermath in an art exhibition November 23, 2022 – April 23, 2023: "no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria."[118]

Hispaniola

Torrential rains and strong winds impacted the Dominican Republic as Maria tracked northeast of the country. Assessments on September 22 indicated that 110 homes were destroyed, 570 were damaged, and 3,723 were affected by flooding. Approximately 60,000 people lost power in northern areas of the country. Flooding and landslides rendered many roads impassable, cutting off 38 communities.[119] Five people, all of them males, were killed in the Dominican Republic: four of them were of Haitian origin, killed when they were swept away by floodwaters; the fifth person was a Dominican man who died in a landslide.[35] Infrastructural damage amounted to RD$3 billion (US$63 million).[36]

Hurricane Maria's center passed 250 km (160 mi) from Haiti's northern coast, but triggered a large amount of rain and some flooding in Haiti. Three deaths were reported: a 45-year-old man died in the commune of Limbe, in the department of the North, while attempting to cross a flooded river. Two other people, a woman and a man, died in Cornillon, a small town 40 km (25 mi) east of the capital Port-au-Prince, according to the authorities.[38]

Mainland United States

Maria brushed the Outer Banks of North Carolina on September 26, as the center of the storm passed by offshore and brought tropical storm conditions to the area, along with a storm surge, large waves, and rip currents to the coast. The storm knocked out power to 800 Duke Energy Progress customers in the Havelock area.[31] Dominion North Carolina Power and Cape Hatteras Electric Cooperative experienced scattered power outages. Winds of 23 mph (37 km/h) and gusts of 41 mph (66 km/h) were reported at Dare County Regional Airport at Manteo on September 27, while winds of 40 mph (64 km/h) were reported in Duck, North Carolina.[32] Maria caused beach erosion at the ferry terminal at the north end of Ocracoke Island that washed out a portion of the paved lanes where vehicles wait to board the ferry. By the morning of September 26, the storm flooded North Carolina Highway 12 along the coast.[31] Rip currents from Maria caused three swimmers to drown and several others to be rescued at the Jersey Shore on the weekend of September 23–24.[120] A fourth drowning death occurred in Fernandina Beach, Florida.[46]

Aftermath

Dominica

People are trying to be strong in Dominica, like everything is fine, but it's not. Everywhere needs rebuilding but there is no money to rebuild things with. OK, so we have some food and water—but how long for? Everything else is gone.

In the wake of the hurricane, more than 85% of the island's houses were damaged, of which more than 25% were completely destroyed, leaving more than 50,000 of the island's 73,000 residents to be displaced.[122] Following the destruction of thousands of homes, most supermarkets and the water supply system, many of Dominica's residents were in dire need of food, water and shelter for days.[72] With no access to electricity or running water, and with sewage systems destroyed, fears of widespread diarrhea and dysentery arose. The island's agriculture, a vital source of income for many, was obliterated as most trees were flattened. Meanwhile, the driving force of the economy—tourism—was expected to be scarce in the months that followed Maria. Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit characterized the devastation wrought by Irma and Maria as a sign of climate change and the threat it poses to the survival of his country, stating, "To deny climate change ... is to deny a truth we have just lived."[122] Many islanders suffered respiratory problems as a result of excessive dust borne out of the debris. Light rainfall in the weeks following Maria alleviated this problem, although it also slowed recovery efforts, particularly rebuilding damaged rooftops.[citation needed]

Through the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility, Dominica received approximately US$19.2 million in emergency funds.[123] USS Wasp, previously deployed to Saint Martin to assist in relief efforts after Hurricane Irma, arrived in Dominica on September 22. The vessel carried two Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk helicopters to assist in distribution of relief supplies in hard-to-reach areas.[124] At the United Nations General Assembly on September 23, Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit called the situation in Dominica an "international humanitarian emergency".[125] The Royal Canadian Navy vessel HMCS St. John's was dispatched to Dominica[126] at the request of Dominican Prime Minister Skerrit.[127]

The prime minister urged churches to encourage their membership to provide housing for senior citizens and disabled, many of whom remained in damaged structures despite tarpaulin donations from Venezuela, Israel, Cuba, Jamaica, and other countries. As schools began to reopen on October 16, the United Nations Children's Fund reported that the entire child population of Dominica—23,000 children—remained vulnerable due to restricted access to clean drinking water.[citation needed] Efforts to rebuild homes and buildings across the island were steady, albeit slowed due to lack of funds. Almost two years after Maria, shelters remained operational as many homes still lacked significant roofing.[128]

Puerto Rico

Initial recovery

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Damage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 Katrina | 2005 | $125 billion |

| 4 Harvey | 2017 | ||

| 3 | 4 Ian | 2022 | $112 billion |

| 4 | 4 Maria | 2017 | $90 billion |

| 5 | 4 Helene | 2024 | $78.7 billion |

| 6 | 4 Ida | 2021 | $75 billion |

| 7 | ET Sandy | 2012 | $65 billion |

| 8 | 4 Irma | 2017 | $52.1 billion |

| 9 | 3 Milton | 2024 | $34.3 billion |

| 10 | 2 Ike | 2008 | $30 billion |

There's a humanitarian emergency here in Puerto Rico. ... This is an event without precedent.

