Marina Abramović

Marina Abramović | |

|---|---|

Марина Абрамовић | |

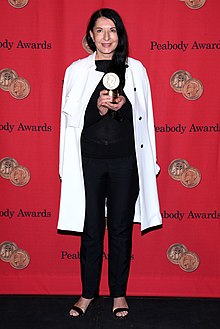

Abramović in 2024 | |

| Born | November 30, 1946 |

| Education |

|

| Known for | |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Conceptual art/signalism |

| Spouses | |

| Partner | Ulay (1976–1988) |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Varnava, Serbian Patriarch (great-uncle) |

| Website | mai |

Marina Abramović (Serbian Cyrillic: Марина Абрамовић, pronounced [marǐːna abrǎːmovitɕ]; born November 30, 1946) is a Serbian conceptual and performance artist. Her work explores body art, endurance art, the relationship between the performer and audience, the limits of the body, and the possibilities of the mind.[1] Being active for over four decades, Abramović refers to herself as the "grandmother of performance art".[2] She pioneered a new notion of identity by bringing in the participation of observers, focusing on "confronting pain, blood, and physical limits of the body".[3] In 2007, she founded the Marina Abramović Institute (MAI), a non-profit foundation for performance art.[4][5]

Early life, education and teaching

[edit]Abramović was born in Belgrade, Serbia, then part of Yugoslavia, on November 30, 1946. In an interview, Abramović described her family as having been "Red bourgeoisie".[6] Her great-uncle was Varnava, Serbian Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church.[7][8] Both of her Montenegrin-born parents, Danica Rosić and Vojin Abramović,[6] were Yugoslav Partisans[9] during World War II. After the war, Abramović's parents were awarded Order of the People's Heroes and were given positions in the postwar Yugoslavian government.[6]

Abramović was raised by her grandparents until she was six years old.[10] Her grandmother was deeply religious and Abramović "spent [her] childhood in a church following [her] grandmother's rituals—candles in the morning, the priest coming for different occasions".[10] When she was six, her brother was born, and she began living with her parents while also taking piano, French, and English lessons.[10] Although she did not take art lessons, she took an early interest in art[10] and enjoyed painting as a child.[6]

Life in Abramović's parental home under her mother's strict supervision was difficult.[11] When Abramović was a child, her mother beat her for "supposedly showing off".[6] In an interview published in 1998, Abramović described how her "mother took complete military-style control of me and my brother. I was not allowed to leave the house after 10 o'clock at night until I was 29 years old. ... [A]ll the performances in Yugoslavia I did before 10 o'clock in the evening because I had to be home then. It's completely insane, but all of my cutting myself, whipping myself, burning myself, almost losing my life in 'The Firestar'—everything was done before 10 in the evening."[12]

In an interview published in 2013, Abramović said, "My mother and father had a terrible marriage."[13] Describing an incident when her father smashed 12 champagne glasses and left the house, she said, "It was the most horrible moment of my childhood."[13]

Education and teaching career

[edit]She was a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade from 1965 to 1970. She completed her post-graduate studies in the art class of Krsto Hegedušić at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, SR Croatia, in 1972. Then she returned to SR Serbia and, from 1973 to 1975, taught at the Academy of Fine Arts at Novi Sad while launching her first solo performances.[14] See also: Role Exchange (1975 performative artwork)

In 1976, following her marriage to Neša Paripović (between 1970 and 1976), Abramović went to Amsterdam to perform a piece[15] and then decided to move there permanently.

From 1990 to 1995, Abramović was a visiting professor at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris and at the Berlin University of the Arts. From 1992 to 1996 she also served as a visiting professor at the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg and from 1997 to 2004 she was a professor for performance-art at the Hochschule für bildende Künste Braunschweig.[16][17]

Career

[edit]Rhythm 10, 1973

[edit]In her first performance in Edinburgh in 1973,[18] Abramović explored elements of ritual and gesture. Making use of ten knives and two tape recorders, the artist played the Russian game, in which rhythmic knife jabs are aimed between the splayed fingers of one's hand, the title of the piece getting its name from the number of knives used. Each time she cut herself, she would pick up a new knife from the row of ten she had set up, and record the operation. After cutting herself ten times, she replayed the tape, listened to the sounds, and tried to repeat the same movements, attempting to replicate the mistakes, merging past and present. She set out to explore the physical and mental limitations of the body – the pain and the sounds of the stabbing; the double sounds from the history and the replication. With this piece, Abramović began to consider the state of consciousness of the performer. "Once you enter into the performance state you can push your body to do things you absolutely could never normally do."[19]

Rhythm 5, 1974

[edit]In this performance, Abramović sought to re-evoke the energy of extreme bodily pain, using a large petroleum-drenched star, which the artist lit on fire at the start of the performance. Standing outside the star, Abramović cut her nails, toenails, and hair. When finished with each, she threw the clippings into the flames, creating a burst of light each time. Burning the communist five-pointed star or pentagram represented a physical and mental purification, while also addressing the political traditions of her past. In the final act of purification, Abramović leapt across the flames into the center of the large pentagram. At first, due to the light and smoke given off by the fire, the observing audience did not realize that the artist had lost consciousness from lack of oxygen inside the star. However, when the flames came very near to her body and she still remained inert, a doctor and others intervened and extricated her from the star.

Abramović later commented upon this experience: "I was very angry because I understood there is a physical limit. When you lose consciousness you can't be present, you can't perform."[20]

Rhythm 2, 1974

[edit]Prompted by her loss of consciousness during Rhythm 5, Abramović devised the two-part Rhythm 2 to incorporate a state of unconsciousness in a performance. She performed the work at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, in 1974. In Part I, which had a duration of 50 minutes, she ingested a medication she describes as 'given to patients who suffer from catatonia, to force them to change the positions of their bodies.' The medication caused her muscles to contract violently, and she lost complete control over her body while remaining aware of what was going on. After a ten-minute break, she took a second medication 'given to schizophrenic patients with violent behavior disorders to calm them down.' The performance ended after five hours when the medication wore off.[21][22][23]

Rhythm 4, 1974

[edit]Rhythm 4 was performed at the Galleria Diagramma in Milan. In this piece, Abramović knelt alone and naked in a room with a high-power industrial fan. She approached the fan slowly, attempting to breathe in as much air as possible to push the limits of her lungs. Soon after she lost consciousness.[24]

