Hannah Wilke

Hannah Wilke | |

|---|---|

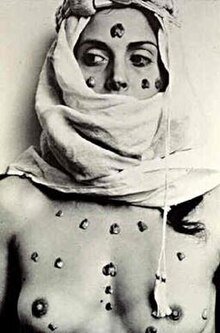

Wilke in her work S.O.S. — Starification Object Series (1974) | |

| Born | Arlene Hannah Butter March 7, 1940 |

| Died | January 28, 1993 (aged 52) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Stella Elkins Tyler School of Fine Art, Temple U, Philadelphia |

| Known for | Sculpture, photography, body art, video art |

| Notable work | S.O.S. — Starification Object Series (1974) Intra-Venus (1992–1993) |

| Awards | NEA Grants in sculpture and performance, Guggenheim Grant for sculpture |

Hannah Wilke (born Arlene Hannah Butter; (March 7, 1940 – January 28, 1993)[1] was an American painter, sculptor, photographer, video artist and performance artist. Her work is known for exploring issues of feminism, sexuality and femininity.[2]

Biography

[edit]Hannah Wilke was born on March 7, 1940, in New York City to Jewish parents; her grandparents were Eastern European immigrants. She graduated from Great Neck North High School, on Long Island, in 1957.[3] In 1962, she received a Bachelor of Fine Arts and a Bachelor of Science in Education from the Tyler School of Art, Temple University, Philadelphia. She taught art in several high schools for approximately 30 years and joined the faculty of the School of Visual Arts. After her graduation the same year she taught art at two high schools. First, Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania (1961-1965), between 1965 and 1970 she worked in White Plains, New York. After leaving White Plains, she joined the School of Visual Arts, in New York (1972-1991).[4]

From 1969 to 1977, Wilke was in a relationship with the American Pop artist Claes Oldenburg; they lived, worked and traveled together during that time.[5][6][7] Wilke's work was exhibited[8] nationally and internationally throughout her life and continues to be shown posthumously.[9] Solo exhibitions of her work were first mounted in New York and Los Angeles in 1972. Her first full museum exhibition was held at the University of California, Irvine, in 1976, and her first retrospective at the University of Missouri in 1989.

Posthumous retrospectives were held in Copenhagen, Helsinki, and Malmö, Sweden in 2000 and at the Neuberger Museum of Art from 2008 to 2009. Since her death, Wilke's work has been shown in solo gallery shows, group exhibitions, and several surveys of women's art, including WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution[10] at the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, Elles at the Centre Georges Pompidou, and Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women, 1947 – 2016 at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles.[11]

The Hannah Wilke Collection and Archive, Los Angeles was founded in 1999 by Hannah Wilke's sister Marsie Scharlatt and her family,[12] and has been represented by Alison Jacques Gallery, London since 2009.[13]

Her image is included in the iconic 1972 poster Some Living American Women Artists by Mary Beth Edelson.[14]

Early work

[edit]Wilke first gained renown with her "vulval" terra-cotta sculptures in the 1960s.[15] Her sculptures, first exhibited in New York in the late 1960s, are often mentioned as some of the first explicit vaginal imagery arising from the women's liberation movement,[15] and they became her signature form which she made in various media, colors and sizes, including large floor installations, throughout her life.[8][16] Some of her mediums included clay, chewing gum, kneaded erasers, laundry lint and latex.[2] The use of unconventional materials is typical of feminist art, nodding to women's historical lack of access to traditional art supplies and education.[17] Furthermore, Wilke reported that the reason she chose chewing gum was because ″it's the perfect metaphor for the American women—chew her up, get what you want out of her, throw her out and pop in a new piece.″[18] Wilke's sculptures were an innovative example of eroticism using a style that combined post-minimalism and feminist aesthetics.[19] A consummate draftswoman, Wilke created numerous drawings, beginning in the early 1960s and continuing throughout her life. In a review of Wilke's drawings at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts in 2010, Thomas Micchelli wrote in The Brooklyn Rail, "At her core, she was a maker of things ... an artist whose sensuality and humor are matched by her formal acumen and tactile rigor."[20] She performed live and videotaped performance art, beginning in 1974 with Hannah Wilke Super-t-Art, a live performance at the Kitchen, New York, which she also made into an iconic photographic work. Wilke's performances evoke the likes of Simone Forti, Trisha Brown, and Yvonne Rainer. The sculptural art Wilke created, with its unconventional materials and feminist narratives also relates to the work of Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alina Szapocznikow, and Niki de St Phalle.