The power grid was effectively destroyed by the hurricane, leaving millions without electricity.[132] Governor Ricardo Rosselló estimated that Maria caused at least US$90 billion in damage[133][134] and in 2018 the US National Hurricane Center updated its list of costliest hurricanes to include that figure.[135]

On September 26, 2017, 95% of the island was without power, less than half the population had tap water, and 95% of the island had no cell phone service.[136] On October 6, a little more than two weeks after the hurricane, 89% still had no power, 44% had no water service, and 58% had no cell service.[137]

Two weeks after the hurricane, international relief organization Oxfam chose to intervene for the first time on American soil since Hurricane Katrina in 2005.[138]

One month after the hurricane, 88% of the island was without power (about 3 million people), 29% lacked tap water (about 1 million people), and 40% of the island had no cell service. A month after the hurricane, most hospitals were open,[139] but most were on backup generators that provide limited power. Angelique Sina's non-profit organization, Friends of Puerto Rico, had supplied generators for hospitals in two cities, by November 2017.[140] About half of sewage treatment plants on the island were still not functioning. FEMA reported 60,000 homes needed roofing help, and had distributed 38,000 roofing tarps.[141] The island's highways and bridges remained heavily damaged nearly a month later. Only 392 miles of Puerto Rico's 5,073 miles of road were open. Some towns continued to be isolated and delivery of relief supplies including food and water were hampered—helicopters were the only alternative.[142]

By October 1, 2017, there were ongoing fuel shortage and distribution problems, with 720 of 1,100 gas stations open.[143] In November the New York Times reported there had been a spike in suicides in the storm's aftermath as residents struggled with life without electricity. The rate of suicides doubled over the pre-Maria rate.[144]

The Guajataca Dam was structurally damaged, and on September 22, the National Weather Service issued a flash flood emergency for parts of the area in response.[145] Tens of thousands of people were ordered to evacuate the area, with about 70,000 thought to be at risk.[146]

The entirety of Puerto Rico was declared a Federal Disaster Zone shortly after the hurricane.[131] The Federal Emergency Management Agency planned to open an air bridge with three to four aircraft carrying essential supplies to the island daily starting on September 22.[103] Beyond flights involving the relief effort, limited commercial traffic resumed at Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport on September 22 under primitive conditions. A dozen commercial flights operated daily, as of September 26, 2017.[147] By October 3, there were 39 commercial flights per day from all Puerto Rican airports, about a quarter of the normal number.[148] The next day, airports were reported to be operating at normal capacity.[149] The territory's government contracted 56 small companies to assist in restoring power.[131] Eight FEMA Urban Search & Rescue (US&R) teams were deployed to assist in rescue efforts.[150]

On September 24, the amphibious assault ship USS Kearsarge and the dock landing ship USS Oak Hill under Rear Admiral Jeffrey W. Hughes along with the 2,400 marines of the 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit arrived to assist in relief efforts.[151][152][153][154] By September 24, there were thirteen United States Coast Guard ships deployed around Puerto Rico assisting in the relief and restoration efforts: the National Security Cutter USCGC James; the medium endurance cutters USCGC Diligence, USCGC Forward, USCGC Venturous, and USCGC Valiant; the fast response cutters USCGC Donald Horsley, USCGC Heriberto Hernandez, USCGC Joseph Napier, USCGC Richard Dixon, and USCGC Winslow W. Griesser; the coastal patrol boat USCGC Yellowfin; and the seagoing buoy tenders USCGC Cypress and USCGC Elm.[155] Federal aid arrived on September 25 with the reopening of major ports. Eleven cargo vessels collectively carrying 1.3 million liters of water, 23,000 cots, and dozens of generators arrived.[156] Full operations at the ports of Guayanilla, Salinas, and Tallaboa resumed on September 25, while the ports of San Juan, Fajardo, Culebra, Guayama, and Vieques had limited operations.[150] The United States Air Force Air Mobility Command has dedicated eight C-17 Globemaster aircraft to deliver relief supplies.[150] The Air Force assisted the Federal Aviation Administration with air traffic control repairs to increase throughput capacity.[150] The logistics support ship SS Wright (T-AVB-3) was mobilized on September 22 to support relief operations delivering 1.3 million MREs and one million liters of fresh water.[157][158]

The United States Transportation Command moved additional personnel and eight U.S. Army UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters from Fort Campbell, Kentucky to Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport to increase distribution capacity.[150] The United States Army Corps of Engineers deployed 670 personnel engaged in assessing and restoring the power grid; by September 25, 83 generators were installed and an additional 186 generators were en route.[150] By September 26, 2017, agencies of the U.S. government had delivered four million meals, six million liters of water, 70,000 tarps and 15,000 rolls of roof sheeting.[159] National Guard troops were activated and deployed to Puerto Rico from Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, New York, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin.[160]