Abramović's previous experience in Rhythm 5, when the audience interfered in the performance, led to her devising specific plans so that her loss of consciousness would not interrupt the performance before it was complete. Before the beginning of her performance, Abramović asked the cameraman to focus only on her face, disregarding the fan. This was so the audience would be oblivious to her unconscious state, and therefore unlikely to interfere. Ironically, after several minutes of Abramović's unconsciousness, the cameraman refused to continue and sent for help.[24]

Rhythm 0, 1974

[edit]To test the limits of the relationship between performer and audience, Abramović developed one of her most challenging and best-known performances. She assigned a passive role to herself, with the public being the force that would act on her. Abramović placed on a table 72 objects that people were allowed to use in any way that they chose; a sign informed them that they held no responsibility for any of their actions. Some of the objects could give pleasure, while others could be wielded to inflict pain, or to harm her. Among them were a rose, a feather, honey, a whip, olive oil, scissors, a scalpel, a gun and a single bullet. For six hours the artist allowed audience members to manipulate her body and actions without consequences. This tested how vulnerable and aggressive human subjects could be when actions have no social consequences.[3] At first the audience did not do much and was extremely passive. However, as the realization began to set in that there was no limit to their actions, the piece became brutal. By the end of the performance, her body was stripped, attacked, and devalued into an image that Abramović described as the "Madonna, mother, and whore."[3] As Abramović described it later: "What I learned was that ... if you leave it up to the audience, they can kill you. ... I felt really violated: they cut up my clothes, stuck rose thorns in my stomach, one person aimed the gun at my head, and another took it away. It created an aggressive atmosphere. After exactly 6 hours, as planned, I stood up and started walking toward the audience. Everyone ran away, to escape an actual confrontation."[25]

In her works, Abramović defines her identity in contradistinction to that of spectators; however, more importantly, by blurring the roles of each party, the identity and nature of humans individually and collectively also become less clear. By doing so, the individual experience morphs into a collective one and truths are revealed.[3] Abramović's art also represents the objectification of the female body, as she remains passive and allows spectators to do as they please to her; the audience pushes the limits of what might be considered acceptable. By presenting her body as an object, she explores the limits of danger and exhaustion a human can endure.[3]

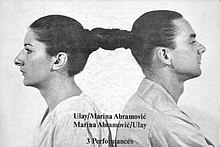

Works with Ulay (Uwe Laysiepen)

[edit]

In 1976, after moving to Amsterdam, Abramović met the West German performance artist Uwe Laysiepen, who went by the single name Ulay. They began living and performing together that year. When Abramović and Ulay began their collaboration,[15] the main concepts they explored were the ego and artistic identity. They created "relation works" characterized by constant movement, change, process and "art vital".[26] This was the beginning of a decade of influential collaborative work. Each performer was interested in the traditions of their cultural heritage and the individual's desire for ritual. Consequently, they decided to form a collective being called "The Other", and spoke of themselves as parts of a "two-headed body".[27] They dressed and behaved like twins and created a relationship of complete trust. As they defined this phantom identity, their individual identities became less defined. In an analysis of phantom artistic identities, Charles Green has noted that this allowed a deeper understanding of the artist as performer, since it revealed a way of "having the artistic self made available for self-scrutiny".[28]

The work of Abramović and Ulay tested the physical limits of the body and explored male and female principles, psychic energy, transcendental meditation, and nonverbal communication.[26] While some critics have explored the idea of a hermaphroditic state of being as a feminist statement, Abramović herself rejects this analysis. Her body studies, she insists, have always been concerned primarily with the body as the unit of an individual, a tendency she traces to her parents' military pasts. Rather than concerning themselves with gender ideologies, Abramović/Ulay explored extreme states of consciousness and their relationship to architectural space. They devised a series of works in which their bodies created additional spaces for audience interaction. In discussing this phase of her performance history, she has said: "The main problem in this relationship was what to do with the two artists' egos. I had to find out how to put my ego down, as did he, to create something like a hermaphroditic state of being that we called the death self."[29]

- In Relation in Space (1976) they ran into each other repeatedly for an hour – mixing male and female energy into the third component called "that self".[15]

- Relation in Movement (1977) had the pair driving their car inside of a museum for 365 laps; a black liquid oozed from the car, forming a kind of sculpture, each lap representing a year. (After 365 laps the idea was that they entered the New Millennium.)

- In Relation in Time (1977) they sat back to back, tied together by their ponytails for sixteen hours. They then allowed the public to enter the room to see if they could use the energy of the public to push their limits even further.[30]

- To create Breathing In/Breathing Out the two artists devised a piece in which they connected their mouths and took in each other's exhaled breaths until they had used up all of the available oxygen. Nineteen minutes after the beginning of the performance they pulled away from each other, their lungs having filled with carbon dioxide. This personal piece explored the idea of an individual's ability to absorb the life of another person, exchanging and destroying it.

- In Imponderabilia (1977, reenacted in 2010) two performers of opposite sexes, both completely nude, stand in a narrow doorway. The public must squeeze between them in order to pass, and in doing so choose which one of them to face.[15]

- In AAA-AAA (1978) the two artists stood opposite each other and made long sounds with their mouths open. They gradually moved closer and closer, until they were eventually yelling directly into each other's mouths.[30] This piece demonstrated their interest in endurance and duration.[30]

- In 1980, they performed Rest Energy, in an art exhibition in Amsterdam, where both balanced each other on opposite sides of a drawn bow and arrow, with the arrow pointed at Abramović's heart. With almost no effort, Ulay could easily kill Abramović with one finger. This was intended to represent the power advantage men have over women in society. In addition, the handle of the bow is held by Abramović and is pointed at herself. The handle of the bow is the most significant part of a bow. This would be a whole different piece if it were Ulay aiming a bow at Abramović, but by having her hold the bow, even while her life is subject to his will, she supports him.[15][31]

Between 1981 and 1987, the pair performed Nightsea Crossing in twenty-two performances. They sat silently across from each other in chairs for seven hours a day.[30]

In 1988, after several years of tense relations, Abramović and Ulay decided to make a spiritual journey that would end their relationship. They each walked the Great Wall of China, in a piece called Lovers, starting from the two opposite ends and meeting in the middle. As Abramović described it: "That walk became a complete personal drama. Ulay started from the Gobi Desert and I from the Yellow Sea. After each of us walked 2500 km, we met in the middle and said good-bye."[32] She has said that she conceived this walk in a dream, and it provided what she thought was an appropriate, romantic ending to a relationship full of mysticism, energy, and attraction. She later described the process: "We needed a certain form of ending, after this huge distance walking towards each other. It is very human. It is in a way more dramatic, more like a film ending ... Because in the end, you are really alone, whatever you do."[32] She reported that during her walk she was reinterpreting her connection to the physical world and to nature. She felt that the metals in the ground influenced her mood and state of being; she also pondered the Chinese myths in which the Great Wall has been described as a "dragon of energy". It took the couple eight years to acquire permission from the Chinese government to perform the work, by which time their relationship had completely dissolved.