Body art

[edit]In 1974, Wilke began work on her photographic body art piece S.O.S — Starification Object Series, in which she merged her minimalist sculpture and her own body by creating tiny vulval sculptures out of chewing gum and sticking them to herself.[15] She then had herself photographed in various pin-up poses, providing a juxtaposition of glamour and something resembling tribal scarification.[15] Wilke has related the scarring on her body to an awareness of the Holocaust. These poses exaggerate and satirize American cultural values of feminine beauty and fashion and also hint at an interest in ceremonial scarification.[21] The 50 self-portraits were originally created as a game, "S.O.S.Starificaion Object Series: An Adult Game of Mastication", 1974–75, which Wilke made into an installation that is now in the Centre Pompidou, Paris. She also performed this piece publicly in Paris in 1975, having audience members chew the gum for her before she sculpted them and placed them on papers that she hung on the wall.[21] Wilke also used colored chewing gum as a medium for individual sculptures, using multiple pieces of gum to create a complex layering representing the vulva.[22] Wilke's use of vaginas and vulvas refer to her idea of ″natural womanhood″, in order to support her argument that women are biologically superior.[18] Later on in 1976 she once again conjured the pin-up poses in her self-portrait, Marxism and Art: Beware of Fascist Feminism.

Wilke coined the term "performalist self-portraits" to credit photographers who assisted her, including her father (First Performalist Self-Portrait, 1942–77) and her sister, Marsie (Butter) Scharlatt (Arlene Hannah Butter and Cover of Appearances, 1954–77). The title of Wilke's photographic and performance work, So Help Me Hannah, 1979, was taken from a vernacular phrase from the 1930s and '40s and has been interpreted as playing off of the Jewish mother stereotype and referencing Wilke's relationship with her mother.[23]

Besides Hannah Wilke Super-t-Art, 1974, other well-known performances in which Wilke used her body include Gestures, 1974; Hello Boys, 1975; Intercourse with ... (audio installation) 1974–1976; Intercourse with ... (video) 1976; and Hannah Wilke Through the Large Glass performed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1977.

Death and Intra-Venus

[edit]Hannah Wilke died in Houston, Texas, in 1993 from lymphoma.[1][24] Her last work, Intra-Venus (1992–1993), is a posthumously published photographic record of her physical transformation and deterioration resulting from chemotherapy and bone marrow transplant.[25] The photographs, which were taken by her husband Donald Goddard whom she had lived with since 1982 and married in 1992 shortly before her death, confront the viewer with personal images of Wilke progressing from midlife happiness to bald, damaged, and resigned.[25] Intra-Venus mirrors her photo diptych Portrait of the Artist with Her Mother, Selma Butter, 1978–82, which portrayed her mother's struggles with breast cancer and "having literally incorporated her mother, illness and all."[26] Intra-Venus was exhibited and published posthumously partially in response to Wilke's feelings that clinical procedures hide patients as if dying were a "personal shame".[27]

The Intra-Venus works also include watercolor Face and Hand drawings, Brushstrokes, a series of drawings made from her own hair and the Intra-Venus Tapes, a 16-channel videotape installation.[28]

Pose and narcissism

[edit]Wilke often features herself as a posing glamour model. Her use of self in photography and performance art, however, has been interpreted as a celebration and validation of Self, Women, the Feminine, and Feminism.[29][30] Conversely, it has also been described as an artistic deconstruction of cultural modes of female vanity, narcissism, and beauty.[31][32]

Wilke referred to herself as a feminist artist from the beginning.[33] The art critic Ann-Sargent Wooster said that Wilke's identification with the feminist movement was confusing because of her beauty — her self-portraitures looked more like a Playboy centerfold than the typical feminist nudes.[33] According to Wooster,

The problem Wilke faced in being taken seriously is that she was conventionally beautiful and her beauty and self-absorbed narcissism distracted you from her reversal of the voyeurism inherent in women as sex objects. In her photographs of herself as a goddess, a living incarnation of great works of art or as a pin-up, she wrested the means of production of the female image from male hands and put them in her own.[33]

If critics found Wilke's beauty an impediment to understanding her work, this changed in the early 1990s when Wilke began documenting the decay of her body ravaged by lymphoma. Wilke's use of self-portraiture has been explored in detail in writing about her last photographic series, Intra Venus.[34]

Wilke once answered the critics who commented on her body being too beautiful for her work by saying "People give me this bullshit of, 'What would you have done if you weren't so gorgeous?' What difference does it make? ... Gorgeous people die as do the stereotypical 'ugly.' Everybody dies.[35]"

