Resonance (sociology)

Resonance is a quality of human relationships with the world proposed by Hartmut Rosa. Rosa, professor of sociology at the University of Jena, conceptualised resonance theory in Resonanz (2016) to explain social phenomena through a fundamental human impulse towards "resonant" relationships.[1]

Background

[edit]Rosa outlined the cause of several crises of modernity in his monograph on social acceleration and dynamic stabilisation.[2] In this monograph, Rosa put forward social acceleration as the cultural logic of modernity and the cause of the modern burnout crisis, environmental issues, and mass alienation.[3] Resonance sets out to provide a solution to the alienation caused by social acceleration in late modernity.[3] He theorises that resonance, a normative experience in which an individual experiences a transformational, responsive, and affectual relationship to the world, is the solution to the extremes of alienation caused by modernity.[3]

Definition

[edit]With the aim of theorising a sociology of 'the good' in dialectical opposite to alienation, Rosa outlines the following definition of resonance:

...a kind of relationship to the world, formed through affect and emotion, intrinsic interest, and perceived self-efficacy, in which subject and world are mutually affected and transformed.

Resonance is not an echo, but a responsive relationship, requiring that both sides speak with their own voice. This is only possible where strong evaluations are affected. Resonance implies an aspect of constitutive inaccessibility.

Resonant relationships require that both subject and world be sufficiently “closed” or self-consistent so as to each speak in their own voice, while also remaining open enough to be affected or reached by each other.

Resonance is not an emotional state, but a mode of relation that is neutral with respect to emotional content. This is why we can love sad stories.[3]

Overview

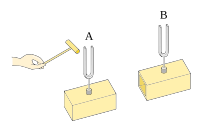

[edit]The acoustic term resonance describes a subject–object relationship as a vibrating system in which both sides mutually stimulate each other. However, as with a tuning fork, they do not merely return the received sound, but speak "with their own voice". According to Rosa, the subjects' relational abilities and sense of their places in the world are influenced and reformed by such resonant experiences. Negative or alienated experiences, then, are those which lack resonance, and provide what Rahel Jaeggi terms 'a relation of relationlessness'.[3][4] Resonance is therefore a way of approaching the question of successful relations between subject and world in the sense of "good life", which marks a significant departure from a critical theory primarily focused on relations of alienation.[5]

The possible points of reference of such resonances are ubiquitous and are described in four axes:

- Horizontal resonances take place between two (or more) people, in love and family relationships, friendships or political space.

- Diagonal resonance axes are relationships to the world of things and regular activities, such as school or sports practice.

- Vertical resonance axes are relationships to abstract, ontological categories, such as nature, art, history or religion.

- A recent fourth addition to resonance theory by Rosa is the axis of the self, the extent to which one feels a non-alienated sense of relation with their own body and psyche.[6]

For instance, a horizontal relationship of resonance is evidenced in the relationship between the newborn and primary caregivers, by whose reception or rejection of interactions the fundamental attachment patterns develop. Diagonal resonances, are conveyed by Rosa through Rainer Maria Rilke's conception of 'The singing of things', which conveys a feeling of being called by material things, such as mountains, artworks or household possessions.[7] Feeling part of nature, an epoch of history, or a moment of worship is accounted for in the vertical axis resonance.

In all these contexts, resonant experiences are juxtaposed with silent or instrumental world relations, determined by an orientation towards domination and attaining resources, which are primarily concerned with the achievement of a useful goal.[5] For example, a mountain tour aimed at tourists can either be a resonant experience (as an opportunity to confront the beautiful but challenging walk), or a more purpose-oriented, instrumental, and therefore, "mute" experience.

Relations that are controlling, hostile or anixous result in "silent", non-resonant experiences. Rosa argues that much of consumer culture promises resonance commenting "Buy yourself resonance! is the implicit siren song of nearly all advertising campaigns and sales pitches." However, the attempt to control the experience of resonance ends up inhibiting the experience by instrumentalising it. Rosa argues that mediopassivity, a stance of the subject being not entirely active or passive in an experience allows enough uncontrollability for resonance to take place.[8][9] Another prerequisite for the establishment of resonances are the strong evaluations of the subject, which give the object a significance that goes beyond desire or attractiveness.