On September 29, the hospital ship USNS Comfort left port at Norfolk, Virginia to help victims of Hurricanes Irma and Maria, and arrived in San Juan on October 3. A couple of days later, Comfort departed on an around the island tour to assist, remaining a dozen miles off shore.[161] Patients were brought to the ship by helicopter or boat tender after being referred by Puerto Rico's Department of Health. However, most of the 250 bed floating state-of-the-art hospital went unused despite overburdened island clinics and hospitals because there were few referrals.[162][163] Governor Rosselló explained on or about October 17 that "The disconnect or the apparent disconnect was in the communications flow" and added "I asked for a complete revision of that so that we can now start sending more patients over there."[163] After remaining offshore for three weeks, the Comfort docked in San Juan on October 27, briefly departing only once to restock at sea from a naval resupply ship.[161] By November 8, 2017, Comfort's staff had treated 1,476 patients, including 147 surgeries and two births.[164]

On September 27, the Pentagon reopened two major airfields on Puerto Rico and started sending aircraft, specialized units, and a hospital ship to assist in the relief effort; Brigadier General Richard C. Kim, the deputy commanding general of United States Army North, was responsible for coordinating operations between the military, FEMA and other government agencies, and the private sector.[165] Massive amounts of water, food, and fuel either had been delivered to ports in Puerto Rico or were held up at ports in the mainland United States because there was a lack of truck drivers to move the goods into the interior; the lack of communication networks hindered the effort as only 20% of drivers reported to work.[166] By September 28, the Port of San Juan had been able to dispatch only 4% of deliveries received and had very little room to accept additional shipments.[167] By September 28, 44 percent of the population remained without drinking water and the U.S. military was shifting from "a short term, sea-based response to a predominantly land-based effort designed to provide robust, longer-term support" with fuel delivery a top priority.[168] A joint Army National Guard and Marine expeditionary unit (MEU) team established an Installation Staging Base at the former Roosevelt Roads Naval Station; they transported via helicopter Department of Health and Human Services assessment teams to hospitals across Puerto Rico to determine medical requirements.[168] On September 29, the amphibious assault ship USS Wasp which had been providing relief activities to the island of Dominica was diverted to Puerto Rico.[169] By September 30, FEMA official Alejandro de la Campa stated that 5% of electricity, 33% of the telecommunications infrastructure, and 50% of water services had been restored to the island.[170]

On September 28, 2017, Lieutenant General Jeffrey S. Buchanan was dispatched to Puerto Rico to lead all military hurricane relief efforts there and to see how the military could be more effective in the recovery effort, particularly in dealing with the thousands of containers of supplies that were stuck in port because of "red tape, lack of drivers, and a crippling power outage".[172][173] On September 29 he stated that there were not enough troops and equipment in place but more would be arriving soon.[174]

With centralized fossil-fuel-based power plants and grid infrastructure expected to be out of commission for weeks to months, some renewable energy projects were in the works, including the shipment of hundreds of Tesla Powerwall battery systems to be integrated with solar PV systems[175] and Sonnen solar microgrid projects at 15 emergency community centers; the first were expected to be completed in October.[176] In addition, other solar companies jumped into help, including Sunnova and New Start Solar. A charity called Light Up Puerto Rico raised money to both purchase and deliver solar products, including solar panels, on Oct. 19.[177] The idea would be to supplement the existing electrical grid with power from solar and wind farms. A complete replacement of fossil fuel infrastructure is unlikely as solar and wind are too intermittent and are also vulnerable to another hurricane.[178][179] Four of the five large solar farms on Puerto Rico were damaged and many of the wind turbines suffered damaged blades.[180][181]

Many TV and movie stars donated money to hurricane relief organizations to help the victims of Harvey and Maria. Prominently, Jennifer Aniston pledged a million U.S. dollars, dividing the amount equally between the Red Cross and the Ricky Martin Foundation for Puerto Rico. Martin's foundation had raised over three million dollars by October 13, 2017.[182]

On October 9, 2017, the United States Postal Service stated that 99 of its 128 offices were delivering packages and mail to residents, albeit some were working out of tents[183] and their offices had no power for one week after the hurricane. Care packages were coming in to Puerto Rico from all over and USPS hired temporary workers and had workers delivering packages 7 days a week, to help with the brunt.[184]

On October 10, 2017, Carnival Cruise Lines announced that it would resume departures of cruises from San Juan on October 15, 2017.[185] On October 13, both CNN and The Guardian reported that Puerto Ricans were drinking water that was being pumped from a well at an EPA Superfund site;[186][187] the water was later determined to be safe to drink.[188]

On October 13, the Trump administration requested $4.9 billion to fund a loan program that Puerto Rico could use to address basic functions and infrastructure needs.[190] On October 20, only 18.5% of the island had electricity, 49.1% of cell towers were working, and 69.5% of customers had running water, with the slowest restoration in the north.[191] Ports and commercial flights were back to normal operations, but 7.6% of USPS locations, 11.5% of supermarkets, and 21.4% of gas stations were still closed.[191] 4,246 people were still living in emergency shelters, and tourism was down by half.[191] On November 5, more than 100,000 people had left Puerto Rico for the mainland.[192] A December 17 report indicated that 600 people remained in shelters while 130,000 had left the island to go to the mainland.[193]