At her 2010 MoMA retrospective, Abramović performed The Artist Is Present, in which she shared a period of silence with each stranger who sat in front of her. Although "they met and talked the morning of the opening",[33] Abramović had a deeply emotional reaction to Ulay when he arrived at her performance, reaching out to him across the table between them; the video of the event went viral.[34]

In November 2015, Ulay took Abramović to court, claiming she had paid him insufficient royalties according to the terms of a 1999 contract covering sales of their joint works[35][36] and a year later, in September 2016, Abramović was ordered to pay Ulay €250,000. In its ruling, the court in Amsterdam found that Ulay was entitled to royalties of 20% net on the sales of their works, as specified in the original 1999 contract, and ordered Abramović to backdate royalties of more than €250,000, as well as more than €23,000 in legal costs.[37] Additionally, she was ordered to credit all works created between 1976 and 1980 as "Ulay/Abramović" and all works created between 1981 and 1988 as "Abramović/Ulay".

Cleaning the Mirror, 1995

[edit]

Cleaning the Mirror consisted of five monitors playing footage in which Abramović scrubs a grimy human skeleton in her lap. She vigorously brushes the different parts of the skeleton with soapy water. Each monitor is dedicated to one part of the skeleton: the head, the pelvis, the ribs, the hands, and the feet. Each video is filmed with its own sound, creating an overlap. As the skeleton becomes cleaner, Abramović becomes covered in the grayish dirt that was once covering the skeleton. This three-hour performance is filled with metaphors of the Tibetan death rites that prepare disciples to become one with their own mortality. The piece was composed of three parts. Cleaning the Mirror #1, lasting three hours, was performed at the Museum of Modern Art. Cleaning the Mirror #2 lasts 90 minutes and was performed at Oxford University. Cleaning the Mirror #3 was performed at Pitt Rivers Museum over five hours.[38]

Spirit Cooking, 1996

[edit]Abramović worked with Jacob Samuel to produce a cookbook of "aphrodisiac recipes" called Spirit Cooking in 1996. These "recipes" were meant to be "evocative instructions for actions or for thoughts".[39] For example, one of the recipes calls for "13,000 grams of jealousy", while another says to "mix fresh breast milk with fresh sperm milk."[40] The work was inspired by the popular belief that ghosts feed off intangible things like light, sound, and emotions.[41]

In 1997, Abramović created a multimedia Spirit Cooking installation. This was originally installed in the Zerynthia Associazione per l'Arte Contemporanea in Rome, Italy, and included white gallery walls with "enigmatically violent recipe instructions" painted in pig's blood.[42] According to Alexxa Gotthardt, the work is "a comment on humanity's reliance on ritual to organize and legitimize our lives and contain our bodies".[43]

Abramovic also published a Spirit Cooking cookbook, containing comico-mystical, self-help instructions that are meant to be poetry. Spirit Cooking later evolved into a form of dinner party entertainment that Abramovic occasionally lays on for collectors, donors, and friends.[44]

Balkan Baroque, 1997

[edit]In this piece, Abramović vigorously scrubbed thousands of bloody cow bones over a period of four days, a reference to the ethnic cleansing that had taken place in the Balkans during the 1990s. This performance piece earned Abramović the Golden Lion award at the Venice Biennale.[45]

Abramović created Balkan Baroque as a response to the war in Bosnia. She remembers other artists reacting immediately, creating work and protesting about the effects and horrors of the war. Abramović could not bring herself to create work on the matter so soon, as it hit too close to home for her. Eventually, Abramović returned to Belgrade, where she interviewed her mother, her father, and a rat-catcher. She then incorporated these interviews into her piece, as well as clips of the hands of her father holding a pistol and her mother's empty hands and later, her crossed hands. Abramović is dressed as a doctor recounting the story of the rat-catcher. While the clips are playing, Abramović sits among a large pile of bones and tries to wash them.

The performance occurred in Venice in 1997. Abramović remembered the horrible smell – for it was extremely hot in Venice that summer – and that worms emerged from the bones.[46] She has explained that the idea of scrubbing the bones clean and trying to remove the blood, is impossible. The point Abramović was trying to make is that blood can't be washed from bones and hands, just as the war couldn't be cleansed of shame. She wanted to allow the images from the performance to speak for not only the war in Bosnia, but for any war, anywhere in the world.[46]

Seven Easy Pieces, 2005

[edit]

Beginning on November 9, 2005, Abramović presented Seven Easy Pieces commissioned by Performa, at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. On seven consecutive nights for seven hours she recreated the works of five artists first performed in the 1960s and 1970s, in addition to re-performing her own Thomas Lips and introducing a new performance on the last night. The performances were arduous, requiring both the physical and the mental concentration of the artist. Included in Abramović's performances were recreations of Gina Pane's The Conditioning, which required lying on a bed frame suspended over a grid of lit candles, and of Vito Acconci's 1972 performance in which the artist masturbated under the floorboards of a gallery as visitors walked overhead. It is argued that Abramović re-performed these works as a series of homages to the past, though many of the performances were altered from the originals.[47] All seven performances were dedicated to Abramović's late friend Susan Sontag.