If an attempt is made to outline as resonance what people seek and long for in their innermost being, it is by no means conceived as a permanent state that can be established, but always as a selective, momentary success or self-transformation that stands out against the background of a world that is predominantly silent, instrumental. Resonance in this sense is therefore essentially characterized by the fact that it cannot be produced systematically and intentionally, but is ultimately unavailable. Nevertheless, Rosa calls for institutional reforms which are geared towards resonance and avoid the kinds of extractive instrumental activity which cause alienation.[1]

Social theory

[edit]As a sociological theory, resonance theory deals with the social conditions that promote or hinder successful world relationships. The conditions of modernity have created what he terms social acceleration, an approach to time which is geared towards increasing resources and innovations in as short a time as possible.[2] This results in a logic of increase, which requires a constant continuation of improvement and multiplication of resources. This is accompanied by an increasing pressure to accelerate: in order to maintain the status quo within a modern society, societies must continually increase the number of services, innovations and material production opportunities. Rosa sees this mode of dynamic stabilization as the defining characteristic of modernity.[2] While pre-modern societies transform themselves adaptively, i.e. in response to changed conditions, modern society is virtually defined by its compulsion for continuous economic, social and technological transformation.[10]

While the current phase of late modernism is characterized by a high resonance sensitivity and expectation of its subjects, the mode of dynamic stabilization results in a loss of resonance. Rosa notes three essential manifestations of the current crisis of modernity:

- the ecological crisis due to the rapid extraction of nature's finite resources feeding an unlimited expectation of increase

- the political crisis, arising from democratic negotiation processes being too slow to keep up with accelerated technological change, resulting in social changes which are therefore regarded as ineffective or obsolete

- the psychological crisis of the subjects, overwhelmed by acceleration and therefore experiencing burnout

Resonance theory is thus in the tradition of critical theory from Marx to Adorno and Horkheimer to Habermas and Honneth.[3] It shares the central finding of alienation as an obstacle to a successful life, but attempts to contrast this with a positive counter-concept, the concept of resonance. Honneth, for example, has already made this attempt with the concept of recognition.[11] Despite critiques of the vagueness of the concept of resonance, Rosa sees this as a universal concept that includes concepts such as recognition, justice or self-efficacy.

Policies

[edit]Rosa says that “this sociology of human relationships to the world does not pursue its own political agenda”.[3] However, he claims that resonance can serve as a driver in political debates, providing a standard for action.[3] He lists, for instance:

- Preserving resonances in how we interact with the natural world. For instance, problematising practices such as animal testing and mass factory farming

- Recognition of labor as valuable as a sphere of resonance, rather than mere economic output

- Schools being made into resonance spaces which seek to reduce alienation

- A democratic arrangement that sees democracy as an instrument for “adaptively transforming public institutions, formative structures, and the shared lifeworld, and thus creates opportunities for the experience of genuine collective self-efficacy”[3]

Rosa finds some consonance between resonance and Habermas's concept of communicative action.[12][3] However, he criticises Habermas for mainly considering ‘intersubjective resonant relationships’, and ignoring relationships to the world, to things, and non-humans.[3] Moreover, he suggests that Habermas overlooks the aesthetic and emotional relationships evidenced in Fromm, Marcuse and Adorno. He finds more alignment in Honneth’s theory of recognition, in which:

…understanding is geared toward inner accordance with and the communicative accommodation of Others … recognition, in the three forms of love/friendship, legal recognition, and social esteem, establishes three kinds of resonant axes to the social world that allow individuals to experience self-confidence, self-respect, and self-esteem.[2]

In advocating for a system which emphasises a plurality of voices and is critical of escalatory logics, resonance is critical of both excessive bureaucracy and social acceleration. Rosa advocates for policies which help achieve a ‘paradigm shift from the logic of escalation to sensitivity to resonance', prefacing that “This does not mean that there be no space for competition in markets”, but instead more regulation against "blind escalation".[3]

Reception

[edit]Rosa has been credited for his search for a far-reaching framework for addressing social issues issues in a matter quite contrasted with a critical theory which looks at the world in negative terms, often summarised with Adorno's "There is no right life in the wrong one".[5] Such an appreciation of resonance theory as a positive continuation of critical theory can be found with Anna Henkel.[5] Micha Brumlik sees in the comprehensive combination of interdisciplinary strands the completion, but with it also the end, of critical theory, which thereby loses its "theoretically informed irreconcilability looking coldly at society". On the other hand, Brumlik states that this comprehensive derivation of the concept of resonance from a multitude of perspectives and contexts is flawed since "resonance" has an almost arbitrary effect that lacks conceptual precision.[5] Brumlik concludes that it is therefore ultimately unsuitable as a social-philosophical basic concept.[5]

Other critics refer to Rosa's alleged recourse to the intellectual world of Romanticism.[13] Rosa does indeed frequently refer to the sensitivity to resonance implicit in Romanticism, even in conscious contradiction of rationalist concepts, but at the same time sees the danger of Romanticism's championing of purely subjective emotion instead of resonance.[1] Thus he rather describes the continuing effect of the resonance concepts of Romanticism in modernity, without propagating a return to it.[1]

Rosa's book argues that the socio-political outlook on concrete solutions is poor and he has publicly shared his dissatisfaction with the paths to post-growth suggested in his original monograph.[3][14] Despite reference to political reform proposals such as that of a universal basic income and emerging pilot projects of post-growth economies, Rosa does not necessarily provide a direct route to this:

It is akin to the question of how humanity was able to move out of the social formations of the “Middle Ages” into modernity. Both cases involve a fundamental transformation of humanity’s relationship to the world that sets subjective and institutional, cultural and structural, cognitive, affective and habitual levels in motion all at once, without either a clear starting point or a unilinear direction of propagation. The theory of resonance articulated here, however, attempts to provide a small building block by at least making it possible to again perceive a different form of existence.[3]

Literary theorist Rita Felski, one of the originators of postcritique, which advocates for a literary theory which moves beyond the hermeneutics of suspicion, has celebrated resonance theory as an educational approach which is inclusive of both critical theory and aesthetic appreciation.[15] Felski argues that resonance provides an alternative to parametric and instrumental approaches to education, and makes the case for educational experiences that "speak[s] to the force of intellectual engagement for its own sake", based on attachment, enchantment and affect.[15]

There is a particular interest in Rosa's ideas in education research. Several studies investigating the possibility of resonant school structures and pedagogies have been published.[16][17][18][19][20]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Rosa, Hartmut (2016). Resonanz. Eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung. Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag. ISBN 978-3-518-58626-6.

- ^ a b c d Rosa, Hartmut (2013). Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity. Translated by Wagner, James. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14835-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Rosa, Hartmut (2019). Resonance: A Sociology of our Relationship to the World. Translated by Wagner, James. Polity.

- ^ Jaeggi, Rahel; Neuhouser, Frederick; Smith, Alan (2014-08-26). Alienation. Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/columbia/9780231151986.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-231-15198-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Brumlik, Micha. Resonanz oder: Das Ende der kritischen Theorie. pp. 120–123.

- ^ Rosa, Hartmut (2018). "The idea of resonance as a sociological concept". Global Dialogue. 8 (2): 41–44.

- ^ Shabasson, Daniel S (2015). "English translation of Rilke's poem "Ich furchte mich so vor der Menschen Wort "Menschen Wort"". Academic Works.

- ^ Rosa, Hartmut Rosa (2020). The Uncontrollability of the World. Polity.

- ^ Rosa, Hartmut (2023). "Resonance as a medio-passive, emancipatory and transformative power: a reply to my critics". The Journal of Chinese Sociology. 10 (1). doi:10.1186/s40711-023-00195-4.

- ^ a b Rosa, Hartmut (2015). Beschleunigung: die Veränderung der Zeitstrukturen in der Moderne. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. ISBN 978-3-518-29360-7.

- ^ Honneth, Axel (2012). The I in We: studies in the theory of recognition. Cambridge: Polity press. ISBN 978-0-7456-5233-7.

- ^ "The communicative concept of action", Understanding Habermas : Communicative Action and Deliberative Democracy, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1-4742-1321-9, retrieved 2024-04-30

- ^ Thomä, Dieter (8 July 2016). Hartmut Rosa: Soziologie mit der Stimmgabel. ISSN 0044-2070.

- ^ "Against Aggression: Monstrous and Resonant Forms of Uncontrollability". YouTube. Nov 28, 2023. 1:23:30. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ a b Felski, Rita (2020). "Resonance and Education". Journal for Research and Debate. 3 (9). doi:10.17899/on_ed.2020.9.2. ISSN 2571-7855.

- ^ Prouteau, François; Hétier, Renaud; Wallenhorst, Nathanaël (2022-06-15). "Critique, Utopia and Resistance: Three Functions of Pedagogy of Resonance in the Anthropocene". Vierteljahrsschrift für wissenschaftliche Pädagogik. 98 (2): 202–215. doi:10.30965/25890581-09703042. ISSN 0507-7230. S2CID 251428034.

- ^ Frydendal, Stine; Thing, Lone Friis (2023-01-05). "PE as resonance? The role of physical education in an accelerated education system". Sport, Education and Society: 1–13. doi:10.1080/13573322.2022.2161502. ISSN 1357-3322. S2CID 255721204.

- ^ Göllner, Michael; Honnens, Johann; Krupp, Valerie; Oravec, Lina; Schmid, Silke, eds. (2023). 44. Jahresband des Arbeitskreises Musikpädagogische Forschung: = 44th Yearbook of the German Association for Research in Music Education. Musikpädagogische Forschung Research in Music Education. Münster New York: Waxmann. ISBN 978-3-8309-4764-6.

- ^ López-Deflory, Camelia; Perron, Amélie; Miró-Bonet, Margalida (2023). "Social acceleration, alienation, and resonance: Hartmut Rosa's writings applied to nursing". Nursing Inquiry. 30 (2): e12528. doi:10.1111/nin.12528. hdl:20.500.13003/18260. ISSN 1320-7881. PMID 36115014.

- ^ Shim, Seung-hwan (2022-12-08). "Resonance as an educational response to alienation and acceleration in contemporary society". Asia Pacific Education Review. doi:10.1007/s12564-022-09814-0. ISSN 1598-1037. S2CID 254479780.