Three months after the hurricane, 45% of Puerto Ricans still had no power, over 1.5 million people.[194] 14% of Puerto Rico had no tap water; cell service was returning with over 90% of service restored and 86% of cell towers functioning.[138]

Elaine Duke, the acting Secretary of Homeland Security at the time, recalled years later that President Trump suggested "selling" Puerto Rico in the aftermath of the hurricane. "Can we outsource the electricity? Can we sell the island? You know, or divest of that asset?" she remembered him saying. She said the topic was never mentioned again beyond that comment.[195] Former DHS Chief of Staff Miles Taylor said that Trump asked if they could swap Puerto Rico for Greenland, because ""Puerto Rico was dirty and the people were poor."[196]

Recovery between 2018 and 2019

Puerto Rico is a major manufacturer of medical devices and pharmaceuticals, which represent 30% of its economy.[197] These factories shut down or greatly reduced production because of the hurricane, and were slowly recovering since.[198] This caused a months long shortage in medical supplies in the United States, especially of IV bags.[199][200] Small IV bags often come pre-filled with saline or common drugs in solution, and have forced health care providers to scramble behind the scenes for alternative methods of drug delivery.[198][199] In January 2018, when the shortage was projected to ease, flu season hit and led to a spike in patients.[199]

By the end of January 2018, approximately 450,000 customers remained without power island-wide.[201] On February 11, an explosion and fire damaged a power substation in Monacillo,[202] causing a large blackout in northern parts of the island, including Caguas, Carolina, Guaynabo, Juncos, San Juan, and Trujillo Alto. Cascading outages affected areas powered by substations in Villa Betina and Quebrada Negrito. Approximately 400 megawatts of electricity production was lost.[201] On March 1, 2018, a second major blackout occurred when a transmission line failed and caused two power stations to shut down;[203] more than 970,000 people lost electricity.[204] Excluding those affected by the second blackout, more than 200,000 people remained without power following Maria on March 2, 2018.[203] Another large-scale blackout occurred on April 12 from a line failure.[205] Less than a week later on April 18, another blackout affected all of Puerto Rico. Rapid transit line passengers required help to disembark stalled trains.[206][dubious – discuss]

Power was not restored to all customers until August 2018.[207]

FEMA was a major supplier of relief in the form of bereavement, food, and other emergency supplies, as well as rebuilding some homes. FEMA's relief efforts in Puerto Rico post-Maria engaged a smaller work force and budget than the agency's efforts in Texas and Florida, in the wake of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, respectively. FEMA does not rebuild homes to which the owner has no title, which has presented a major obstacle for many Puerto Ricans, who may have erected structures on family plots without procuring legal paperwork beforehand.[208] Compounding the problem in rebuilding the housing infrastructure is the fact that only about 50% of houses in Puerto Rico were covered by insurance policies that protect against wind damage, meaning that homeowners were reliant on their own money, FEMA, or other charities rather than insurance proceeds for rebuilding.[209] Although banks require that people with mortgages have homeowner's insurance, Puerto Rico has a low mortgage penetration rate with only 500,000 active mortgages in a population of 3 million as many homes are fully owned by families and passed to the next generation.[209] In addition, 10% of mortgage holders in Puerto Rico were delinquent at the time (compared to 5.8% on the mainland), an indication of the fragile state of the local economy.[209]

As a consequence of the hurricane, a population drop of approximately 14% was forecasted, due to an exodus to the mainland United States, according to a research study conducted by the Center for Puerto Rican Studies of Hunter College.[210] In preparation for the 2018 hurricane season, FEMA drastically increased its stockpiles on the island, including 35 times more bottled water, 43 times more tarps, and 16 times more meals as the previous year.[211] FEMA has added three new warehouses on Puerto Rico and pre-positioned emergency power generators at hospitals and water pump stations. The territorial government added satellite and radio equipment at hospitals, to prevent a communications blackout in the event the land and cell phone networks fail again.[212] In addition to FEMA, Direct Relief provided important medical supplies to those affected including insulin and vaccines.[213] A year later, repairs to homes were not completed, schools were shuttered, and residents were suffering from depression.[214]

Funding delays and continued recovery

Governor Rosselló submitted a vague request to Congress for $94.4 billion in disaster recovery funds, including $15 billion for health care, $17.7 for the power grid, $8.4 billion for schools,[215] and $46 billion for Community Development Block Grants.[216] The territorial government estimated it needed $132 billion from 2018 to 2028 to repair damaged infrastructure.[217]

As of November 2021, in addition to increasing emergency stockpiles in the territory, the federal government had allocated for Hurricane Maria recovery:[218]

- $28.9 billion in government-to-government assistance:

- $725 million: debris removal

- $4.6 billion: emergency protective measures

- $23.6 billion: permanent public works

- $168 million: Hazard Mitigation Grant Program

- $20 billion: Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery Program from United States Department of Housing and Urban Development