A full list of the works performed is as follows:

- Bruce Nauman's Body Pressure (1974)

- Vito Acconci's Seedbed (1972)

- Valie Export's Action Pants: Genital Panic (1969)

- Gina Pane's The Conditioning (1973)

- Joseph Beuys's How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965)

- Abramović's own Thomas Lips (1975)

- Abramović's own Entering the Other Side (2005)

The Artist Is Present: March–May 2010

[edit]

From March 14 to May 31, 2010, the Museum of Modern Art held a major retrospective and performance recreation of Abramović's work, the biggest exhibition of performance art in MoMA's history, curated by Klaus Biesenbach.[48] Biesenbach also provided the title for the performance, which referred to the fact that during the entire performance "the artist would be right there in the gallery or the museum."[49]

During the run of the exhibition, Abramović performed The Artist Is Present,[50] a 736-hour and 30-minute static, silent piece, in which she sat immobile in the museum's atrium while spectators were invited to take turns sitting opposite her.[51] Ulay made a surprise appearance at the opening night of the show.[52]

Abramović sat in a rectangle marked with tape on the floor of the second floor atrium of the MoMA; theater lights shone on her sitting in a chair and a chair opposite her.[53] Visitors waiting in line were invited to sit individually across from the artist while she maintained eye contact with them. Visitors began crowding the atrium within days of the show opening, some gathering before the exhibit opened each morning to get a better place in line. Most visitors sat with the artist for five minutes or less, a few sat with her for an entire day.[54] The line attracted no attention from museum security until the last day of the exhibition, when a visitor vomited in line and another began to disrobe. Tensions among visitors in line could have arisen from the realization that the longer the earlier visitors spent with Abramović, the less chance that those further back in line would be able to sit with her. Due to the strenuous nature of sitting for hours at a time, art-enthusiasts have wondered whether Abramović wore an adult diaper in order to eliminate the need for bathroom breaks. Others have highlighted the movements she made in between sitters as a focus of analysis, as the only variations in the artist between sitters were when she would cry if a sitter cried and her moment of physical contact with Ulay, one of the earliest visitors to the exhibition. Abramović sat across from 1,545 sitters, including Klaus Biesenbach, James Franco, Lou Reed, Alan Rickman, Jemima Kirke, Jennifer Carpenter, and Björk; sitters were asked not to touch or speak to her. By the end of the exhibit, hundreds of visitors were lining up outside the museum overnight to secure a spot in line the next morning. Abramović concluded the performance by slipping from the chair where she was seated and rising to a cheering crowd more than ten people deep.

A support group for the "sitters", "Sitting with Marina", was established on Facebook,[55] as was the blog "Marina Abramović made me cry".[56] The Italian photographer Marco Anelli took portraits of every person who sat opposite Abramović, which were published on Flickr,[57] compiled in a book[58] and featured in an exhibition at the Danziger Gallery in New York.[59]

Abramović said the show changed her life "completely – every possible element, every physical emotion". After Lady Gaga saw the show and publicized it, Abramović found a new audience: "So the kids from 12 and 14 years old to about 18, the public who normally don't go to the museum, who don't give a shit about performance art or don't even know what it is, started coming because of Lady Gaga. And they saw the show and then they started coming back. And that's how I get a whole new audience."[60] In September 2011, a video game version of Abramović's performance was released by Pippin Barr.[61] In 2013, Dale Eisinger of Complex ranked The Artist Is Present ninth (along with Rhythm 0) in his list of the greatest performance art works.[62]

Her performance inspired Australian novelist Heather Rose to write The Museum of Modern Love[63] and she subsequently launched the US edition of the book at the Museum of Modern Art in 2018.[64]

Other

[edit]

In 2009, Abramović was featured in Chiara Clemente's documentary Our City Dreams and a book of the same name. The five featured artists – also including Swoon, Ghada Amer, Kiki Smith, and Nancy Spero – "each possess a passion for making work that is inseparable from their devotion to New York", according to the publisher.[65] Abramović is also the subject of an independent documentary film entitled Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present, which is based on her life and performance at her retrospective "The Artist Is Present" at the Museum of Modern Art in 2010. The film was broadcast in the United States on HBO[66] and won a Peabody Award in 2012.[67] In January 2011, Abramović was on the cover of Serbian ELLE, photographed by Dušan Reljin. Kim Stanley Robinson's science fiction novel 2312 mentions a style of performance art pieces known as "abramovics".

A world premiere installation by Abramović was featured at Toronto's Trinity Bellwoods Park as part of the Luminato Festival in June 2013. Abramović is also co-creator, along with Robert Wilson of the theatrical production The Life and Death of Marina Abramović, which had its North American premiere at the festival,[citation needed] and at the Park Avenue Armory in December.[68]

In 2007 Abramović created the Marina Abramović Institute (MAI), a nonprofit foundation for performance art, in a 33,000 square-foot space in Hudson, New York.[69] She also founded a performance institute in San Francisco.[26] She is a patron of the London-based Live Art Development Agency.[70]

In June 2014 she presented a new piece at London's Serpentine Gallery called 512 Hours.[71] In the Sean Kelly Gallery-hosted Generator, (December 6, 2014)[72] participants are blindfolded and wear noise-canceling headphones in an exploration of nothingness.

In celebration of her 70th birthday on November 30, 2016, Abramović took over the Guggenheim museum (eleven years after her previous installation there) for her birthday party entitled "Marina 70". Part one of the evening, titled "Silence," lasted 70 minutes, ending with the crash of a gong struck by the artist. Then came the more conventional part two: "Entertainment", during which Abramović took to the stage to make a speech before watching English singer and visual artist ANOHNI perform the song "My Way" while wearing a large black hood.[73]

In March 2015, Abramović presented a TED talk titled, "An art made of trust, vulnerability and connection".[74]

In 2019, IFC's mockumentary show Documentary Now! parodied Abramović's work and the documentary film Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present. The show's episode, entitled "Waiting for the Artist", starred Cate Blanchett as Isabella Barta (Abramović) and Fred Armisen as Dimo (Ulay).

Originally set to open on September 26, 2020, her first major exhibition in the UK at the Royal Academy of Arts was rescheduled for autumn 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the Academy, the exhibition would "bring together works spanning her 50-year career, along with new works conceived especially for these galleries. As Abramović approaches her mid-70s, her new work reflects on changes to the artist's body, and explores her perception of the transition between life and death."[75] On reviewing this exhibition Tabish Khan, writing for Culture Whisper, described it thus: “It’s intense, it’s discomfiting, it’s memorable, and it’s performance art at its finest".[76]

In 2021, she dedicated a monument, entitled, Crystal wall of crying, at the site of a Holocaust massacre in Ukraine and which is memorialized through the Babi Yar memorials.[77]

In 2022, she condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[78]

In 2023, she was the first woman in 255 years to be invited to give a solo show in the main galleries of the Royal Academy.[79]

Unfulfilled proposals

[edit]Abramović had proposed some solo performances during her career that never were performed. One such proposal was titled "Come to Wash with Me". This performance would take place in a gallery space that was to be transformed into a laundry with sinks placed all around the walls of the gallery. The public would enter the space and be asked to take off all of their clothes and give them to Abramović. The individuals would then wait around as she would wash, dry and iron their clothes for them, and once she was done, she would give them back their clothing, and they could get dressed and then leave. She proposed this in 1969 for the Galerija Doma Omladine in Belgrade. The proposal was refused.