Critical recognition

[edit]During her lifetime, Wilke was widely exhibited and received critical praise while also being viewed as controversial. However, until recently, museums were hesitant to acquire work by women artists who, including Wilke, engaged in protests decrying their lack of inclusion during the feminist movement of the 1970s.[36] While still alive, Wilke's work was in a few permanent collections, showcasing the confrontational use of the female sexuality. Since her death, Wilke's work has been acquired for the permanent collections of The Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and in European museums such as the Centre Pompidou, Paris.[37]

Solo exhibitions

[edit]- 1976, Fine Arts Gallery, University of California, Irvine

- 1978, MoMA PS1, Long Island City, New York

- 1979, Washington Project for the Arts, Washington, DC

- 1989, Gallery 210, University of Missouri, St Louis

- 1998, Hannah Wilke: A Retrospective, Nikolaj Contemporary Art Center, Copenhagen (traveling exhibition)[38]

- 2000, Uninterrupted Career: Hannah Wilke 1940–1993, Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin[2]

- 2006, Exchange Values, Artium- Centro Museo Vasco de Arte Contemporaneo, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain[39]

- 2008, Hannah Wilke: Gestures, Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, New York[40]

- 2021, Hannah Wilke: Art for Life’s Sake, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, St. Louis [41]

Awards

[edit]She received a Creative Artists Public Service Grant (1973); National Endowment for the Arts Grants (1987, 1980, 1979, 1976); Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grants (1992, 1987); a Guggenheim Fellowship (1982), and an International Association of Art Critics Award (1993).[2][better source needed]

Collections

[edit]Wilke's work is held in the following permanent collections:

- Brooklyn Museum[42]

- Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY[43]

- Des Moines Art Center[44]

- Tate, U.K.[45]

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art[46]

- Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain[47]

- Walker Arts Center, Minneapolis, MN[48]

- Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT[49]

- Jewish Museum, New York, NY[50]

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY[51]

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY[52]

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY[53]

- Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, OH[54]

- Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France[55]

- Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ[56]

- David Winton Bell Gallery, Brown University, Providence, RI[57]

- Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, NV[58]

- Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA[2]

- University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, MI[59]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Smith, Roberta (1994-01-30). "ART VIEW; An Artist's Chronicle Of a Death Foretold". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

- ^ a b c d e "Hannah Wilke". Oxford Art Online.[dead link]

- ^ "Ancestry Library Edition".

- ^ "The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation".

- ^ Marsie Scharlatt, "Hannah in California," in Hannah Wilke: Selected Work, 1963-1992, Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles, and SolwayJones, Los Angeles, 2004.

- ^ Tracy Fitzpatrick, "Making Myself into a Monument," Gestures, Neuberger Museum of Art, 2009

- ^ Nancy Princenthal, Hannah Wilke, Prestel Publishing, 2010

- ^ a b "Hannah Wilke: Biography, Exhibitions, Awards, HWCALA". Archived from the original on May 28, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ "EXHIBITIONS". Archived from the original on January 25, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ "WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution". The Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- ^ "Exhibitions — Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women, 1947 – 2016 - Louise Bourgeois, Isa Genzken, Phyllida Barlow, Anna Maria Maiolino, Lygia Pape, Eva Hesse, Mira Schendel, Rachel Khedoori - Hauser & Wirth". www.hauserwirth.com. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- ^ "Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles". HANNAH WILKE COLLECTION & ARCHIVE, LOS ANGELES. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ "Hannah Wilke". Alison Jacques Gallery. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ "Some Living American Women Artists/Last Supper". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d Buszek, Maria Elena (2006). "Our Bodies/Ourselves". Pin-up Grrrls: Feminism, Sexuality, Popular Culture. Duke University Press. pp. 291–294. ISBN 0-8223-3746-0.

- ^ Tracy Fitzpatrick, Gestures, Neuberger Museum of Art, 2009

- ^ Schapiro, Miriam (1977–78). "Waste Not Want Not". Heresies 1 (4): 153.

- ^ a b "Hannah Wilke Used Her Body as a Canvas to Subvert the Patriarchy". January 2019.

- ^ Middleman, Rachel (2013). "Rethinking Vaginal Iconology with Hannah Wilke's Sculpture". Art Journal. 72 (4): 34–45. doi:10.1080/00043249.2013.10792862. S2CID 194070541. ProQuest 1710658672.

- ^ Micchelli, Thomas (October 2010). "HANNAH WILKE Early Drawings". The Brooklyn Rail.

- ^ a b Wacks, Debra; Goldman, Saundra; Fischer, Alfred M.; Cottingham, Laura (Summer 1999). "Naked Truths: Hannah Wilke in Copenhagen". Art Journal. 58 (2). College Art Association: 104–106. doi:10.2307/777953. JSTOR 777953.