- $9.5 billion: power grid reconstruction

- $1.5 billion: individual assistance from FEMA

The Government Accountability Office reported that as of August 2022, the government of Puerto Rico had expended only $5.3 billion of the government-to-government assistance, mostly on debris removal and emergency measures.[217][219] $407 million had been spent on permanent repairs.[220] GAO cited lack of local familiarity with disaster programs, problems procuring labor and supplies, inflation, and difficulty reaching agreement about project scopes.[217] As of September 2022, only $40.3 million out of a $13.2 billion FEMA budget had been spent on utility repairs.[220] FEMA attempted to bypass Puerto Rico's lack of capital by offering to disburse grant money up front rather than reimbursing already-spent funds, but the newness of this system caused delays.[220]

About 60% of households that applied for FEMA assistance were rejected, primarily for lack of proof of ownership.[221] Different legal and inheritance customs in Puerto Rico often result in there being no title deed to a property. Further, there have been accusations that FEMA policies have been applied unfairly.[222] January 2019 has also seen a $600 million cut in food aid to Puerto Rico by the Trump Administration.[223][224]'

In 2019 and 2020, the Trump Administration added layers of federal review for HUD CDBG money not required for U.S. states, citing the possibility of corruption and mismanagement and delaying the release of funds.[225] Access to federal programs was further delayed by the 2018–2019 United States federal government shutdown.[226] The Washington Post reported that President Trump, contrary to the law he had signed, wanted to stop all aid to Puerto Rico and redirect it to Texas and Florida, and that (despite her citation of personal reasons) HUD Deputy Secretary Pam Patenaude resigned in part because of frustration over distribution efforts.[227]

Slow arrival of relief funding became an issue in the 2020 United States presidential election.[228] After his victory, the administration of President Joe Biden removed the additional restrictions on billions of dollars of HUD CDBG funds.[225][228]

In January 2021, people affected by the 2019–20 Puerto Rico earthquakes broke into a warehouse in Ponce, discovering aid supplies that should have been used in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria.[229]

As of January 2023, the roofs of residences damaged by Hurricanes Maria, Irma, and even Georges (in 1998) were still being repaired.[230]

Estimating fatalities

| Deadliest United States hurricanes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Fatalities |

| 1 | 4 "Galveston" | 1900 | 8,000–12,000 |

| 2 | 4 "San Ciriaco" | 1899 | 3,400 |

| 3 | 4 Maria | 2017 | 2,982 |

| 4 | 5 "Okeechobee" | 1928 | 2,823 |

| 5 | 4 "Cheniere Caminada" | 1893 | 2,000 |

| 6 | 3 Katrina | 2005 | 1,392 |

| 7 | 3 "Sea Islands" | 1893 | 1,000–2,000 |

| 8 | 3 "Indianola" | 1875 | 771 |

| 9 | 4 "Florida Keys" | 1919 | 745 |

| 10 | 2 "Georgia" | 1881 | 700 |

| Reference: NOAA, GWU[231][232][nb 1] | |||

The deaths of 64 people were initially directly attributed to the hurricane by the government of Puerto Rico.[233]

In the immediate months following Maria, the initial death toll relayed from the Government of Puerto Rico came into question by media outlets, politicians, and investigative journalists. Scores of people who survived the hurricane's initial onslaught later died from complications in its aftermath. Catastrophic damage to infrastructure and communication hampered efforts to accurately document the total loss of life.

Investigations into the hurricane's aftermath suggested a wide variety of possible death tolls. On October 11, 2017, Vox reported 81 deaths directly or indirectly related to the hurricane, with another 450 deaths awaiting investigation. Furthermore, they indicated 69 people were missing.[234] Official statistics showed increases of about 20% and 27% in overall fatalities in Puerto Rico during September 2017, compared to 2016 and 2015, followed by a decrease of about 10% in October 2017 compared to the previous two Octobers.[235][236] There were 238 more reported deaths in September and October 2017 than during the same months in 2016, and 336 more compared to September and October 2015.[236] A two-week investigation in November 2017 by CNN of 112 funeral homes—approximately half of the island—found 499 deaths that were said to be hurricane-related between September 20 and October 19.[237] Two scientists, Alexis Santos and Jeffrey Howard, estimated the death toll in Puerto Rico to be 1,085 by the end of November 2017. They used average monthly deaths and the spike in fatalities following the hurricane. The value accounted for only reported deaths, and with limitations to communication, the actual toll could have been even higher.[238] Using a similar method, The New York Times indicated an increase of 1,052 fatalities in the 42 days following Maria compared to previous years. Significant spikes in causes of deaths compared to the two preceding Septembers included sepsis (+47%), pneumonia (+45%), emphysema (+43%), diabetes (+31%), and Alzheimer's and Parkinson's (+23%).[239] Robert Anderson at the National Center for Health Statistics conveyed the increase in monthly fatalities was statistically significant and likely driven in some capacity by Hurricane Maria.[239] A Harvard study found an estimated 15 excess deaths in the four months after the hurricane in interviews with 3,299 households, resulting in an estimated 793 to 8,498 excess deaths (with a 95% confidence interval).[240][241][242]