In 1970 she proposed a similar idea to the same gallery that was also refused. The piece was untitled. Abramović would stand in front of the public dressed in her regular clothing. Present on the side of the stage was a clothes rack adorned with clothing that her mother wanted her to wear. She would take the clothing one by one and change into them, then stand to face the public for a while. "From the right pocket of my skirt I take a gun. From the left pocket of my skirt I take a bullet. I put the bullet into the chamber and turn it. I place the gun to my temple. I pull the trigger." The performance had two possible outcomes.[80]

The list of Mother's clothes included:

- Heavy brown pin for the hair

- White cotton blouse with red dots

- Light pink bra – 2 sizes too big

- Dark pink heavy flannel slip – three sizes too big

- Dark blue skirt – mid-calf

- Skin color heavy synthetic stockings

- Heavy orthopedic shoes with laces

Films

[edit]Abramović directed a segment, Balkan Erotic Epic, in Destricted, a compilation of erotic films made in 2006.[81] In 2008 she directed a segment Dangerous Games in another film compilation Stories on Human Rights.[82] She also acted in a five-minute short film Antony and the Johnsons: Cut the World.[83]

Marina Abramović Institute

[edit]The Marina Abramović Institute (MAI) is a performance art organization with a focus on performance, works of long duration, and the use of the "Abramovic Method".[84]

In its early phases, it was a proposed multi-functional museum space in Hudson, New York.[85] Abramović purchased the site for the institute in 2007.[86] Located in Hudson, New York, the building was built in 1933 and has been used as a theater and community tennis center.[87] The building was to be renovated according to a design by Rem Koolhaas and Shohei Shigematsu of OMA.[88] The early design phase of this project was funded by a Kickstarter campaign.[89] It was funded by more than 4,000 contributors, including Lady Gaga and Jay-Z.[90][91][92][93] The building project was canceled in October 2017 due to its excessive cost.[94]

The institute continues to operate as a traveling organization. To date, MAI has partnered with many institutions and artists internationally, traveling to Brazil, Greece, and Turkey.[95][96]

Collaborations

[edit]In her youth, she was a performer in one of Hermann Nitsch's performances which were part of the Viennese actionism.

Abramović maintains a friendship with actor James Franco, who interviewed her for The Wall Street Journal in 2009.[97] Franco visited her during The Artist Is Present in 2010,[98] and the two also attended the 2012 Met Gala together.[99]

In July 2013, Abramović worked with Lady Gaga on the pop singer's third album Artpop. Gaga's work with Abramović, as well as artists Jeff Koons and Robert Wilson, was displayed at an event titled "ArtRave" on November 10.[100] Furthermore, both have collaborated on projects supporting the Marina Abramović Institute, including Gaga's participation in an 'Abramović Method' video and a nonstop reading of Stanisław Lem's sci-fi novel Solaris.[101]

Also that month, Jay-Z showcased an Abramović-inspired piece at Pace Gallery in New York City. He performed his art-inspired track "Picasso Baby" for six straight hours.[102] During the performance, Abramović and several figures in the art world were invited to dance with him standing face to face.[103] The footage was later turned into the music video for the aforementioned song. She allowed Jay-Z to adapt "The Artist Is Present" under the condition that he would donate to her institute. Abramović stated that Jay-Z did not live up to his end of the deal, describing the performance as a "one-way transaction".[104] However, two years later in 2015, Abramović publicly issued an apology stating she was never informed of Jay-Z's sizable donation.[105]

Controversies

[edit]Abramović sparked controversy in August 2016 when passages from an early draft of her memoir were released, in which—based on notes from her 1979 initial encounter with Aboriginal Australians—she compared them to dinosaurs and observed that "they have big torsos (just one bad result of their encounter with Western civilization is a high sugar diet that bloats their bodies) and sticklike legs". She responded to the controversy on Facebook, writing, "I have the greatest respect for the Aborigine people, to whom I owe everything."[106]

Among the Podesta emails was a message from Abramović to Podesta's brother discussing an invitation to a spirit cooking, which was interpreted by conspiracy theorists such as Alex Jones as an invitation to a satanic ritual, and was presented by Jones and others as proof that Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton had links to the occult.[107] In a 2013 Reddit Q&A, in response to a question about occult in contemporary art, she said: "Everything depends on which context you are doing what you are doing. If you are doing the occult magic in the context of art or in a gallery, then it is the art. If you are doing it in different context, in spiritual circles or private house or on TV shows, it is not art. The intention, the context for what is made, and where it is made defines what art is or not".[108]

On April 10, 2020, Microsoft released a promotional video for HoloLens 2 which featured Abramović. However, due to accusations by right-wing conspiracy theorists of her having ties to Satanism, Microsoft eventually pulled the advertisement.[109] Abramović responded to the criticism, appealing to people to stop harassing her, arguing that her performances are just the art that she has been doing for the last 50 years.[110]

Personal life

[edit]Abramović claims she feels "neither like a Serb, nor a Montenegrin", but an ex-Yugoslav.[111] "When people ask me where I am from," she says, "I never say Serbia. I always say I come from a country that no longer exists."[6]

Abramović has had three abortions during her life, and has said that having children would have been a "disaster" for her work.[112][113]

Sculptor Nikola Pešić says that Abramović has a lifelong interest in esotericism and Spiritualism.[114]

Awards

[edit]- Golden Lion, XLVII Venice Biennale, 1997[115]

- Niedersächsischer Kunstpreis, 2002[116]

- New York Dance and Performance Awards (The Bessies), 2002[116]

- International Association of Art Critics, Best Show in a Commercial Gallery Award, 2003

- Austrian Decoration for Science and Art (2008)[117]

- Honorary Doctorate of Arts, University of Plymouth UK, September 25, 2009[118]

- Honorary Royal Academician (HonRA), September 27, 2011[119]

- Cultural Leadership Award, American Federation of Arts, October 26, 2011[120]

- Honorary Doctorate of Arts, Instituto Superior de Arte, Cuba, May 14, 2012[121]

- July 13' Lifetime Achievement Awards, Podgorica, Montenegro, October 1, 2012[120]

- The Karić brothers award (category art and culture), 2012

- Berliner Bär (B.Z.-Kulturpreis) (2012; not to be confused with the Silver and Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival; a cultural award of the German tabloid BZ)[citation needed]

- Shortlisted for the European Cultural Centre Art Award in 2017.