- ^ Dick, Leslie. "Hannah Wilke". X-TRA. 6 (4). Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ Princenthal, Nancy (February 1997). "Mirror of Venus — photography, videos and performance art, Hannah Wilke, Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York, New York". Art in America. 85 (2): 92–93. Archived from the original on 2007-12-16. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ "Hannah Wilke". Guggenheim. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- ^ a b Tierney, Hanne (January 1996). "Hannah Wilke: The Intra-Venus Photographs". Performing Arts Journal. 18 (1): 44–49. JSTOR 3245813.

- ^ Jones, Amelia (1998). "The Rhetoric of the Pose: Hannah Wilke". Body Art/Performing the Subject. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 189. ISBN 0-8166-2773-8.

- ^ Vine, Richard (May 1994). "Hannah Wilke at Ronald Feldman — New York, New York — Review of Exhibitions". Art in America. Archived from the original on 2007-10-28. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ "Hannah Wilke Biography, Art, and Analysis of Works". The Art Story. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ^ Joanna Frueh, "Hannah Wilke," in Hannah Wilke: A Retrospective, University of Missouri Press, 1989.

- ^ Arlene Raven,"The Eternal Hannah Wilke," in Hannah Wilke: Selected Works, 1963-1992, Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles and SolwayJones, Los Angeles

- ^ Toepfer, Karl (September 1996). "Nudity and Textuality in Postmodern Performance". Performing Arts Journal. 18 (3): 82–83. JSTOR 3245676.

- ^ Jones (1998), pp.151-152.

- ^ a b c Wooster, Ann-Sargent (Fall 1990). "Hannah Wilke: Whose Image is it anyway". High Performance.

- ^ Amelia Jones, "Hannah Wilke's Feminist Narcissism," Intra Venus, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, 1994.

- ^ "Everybody Dies ... Even the Gorgeous: Resurrecting the Work of Hannah Wilke" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-05.

- ^ Nancy Princenthal, Hannah Wilke, Prestel, 2010

- ^ "Hannah Wilke Art in Selected Public Collections".

- ^ "Hannah Wilke (retrospective) | www.nikolajkunsthal.dk". www.nikolajkunsthal.dk. Archived from the original on 2018-03-12. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- ^ "Hannah Wilke. Exchange Values". www.artium.eus (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2019-07-31.

- ^ "Hannah Wilke: Gestures". Neuberger Museum of Art. Retrieved 2019-07-31.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Hannah Wilke: Art for Life's Sake". pulitzerrarts.org. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum: Hannah Wilke". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- ^ "Untitled, from the Hannah Wilke Monument | Albright-Knox". www.albrightknox.org. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- ^ "Marxism and Art: Beware of Fascist Feminism – Works – Des Moines Art Center". emuseum.desmoinesartcenter.org. Archived from the original on 2018-03-12. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- ^ Tate. "Hannah Wilke 1940-1993 | Tate". Tate. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- ^ "Hannah Wilke | LACMA Collections". collections.lacma.org. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- ^ "Wilke, Hannah". www.museoreinasofia.es. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- ^ "Teasel Cushion". walkerart.org. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- ^ "U.S.S. Missouri". artgallery.yale.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ^ "The Jewish Museum". thejewishmuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ^ "Collection". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ^ "S.O.S. Starification Object Series (Back)". Guggenheim. 1974-01-01. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ^ "Whitney Museum of American Art: Hannah Wilke". collection.whitney.org. Archived from the original on 2018-03-12. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ^ "eMuseum". allenartcollection.oberlin.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-12.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Hannah Wilke | Centre Pompidou". Archived from the original on 2018-03-12. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ^ "Hannah Wilke | Princeton University Art Museum". artmuseum.princeton.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-04-29. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ^ "Search the Collection | David Winton Bell Gallery". www.brown.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ^ "Hannah Wilke, Mountain Creek".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Exchange: Handle with Care". exchange.umma.umich.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Nancy Princenthal, Hannah Wilke (Prestel USA, 2010)

- ! Woman art revolution, Documentary trailer shows rare footage of Wilke speaking in 1991, less than two years before her death. The trailer also shows examples of her Intra-Venus series: portraits of her body ravaged by lymphoma.

- American conceptual artists

- American women conceptual artists

- Conceptual photographers

- American feminist artists

- 1940 births

- 1993 deaths

- Artists from New York City

- American modern sculptors

- Jewish American artists

- Temple University Tyler School of Art alumni

- 20th-century American photographers

- 20th-century American sculptors

- Burials at Green River Cemetery

- Jewish American feminists

- 20th-century American women photographers

- Deaths from lymphoma in Texas

- Postminimalist artists

- 20th-century American Jews

- 20th-century American women sculptors