On December 18, 2017, Governor Rosselló ordered a recount and a new analysis of the official death toll.[243] In February 2018, the task of reviewing the death toll was given to The George Washington University – Milken Institute School of Public Health with some assistance from the University of Puerto Rico at the request of researchers from George Washington University.[244] In response to three lawsuits, including one from CNN and Puerto Rico's Center for Investigative Journalism, the Government of Puerto Rico released updated death statistics for the months following Hurricane Maria. Compared to the average deaths in September to December 2013 – 2016, September to December 2017 had 1,427 excess deaths; however, it is unknown how many of these deaths are attributable to the hurricane. The government acknowledged the death toll was greater than 64, but awaited the results of the government commissioned study to determine the true death toll.[245][246]

Donald J. Trump @realDonaldTrump3,000 people did not die in the two hurricanes that hit Puerto Rico. When I left the Island, AFTER the storm had hit, they had anywhere from 6 to 18 deaths. As time went by it did not go up by much. Then, a long time later, they started to report really large numbers, like 3,000 ...

September 13, 2018[247]

In late August 2018, almost a year after the hurricane, the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University published their results. They estimated 2,658–3,290 additional people died in the six months after the hurricane over the expected background rate, after accounting for emigration from the island.[248] As result, the official death toll was updated from the initial 64 to an estimated 2,975 by the Governor of Puerto Rico.[233][214]

In September 2018, President Trump disputed the revised death toll. Writing on Twitter, Trump claimed that "3000 people did not die in the two hurricanes that hit Puerto Rico", but that the Democrats had inflated the official death toll to "make me look as bad as possible". Trump provided no evidence to support his claims.[249] The response was met with immediate criticism, including from Mayor of San Juan Carmen Yulín Cruz and Florida Congresswoman and fellow Republican Ileana Ros-Lehtinen.[250]

U.S. Virgin Islands

By September 25, 2017, the U.S. Coast Guard reported that the ports of Crown Bay, East Gregerie Channel, West Gregerie Channel, and Redhook Bay on Saint Thomas; the ports of Krause Lagoon, Limetree Bay, and Frederiksted on Saint Croix, and the port of Cruz Bay on Saint John were open with restrictions.[150] On September 25, 11 flights arrived with 200,000 meals, 144,000 liters of water, and tarps.[150] Troops were activated and deployed to the U.S. Virgin Islands from the Virginia National Guard,[251] the West Virginia National Guard,[252] Missouri National Guard,[253] and UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters from the Tennessee Army National Guard.

Nearly a month after the hurricane, electricity had been restored to only 16 percent of people in St. Thomas and 1.6 percent of people in St. Croix.[254] Three months after Maria, about half the entire U.S. territory still had no power, and 25% of the U.S. territory had no cell service.[255]

Criticism of U.S. government response

The U.S. government hurricane response was criticized as inadequate and slow.[258] The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) did not immediately waive the Jones Act for Puerto Rico, which prevented the commonwealth from receiving any aid and supplies from non-U.S.-flagged vessels from U.S. ports (shipments from non-US ports were unaffected).[259] A DHS Security spokesman said that there would be enough U.S. shipping for Puerto Rico, and that the limiting factors would be port capacity and local transport capacity.[260][261][262] The Jones Act was ultimately waived for a period of ten days starting on September 28 following a formal request by Puerto Rico Governor Rosselló.[263]

San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz called the disaster a "terrifying humanitarian crisis" and on September 26 pleaded for relief efforts to be sped up.[264] The White House contested claims that the administration was not responding effectively.[265] General Joseph L. Lengyel, Chief of the National Guard Bureau, defended the Trump Administration's response, and reiterated that relief efforts were hampered by Puerto Rico being an island rather than on the mainland.[266] President Donald Trump responded to accusations that he does not care about Puerto Rico: "Puerto Rico is very important to me, and Puerto Rico—the people are fantastic people. I grew up in New York, so I know many people from Puerto Rico. I know many Puerto Ricans. And these are great people, and we have to help them. The island is devastated."[267]

Mayor Cruz criticized the federal response on September 29 during a news conference. "We are dying and you are killing us with the inefficiency", she said.[268] Trump responded by criticizing her for "poor leadership", and tweeted that the mayor and "others in Puerto Rico ... want everything to be done for them."[268]

Frustrated with the federal government's "slow and inadequate response", relief group Oxfam announced on October 2 that it planned to get involved in the humanitarian aid effort, sending a team to "assess a targeted and effective response" and support its local partners' on-the-ground efforts.[269] The organization released a statement, saying in part: "While the US government is engaged in relief efforts, it has failed to address the most urgent needs. Oxfam has monitored the response in Puerto Rico closely, and we are outraged at the slow and inadequate response the US Government has mounted," said Oxfam America's president Abby Maxman. "Oxfam rarely responds to humanitarian emergencies in the US and other wealthy countries, but as the situation in Puerto Rico worsens and the federal government's response continues to falter, we have decided to step in. The US has more than enough resources to mobilize an emergency response, but has failed to do so in a swift and robust manner."[270] In an update on October 19, the agency called the situation in Puerto Rico "unacceptable" and called for "a more robust and efficient response from the US government".[271]