- Golden Medal for Merits, Republic of Serbia, 2021[122]

- Princess of Asturias Award in the category of Arts, 2021.[123]

- Sonning Prize, 2023[124]

Bibliography

[edit]Books by Abramović and collaborators

[edit]- Cleaning the House, artist Abramović, author Abramović (Wiley, 1995) ISBN 978-1-85490-399-0

- Artist Body: Performances 1969–1998, artist, Abramović; authors Abramović, Toni Stooss, Thomas McEvilley, Bojana Pejic, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Chrissie Iles, Jan Avgikos, Thomas Wulffen, Velimir Abramović; English ed. (Charta, 1998) ISBN 978-88-8158-175-7.

- The Bridge / El Puente, artist Abramović, authors Abramović, Pablo J. Rico, Thomas Wulffen (Charta, 1998) ISBN 978-84-482-1857-7.

- Performing Body, artist Abramović, authors Abramović, Dobrila Denegri (Charta, 1998) ISBN 978-88-8158-160-3.

- Public Body: Installations and Objects 1965–2001, artist Abramović, authors Celant, Germano, Abramović (Charta, 2001) ISBN 978-88-8158-295-2.

- Marina Abramović, fifteen artists, Fondazione Ratti; coauthors Abramović, Anna Daneri, Giacinto Di Pietrantonio, Lóránd Hegyi, Societas Raffaello Sanzio, Angela Vettese (Charta, 2002) ISBN 978-88-8158-365-2.

- Student Body, artist Abramović, vari; authors Abramović, Miguel Fernandez-Cid, students; (Charta, 2002) ISBN 978-88-8158-449-9.

- The House with the Ocean View, artist Abramović; authors Abramović, Sean Kelly, Thomas McEvilley, Cindy Carr, Chrissie Iles, RosaLee Goldberg, Peggy Phelan (Charta, 2004) ISBN 978-88-8158-436-9; the 2002 piece of the same name, in which Abramović lived on three open platforms in a gallery with only water for 12 days, was reenacted in Sex and the City in the HBO series' sixth season.[125]

- Marina Abramović: The Biography of Biographies, artist Abramović; coauthors Abramović, Michael Laub, Monique Veaute, Fabrizio Grifasi (Charta, 2004) ISBN 978-88-8158-495-6.

- Balkan Epic, (Skira, 2006).

- Seven Easy Pieces, artist, Abramović; authors Nancy Spector, Erika Fischer-Lichte, Sandra Umathum, Abramović; (Charta, 2007). ISBN 978-88-8158-626-4.

- Marina Abramović, artist Abramović; authors Kristine Stiles, Klaus Biesenbach, Chrissie Iles, Abramović; (Phaidon, 2008). ISBN 978-0-7148-4802-0.

- When Marina Abramović Dies: A Biography. Author James Westcott. (MIT, 2010). ISBN 978-0-262-23262-3.

- Walk Through Walls: A Memoir, author Abramović (Crown Archetype, 2016). ISBN 978-1-101-90504-3.

Films by Abramović and collaborators

[edit]- Balkan Baroque, (Pierre Coulibeuf, 1999)

- Balkan Erotic Epic, as producer and director, Destricted (Offhollywood Digital, 2006)

References

[edit]- ^ Roizman, Ilene (November 5, 2018). "Marina Abramovic pushes the limits of performance art". Scene 360. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Christiane., Weidemann (2008). 50 women artists you should know. Larass, Petra., Klier, Melanie, 1970–. Munich: Prestel. ISBN 9783791339566. OCLC 195744889.

- ^ a b c d e Demaria, Cristina (August 2004). "The Performative Body of Marina Abramovic". European Journal of Women's Studies. 11 (3): 295. doi:10.1177/1350506804044464. S2CID 145363453.

- ^ "MAI". Marina Abramovic Institute. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ "MAI: marina abramovic institute". designboom | architecture & design magazine. August 23, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f O'Hagan, Sean (October 2, 2010). "Interview: Marina Abramović". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ^ Thurman, Judith (March 8, 2010). "Walking Through Walls". The New Yorker. p. 24.

- ^ Stated on "The Eye of the Beholder", Season 5, Episode 9 of Finding Your Roots, April 2, 2019.

- ^ "Marina Abramović". Lacan.com. Archived from the original on September 17, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Marina Abramović: The grandmother of performance art on her 'brand'". The Independent. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ^ "Biography of Marina Abramović – Moderna Museet i Stockholm". Moderna Museet i Stockholm. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Quoted in Thomas McEvilley, "Stages of Energy: Performance Art Ground Zero?" in Abramović, Artist Body, [Charta, 1998].

- ^ a b Ouzounian, Richard (May 31, 2013). "Famous for The Artist Is Present, Abramovic will share The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic and more with Toronto June 14 to 23". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ^ "Marina Abramovic". Moderna Museet. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Marina Abramović". Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ "Biografie von Marina Abramović – Marina Abramović auf artnet". www.artnet.de. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ "Marina Abramović CV | Artists | Lisson Gallery". www.lissongallery.com. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ "Media Art Net – Abramovic, Marina: Rhythm 10". September 20, 2021.

- ^ Kaplan, 9

- ^ Daneri, 29

- ^ Dezeuze, Anna; Ward, Frazer (2012). "Marina Abramovic: Approaching zero". The "Do-It-Yourself" Artwork: Participation from Fluxus to New Media. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 132–144. ISBN 978-0-7190-8747-9.

- ^ Pejic, Bojana; Abramovic, Marina; McEvilley, Thomas; Stoos, Toni (July 2, 1998). Marina Abramovic: Artist Body. Milano: Charta. ISBN 978-88-8158-175-7.

- ^ Danto, Arthur; Iles, Chrissie; Abramovic, Marina (April 30, 2010). Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present. Klaus Biesenbach (ed.) (Second Printing ed.). New York: The Museum of Modern Art, New York. ISBN 978-0-87070-747-6.

- ^ a b "Rhythm Series – Marina Abramović". Blogs.uoregon.edu. February 10, 2015. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "Audience To Be". The Theatre Times. February 11, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c Stiles, Kristine (2012). Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art (second ed.). University of California Press. pp. 808–809.

- ^ Quoted in Green, 37

- ^ Green, 41

- ^ Kaplan, 14

- ^ a b c d "Ulay/Abramović – Marina Abramović". Blogs.uoregon.edu. February 12, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ "Documenting the performance art of Marina Abramović in pictures | Art | Agenda". Phaidon. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ a b "Lovers Abramović & Ulay Walk the Length of the Great Wall of China from opposite ends, Meet in the Middle and BreakUp – Kickass Trips". January 14, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Klaus Biesenbach on the AbramovicUlay Reunion". Blouin Artinfo. March 16, 2010. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018.

- ^ "Video of Marina Abramović and Ulay at MoMA retrospective". YouTube. December 15, 2012. Archived from the original on November 2, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Esther Addley and Noah Charney. "Marina Abramović sued by former lover and collaborator Ulay | Art and design". The Guardian. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ Charney, Noah. "Ulay v Marina: how art's power couple went to war | Art and design". The Guardian. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ Quinn, Ben; Charney, Noah (September 21, 2016). "Marina Abramović ex-partner Ulay claims victory in case of joint work". The Guardian. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ^ Abramovic, M., & von Drathen, D. (2002). Marina Abramovic. Fondazione Antonio Ratti.

- ^ "Marina Abramović. Spirit Cooking. 1996". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ Ohlheiser (November 4, 2016). "No, John Podesta didn't drink bodily fluids at a secret Satanist dinner". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ Sels, Nadia (2011). "From theatre to time capsule: art at Jan Fabre's Troubleyn/Laboratory" (PDF). ISEL Magazine. pp. 77–83.

- ^ Lacis, Indra K. (May 2014). "Fame, Celebrity and Performance: Marina Abramović—Contemporary Art Star". Case Western Reserve University. pp. 117–118. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ Gotthardt, Alexxa (December 22, 2016). "The Story behind the Marina Abramović Performance That Contributed to Pizzagate". Artsy. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- ^ The MIT Press (June 28, 2017). "Marina Abramovic's Spirit Cooking". The MIT Press.

- ^ Lacis, Indra K. (2014). Fame, Celebrity and Performance: Marina Abramović--Contemporary Art Star (Thesis). Case Western Reserve University. Archived from the original on April 4, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "Marina Abramović. Balkan Baroque. 1997". Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present. The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Marina Abramović, BLOUINARTINFO, November 9, 2005, retrieved April 23, 2008

- ^ Kino, Carol (March 10, 2010). "A Rebel Form Gains Favor. Fights Ensue.", The New York Times. Retrieved April 16, 2010.

- ^ Abramović, Marina (2016). Walk Through Walls. New York: Crown Archetype. p. 298. ISBN 978-1-101-90504-3.

- ^ Abramović, Marina (2016). Walk Through Walls. New York: Crown Archetype. pp. 298–299. ISBN 978-1-101-90504-3.

- ^ Arboleda, Yazmany (May 28, 2010). "Bringing Marina Flowers". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on June 25, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ "Klaus Biesenbach on the AbramovicUlay Reunion". Blouinartinfo. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ Marcus, S. (2015). "Celebrity 2.0: The Case of Marina Abramovi". Public Culture. 27 (1 75): 21–52. doi:10.1215/08992363-2798331. ISSN 0899-2363.

- ^ de Yampert, Rick (June 11, 2010). "Is it art? Sit down and think about it". Daytona Beach News-Journal, The (FL).

- ^ Elmhurst, Sophie (July 16, 2014). "Marina Abramovic: The Power of One". Harpers Bazaar UK. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "Marina Abramović Made Me Cry".

- ^ "Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present—Portraits". Flickr. March 28, 2010.

- ^ Anelli, Marco; Abramović, Marina; Biesenbach, Klaus; Iles, Chrissie (2012). Marco Anelli: Portraits in the Presence of Marina Abramovic: Marina Abramovic, Klaus Biesenbach, Chrissie Iles, Marco Anelli: 9788862082495: Amazon.com: Books. Distributed Art Pub Incorporated. ISBN 978-8862082495.

- ^ "Marco Anelli – Exhibitions". Danziger Gallery. October 27, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ "I've Always Been A Soldier", The Talks. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Gray, Rosie (September 16, 2011). "Pippin Barr, Man Behind the Marina Abramovic Video Game, Weighs in on His Creation. Archived May 30, 2015, at the Wayback Machine", The Village Voice'. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ Eisinger, Dale (April 9, 2013). "The 25 Best Performance Art Pieces of All Time". Complex. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Convery, Stephanie (April 18, 2017). "Stella prize 2017: Heather Rose's The Museum of Modern Love wins award". The Guardian.

- ^ Rychter, Tacey (November 26, 2018). "An Artist Who Explores Emotional Pain Inspires a Novel That Does the Same". The New York Times. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ^ Clemente, Chiara, and Dodie Kazanjian, Our City Dreams, Charta webpage. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ Marina Abramović to be the subject of a movie, "MARINA" the film, 2010, archived from the original on February 9, 2010

- ^ 72nd Annual Peabody Awards, May 2013.

- ^ "'The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic' Opera Arrives At Armory In December". The Huffington Post. February 19, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (October 19, 2013). "For Her Next Piece, a Performance Artist Will Build an Institute". The New York Times.

- ^ "Live Art Development Agency". www.thisisliveart.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011.

- ^ Savage, Mark (June 11, 2014). "Marina Abramovic: Audience in tears at 'empty space' show". BBC News. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ "Generator Exhibition". Sean Kelly Gallery. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016.

- ^ "Marina Abramović Celebrates 70th Birthday". Artnet News. December 9, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "Marina Abramović: An art made of trust, vulnerability and connection | TED Talk". TED.com. November 30, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ "Marina Abramović | Exhibition". Royal Academy of Art. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Khan, Tabish. "Marina Abramovic, Royal Academy of Arts, review". Culture Whisper.

- ^ "Marina Abramovic has healed from her own art, now she's healing visitors to Babi Yar – Life & Culture". Haaretz.com. October 21, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ "Marina Abramovic: An artist for Ukraine – DW – 03/27/2022". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ Parkinson, Hannah Jane (September 29, 2023). "At long last, the female artist is present". The Guardian Weekly. p. 54.

- ^ Abramovic, Marina (1998). Marina Abramovic Artist Body. Milano: Charta. pp. 54–55. ISBN 8881581752.

- ^ "Destricted". IMDB.

- ^ "Stories on Human Rights". IMDB.