On October 3, 2017, President Trump visited Puerto Rico. He compared the damage from Hurricane Maria to that of Hurricane Katrina, saying: "If you looked—every death is a horror, but if you look at a real catastrophe like Katrina, and you look at the tremendous hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people that died, and you look at what happened here with really a storm that was just totally overbearing, nobody has seen anything like this ... What is your death count as of this morning, 17?".[272] Trump's remarks were widely criticized for implying that Hurricane Maria was not a "real catastrophe".[273][274] While in Puerto Rico, Trump also distributed canned goods and paper towels to crowds gathered at a relief shelter[275] and told the residents of the devastated island "I hate to tell you, Puerto Rico, but you've thrown our budget a little out of whack, because we've spent a lot of money on Puerto Rico, and that's fine. We saved a lot of lives."[276]

On October 12, Trump tweeted, "We cannot keep FEMA, the Military & the First Responders, who have been amazing (under the most difficult circumstances) in P.R. forever!",[277] prompting further criticism from lawmakers in both parties;[278] Mayor Cruz replied, "You are incapable of empathy and frankly simply cannot get the job done."[187] In response to a request for clarification on the tweet from Governor Rosselló, John F. Kelly assured that no resources were being pulled and replied: "Our country will stand with those American citizens in Puerto Rico until the job is done".[279]

After visiting Puerto Rico about two months after the hurricane, Refugees International issued a report that severely criticized the slow response of the federal authorities, noted poor coordination and logistics, and indicated the island was still in an emergency mode and in need of more help.[193] Politico compared the federal response to Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico to that for Hurricane Harvey, which had hit the greater Houston area of Texas a month earlier. Though Maria caused catastrophic damage, the response was slower in quantitative terms.[268]

A Harvard Humanitarian Initiative analysis of the military deployment in March 2018 said the military mission in Puerto Rico after hurricane was better than critics say but suffered flaws. It concluded that the U.S. military itself performed as well in Puerto Rico as it does in its international relief missions, and that coordination had been greatly improved since Katrina, but that real shortcomings exist in planning for disasters.[280][281]

After the official death toll was updated to the estimated 2,975 on August 28, 2018, President Donald Trump stated that he still believed the federal government did a "fantastic job" in its hurricane response.[282] and less than a month later Trump described the federal response to Hurricane Maria as "an incredible, unsung success ... the best job we did was Puerto Rico [compared to hurricanes in Texas and Florida] but nobody would understand that". These remarks received condemnation from Carmen Yulín Cruz and other figures, who cited the near 3,000 death toll as not showing a success.[258]

A 2021 Inspector General investigation found that the Trump administration erected bureaucratic hurdles which stalled approximately $20 billion in hurricane relief for Puerto Rico.The Washington Post reported that President Donald Trump instructed officials to closely monitor Puerto Rico's disaster relief because he believed the island's government was corrupt. They also reported that he told his staff that he did not want a single dollar of relief funding to go Puerto Rico, instead pressing for the money to go to Florida and Texas.[283] The Trump Administration subsequently obstructed the efforts of the Department of Housing and Urban Development's Inspector General to investigate the delays in federal aid.[283]

Whitefish Energy contract

Soon after the hurricane struck, Whitefish Energy, a small Montana-based company with only two full-time employees, was awarded a $300 million contract by PREPA, Puerto Rico's state-run power company, to repair Puerto Rico's power grid, a move considered by many to be highly unusual for several reasons.[284] The company contracted more than 300 personnel, most of them subcontractors, and sent them to the island to carry out work. PREPA cited Whitefish's comparatively small upfront cost of $3.7 million for mobilization as one of the main reasons for contracting them over larger companies. PREPA Executive Director Ricardo Ramos stated: "Whitefish was the only company—it was the first that could be mobilized to Puerto Rico. It did not ask us to be paid soon or a guarantee to pay".[285] No requests for assistance had been made to the American Public Power Association by October 24.[285] The decision to hire such a tiny company was considered highly unusual by many, such as former Energy Department official Susan Tierney, who stated: "The fact that there are so many utilities with experience in this and a huge track record of helping each other out, it is at least odd why [the utility] would go to Whitefish".[284] Several representatives, both Democrats and Republicans, also voiced their concern over the choice to contract Whitefish instead of other companies.[285] As the company was based in Whitefish, Montana, the hometown of US Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, and one of Zinke's sons had once done a summer internship at Whitefish, Zinke knew Whitefish's CEO personally. These facts led to accusations of privatization and cronyism, though Zinke dismissed these claims and stated that he had no role in securing the contract.[284]

In a press release on October 27, FEMA stated it did not approve of PREPA's contract with Whitefish and cited "significant concerns".[286] Governor Rosselló subsequently ordered an audit of the contract's budget. DHS Inspector General John Roth led the FEMA audit while Governor Rosselló called for a second review by Puerto Rico's Office of Management and Budget.[287] The governor then demanded that the contract be canceled; this was executed on October 29.[288]