- ^ "Antony and the Johnsons : Cut the World". IMDB.

- ^ "MAI". Marina Abramovic Institute. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Ryzik, Melena (May 6, 2012). "Special Chairs and Lots of Time: Marina Abramovic Plans Her New Center". The New York Times. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ "marina abramović launches kickstarter campaign for the marina abramović institute by OMA". designboom. August 23, 2013.

- ^ Genocchio, Benjamin (April 6, 2008). "Seeking to Create a Timeless Space". The New York Times. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ Ebony, David (August 13, 2012). "Marina Abramovic's New Hudson River School". Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ Sulcas, Roslyn (August 26, 2013). "Marina Abramovic Kickstarter Campaign Passes Goal". Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ Gibsone, Harriet. "Lady Gaga and Jay-Z help Marina Abramovic reach Kickstarter goal". The Guardian. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ Cutter, Kimberly (October 10, 2013). "Marina Abramović Saves The World". Harper's Bazaar. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ Farokhmanesh, Megan (October 26, 2013). "Digital Marina Abramovic Institute provides a virtual tour". Polygon. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Jason. "Pippin Barr wants you to feel the pain for a longer Duration". Archived from the original on January 17, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ^ Rogers, Pat (October 8, 2017). "Marina Abramovic Cancels Plan for Hudson Performance Place". Hamptons Art Hub. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ "The Art of Truth". static1.squarespace.com. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- ^ "Marina Abramovic Institute". Marina Abramovic Institute. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "James Franco, Marina Abramović Talk Performance Art, Eating Gold, And Dessert". The Huffington Post. May 11, 2010. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "James Franco Meets Marina Abramović At MoMA". The Huffington Post. May 10, 2010. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Busacca, Larry (May 7, 2012). "The Met Costume Institute Gala 2012". Omg.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "ARTPOP". Lady Gaga. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Gets Completely Naked to Support the Marina Abramovic Institute". E! Online UK. August 7, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Minsker, Evan (May 19, 2015). "Marina Abramovic Says 'Cruel' Jay Z 'Completely Used' Her for 'Picasso Baby' Stunt | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Steinhauer, Jillian (July 10, 2013). "Jay-Z Raps at Marina Abramović, or the Day Performance Art Died". Hyperallergic. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ "Marina Abramovic says Jay Z "just completely used" her". FACT Magazine: Music News, New Music. May 19, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Muller, Marissa. "Marina Abramović Has Issued An Apology To Jay Z". The FADER. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Gabriella Paiella (August 15, 2016). "Marina Abramovic Made Some Pretty Racist Statements in Her Memoir". New York. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ^ Lee, Benjamin (November 4, 2016). "Marina Abramović mention in Podesta emails sparks accusations of satanism". The Guardian. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ "r/IAmA – I am performance artist Marina Abramovic. Ask me anything". reddit. July 30, 2013.

- ^ Kinsella, Eileen (April 15, 2020). "Microsoft Just Pulled an Ad Featuring Marina Abramovic After Right-Wing Conspiracy Theorists Accused Her of Satanism". Artnet News. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ Marshall, Alex (April 21, 2020). "Marina Abramovic Just Wants Conspiracy Theorists to Let Her Be". The New York Times. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ "Marina Abramović: Nijesam ni Srpkinja, ni Crnogorka, ja sam eks-Jugoslovenka" [Marina Abramović: I'm neither a Serb, nor a Montenegrin, I am an ex-Yugoslav]. Cafe del Montenegro (in Montenegrin). July 27, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ "Marina Abramovic had three abortions because children would have been a 'disaster' for her art". The Independent. July 27, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ "Marina Abramović says having children would have been 'a disaster for my work'". The Guardian. July 26, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ Nikola Pešić, Marina Abramović, World Religions and Spirituality Project, January 15, 2017.

- ^ "La Biennale di Venezia – Awards since 1986". www.labiennale.org. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Phelan, Peggy. "Marina Abramovic: Witnessing Shadows". Theatre Journal. Vol. 56, Number 4. December 2004

- ^ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). p. 1879. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ^ "University of Plymouth unveils 2009 Honorary Degree Awards". My Science. September 8, 2009. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ "Marina Abramović | Artist | Royal Academy of Arts". Royal Academy of Arts. Archived from the original on August 21, 2023.

- ^ a b III, Everette Hatcher (January 8, 2015). "FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 41 Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (Featured artist is Marina Abramović)". The Daily Hatch. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Vladimir. "Poemes de Jovan Dučić / Песме Јована Дучића". Serbica Americana. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ "СВЕТОГРЂЕ! Вучић на Сретење доделио орден Марини Абрамовић! Ево свих 170 имена (СПИСАК)". pravda.rs. May 19, 2015. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ "Marina Abramović, Princess of Asturias Award for the Arts". The Princess of Asturias Foundation. May 12, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ "Conceptual performance artist is awarded the Sonning Prize". January 19, 2023. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ "Gatecrasher" (staff writer), "Kim Cattrall and performance artist Marina Abramovic are unlikely 'Sex and the City' buddies", New York Daily News, April 18, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Hear the artist speak about her work MoMA Audio: Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present

- Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present at MoMA

- Marina Abramović: 512 Hours at the Serpentine Galleries

- Marina Abramović: Advice to Young Artists Video by Louisiana Channel

- Marina Abramović & Ulay: Living Doors of the Museum Video by Louisiana Channel

- The Story of Marina Abramović and Ulay Video by Louisiana Channel

- 47-minute in-depth interview – Marina Abramović: Electricity Passing Through Video by Louisiana Channel

- Abramovic SKNY Sean Kelly Gallery

- Marina Abramović at Art:21

- Marina Abramović on Artnet

- Marina Abramovic Institute, Hudson, NY.

- Marina Abramović at the Lisson Gallery

- Royal Academy of Arts Marina Abramović

- 1946 births

- 20th-century women artists

- Art duos

- Artists from Belgrade

- Body art

- Academic staff of the École des Beaux-Arts

- Honorary members of the Royal Academy

- Living people

- Film people from Belgrade

- Recipients of the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art

- Serbian contemporary artists

- Serbian expatriates in the United States

- Serbian philanthropists

- Signalism

- Walking artists

- Endurance artists

- Yugoslav artists

- Serbian performance artists

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts

- Academic staff of the Berlin University of the Arts

- Serbian women artists

- Yugoslav expatriates in the Netherlands

- Serbian people of Montenegrin descent

- Serbian anti-war activists