On April 18, 2018 (Wednesday), The Associated Press reported that the entire island experienced a blackout. On April 19, 2018 (Thursday), Puerto Rico's power company said that it had restored electricity to all customers affected by an island-wide blackout that was caused by an excavator hitting a transmission line, but tens of thousands of families still remained without normal service seven months after Hurricanes Maria and Irma.[289]

San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz said one week before the blackout that about 700,000 Americans in Puerto Rico did not have power after a line repaired by Montana contracting firm Whitefish Energy had failed. Puerto Rico's electric grid has suffered in the months since Hurricane Maria struck the island. The territory announced earlier in 2018 that it would privatize its power system over its "deficient service".[290]

Cruiseline French America Line claimed to be working with Whitefish Energy, and that their boat the "Louisiane" would serve as "headquarters for relief services" after Hurricane Maria.[291] Further investigation revealed that the boat had been docked in New Orleans since 2016. French America Line has been accused of scamming customers without delivering on services, and some have alleged the company used proposed "hurricane relief services" as a coverup.[291]

Retirement

Because of the extensive damage and loss of life the hurricane caused along its path, especially in Dominica, Saint Croix, and Puerto Rico, the World Meteorological Organization retired the name Maria from its rotating name lists in April 2018, and it will never again be used to name an Atlantic tropical cyclone. It was replaced with Margot for the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season.[292]

See also

- 2017 Puerto Rico Leptospirosis outbreak – an outbreak of leptospirosis that followed the hurricane

- List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- List of the deadliest tropical cyclones

- List of disasters by cost

- List of disasters in the United States by death toll

- Tropical cyclones and climate change

- Tropical cyclones in 2017

- Weather of 2017

- Other storms

- 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane – the deadliest hurricane in Puerto Rican history

- 1928 Okeechobee hurricane – A hurricane that made landfall on Puerto Rico at Category 5 intensity; the death toll on the island was much lower

- 1932 San Ciprian hurricane – another hurricane to make landfall on Puerto Rico at Category 4 strength or higher

- Hurricane David in 1979 – one of the deadliest tropical cyclones to hit Dominica

- Hurricane Hugo in 1989 – the last Category 4 hurricane to strike Saint Croix

- Hurricane Luis in 1995 – brought severe damage to several islands of the Lesser Antilles

- Hurricane Marilyn in 1995 – affected Dominica and Guadeloupe and brought severe damage to the U.S. Virgin Islands just a few days after Luis

- Hurricane Hortense in 1996 – affected Puerto Rico and caused widespread flooding across the island

- Hurricane Georges in 1998 – most recent major hurricane to strike Puerto Rico before Maria

- Hurricane Jeanne in 2004 – a Category 3 hurricane that devastated and killed the same number of people in Haiti

- Tropical Storm Erika in 2015 – devastated the island of Dominica with severe flooding

- Hurricane Irma in 2017 – Category 5 major hurricane that affected many of the same areas weeks before Hurricane Maria.

- Hurricane Jose in 2017 – major hurricane that passed dangerously close to some of the same areas that had just been affected by Hurricane Irma and were further affected by Maria.

- Hurricane Fiona in 2022 – a Category 4 hurricane with a similar track; affected Puerto Rico five years later and brought widespread flooding and island-wide total power outage

Notes

- ^ a b The storm category color indicates the intensity of the hurricane when landfalling in the U.S.

References

- ^ Baldwin, Sarah Lynch; Begnaud, David (August 28, 2018). "Hurricane Maria caused an estimated 2,975 deaths in Puerto Rico, new study finds". CBS News. Archived from the original on August 28, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch; Andrew B. Penny; Robbie Berg (April 5, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Maria (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Giusti, Carlos (June 13, 2018). "Puerto Rico issues new data on Hurricane Maria deaths". NBC News. Archived from the original on June 18, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ a b Baldwin, Sarah Lynch; Begnaud, David (August 28, 2018). "Hurricane Maria caused an estimated 2,975 deaths in Puerto Rico, new study finds". CBS News. Archived from the original on August 28, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Richard J. Pasch; Andrew B. Penny; Robbie Berg (April 5, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Maria (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Neely, Wayne (December 19, 2016). The Greatest and Deadliest Hurricanes of the Caribbean and the Americas: The Stories Behind the Great Storms of the North Atlantic. iUniverse. p. 375. ISBN 978-1-5320-1151-1. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ^ Sean Breslin (August 9, 2018). "Puerto Rican Government Admits Hurricane Maria Death Toll Was at Least 1,400". The Weather Company. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ^ Blake, Eric (September 14, 2017). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ Blake, Eric (September 15, 2017). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ Cangialosi, John (September 16, 2017). Tropical Storm Maria Discussion Number 2. National Hurricane Center (Report). Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ Cangialosi, John (September 17, 2017). "Hurricane Maria Discussion Number 6". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ Brown, Daniel; Blake, Eric (September 18, 2017). Hurricane Maria Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Brown, Daniel; Blake, Eric (September 18, 2017). Hurricane Maria Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.